INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

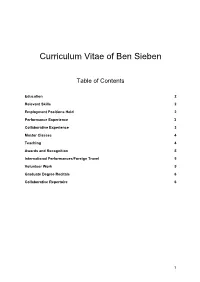

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben

Curriculum Vitae of Ben Sieben Table of Contents Education 2 Relevant Skills 2 Employment Positions Held 2 Performance Experience 3 Collaborative Experience 3 Master Classes 4 Teaching 4 Awards and Recognition 5 International Performances/Foreign Travel 5 Volunteer Work 5 Graduate Degree Recitals 6 Collaborative Repertoire 6 1 BEN SIEBEN [email protected] | 979-479-1197 | 61 San Jacinto St., Bay City, TX, 77414 Education Master of Music in Collaborative Piano 2017 University of Colorado Boulder Primary instructors: Margaret McDonald and Alexandra Nguyen Master of Music in Piano Performance 2012 University of Utah Primary instructor: Heather Conner Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance 2010 Houston Baptist University Primary instructor: Melissa Marse Relevant Skills 25 years of classical piano sight reading improvisation open-score reading transposition jazz and rock styles basso-continuo harpsichord music theory score arranging transcription by ear reading lead sheets keyboard/synthesizer proficiency Italian, German, French, and English diction fluent conversational Spanish Employment Positions Held Emerging Musical Artist-in-Residence, Penn State Altoona 2017 Vocal coach and accompanist for private voice students Graduate Assistant, University of Colorado Boulder 2015-2017 Collaborative pianist, pianist for instrumental students, vocal students, orchestra, opera, and opera scenes classes Choral Accompanist, Texas A&M University 2012-2015 Accompanist for Century Singers and Women’s Chorus Choral Accompanist, Brazos Valley Chorale -

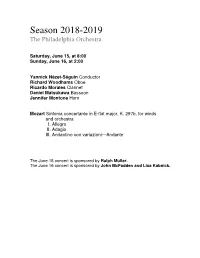

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

Khachaturian Nocturne from the Masquerade Piano Solo Sheet Music

Khachaturian Nocturne From The Masquerade Piano Solo Sheet Music Download khachaturian nocturne from the masquerade piano solo sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of khachaturian nocturne from the masquerade piano solo sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 7701 times and last read at 2021-09-27 00:51:22. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of khachaturian nocturne from the masquerade piano solo you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Masquerade Suite Aram Khachaturian Masquerade Suite Aram Khachaturian sheet music has been read 10264 times. Masquerade suite aram khachaturian arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 23:16:42. [ Read More ] Waltz From The Suite Masquerade By Aram Khachaturian For String Quartet Waltz From The Suite Masquerade By Aram Khachaturian For String Quartet sheet music has been read 6238 times. Waltz from the suite masquerade by aram khachaturian for string quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 20:02:58. [ Read More ] A Khachaturian Waltz From The Masquerade Brass Quintet Score And Parts A Khachaturian Waltz From The Masquerade Brass Quintet Score And Parts sheet music has been read 13960 times. A khachaturian waltz from the masquerade brass quintet score and parts arrangement is for Intermediate level. -

Choose Yourfavorite Three Concerts

CHOOSE YOUR FAVORITE THREE CONCERTS. You’ll Save 33% – That’s Up to $200 in Savings with Added Benefits Call 212-875-5656 or visit nyphil.org/CYO33 and use promo code CYO33. ** U.S. Premiere–New York Philharmonic Co-Commission with the London Philharmonic Orchestra *** World Premiere–New York Philharmonic Commission † Commissions made possible by The Marie-Josée Kravis Prize for New Music †New York City Premiere–New York Philharmonic Co-Commission Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 7:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 8:00pm 8:00pm unless otherwise noted unless otherwise noted Conductor Guest Artists Program Esa-Pekka Leila Josefowicz violin RAVEL Mother Goose Suite NOV Salonen Esa-Pekka SALONEN Violin Concerto NOV OCT OCT NOV conductor (New York Concert Premiere) 5 30 31 1 2 SIBELIUS Symphony No. 5 (11:00am) Bernard Miah Persson soprano J.S. BACH Cantata No. 51, Jauchzet Labadie Stephanie Blythe Gott in allen Landen! conductor mezzo-soprano HANDEL “Let the Bright Seraphim” Frédéric Antoun tenor from Samson Andrew Foster- MOZART Requiem NOV NOV NOV Williams bass 7 8 9 Matthew Muckey trumpet New York Choral Artists Joseph Flummerfelt director Alan Gilbert Liang Wang oboe R. STRAUSS Also sprach Zarathustra conductor Glenn Dicterow, violin NOV Christopher ROUSE Oboe Concerto NOV NOV NOV 15 (New York Premiere) 19 14 16 R. STRAUSS Don Juan (2:00pm) Glenn Dicterow, violin Alan Gilbert Paul Appleby tenor BRITTEN Serenade for Tenor, Horn, conductor Philip Myers horn and Strings Kate Royal soprano BRITTEN Spring Symphony Sasha Cooke mezzo-soprano NOV NOV NOV New York Choral Artists 21 22 23 Joseph Flummerfelt director Brooklyn Youth Chorus Dianne Berkun- Menaker director Alan Gilbert Paul Appleby tenor MOZART Symphony No. -

PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Clarinet Concerto in a Major, K

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 Mozart composed this concerto between the end of September and mid-November 1791, and it apparently was performed in Vienna shortly afterwards. The orchestra consists of two flutes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-nine minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was given at the Ravinia Festival on July 25, 1957, with Reginald Kell as soloist and Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra’s first subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on May 2, 1963, with Clark Brody as soloist and Walter Hendl conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on October 11 and 12, 1991, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra most recently performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 15, 2001, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Andrew Davis conducting. This concerto is the last important work Mozart finished before his death. He recorded it in his personal catalog without a date, right after The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito. The only later entry is the little Masonic Cantata, dated November 15, 1791. The Requiem, as we know, didn’t make it into the list. For decades the history of the Requiem was full of ambiguity, while that of the Clarinet Concerto seemed quite clear. But in recent years, as we learned more about the unfinished Requiem, questions about the concerto began to emerge. -

Myths, Legends, Fairy Tales and Folk Tales in Music ______

______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Sounds of Enchantment: Myths, Legends, Fairy Tales and Folk Tales in Music ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Gioacchino ROSSINI Overture from William Tell Felix MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream Sergei PROKOFIEV Waltz Coda and Midnight from Cinderella, Op. 87 David CROWE How Birds Came Into the World John WILLIAMS Raiders March from Raiders of the Lost Ark Piotr Ilyich TCHAIKOVSKY Scene from Swan Lake Modest MUSSORGSKY / arr. Ravel Baba Yaga and The Great Gate of Kiev from Pictures at an Exhibition HOW TO USE THIS STUDY GUIDE This guide is designed as a curriculum enhancement resource primarily for music teachers, but is also available for use by classroom teachers, parents, and students. The main intent is to aid instructors in their own lesson preparation, so most of the language and information is geared towards the adult, and not the student. It is not expected that all the information given will be used or that all activities are applicable to all settings. Teachers and/or parents can choose the elements that best meet the specific needs of their individual situations. Our hope is that the information will be useful, spark ideas, and make connections. TABLE OF CONTENTS Sounds of Enchantment Overview – Page 4 Program Notes – Page 7 ROSSINI | Overture from William Tell Page 8 MENDELSSOHN | Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream Page 10 PROKOFIEV | Waltz Coda and Midnight from Cinderella, Op. 87 Page 13 CROWE | How Birds Came Into the World Page 17 WILLIAMS | Raiders March from Raiders of the Lost Ark Page 20 TCHAIKOVSKY | Scene from Swan Lake Page 22 MUSSORGSKY | Baba Yaga and The Great Gate of Kiev from Pictures at an Exhibition Page 24 Activities — Page 27 Student Section— Page 39 CREDITS This guide was originally created for the 2008-2009 Charlotte Symphony Education Concerts by Susan Miville, Chris Stonnell, Anne Stewart, and Jane Orrell. -

A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music

1 Kristen Masada and Razvan Bunescu: A Segmental CRF Model for Chord Recognition in Symbolic Music A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music minished triads most frequently contain a diminished A chord is a group of notes that form a cohesive har- seventh interval (9 half steps), producing a fully di- monic unit to the listener when sounding simulta- minished seventh chord, or a minor seventh interval, neously (Aldwell et al., 2011). We design our sys- creating a half-diminished seventh chord. tem to handle the following types of chords: triads, augmented 6th chords, suspended chords, and power A.2 Augmented 6th Chords chords. An augmented 6th chord is a type of chromatic chord defined by an augmented sixth interval between the A.1 Triads lowest and highest notes of the chord (Aldwell et al., A triad is the prototypical instance of a chord. It is 2011). The three most common types of augmented based on a root note, which forms the lowest note of a 6th chords are Italian, German, and French sixth chord in standard position. A third and a fifth are then chords, as shown in Figure 8 in the key of A minor. built on top of this root to create a three-note chord. In- In a minor scale, Italian sixth chords can be seen as verted triads also exist, where the third or fifth instead iv chords with a sharpened root, in the first inversion. appears as the lowest note. The chord labels used in Thus, they can be created by stacking the sixth, first, our system do not distinguish among inversions of the and sharpened fourth scale degrees. -

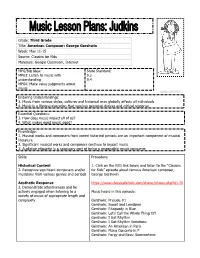

Grade: Third Grade Title: American Composer: George Gershwin Week: May 11-15 Source: Classics for Kids Materials: Google Classroom, Internet

Grade: Third Grade Title: American Composer: George Gershwin Week: May 11-15 Source: Classics for Kids Materials: Google Classroom, Internet MPG/Big Idea: State Standard: MPG3: Listen to music with 9.2 understanding 9.4 MPG4: Make value judgments about music Enduring Understandings: 3. Music from various styles, cultures and historical eras globally affects all individuals 4. Music is a lifelong avocation that requires personal choices and critical response Essential Questions: 3. How does music impact all of us? 4. What makes good music good? Knowledge: 1. Musical works and composers from varied historical periods are an important component of musical literature 3. Significant musical works and composers continue to impact music 3. Audience etiquette is a necessary part of being a responsible music consumer Skills: Procedure: Historical Context 1. Click on the RED link below and listen to the “Classics 2. Recognize significant composers and/or for Kids” episode about famous American composer, musicians from various genres and periods George Gershwin Aesthetic Response https://www.classicsforkids.com/shows/shows.php?id=70 3. Demonstrate attentiveness and be actively engaged when listening to a Music heard in this episode: variety of music of appropriate length and complexity Gershwin: Prelude #1 Gershwin: Sweet and Lowdown Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue Gershwin: Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off Gershwin: I Got Rhythm Gershwin: I Got Rhythm Variations Gershwin: An American in Paris Gershwin: Piano Concerto in F Gershwin: Porgy and Bess: Summertime 2. When finished complete the assignment on the Google Form below Assessment: Answer the multiple-choice questions by using the BLUE link below to open the Google form: https://forms.gle/VMryZf38P3rTPYL8A George Gershwin was born in a. -

With a Rich History Steeped in Tradition, the Courage to Stand Apart and An

With a rich history steeped in tradition, the courage to stand apart and an enduring joy of discovery, the Wiener Symphoniker are the beating heart of the metropolis of classical music, Vienna. For 120 years, the orchestra has shaped the special sound of its native city, forging a link between past, present and future like no other. In Andrés Orozco-Estrada - for several years now an adopted Viennese - the orchestra has found a Chief Conductor to lead this skilful ensemble forward from the 20-21 season onward, and at the same time revisit its musical roots. That the Wiener Symphoniker were formed in 1900 of all years is no coincidence. The fresh wind of Viennese Modernism swirled around this new orchestra, which confronted the challenges of the 20th century with confidence and vision. This initially included the assured command of the city's musical past: they were the first orchestra to present all of Beethoven's symphonies in the Austrian capital as one cycle. The humanist and forward-looking legacy of Beethoven and Viennese Romanticism seems tailor-made for the Symphoniker, who are justly leaders in this repertoire to this day. That pioneering spirit, however, is also evident in the fact that within a very short time the Wiener Symphoniker rose to become one of the most important European orchestras for the premiering of new works. They have given the world premieres of many milestones of music history, such as Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Franz Schmidt's The Book of the Seven Seals - concerts that opened a door onto completely new worlds of sound and made these accessible to the greater masses. -

Dec 21 to 27.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Dec. 21 - 27, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 12/21/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, Op. 3, No. 10 6:12 AM TRADITIONAL Gabriel's Message (Basque carol) 6:17 AM Francisco Javier Moreno Symphony 6:29 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Sonata No.4 6:42 AM Johann Christian Bach Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello 7:02 AM Various In dulci jubilo/Wexford Carol/N'ia gaire 7:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 7 7:30 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Trumpet and Violin 7:43 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Concerto 8:02 AM Henri Dumont Magnificat 8:15 AM Johann ChristophFriedrich Bach Oboe Sonata 8:33 AM Franz Krommer Concerto for 2 Clarinets 9:05 AM Joaquin Turina Sinfonia Sevillana 9:27 AM Philippe Gaubert Three Watercolors for Flute, Cello and 9:44 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Fantasia on Christmas Carols 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude & Fugue after Bach in d, 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 9 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 29 10:50 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude (Fantasy) and Fugue 11:01 AM Mily Balakirev Symphony No. 2 11:39 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Overture (suite) for 3 oboes, bsn, 2vns, 12:00 PM THE CHRISTMAS REVELS: IN CELEBRATION OF THE WINTER SOLSTICE 1:00 PM Richard Strauss Oboe Concerto 1:26 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 2:00 PM James Pierpont Jingle Bells 2:07 PM Julius Chajes Piano Trio 2:28 PM Francois Devienne Symphonie Concertante for flute, 2:50 PM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, "Il Riposo--Per Il Natale" 3:03 PM Zdenek Fibich Symphony No. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Year 11 Music Revision Guide

Year 11 Music Revision Guidance Name the musical instrument In the exam you will be asked to name different instruments that you can hear playing. If you do not play one of these instruments it can sometimes be quite difficult to pick out what each one sounds like. You will need to know what the different instruments of the orchestra sound like, what popular musical instruments sound like and what some world instruments sound like (sitar). It is worth you visiting www.dsokids.com or www.compositionlab.co.uk where you will be able to hear these instruments individually. Describing musical sounds For some questions in the exam you will need to describe what is happening in the music, in detail! If you are asked to comment on what is happening in the music you may need to describe what a particular instrument is doing, for example: ‘The left hand of the piano is playing ascending arpeggios’. The more detail you can provide, the better! Melodic movement You may be asked to describe what is happening in the melody of a song. Remember, this means the main tune. In popular music this is often the vocal line or in instrumental music it can be described as the instrument that has the main tune (the bit that you could whistle). It could move by STEP; this means it moves to the note next to it. It could move by LEAP; this means that the melody jumps from one note to another but misses some notes out in between. This could be a low note jumping to a high note or vice versa.