Empty Citizenship: Protesting Politics in the Era of Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management and Economy in Hartals: the Case of Bangladesh

Document generated on 09/28/2021 8:37 p.m. Journal of Comparative International Management Management and Economy in Hartals The Case of Bangladesh Khondaker Mizanur Rahman Volume 17, Number 1, September 2014 Article abstract Based on the secondary sources and interviews, this paper gives an account of URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcim17_1art03 hartal and similar political activities, examining the economic and social impacts of such activities on the economy of Bangladesh and the management of the See table of contents companies in that country. As hartal and associated activities are not well defined in literature, this study begins by giving a brief definition and description of those activities. The findings of the study suggest that these activities are Publisher(s) organized to ensure freedom of assembly, expression of opinion, and political rights by raising protests against certain government actions and policies. Management Futures However, in reality, and especially during the last two decades, much of these activities have been used as a vindictive movement against the political party in ISSN the helm of the regime. The study also found that hartal and similar activities have resulted in colossal economic losses of work, working hours, business 1481-0468 (print) management, industrial output, business capital, property, and human life, as 1718-0864 (digital) well as visible and non-visible social losses, such as human distress, loss of human life, uncertainly, chaos, hatred, disunity among people, and erosion of the Explore this journal national image. Finally, this study found that people engaged in economic activities dislike such political activities, considering them as unnecessary evils, and want political parties to work on creating alternative, peaceful action Cite this article programs. -

Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, Kerala – 686560

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY, KOTTAYAM, KERALA – 686560 DETAILS OF WORKS PERFORMED IN EACH SECTION OF THE UNIVERSITY Supervisory Officers Section Contact Sl. No. Name of Section Dealing works in the Section E-Mail ID Deputy Number Assistant Registrar Registrar ADMINISTRATION Service matters of Staff: 1. AD A I 0481-2733280 [email protected] JR/DR/AR/SO/Assistants Service Matters of: OA/Clerical Asst./Sto re Asst./Staff Nurse/Roneo Operator/Lab Techn 2. AD A III 0481-2733302 [email protected] (health centre)/Tele. Operator GO Endorsement, Part Time Sweeper engagement Service Matters – FC&D, Drivers, Engineers, Computer Programmers, Security Personal, Anti 3. AD A IV 0481-2733303 [email protected] Harassment Cell, Sanctioning of leave to SO & Above officers AR I (Admn) DR I (Admn) Pension: Bill preparation, Pension certificate 0481-2733239 0481-2733226 4. AD A VIII 0481-27733420 [email protected] issue, Income Tax matters of pensioners Pension Calculation, Pension Sanctioning, NLC [email protected] 5. AD A X Issuing, Family pension, VRS, Restoration of 0481-2333420 commuted portion of pensioners 6. AD A VI Medical Reimbursement 0481-2733305 [email protected] 7. Records Keeping University Records 0481-2733412 DR III All administrative matters related to Inter AR V (Admn) 8. AD A VII 0481-2733425 [email protected] (ADMN) University / Inter School Centres 0481-273 0481-273 3608 Service matters of VC, PVC, Registrar, FO, and [email protected] AR II (Admn.) DR II (Admn) 9. Ad A II 0481-2733281 CE. 0481-2733240 0481-2733227 1 Supervisory Officers Section Contact Sl. -

Preliminary Pages.Qxd

State Formation and Radical Democracy in India State Formation and Radical Democracy in India analyses one of the most important cases of developmental change in the twentieth century, namely, Kerala in southern India, and asks whether insurgency among the marginalized poor can use formal representative democracy to create better life chances. Going back to pre-independence, colonial India, Manali Desai takes a long historical view of Kerala and compares it with the state of West Bengal, which like Kerala has been ruled by leftists but has not experienced the same degree of success in raising equal access to welfare, literacy and basic subsistence. This comparison brings historical state legacies, as well as the role of left party formation and its mode of insertion in civil society to the fore, raising the question of what kinds of parties can effect the most substantive anti-poverty reforms within a vibrant democracy. This book offers a new, historically based explanation for Kerala’s post- independence political and economic direction, drawing on several comparative cases to formulate a substantive theory as to why Kerala has succeeded in spite of the widespread assumption that the Indian state has largely failed. Drawing conclusions that offer a divergence from the prevalent wisdoms in the field, this book will appeal to a wide audience of historians and political scientists, as well as non-governmental activists, policy-makers, and those interested in Asian politics and history. Manali Desai is Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Kent, UK. Asia’s Transformations Edited by Mark Selden Binghamton and Cornell Universities, USA The books in this series explore the political, social, economic and cultural consequences of Asia’s transformations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. -

2017 - 2018 Golden Jubilee Year Sree Narayana College Nattika

SREE NARAYANA COLLEGE NATTIKA, THRISSUR PIN- 680566 ESTD : 1967 Affiliated to the University of Calicut NAAC Reaccredited with B+ Grade DST-FIST Supported Institution Phone : 0487 - 2391246 Fax : 0487 - 2391246 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.sncollegenattika.org HANDBOOK & CALENDAR 2017 - 2018 GOLDEN JUBILEE YEAR SREE NARAYANA COLLEGE NATTIKA PmXn-t`Zw aX-tZz-j˛ taXp-an-√msX k¿∆cpw tkmZ-c-tXz\ hmgp∂ amXrIm-ÿm-\-am-WnXv {io\m-cm-bW Kpcp. Revision, Compilation and Editing : Smt. Babitha B. Printed & Published by: Dr. C. Anitha Sankar, Principal Sree Narayana College, Nattika, Thrissur, Kerala. 2 GOLDEN JUBILEE YEAR SREE NARAYANA COLLEGE NATTIKA CONTENTS 1. Daiva Dasakam 4 2. Profile 5 3. Programmes Offered 7 4. Management of the College 23 5. College Council 24 6. Faculty 25 7. Non Teaching Staff 36 8. College Byelaws 39 9. College Library 49 10. Scholarships and Endowments 51 11. Committees, Study Centres and Clubs 54 12. College Calendar 61 13. Forms of Applications 66 14. Colleges under S.N. Trusts 69 15. Important Telephone Numbers 70 16. Academic Calendar 71 3 GOLDEN JUBILEE YEAR SREE NARAYANA COLLEGE NATTIKA ssZh-Z-iIw ssZhta ImØpsImƒIßp ssIhn-Sm-Xn-ßp Rßsf \mhn-I≥ \o `hm-_v[n-s°m-cm-hn-h≥tXmWn \n≥]Zw Hs∂m-∂msbÆn-sb-Æn-sØm-s´Æpw s]mcp-sfm-Sp-ßn-bm¬ \n∂nSpw Zr°p-t]m-ep≈w \n∂n-e-kv]-µ-am-IWw A∂-h-kv{Xm-Zn-ap-´msX X∂p-c-£n®p Rßsf [\y-cm-°p∂ \osbm-∂p-Xs∂ R߃°p Xºp-cm≥ Bgnbpw Xncbpw Im‰pw Bghpw t]mse Rßfpw ambbpw \n≥ aln-abpw \obp-sa-∂p-≈n-em-IWw \obt√m krjvSnbpw {kjvSm-hm-bXpw krjvSn-Pm-ehpw \obt√m ssZh-ta, krjvSn-°p≈ kma-{Kn-bm-bXpw \obt√m ambbpw ambm-hnbpw ambm-hn-t\m-Z\pw \obt√m ambsb \o°n- kmbqPyw \¬Ip-am-cy\pw \o kXyw ⁄m\-am-\µw \o Xs∂ h¿Ø-am-\hpw `qXhpw `mhnbpw thd--t√mXpw samgn-bp-tam¿°n¬ \o AIhpw ]pdhpw Xnßpw aln-am-hm¿∂ \n≥]Zw ]pI-gvØp∂q Rß-fßv `K-hmt\ Pbn-°pI Pbn-°pI alm-tZh Zo\m-h-\-]-cm-bW Pbn-°pI NnZm-\µ Zbm-knt‘m Pbn-°p-I. -

Kerala – CPI-M – BJP – Communal Violence – Internal Relocation

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND34462 Country: India Date: 25 March 2009 Keywords: India – Kerala – CPI-M – BJP – Communal violence – Internal relocation This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide brief information on the nature of the CPI-M and the BJP as political parties and the relationship between the two in Kerala state. 2. Are there any reports of Muslim communities attacking Hindu communities in Kerala in the months which followed the 1992 demolition of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya? If so, do the reports mention whether the CPI-M supported or failed to prevent these Muslim attacks? Do any such reports specifically mention incidents in Kannur, Kerala? 3. With a view to addressing relocation issues: are there areas of India where the BJP hold power and where the CPI-M is relatively marginal? 4. Please provide any sources that substantiate the claim that fraudulent medical documents are readily available in India. RESPONSE 1. Please provide brief information on the nature of the CPI-M and the BJP as political parties and the relationship between the two in Kerala state. -

SREE NARAYANA COLLEGE, SIVAGIRI, VARKALA International Webinar Series: Lecture 1: 07.08.2020; Lecture 2 : 10.09.2020; Lecture 3: 11.09.2020

SREE NARAYANA COLLEGE, SIVAGIRI, VARKALA International Webinar Series: Lecture 1: 07.08.2020; Lecture 2 : 10.09.2020; Lecture 3: 11.09.2020 Webinar Report Sree Narayana College, Sivagiri, Varkala was founded in 1964 in memory of the great social reformer Sree Narayana Guru, who believed in “Liberation Through Education and Strength through Organisation”. The Post Graduate Department of Physics started functioning as a graduate department in 1967, three years after the inception of college in 1964 and the department was later upgraded to a Post Graduate Department in 1995. The International Webinar Series on Materials Science was jointly organized by the Post Graduate Department of Physics and IQAC, Sree Narayana College, Sivagiri, Varkala in association with kerala State Higher Education Council. This was the first in the International Webinar series organised by our college on 07.08.2020 . The purpose of organising this webinar series is to offer a common platform for discussing the recent developments in the field of Materials Science and to share their knowledge to enhance the capacity building. The upsurge of technology has revolutionized our lives and the outlook towards sustainable living, the ever increasing concern for maximising the output and minimising the waste has been a matter of discussion all over the world. Lecture 1: 07.08.2020 The session started with a silent prayer. Dr. Aranya S., Assistant Professor and HoD, Department of Physics, welcomed everyone to the seminar session. The inaugural address was delivered by Dr. K. C. Preetha, Principal. Dr. R Raveendran (UGC Emeritus Professor, Special Officer Sree Narayana Trusts and Former Principal of Sree Narayana College, Sivagiri, Varkala) Sri. -

Aided B.Ed Colleges Under Calicut University.Pdf

GO TO INDEX CATERGORY WISE LIST OF COLLEGES GO TO INDEX CATERGORY WISE LIST OF COLLEGES & INTAKE OF SEATS UPTO 02.11.2012 Sl.No Category Government Aided Unaided Total 2011-2012 2012-13 Total intake 1 Arts & Science 19 45 106 170 38895 1891 4 0786 2 Fine Arts 1 1 4 0 4 0 3 Engineering 3 1 32 36 13623 114 0 14 763 4 B.Arch 4 4 80 80 160 5 MBA/Management 8 8 660 60 720 6 Medical 2 5 7 1063 1063 7 Homeo 1 1 120 120 8 Ayurveda 2 4 6 312 312 9 Dental 1 6 7 376 376 10 Pharmacy 1 8 9 590 590 11 Paramedical Science 4 4 126 126 12 Nursing 2 19 21 1275 1275 13Law College 2 1 3 385 220 605 14 Physical Education 1 1 2 114 114 15 Training Colleges 2 2 59 63 7295 7295 16 Arabic Colleges 9 19 28 1066 180 124 6 Total 35 59 276 370 66020 3571 69591 GO TO INDEX INDEX I.THRISSUR 1.Arts & Science Colleges 1.1Government Colleges 1.2Aided Colleges 1.3Unaided Colleges 2.Fine Arts 2.1Government Colleges 3.Engineering Colleges 3.1Government Colleges 3.2Unaided Colleges 4.B.ARCH 4.1Unaided Colleges 5.MBA/Management Colleges 5.1Unaided Colleges 6.Medical Colleges 6.1Government Colleges 6.2Unaided Colleges 6.aDental 6.a.1Unaided Colleges 6.bAyurveda 6.b.1Aided Colleges 7.Pharmacy Colleges 7.1Unaided Colleges 8.Nursing Colleges 8.1Government Colleges 8.2Unaided Colleges 9.Law Colleges 9.1Government Colleges 10.Physical Education 10.1Unaided Colleges 11.Training Colleges GO TO INDEX 11.1Government Colleges 11.2Unaided Colleges 12.Arabic Colleges 12.1Unaided Colleges II.PALAKKAD 1. -

Ticfkаўmа Hnzym`Ymkhip¸V

tIcfkÀ¡mÀ hnZym`ymkhIp¸v 2021 amÀ¨nse Fkv.Fkv.FÂ.kn än.F¨v.Fkv.FÂ.kn. Fkv.Fkv.FÂ.kn (F¨v.sF) än.F¨v.Fkv.FÂ.kn. (F¨v.sF) F.F¨v.Fkv.FÂ.kn ]co£IÄ dnt¸mÀ«v, dnkÄ«v A]{KY\w, s]mXphnhc§Ä ]co£m`h³, tIcfw Xncph\´]pcw www.keralapareekshabhavan.in Table of Contents REPORT........................................................................................................................................1 SSLC EXAMINATION - MARCH 2021..................................................................................10 RESULT AT A GLANCE.....................................................................................................10 . SCHOOL GOING CANDIDATES....................................……………………….. …. 10 . PRIVATE NEW & OLD SCHEME..................................................................................11 RESULT ANALYSIS – 2013 - 2021.....................................................................................12 RESULT AT A GLANCE (IN MALAYALAM).................................................................13 . SCHOOL GOING CANDIDATES..................................................................................13 . PRIVATE NEW & OLD CANDIDATES.........................................................................14 . SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE EXAMINATION.........................................................15 REVENUE DISTRICT WISE DETAILS OF CANDIDATES OBTAINED A+ FOR ALL SUBJECTS..18 ABSTRACT OF RESULT...................................................................................................19 -

Issue Paper BANGLADESH POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS DECEMBER 1996-APRIL 1998 May 1998

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/POLITICAL... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper BANGLADESH POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS DECEMBER 1996-APRIL 1998 May 1998 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents MAP GLOSSARY 1. INTRODUCTION 2. KEY POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS 2.1 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 2.2 Ganges Water Sharing Agreement 2.3 General Strikes and Restrictions on Rallies 2.4 Elections 2.5 Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) Peace Treaty 3. LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS 3.1 Law Reform Commission 3.2 Judicial Reform 1 of 27 9/16/2013 3:57 PM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/POLITICAL... 3.3 National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) 3.4 Special Powers Act (SPA) 4. OPPOSITION PARTIES 4.1 Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) 4.2 Jatiya Party (JP) 4.3 Jamaat-e-Islami (Jamaat) 5. FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS REFERENCES MAP See original. Source: UNHCR Refworld -

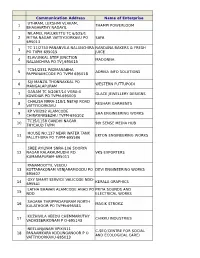

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

Sumi Project

1 CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................ 3-11 Chapter 1 Melting Jati Frontiers ................................................................ 12-25 Chapter 2 Enlightenment in Travancore ................................................... 26-45 Chapter 3 Emergence of Vernacular Press; A Motive Force to Social Changes .......................................... 46-61 Chapter 4 Role of Missionaries and the Growth of Western Education...................................................................... 62-71 Chapter 5 A Comparative Study of the Social Condions of the Kerala in the 19th Century with the Present Scenerio...................... 72-83 Conclusion ............................................................................................ 84-87 Bibliography .......................................................................................88-104 Glossary ............................................................................................105-106 2 3 THE SOCIAL CONDITIONS OF KERALA IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO TRAVANCORE PRINCELY STATE Introduction In the 19th century Kerala was not always what it is today. Kerala society was not based on the priciples of social freedom and equality. Kerala witnessed a cultural and ideological struggle against the hegemony of Brahmins. This struggle was due to structural changes in the society and the consequent emergence of a new class, the educated middle class .Although the upper caste -

BANGLADESH: from AUTOCRACY to DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values)

BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 Professor PARK, Hun-Joo (David) ABSTRACT BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY By Golam Shafiuddin The political history of independent Bangladesh is the history of authoritarianism, argument of force, seizure of power, rigged elections, and legitimacy crisis. It is also a history of sustained campaigns for democracy that claimed hundreds of lives. Extremely repressive measures taken by the authoritarian rulers could seldom suppress, or even weaken, the movement for the restoration of constitutionalism. At times the means adopted by the rulers to split the opposition, create a democratic facade, and confuse the people seemingly served the rulers’ purpose. But these definitely caused disenchantment among the politically conscious people and strengthened their commitment to resistance. The main problems of Bangladesh are now the lack of national consensus, violence in the politics, hartal (strike) culture, crimes sponsored with political ends etc. which contribute to the negation of democracy. Besides, abject poverty and illiteracy also does not make it easy for the democracy to flourish. After the creation of non-partisan caretaker government, the chief responsibility of the said government was only to run the routine administration and take all necessary measures to hold free and fair parliamentary elections.