Fringe Maths Through It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A MATHEMATICIAN's SURVIVAL GUIDE 1. an Algebra Teacher I

A MATHEMATICIAN’S SURVIVAL GUIDE PETER G. CASAZZA 1. An Algebra Teacher I could Understand Emmy award-winning journalist and bestselling author Cokie Roberts once said: As long as algebra is taught in school, there will be prayer in school. 1.1. An Object of Pride. Mathematician’s relationship with the general public most closely resembles “bipolar” disorder - at the same time they admire us and hate us. Almost everyone has had at least one bad experience with mathematics during some part of their education. Get into any taxi and tell the driver you are a mathematician and the response is predictable. First, there is silence while the driver relives his greatest nightmare - taking algebra. Next, you will hear the immortal words: “I was never any good at mathematics.” My response is: “I was never any good at being a taxi driver so I went into mathematics.” You can learn a lot from taxi drivers if you just don’t tell them you are a mathematician. Why get started on the wrong foot? The mathematician David Mumford put it: “I am accustomed, as a professional mathematician, to living in a sort of vacuum, surrounded by people who declare with an odd sort of pride that they are mathematically illiterate.” 1.2. A Balancing Act. The other most common response we get from the public is: “I can’t even balance my checkbook.” This reflects the fact that the public thinks that mathematics is basically just adding numbers. They have no idea what we really do. Because of the textbooks they studied, they think that all needed mathematics has already been discovered. -

MY UNFORGETTABLE EARLY YEARS at the INSTITUTE Enstitüde Unutulmaz Erken Yıllarım

MY UNFORGETTABLE EARLY YEARS AT THE INSTITUTE Enstitüde Unutulmaz Erken Yıllarım Dinakar Ramakrishnan `And what was it like,’ I asked him, `meeting Eliot?’ `When he looked at you,’ he said, `it was like standing on a quay, watching the prow of the Queen Mary come towards you, very slowly.’ – from `Stern’ by Seamus Heaney in memory of Ted Hughes, about the time he met T.S.Eliot It was a fortunate stroke of serendipity for me to have been at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, twice during the nineteen eighties, first as a Post-doctoral member in 1982-83, and later as a Sloan Fellow in the Fall of 1986. I had the privilege of getting to know Robert Langlands at that time, and, needless to say, he has had a larger than life influence on me. It wasn’t like two ships passing in the night, but more like a rowboat feeling the waves of an oncoming ship. Langlands and I did not have many conversations, but each time we did, he would make a Zen like remark which took me a long time, at times months (or even years), to comprehend. Once or twice it even looked like he was commenting not on the question I posed, but on a tangential one; however, after much reflection, it became apparent that what he had said had an interesting bearing on what I had been wondering about, and it always provided a new take, at least to me, on the matter. Most importantly, to a beginner in the field like I was then, he was generous to a fault, always willing, whenever asked, to explain the subtle aspects of his own work. -

June 2014 Society Meetings Society and Events SHEPHARD PRIZE: NEW PRIZE Meetings for MATHEMATICS 2014 and Events Following a Very Generous Tions Open in Late 2014

LONDONLONDON MATHEMATICALMATHEMATICAL SOCIETYSOCIETY NEWSLETTER No. 437 June 2014 Society Meetings Society and Events SHEPHARD PRIZE: NEW PRIZE Meetings FOR MATHEMATICS 2014 and Events Following a very generous tions open in late 2014. The prize Monday 16 June donation made by Professor may be awarded to either a single Midlands Regional Meeting, Loughborough Geoffrey Shephard, the London winner or jointly to collaborators. page 11 Mathematical Society will, in 2015, The mathematical contribution Friday 4 July introduce a new prize. The prize, to which an award will be made Graduate Student to be known as the Shephard must be published, though there Meeting, Prize will be awarded bienni- is no requirement that the pub- London ally. The award will be made to lication be in an LMS-published page 8 a mathematician (or mathemati- journal. Friday 4 July cians) based in the UK in recog- Professor Shephard himself is 1 Society Meeting nition of a specific contribution Professor of Mathematics at the Hardy Lecture to mathematics with a strong University of East Anglia whose London intuitive component which can be main fields of interest are in page 9 explained to those with little or convex geometry and tessella- Wednesday 9 July no knowledge of university math- tions. Professor Shephard is one LMS Popular Lectures ematics, though the work itself of the longest-standing members London may involve more advanced ideas. of the LMS, having given more page 17 The Society now actively en- than sixty years of membership. Tuesday 19 August courages members to consider The Society wishes to place on LMS Meeting and Reception nominees who could be put record its thanks for his support ICM 2014, Seoul forward for the award of a in the establishment of the new page 11 Shephard Prize when nomina- prize. -

How Significant an Influence Is Urban Form on City Energy Consumption for Housing and Transport?

How significant an influence is urban form on city energy consumption for housing and transport? Authored by: Dr Alan Perkins South Australian Department of Transport and Urban Planning and University of South Australia [email protected] How significant an influence is urban form on city energy consumption for housing & transport? Perkins URBAN FORM AND THE SUSTAINABILITY OF CITIES The ecological sustainability of cities can be measured, at the physical level, by the total flow of energy, water, food, mineral and other resources through the urban system, the ecological impacts involved in the generation of those resources, the manner in which they are used, and the manner in which the outputs are treated. The gap between the current unsustainable city and the ideal of the sustainable city has been described in the following way (Haughton, 1997). Existing cities are characterised by: The Sustainable city would be A high degree of external dependence, characterised by: extensive externalisation of Intensive internalisation of economic environmental costs, open systems, and environmental activities, circular linear metabolism and ‘buying-in’ metabolism, bioregionalism and additional carrying capacity. urban autarky. Urban forms are required therefore which will be best suited to the conception of the more self-sustaining, less resource hungry and waste profligate city. As cities seek to make their energy, water, biological and materials sub-systems more sustainable, the degree to which the intensification of urban development is supportive of these aims will become clearer. Nevertheless, many who have sought to portray what constitutes sustainable urban form from this broader perspective have included intensification, both urban and regional, as a key element (Berg et al, 1990; Register et al, 1990; Owens, 1994; Trainer, 1995; Breheny & Rookwood, 1996; Newman & Kenworthy, 1999; Barton & Tsourou, 2000). -

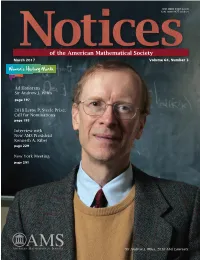

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

Robert P. Langlands Receives the Abel Prize

Robert P. Langlands receives the Abel Prize The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters has decided to award the Abel Prize for 2018 to Robert P. Langlands of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, USA “for his visionary program connecting representation theory to number theory.” Robert P. Langlands has been awarded the Abel Prize project in modern mathematics has as wide a scope, has for his work dating back to January 1967. He was then produced so many deep results, and has so many people a 30-year-old associate professor at Princeton, working working on it. Its depth and breadth have grown and during the Christmas break. He wrote a 17-page letter the Langlands program is now frequently described as a to the great French mathematician André Weil, aged 60, grand unified theory of mathematics. outlining some of his new mathematical insights. The President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and “If you are willing to read it as pure speculation I would Letters, Ole M. Sejersted, announced the winner of the appreciate that,” he wrote. “If not – I am sure you have a 2018 Abel Prize at the Academy in Oslo today, 20 March. waste basket handy.” Biography Fortunately, the letter did not end up in a waste basket. His letter introduced a theory that created a completely Robert P. Langlands was born in New Westminster, new way of thinking about mathematics: it suggested British Columbia, in 1936. He graduated from the deep links between two areas, number theory and University of British Columbia with an undergraduate harmonic analysis, which had previously been considered degree in 1957 and an MSc in 1958, and from Yale as unrelated. -

JPBM Communications Award Is Given to He Takes a Particular Interest in Problems That Lie Ian Stewart of the University of Warwick

comm-jpbm.qxp 3/5/99 3:49 PM Page 568 JPBM Awards Presented in San Antonio The Joint Policy Board for Mathematics (JPBM) The sheer volume of this work is staggering, but Communications Award was established in 1988 the quality is spectacular as well. With clarity and to reward and encourage journalists and other humor, Ian Stewart explains everything from num- communicators who, on a sustained basis, bring ber theory to fractals, from Euclidean geometry to accurate mathematical information to nonmathe- fluid dynamics, from game theory to foundations. matical audiences. Any person is eligible as long He conveys both the beauty and the utility of math- as that person’s work communicates primarily ematics in a way seldom achieved by a single au- with nonmathematical audiences. The lifetime thor, and he does so with charm and eloquence. award recognizes a significant contribution or ac- cumulated contributions to public understanding Biographical Sketch of mathematics. Ian Stewart was born in 1945, did his undergrad- At the Joint Mathematics Meetings in San An- uate degree at Cambridge, and his Ph.D. at Warwick. tonio in January 1999, the 1999 JPBM Communi- He is now a professor at Warwick University and cations Award was presented to IAN STEWART. Below director of the Mathematics Awareness Centre at is the award citation, a biographical sketch, and Warwick. He has held visiting positions in Ger- Stewart’s response upon receiving the award. This many, New Zealand, Connecticut, and Texas. He has is followed by information about a JPBM Special published over 120 papers. His present field is Communications Award presented to JOHN LYNCH the effects of symmetry on nonlinear dynamics, and SIMON SINGH. -

Response of a Nonlinear String to Random Loading1

discussion the barreling of the specimen were not large enough to be noticea- Since ble. The authors believe the effects of lateral inertia are small and 77" ^ DL much less serious than the end conditions. Referring again to ™ = g = Wo Fig. 4, the 1.5, 4.5, 6.5, and 7.5 fringes are nearly uniformly dis- tributed over the width of the specimen. The other fringes are and not as well distributed, but it is believed that the conditions at DL the ends of the specimen produced the irregularities rather than 7U72 = VV^ tr,2 = =-, lateral inertia effects. f~1 3ft 7'„ + AT) If the material were perfectly elastic and if one neglected lateral one has inertia effects, the fringes would build up as a consequence of wave propagation and reflection. Thus a difference in the fringe t/7W = (i + at/To)-> = (i + ffff./v)-1 (5) order over the length of the specimen woidd always exist. Inspec- tion of Fig. 4 shows this wave-propagation effect for the first which is Caughey's result for aai.^N small, which it must be for 6 frames as the one-half fringe propagates down the specimen the analysis to be consistent. It is obvious that the new linear Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/appliedmechanics/article-pdf/27/2/369/5443489/370_1.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 and reflects from the right-hand pendulum. However, from system with tension To + AT will satisfy equipartition. frame 7 on there is little evidence of wave propagation and the The work just referred to does not use equation (1) but rather fringe order at both ends of the specimen is equal. -

Commodity and Energy Markets Conference at Oxford University

Commodity and Energy Markets Conference Annual Meeting 2017 th th 14 - 15 June Page | 1 Commodity and Energy Markets Conference Contents Welcome 3 Essential Information 4 Bird’s-eye view of programme 6 Detailed programme 8 Venue maps 26 Mezzanine level of Andrew Wiles Building 27 Local Information 28 List of Participants 29 Keynote Speakers 33 Academic journals: special issues 34 Sponsors 35 Page | 2 Welcome On behalf of the Mathematical Institute, it is our great pleasure to welcome you to the University of Oxford for the Commodity and Energy Markets annual conference (2017). The Commodity and Energy Markets annual conference 2017 is the latest in a long standing series of meetings. Our first workshop was held in London in 2004, and after that we expanded the scope and held yearly conferences in different locations across Europe. Nowadays, the Commodity and Energy Markets conference is the benchmark meeting for academics who work in this area. This year’s event covers a wide range of topics in commodities and energy. We highlight three keynote talks. Prof Hendrik Bessembinder (Arizona State University) will talk on “Measuring returns to those who invest in energy through futures”, and Prof Sebastian Jaimungal (University of Toronto) will talk about “Stochastic Control in Commodity & Energy Markets: Model Uncertainty, Algorithmic Trading, and Future Directions”. Moreover, Tony Cocker, E.ON’s Chief Executive Officer, will share his views and insights into the role of mathematical modelling in the energy industry. In addition to the over 100 talks, a panel of academics and professional experts will discuss “The future of energy trading in the UK and Europe: a single energy market?” The roundtable is sponsored by the Italian Association of Energy Suppliers and Traders (AIGET) and European Energy Retailers (EER). -

Math Spans All Dimensions

March 2000 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Math Spans All Dimensions April 2000 is Math Awareness Month Interactive version of the complete poster is available at: http://mam2000.mathforum.com/ FOCUS March 2000 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January. February. March. April. May/June. August/September. FOCUS October. November. and December. a Editor: Fernando Gouvea. Colby College; March 2000 [email protected] Managing Editor: Carol Baxter. MAA Volume 20. Number 3 [email protected] Senior Writer: Harry Waldman. MAA In This Issue [email protected] Please address advertising inquiries to: 3 "Math Spans All Dimensions" During April Math Awareness Carol Baxter. MAA; [email protected] Month President: Thomas Banchoff. Brown University 3 Felix Browder Named Recipient of National Medal of Science First Vice-President: Barbara Osofsky. By Don Albers Second Vice-President: Frank Morgan. Secretary: Martha Siegel. Treasurer: Gerald 4 Updating the NCTM Standards J. Porter By Kenneth A. Ross Executive Director: Tina Straley 5 A Different Pencil Associate Executive Director and Direc Moving Our Focus from Teachers to Students tor of Publications and Electronic Services: Donald J. Albers By Ed Dubinsky FOCUS Editorial Board: Gerald 6 Mathematics Across the Curriculum at Dartmouth Alexanderson; Donna Beers; J. Kevin By Dorothy I. Wallace Colligan; Ed Dubinsky; Bill Hawkins; Dan Kalman; Maeve McCarthy; Peter Renz; Annie 7 ARUME is the First SIGMAA Selden; Jon Scott; Ravi Vakil. Letters to the editor should be addressed to 8 Read This! Fernando Gouvea. Colby College. Dept. of Mathematics. Waterville. ME 04901. 8 Raoul Bott and Jean-Pierre Serre Share the Wolf Prize Subscription and membership questions 10 Call For Papers should be directed to the MAA Customer Thirteenth Annual MAA Undergraduate Student Paper Sessions Service Center. -

Andrew Wiles and Fermat's Last Theorem

Andrew Wiles and Fermat's Last Theorem Ton Yeh A great figure in modern mathematics Sir Andrew Wiles is renowned throughout the world for having cracked the problem first posed by Fermat in 1637: the non-existence of positive integer solutions to an + bn = cn for n ≥ 3. Wiles' famous journey towards his proof { the surprising connection with elliptic curves, the apparent success, the discovery of an error, the despondency, and then the flash of inspiration which saved the day { is known to layman and professional mathematician alike. Therefore, the fact that Sir Andrew spent his undergraduate years at Merton College is a great honour for us. In this article we discuss simple number-theoretic ideas relating to Fermat's Last Theorem, which may be of interest to current or prospective students, or indeed to members of the public. Easier aspects of Fermat's Last Theorem It goes without saying that the non-expert will have a tough time getting to grips with Andrew Wiles' proof. What follows, therefore, is a sketch of much simpler and indeed more classical ideas related to Fermat's Last Theorem. As a regrettable consequence, things like algebraic topology, elliptic curves, modular functions and so on have to be omitted. As compensation, the student or keen amateur will gain accessible insight from this section; he will also appreciate the shortcomings of these classical approaches and be motivated to prepare himself for more advanced perspectives. Our aim is to determine what can be said about the solutions to an + bn = cn for positive integers a; b; c. -

Fringe Season 1 Transcripts

PROLOGUE Flight 627 - A Contagious Event (Glatterflug Airlines Flight 627 is enroute from Hamburg, Germany to Boston, Massachusetts) ANNOUNCEMENT: ... ist eingeschaltet. Befestigen sie bitte ihre Sicherheitsgürtel. ANNOUNCEMENT: The Captain has turned on the fasten seat-belts sign. Please make sure your seatbelts are securely fastened. GERMAN WOMAN: Ich möchte sehen wie der Film weitergeht. (I would like to see the film continue) MAN FROM DENVER: I don't speak German. I'm from Denver. GERMAN WOMAN: Dies ist mein erster Flug. (this is my first flight) MAN FROM DENVER: I'm from Denver. ANNOUNCEMENT: Wir durchfliegen jetzt starke Turbulenzen. Nehmen sie bitte ihre Plätze ein. (we are flying through strong turbulence. please return to your seats) INDIAN MAN: Hey, friend. It's just an electrical storm. MORGAN STEIG: I understand. INDIAN MAN: Here. Gum? MORGAN STEIG: No, thank you. FLIGHT ATTENDANT: Mein Herr, sie müssen sich hinsetzen! (sir, you must sit down) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Entschuldigen sie bitte! Gehen sie zu ihrem Sitz zurück! [please, go back to your seat!] FLIGHT ATTENDANT: (on phone) Kapitän! Wir haben eine Notsituation! (Captain, we have a difficult situation!) PILOT: ... gibt eine Not-... (... if necessary...) Sprechen sie mit mir! (talk to me) Was zum Teufel passiert! (what the hell is going on?) Beruhigen ... (...calm down...) Warum antworten sie mir nicht! (why don't you answer me?) Reden sie mit mir! (talk to me) ACT I Turnpike Motel - A Romantic Interlude OLIVIA: Oh my god! JOHN: What? OLIVIA: This bed is loud. JOHN: You think? OLIVIA: We can't keep doing this.