At Once, the Word 'Prolific' Seems Fittingly Appropriate, Yet Grossly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Theater ART HOUSE

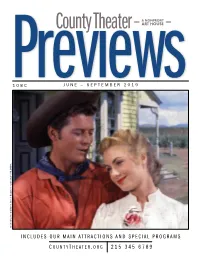

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

Film Essay for "7Th Heaven"

7th Heaven By Aubrey Solomon In the years between 1926 and 1928, Hollywood ex- perienced a maturation which blended art and indus- try to a new level of cinema. Influenced heavily by the experiments of foreign talents, largely German, new concepts of cinematography, lighting, set de- sign, and special effects known as “trick shots,” per- meated American film-making methods. The somber and sometimes morbid themes of German cinema also seeped into their films, often to the chagrin of American exhibitors who preferred their own exuber- ant optimism and happy endings. “7th Heaven” characterizes a perfect blend of opti- mistic romantic fantasy and German influenced pro- duction design. It also became one of the most pop- ular films of the late silent era. Its opening title card set the tone: “For those who will climb it, there is a ladder leading from the depths to the heights - from the sewer to the stars - the ladder of Courage.” Based on a hugely successful play by Austin Strong which ran at the Booth Theatre on Broadway from October 30, 1922, to May 21,1924 for a total of 685 performances, it portrayed the travails of young lov- An advertisement from a June 1927 edition of Motion ers who meet amidst the sordid gutters of pre-World Picture News. Courtesy Media History Digital Library. War I Paris. Happy-go-lucky street cleaner Chico saves waifish, homeless, Diane, a runaway from her abusive sister. Against Chico’s initial resistance, he Fox Films vice-president and general manager falls in love with Diane only to end up going to war Winfield Sheehan acknowledged audiences were and being declared dead in battle. -

The State of Things to Come

26 TEE$IAOE The state of things to come A word frequently associated with Rodgers and Hammerstein productions is 'Iavish, but for director Thom Southerland, his adaption of the film State Fair is based on telling the story in an intimate fringe setting. Jo Caird finds out more fter the exLrav aganza that telling a story with an accompani- was The King and I at the ment behind them." Royal Albert Hall, you'd Southerlandcontrasts his approach be forgiven for thinking to that championedby the director of of Rodgers and Hammerstein shows the recent Royal Albert Hall produc- as purely big budget affairs. But tion of The King and I. director Thom Southerlandwould "Jeremy Samswrote in the pro- disagree. Following small-scale gramme notesall abouthow people productions of HMS Pinafore, Annie love Rodgers and Hammerstein Get Your Gun and The Mikado, he becauseof the spectacle,the gran- has chosenEarl's Court'stiny deur of the music and huge lavish cos- Finborough Theatre as the venuefor tumes and I couldn't disagree more," the European premiere of State Fair, he says."People love the music and one of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Iovethe story and want to seeit in a least known works. fresh way." The musical is unusual for its time becauseit began life not as a stage showbut in the guise of a very successful1945 movie musical,which was then remade in 1962.It was only in the early nineties when amateur groups in the United States began petitioning the Rodgers and Ham- merstein estate for the releaseof further material that the film was adaptedfor the stage. -

Ferenc Molnar

L I L I O M A LEGEND IN SEVEN SCENES BY FERENC MOLNAR EDITED AND ADAPTED BY MARK JACKSON FROM AN ENGLISH TEXT BY BENJAMIN F. GLAZER v2.5 This adaptation of Liliom Copyright © 2014 Mark Jackson All rights strictly reserved. For all inquiries regarding production, publication, or any other public or private use of this play in part or in whole, please contact: Mark Jackson email: [email protected] www.markjackson-theatermaker.com CAST OF CHARACTERS (4w;4m) Marie / Stenographer Julie / Louise Mrs Muskat Liliom Policeman / The Guard Mrs Hollunder / The Magistrate Ficsur / A Poorly Dressed Man Wolf Beifeld / Linzman / Carpenter / A Richly Dressed Man SCENES (done minimally and expressively) FIRST SCENE — A lonely place in the park. SECOND SCENE — Mrs. Hollunder’s photographic studio. THIRD SCENE — Same as scene two. FOURTH SCENE — A railroad embankment outside the city. FIFTH SCENE — Same as scene two SIXTH SCENE — A courtroom in the beyond. SEVENTH SCENE — Julie’s garden, sixteen years later. A NOTE (on time & place) The current draft retains Molnar’s original 1909 Budapest setting. With minimal adjustments the play could easily be reset in early twentieth century America. Though I wonder whether certain of the social attitudes—toward soldiers, for example— would transfer neatly, certainly an American setting could embody Molnar’s complex critique of gender, class, and racial tensions. That said, retaining Molnar’s original setting perhaps now adds to his intention to fashion an expressionist theatrical legend, while still allowing for the strikingly contemporary themes that prompted me to write this adaptation—among them how Liliom struggles and fails to change in the face of economic and social flux; that women run the businesses, Heaven included; and Julie’s independent, confidently anti-conventional point of view. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

Hollywood Movie Stars California History Section Display

CALIFORNIA STATE LIBRARY NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2016 HOLLYWOOD MOVIE STARS CALIFORNIA HISTORY SECTION DISPLAY VISIT OUR CURRENT DISPLAY: MINING IN CALIFORNIA California History Section 900 N Street Room 200 9:30-4 Monday-Friday INTRODUCTION California has been a moviemaking powerhouse for over a century now! Get star- struck, and relive the glory days of yesteryear’s actors through our carefully curated selection of images, ephemera and books. If you want more infor- mation about our movie history resources, you can find them in the fol- lowing places: California State Library Catalog: Subject Searches: Motion picture actors and actresses California motion picture* Hollywood history California Information File II: Subject Searches: Motion picture actors and actresses California Motion picture* Hollywood history California Information File (In-house use): Subject Searches: Moving Pictures Counties: Los Angeles: Hollywood Drama: Actor Names California Image File (In-house use): Subject searches: Portraits: Actor Names Motion Pictures Contacting us: Web-form: Ask us a Question Email: [email protected] Enjoy our display! VISUALS Hoover, Art Company. 192AD. [Lena Basquette] (7 Views). Silent Movie Scene. 192AD. Hartsook, Photo. 192AD. Mary Pickford. VISUALS Blake, Orville T. 1929. Grauamaus [Sic] Chinese, Hollywood, CA. Graphic. Arthur Wenzel at Theater in Oakland. 1916. Graphic. Hoover, Art Company. 192AD. [Alice Terry] (2 Views). A Cecil B. DeMille Production: Fredric March in “The Buccaneer.” 1937. Graphic. VISUALS Farrell Collection. 1916. Mary Pickford in Hulda from Holland. Graphic. T&D. N.D. [Actor]. Graphic. Dobbins Collection. N.D. [Actress]. Graphic. VISUALS Portraits. N.D. Graphic. [Actors]. 1916. Graphic. Garrick Theater (Philadelphia, Penn.). c1913. [Advertisement]. Philadelphia: Garrick Theater. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

ARSC Journal

TOSCANINI LIVE BEETHOVEN: Missa Solemnis in D, Op. 123. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Alexander Kipnis, bass; Westminster Choir; VERDI: Missa da Requiem. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Nicola Moscona, bass; Westminster Choir, NBC Symphony Orchestra, Arturo Toscanini, cond. Melodram MEL 006 (3). (Three Discs). (Mono). BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125. Vina Bovy, soprano; Kerstin Thorborg, contralto; Jan Peerce, tenor; Ezio Pinza, bass; Schola Cantorum; Arturo Toscanini Recordings Association ATRA 3007. (Mono). (Distributed by Discocorp). BRAHMS: Symphonies: No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; No. 2 in D, Op. 73; No. 3 in F, Op. 90; No. 4 in E Minor, Op. 98; Tragic Overture, Op. 81; Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56A. Philharmonia Orchestra. Cetra Documents. Documents DOC 52. (Four Discs). (Mono). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2 in B Flat, Op. 83. Serenade No. 1 in D, Op. 11: First movement only; Vladimir Horowitz, piano (in the Concerto); Melodram MEL 229 (Two Discs). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68. MOZART: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550. TCHAIKOVSKY: Romeo and Juliet (Overture-Fantasy). WAGNER: Lohengrin Prelude to Act I. WEBER: Euryanthe Overture. Giuseppe Di Stefano Presenta GDS 5001 (Two Discs). (Mono). MOZART: Symphony No. 35 in D, K. 385 ("Haffner") Rehearsal. Relief 831 (Mono). TOSCANINI IN CONCERT: Dell 'Arte DA 9016 (Mono). Bizet: Carmen Suite. Catalani: La Wally: Prelude; Lorelei: Dance of the Water ~· H~rold: Zampa Overture. -

Scottsville Sun, 03 April 1952

• , " _FPUR I ~~=- '~~T~H~E~SC~O~'~I"l"SVILLE~U_}' THURSDAY; APRIL 3, 1952 AN The Scottsville Sun \ To The Editor. lup my war m~o.rial Highway and put this store I.?"r .what hav~ Y~'~~~~h~--:here ~e' attended the ])j THE NEIGHBORING COMM . 'illy Fluvanna country. back f,ar enougn JD the begmnrngiillonthly meeting a,f the Women's MARi.E PLUVAI-.lNA AN 7" UNITIES IN ALBE- Questi.on: But Iookjiere, I've been so the State wouldn't. have to come IMissionary Society. J SERVING THE PEOPLE OF~:EUCKINGHAM COUNTIES .Sur'veys are now being made for planning to build a store rb-ht along and move me out, Wonder l I Mr. and M:'s, J, L, Proffitt and Edit0r . TC?WN OF SCOTTSVILLE Route 15 through Fluvanna. This close to the present edge of Route why my Dad didn't find out ahout \ June were visitors in Richmond ___. .. J Be d M D 'highway is to have a r-ight of way ]5, my land runs right up to the this to sta t wien -r But I guess in this weetc. Mana,'~iJlg.J Editor '__,_.___ ---------------------, mar,'E c earmon of 110 feet. This right of way will' present edge of Route 15 - you those days they didn't ~ave a Zon- 'I Miss M-ary 'Walton attended the Charl()~~~sville Manage;-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~--·---------·-------·_ ltz.abeth Wimer be taken \by the- state as part of I mean to tell' me that a bunch of ing Ordinance td warn a fella I State W.M$. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

What's the Use of Wondering If He's Good Or Bad?: Carousel and The

What’s the Use of Wondering if He’s Good or Bad?: Carousel and the Presentation of Domestic Violence in Musicals. Patricia ÁLVAREZ CALDAS Universidad de Santiago de Compostela [email protected] Recibido: 15.09.2012 Aceptado: 30.09.2012 ABSTRACT The analysis of the 1956 film Carousel (Dir. Henry King), which was based on the 1945 play by Rodgers and Hammerstein, provides a suitable example of a musical with explicit allusions to male physical aggression over two women: the wife and the daughter. The issue of domestic violence appears, thus, in a film genre in which serious topics such as these are rarely present. The film provide an opportunity to study how the expectations and the conventions brought up by this genre are capable of shaping and transforming the presentation of Domestic Violence. Because the audience had to sympathise with the protagonists, the plot was arranged to fulfil the conventional pattern of a romantic story inducing audiences forget about the dark themes that are being portrayed on screen. Key words: Domestic violence, film, musical, cultural studies. ¿De qué sirve preocuparse por si es bueno o malo?: Carrusel y la presentación de la violencia doméstica en los musicales. RESUMEN La película Carrusel (dirigida por Henry King en 1956 y basada en la obra de Rodgers y Hammerstein de 1945), nos ofrece un gran ejemplo de un musical que realiza alusiones explícitas a las agresiones que ejerce el protagonista masculino sobre su esposa y su hija. El tema de la violencia doméstica aparece así en un género fílmico en el que este tipo de tratamientos rara vez están presentes. -

THE BALLET Corps De Ballet of Metropolitan, Chicago and San Francisco Draw up Schedules of Minimum Pay and Conditions of Employment

A~MA Official Organ of the AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS, INC. 576 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. Telephone: LOngacre 3-6223 Branch of the ASSOCIATED ACTORS AND ARTISTES OF AMERICA FEBRUARY~APRIL, 1939 VOLUME IV, Nos. 2, 3, 4 Representatives HolJywood Office: San Francisco: Chicago; ERNEST CHARLBS, Asst. Exec. Seq. VIC CONNORS-THBODOlUl HALE LEO CURLEY 6331 HollyWood Boulevard 220 Bush Street 162 East Ohio Street Officers: Board of Governors: ',LAWltBNCl!• TIBBETT • • ZLATKO BALOKOVIC ERNST LERT ': President WALTER DAMlt9sCH RUTH BRETON LAURITZ MELCHIOR RUDOLPH .GANZ JASCHA HEI~~ FlIANK CHAPMAN JAMES MELTON '1st Vice.PresMent RICHARD CROOKS EzlO PINZA HOWARD HANSON RICHARD BO'Nl'lLU MISCHA ELMAN ERNEST HUTCHESON 2nd Vi&e.~Jitlenl EVA GAUTHIER SERGE KOUSSllVIT?..KY' MARG CHARLES HACKETT Jrd esitli:nJ LEHMANN EDWARD HARRIs FlIAN" .SHERIDAN, ELISABtrR H()llPF'm ;;JOHN MCCORMACK 4th' Tliie"President JULIUS 'HUEHN DANIBL HARRIS EDWIN HUGHES Jth Vice·President JOS!; ITUIlDI Q MARro Fl!.EDERICK JAGBL MAlUIK WINDHBD( r ding Secretary EFlUIM ZrMBALIST PlIAnt( LA FoRGE TrealNl'er • LEO PtsCHBR Edited by L. T. CARR ExecNtitle Secretary Editorial Advisory Committee: .Hll'NlI!t JAl'l'E EDWARD HAl!.l!.IS, Chairman ~, CfIfI1Htil RICHARD BONELLI LEO PlSCHlIR GUILD • • • N THIS issue is reported the signing of agreements be I tween AGMA and NBC Artists Service and Columbia authority of an Artists' union in regula Concerts Corporation, the two largest managers of musical and the policies pursued in the concert a~ts in this country. The contracts are the full and final has implications of the grave~t importance, 'not ft)1~fthe symbol of the new order which began in American musical artists directly m~naged by the .~;chains, but £ot~al1milsicaf Hfe with the formation of AGMA and the beginning of its artists.