Fulltext/ED536776.Pdf Bray, M., Adamson, B., & Mason, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEAM ISRAEL Dan Leibovich, Kibutz Manara, Israel a New Star Was Born

TEAM ISRAEL Dan Leibovich, Kibutz Manara, Israel A new star was born… After hearing from Adi Yeger (Vice President of Special Olympics Israel) all about the impressive basketball game of the Special Olympics Israel team versus the Special Olympics Italy team and all about the almost impossible win, we could not help ourselves and just had to interview Dan Leibovich, a player and assistant to the coach of the Special Olympics Israel team. Dan has undoubtedly brought the big win to the team! As with most of the basketball players, our Dan is tall — rising up to the sky, and with his smooth tongue he managed to tell us all about his excitement for the Special Olympics World Games and the game versus Special Olympics Italy in particular. “At halftime of the game our team was 20 points behind, and then what seemed to be the impossible became reality!” Dan proved his ability, scoring 25 points and making three blocks in spite of the massive guarding of the Special Olympics Italy team and brought, along with his team mates, the victory to his team. How did you get to the Special Olympic World Games? “Two years ago I moved to Shafririm School in Givat Haim, and the gym teachers told me they wanted me for Special Olympics. Before moving to Shafririm, I played football on the Hapoel Upper Galilee team. When I got involved with Special Olympics I was very happy and my family supported me.” How does it feel to be in Ireland? “I’m very glad to be here. -

Image Copyright Hans Erni / WWSF the WWSF Foundation Logo Was Kindly Donated by WWSF Message from the President & CEO Hans Erni, Switzerland’S Most Famous Artist

(c) Image copyright Hans Erni / WWSF The WWSF Foundation logo was kindly donated by WWSF Message from the President & CEO Hans Erni, Switzerland’s most famous artist. right to development, equality and peace, and lobby their government for robust implemen- 2018 Achievements tation of the unfinished business of gender and 2019 Outlook equality and women’s rights. The world has today a powerful roadmap pro- Dear Partners and vided by the Sustainable Development Agen- Friends, da 2030, and there can be no more excuse not to deliver lasting results. WWSF Global Newsletter Empowering Women and Children In closing a good year Femmes et Enfants-Maitriser sa vie with many activities and Regarding the WWSF Children-Youth section, Mujeres y Niños – Dirijan sus vidas events, we wish to say we are happy to share that some very impres- Edition No. 25 – 2018 «Thank You» to all our sive activities were organized by coalition partners, friends and member organizations in several countries, Published by sponsors who accom- briefly described in this report. In addition, WWSF Women’s World Summit Foundation panied us through our WWSF published online a more detailed “Glob- Case postale 5490, CH-2011 Genève 11 al Impact Report 2018. Tel +41 (0 ) 22 738 66 19 annual program of work. Fax + 41 (0) 22 738 82 48 Indeed, partnerships [email protected] - www.woman.ch with generous relation- In 2018, WWSF included in its 19 Days cam- www.ruban-blanc.ch ships and networks are paign Kit a new dimension to remind coalition WWSF, a Swiss Foundation and an the new leadership for members “that it will take compassion to help International empowerment network for women, children and youth, empowering the Social Good and drive the de- end violence against children and youth”, serves with its annual initiatives, velopment agenda for solving local problems. -

Maya Angelou.Pdf

"I am reading her books and learning from her wisdom all the time. Thank you!" - A.m. Reimer "Translation of " Rafteed walay na az dil_e_ma "( a Persian line ) You are gone Maya ><><><>< but not from our hearts !!" - Abbas R "So much love and light! A true warrior of light!" - Abigail C-P "I remember reading her tales at hat parties;). I owned her words as if they were my own. She embodied grace and confidence, and she inspired me to be as phenomenal as she was. #soiconic" - Abigail A "AMEN AMEN She was ANNOINTED,CHOOSEN...SERVANT OF ELOHIM A-M-E-N HALLELUJAH AMEN" - Abraham B "Maya Angelou, you made me a phenomenal woman and no longer living like an orphan. Thanks be to God that you were there throughout the pages of your books, I saw a light everytime life puts me in a corner. It was God and you. I am forever grateful" - Achan A "Maya Angelou your soul will always be alive, and YOU will always be inspiring people, like me. What a WOMAN!" - Adama G "A remarkable woman of substance, a truly once in a lifetime phenomenon. I missed her so much." - Adebisi A "Remarkable woman. Read her Book at age 16." - Adriana P "I was blessed to get the chance to see her at Flint Center , Cupertino Ca. After that nite I changed my life! Meaning I was a yes person! I learned to say im sorry at this time I cant help you! I didnt know how! Thank You for My Strength on saying that word! NO!" - Agnes H "Lady extraordiniere, loved that woman" - Aida G "My true icon, inspiration, role model, my iron lady. -

ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT We Are ISAAA

in 2019 ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT We are ISAAA 1998 1995 ISAAA Centers established 2000 1996 New institutional 1992 structure, with focus on ISAAA was The first AmeriCenter, global review Africa & SEAsia programs founded External review SEAsiaCenter was EuroCenter, & AsiaCenter of transgenic (AmeriCenter for admin showed ISAAA established exceeded its plants was functions) goals released Global Knowledge 1991 1994 Center on Crop AfriCenter Biotechnology was established Inception Years of ISAAA With the advent of agri-biotechnology decades ago, Through the years, ISAAA shares the benefits of crop there has been an unprecedented opportunity to biotechnology to various stakeholders, particularly alleviate poverty and hunger. Majority of the global resource-poor farmers in developing countries. population was poor, and most of the underprivileged We target to achieve this through best practices in depend on agriculture for their survival. Many of them knowledge sharing for a global audience and holistic are subsistence farmers without access to agricultural support to technology development. innovations. If there was no action done to include them in the agri-biotech revolution, we would have ISAAA’s global knowledge-sharing network and missed the opportunity to dramatically improve their strong linkages with the research and development lives. ISAAA was created to ensure that agri-biotech continuum lay out a robust pathway towards delivers its promise to these small resource-poor facilitating informed decision making on biotech crop farmers. acceptance and adoption. Bundled with an array of support services such as capacity building, regulatory Dr. Clive James, who was the Deputy Director General oversight, and impact assessment, ISAAA’s approach at CIMMYT, was commissioned by the World Bank leads the way towards the timely delivery of biotech together with Gabrielle Persley (of International applications, especially in the developing countries Service for National Agricultural Research) to where such technologies are needed the most. -

2018 Global Impact Report

WWSF Annual Campaign: 19 Days of Activism for the prevention of violence against children and youth 1-19 November 2018 2018 Global Impact Report Selected examples of activities and events organized by coalition member organizations during the 19 Days campaign The report is published online www.woman.ch Photo: Stellah Reever Nsereko, Miss Uganda (c) Amani Initiative Against Teenage Pregnancy & Early Marriage https://www.facebook.com/www.amaniinitiative.org/ Recipient of the 2018 WWSF Prize for Innovative Prevention Activities, P. 14-15 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from WWSF Executive Director p.4 Global Campaign Poster 2018 p.5 List of 2018 Active Coalition Member Organizations p.6 - 7 Recipient Organization: Prize for Innovative Prevention Activities 2018 p.8 Campaign Activities by Region: p.14 Africa p.15 - 18 Asia p.19 - 21 Europe p.22 - 43 Poster 19 November - World Day for prevention of violence against children & Youth, in synergy with 20 November - International Children’s Day p.44 - 45 Women’s World Summit Foundation (WWSF) Children - Youth Section Global Campaign: Prevention of Violence against Children & Youth POB 5490 - 1211 Geneva 11 - Switzerland - Tel: +41 (0) 22 738 66 19 email: [email protected] - http://www.woman.ch IBAN: CH1900 7880 0005070 1412 - SWIFT: BCGECHGGXXX Clearing/CB: 788 The 19 Days Campaign is an active Member of the Global partnership to end violence against children. Supporting the UN SDG Agenda 2030 Advocating for the realization of the UN Sustainable Development Goals - Agenda 2030 # Target 16.2: “End abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against and torture of children”. -

The African Species of Landolphia P. Beauv. Series of Revisions Of

WAGENINGEN AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY PAPERS 92-2(1992 ) TheAfrica n specieso f Landolphia P. Beauv. Series ofrevision s of Apocynaceae XXXIV by J.G.M.Persoon , F.J.H.va nDilst ,R.P . Kuijpers, A.J.M. Leeuwenberg and G.J.A.Von k Departmentof Plant Taxonomy Wageningen,Agricultural University, TheNetherlands Dateo fpublicatio n 24-9-1992 Wageningen By Agricultural University Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Generalpar t 2 Geographicaldistributio n 2 Habit and growth 3 Relationship toothe rgener a ; 4 Keyt oth egener ao fLandolphiina e 5 Taxonomicpar t 6 Thegenu sLandolphi a 6 Sectionalarrangemen t 7 Discussion onth erelationshi p ofth esection san d their delimitation 10 Keyt oth especie s 11 TheAfrica n species 16 Hybrid 205 Nominanuda 206 Excluded species 206 Acknowledgement 209 Indexo fexsiccata e 209 Index ofscientifi c names 228 Abstract LandolphiaP .Beauv. ,a n apocynaceous genusdistinc t bycoroll a tubeusuall y thickened above the anthers, glabrous fruits and mostly dense inflorescences, hasbee n revised for mainland Africa. Thegenu s nowcount s 50specie s on that continent.I ti sconfine d towe tan dseasonall ydr yAfric a andMadagascar ,wher e 10-13endemi c species are found. Five new names and four new combinations were necessary: for three new species and the two other new names and the four newcombination sfo r speciesformerl y housedi nAnthoclitandra an dApha- nostylis,gener a reduced to synonyms of Landolphia here. The latter two new names are for species of which the epithets were otherwise occupied. Relation ships to the nearest genera are discussed. Keys are given to identify specimens to the genera in Landolphiinae, now counting 9 genera, and to the species in Landolphia. -

Africa Cic Launch

EYE HEALTH AFRICA CIC LAUNCH Saturday 2020th NOVEMBER 28 Your Eye Health Matters to Us OVERVIEW 01 Background 02 Who We Are 03 What We Do 05 Our Team 06 Founder and CEO 07 Profiles 20 Launch Program 22 Speakers 24 Guest of Honour Sponsors THE LAUNCH Background Eye Health Africa, was founded by Miss Primrose Magala, a British Senior Ophthalmic Nurse at Lon- donsʼ famous Moorfields Eye Hospital. She is also the author of ‘The Eye Opener ‘. Eye Health Africa CIC is powered by health profes- sionals passionate about delivering high quality ophthalmologic care across the continent of Africa. The ultimate goal of Eye Health Africa is to create long term and sustainable ophthalmic institutions in Africa, to allow each country to deliver world class eye care for themselves. They do this by advocating for aid and partnership with local and international organisations. The organisation aims to share and exchange knowledge, and transfer practical skills to support the urgent need to build capacity for eye care services in Africa. “Share your knowledge. Itʼs a way to achieve immortality”. – Dalai Lama SERVICES Eye Health Africa CIC provides a wide range of services. We provide training for health We host eye health camps. professionals. Our team is composed of world We donate state of the art class ophthalmologists and equipment to help health specialist nurses. professionals screen their population. We aim to train professionals that express their interest in screening and those that are keen to enhance their knowledge on the subject area. 1 WHO WE ARE Eye Health Africa CIC was founded by Miss Primrose Magala, a British Senior Ophthalmic Nurse at Lon- donsʼ famous Moorfields Eye Hospital. -

May 2017 Edition

Volume XXXV No. 5 May 2017 Montreal, QC www.filipinostar.org Chief Justice Sereno speaks up on martial law declaration lead to abuses "depends" on whether ABS-CBN News government branches would ensure Posted at May 26 2017 04:03 fidelity to the Constitution and on public vigilance. 'If properly implemented, martial law declaration won't be a burden' "If President Duterte and the MANILA- While strict compliance with aforementioned government authorities the Constitution would spare the avoid the gross historical sins of Mister nation from abuses under martial law, Marcos and his agents, then our country Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno might reap the benefits of the legitimate use on Friday called on graduates of the of the provisions on Martial Law in the 1987 Ateneo de Manila University to "make Constitution," said Sereno. a stand" against the rising "culture of impunity" and "blatant threats" facing She said the 1987 Constitution in "clear and fundamental rights and freedoms. unmistakable language rejects and absolutely prohibits the particular kind of martial law that began in our country in The Chief Justice speaks to the September of 1972," in reference to the Ateneo de Manila University Class of wrongdoings under Marcos' rule. 2017, "The Atenean Facing Martial Law". Still, she urged graduates to take action against a pervading "culture, a pattern" of Speaking in graduation rites of her "apathy, rage, and despair." alma mater, Sereno for the first time publicly addressed President Rodrigo "As we face the days following President Duterte's declaration of martial law in Duterte’s declaration of martial law in Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno delivers her commencement Mindanao, it behooves us to ask what we Mindanao, citing constitutional speech at the Ateneo de Manila University. -

Justice in Conflict: the ICC in Libya and Northern Uganda

The London School of Economics and Political Science Justice in Conflict: The ICC in Libya and Northern Uganda Mark Kersten A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London. 8 September 2014. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,693 words. 2 Abstract The thesis examines the effects of interventions by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on peace, justice and conflict processes in northern Uganda and Libya. The 'peace versus justice' debate, wherein it is argued that the ICC has either positive or negative effects on 'peace’, has spawned in response to the Court's interventions into active and ongoing conflicts. The thesis is a response to and engagement with this debate. Despite often seeming persuasive, claims within the 'peace versus justice' debate have failed to set out a coherent research agenda on how to study the effects of the ICC's interventions on 'peace'. -

Can She Bring the Crown Home?

38THE BEAT, Friday, December 7, 2018 BEAUTY Can she bring the crown home? FACTFILE Continued from page 37 30 slot, highlighted the plight of Born: February 11, 1996 teenage pregnancies in Uganda, Parents: Alice Kyamulesire and were careful in selecting the girls to asking MWO to join hands with SO THEN... Charles Sembera participate.” her to fight the challenge. During Education: Wobulenzi Parents’ Namutebi continues: “Abenakyo the session, she said: “My Beauty School (2004-2008), St. Joseph’s can bring the crown because she is With A Purpose project is fighting LESSONS FROM MISS Girl S S Nsambya (2009-2013) doing well online and has the other teenage pregnancies as one out of Merryland High School (2013-2015) WORLD WINNERS attributes, such as height, speaks four girls aged between 13 and 17 is Makerere University Business School well, she can stand her ground and either pregnant or a mother. This is Last year, India’s Manushi (2015-2018) has the brain. If she does not win the disheartening. Chillar’s win as the Miss Employment: Former usher with crown, I am certain she will finish in She cited a story of a one 12-year- Annellah Ushering Company World tied her country top seven and maybe be Miss World old Daisy, in eastern Uganda, who with Venezuela as the Africa. She has the beauty queen was molested by her father and nation with the most Miss look.” grandfather, resulting in pregnancy, World wins, at six. The Santa Anzo, the chief executive and, after, asked the judges: “Imagine two countries are trailed officer of Arapapa fashion house, giving birth to your grandfather’s E\WKH8. -

Nears Miss World Crown

FRIDAYS IN THE THE FRIDAYS JUSTBEAT GOT A WHOLE LOT BETTER 07.12.18 ABENAKYO NEARS MISS WORLD CROWN HAVING SCOOPED A SLOT AMONG THE TOP 30 IN THE GLOBAL BEAUTY PAGEANT, THE NEED TO VOTE FOR QUIIN ABENAKYO HAS DRIVEN UGANDANS TO THE INTERNET. BUT DOES SHE HAVE WHAT IT TAKES TO BRING THE CROWN HOME? The call to vote for Miss Uganda Authority executive director’s the 118 contestants from all over the quality of girls in the competition. Miss Uganda Quiin Quiin Abenakyo in the Miss tweet read: “This is good news the world. This came after she beat Former Miss Uganda Leah Kagasa, Abenakyo excited the World beauty pageant has been for Uganda. Congratulations @ Argentina’s Victoria Sotto in the in 2017 cited racism in the global immense. Links have been shared AbenakyoQuiin! Let’s all vote and Head to Head Challenge, a category competition in an interview with New country last weekend on WhatsApp groups, Facebook and support our very own Quiin to bring that pits 20 contestants in pairs, to Vision, the reason she gave for her Twitter. From politicians, corporate the #MissWorld2018 crown home! present to a panel of judges in 90 failure to snag the tiara. when she made it to the companies, celebrities to the media, VOTE.” seconds, the work they are doing She said: “There is a lot of racism in top 30 in the Miss World many have joined the campaign to Speaker of Parliament Rebecca in their home countries to support the competition. I think it is not good vote for their girl, ahead of the Miss Kadaga posted: “This is good news! Beauty with a Purpose. -

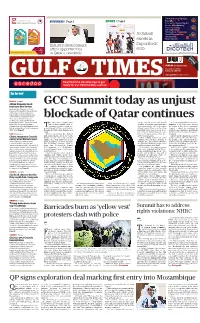

GCC Summit Today As Unjust Blockade of Qatar Continues

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Al-Sulaiti excels in Industry development Superstock off ers ‘opportunities 600 to Qataris, residents’ published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11027 December 9, 2018 Rabia II 2, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals In brief REGION | Confl ict 20mn Yemenis food GCC Summit today as unjust insecure due to war Around 20mn Yemenis are food insecure, UN agencies said yesterday, adding the conflict ravaging the impoverished country was the key driver behind rising hunger levels. “As many as 20mn Yemenis are blockade of Qatar continues food insecure in the world’s worst humanitarian crisis,” a joint statement he 39th GCC Summit takes sation, Riyadh politicised Umrah “It is very regrettable that the con- by the UN’s Food and Agriculture place today in Riyadh amid an and Haj, depriving Qatari nationals tinuation of the Gulf crisis exposed Organisation (FAO), the children’s fund Tongoing blockade on Qatar im- from performing one of the main the failure of the Gulf Co-operation Unicef and the World Food Programme posed in June 2017 by Saudi Arabia, obligations of Islam. On the other Council ... which has weakened its (WFP) said. Page 15 Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates and hand Haj visas were used as a po- ability to face challenges and threats Egypt. litical tool to intimidate poor coun- and marginalised its role in the region,” ASIA | Diplomacy Without even giving the slightest tries in Africa to declare their loy- he added. hint, Saudi Arabia closed the Salwa alty to Saudi Arabia.