Uncertainty, Intelligence, and National Security Decision Making David R. Mandela* and Daniel Irwinb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Correlative-Based Fallacies

Fallacies In Argument 本文内容均摘自 Wikipedia,由 ode@bdwm 编辑整理,请不要用于商业用途。 为方便阅读,删去了原文的 references,见谅 I Correlative-based fallacies False dilemma The informal fallacy of false dilemma (also called false dichotomy, the either-or fallacy, or bifurcation) involves a situation in which only two alternatives are considered, when in fact there are other options. Closely related are failing to consider a range of options and the tendency to think in extremes, called black-and-white thinking. Strictly speaking, the prefix "di" in "dilemma" means "two". When a list of more than two choices is offered, but there are other choices not mentioned, then the fallacy is called the fallacy of false choice. When a person really does have only two choices, as in the classic short story The Lady or the Tiger, then they are often said to be "on the horns of a dilemma". False dilemma can arise intentionally, when fallacy is used in an attempt to force a choice ("If you are not with us, you are against us.") But the fallacy can arise simply by accidental omission—possibly through a form of wishful thinking or ignorance—rather than by deliberate deception. When two alternatives are presented, they are often, though not always, two extreme points on some spectrum of possibilities. This can lend credence to the larger argument by giving the impression that the options are mutually exclusive, even though they need not be. Furthermore, the options are typically presented as being collectively exhaustive, in which case the fallacy can be overcome, or at least weakened, by considering other possibilities, or perhaps by considering a whole spectrum of possibilities, as in fuzzy logic. -

A Statistical Guide for the Ethically Perplexed Preamble Introduction

A Statistical Guide for the Ethically Perplexed Lawrence Hubert and Howard Wainer Preamble The meaning of \ethical" adopted here is one of being in accordance with the accepted rules or standards for right conduct that govern the practice of some profession. The profes- sions we have in mind are statistics and the behavioral sciences, and the standards for ethical practice are what we try to instill in our students through the methodology courses we offer, with particular emphasis on the graduate statistics sequence generally required for all the behavioral sciences. Our hope is that the principal general education payoff for competent statistics instruction is an increase in people's ability to be critical and ethical consumers and producers of the statistical reasoning and analyses faced in various applied contexts over the course of their careers. Introduction Generations of graduate students in the behavioral and social sciences have completed mandatory year-long course sequences in statistics, sometimes with difficulty and possibly with less than positive regard for the content and how it was taught. Prior to the 1960's, such a sequence usually emphasized a cookbook approach where formulas were applied un- thinkingly using mechanically operated calculators. The instructional method could be best characterized as \plug and chug," where there was no need to worry about the meaning of what one was doing, only that the numbers could be put in and an answer generated. This process would hopefully lead to numbers that could then be looked up in tables; in turn, p-values were sought that were less than the magical .05, giving some hope of getting an attendant paper published. -

The Emperor's Tattered Suit: the Human Role in Risk Assessment

The Emperor’s Tattered Suit: The Human Role in Risk Assessment and Control Graham Creedy, P.Eng, FCIC, FEIC Process Safety and Loss Management Symposium CSChE 2007 Conference Edmonton, AB October 29, 2007 1 The Human Role in Risk Assessment and Control • Limitations of risk assessment (acute risk assessment for major accident control in the process industries) • Insights from other fields • The human role in risk assessment – As part of the system under study – In conducting the study • Defences 2 Rationale • Many of the incidents used to sensitize site operators about process safety “would not count” in a classical risk assessment, e.g. for land use planning • It used to be that only fatalities counted, though irreversible harm is now also being considered • Even so, the fatalities and/or harm may still not count, depending on the scenario • The likelihood of serious events may be understated 3 Some limitations in conventional risk assessment: consequences • “Unexpected” reaction and environmental effects, e.g. Seveso, Avonmouth • Building explosion on site, e.g. Kinston, Danvers • Building explosion offsite, e.g. Texarkana • Sewer explosion, e.g. Guadalajara • “Unexpected” vapour cloud explosion, e.g. Buncefield • “Unexpected” effects of substances involved, e.g. Tigbao • Projectiles, e.g. Tyendinaga, Kaltech • Concentration of blast, toxics due to surface features • “Unexpected” level of protection or behaviour of those in the affected zone, e.g. Spanish campsite, Piedras Negras • Psychological harm (and related physical harm), e.g. 2EH example 4 Some limitations in conventional risk assessment: frequency • Variability in failure rate due to: – Latent errors in design: • Equipment (Buncefield) • Systems (Tornado) • Procedures (Herald of Free Enterprise) – Execution errors due to normalization of deviance Indicators such as: • Safety culture (Challenger, BP, EPA) • Debt (Kleindorfer) • MBAs among the company’s top managers? (Pfeffer) • How realistic are generic failure rate data? (e.g. -

Data Science As Political Action: Grounding Data Science in a Politics of Justice

Data Science as Political Action: Grounding Data Science in a Politics of Justice Ben Green [email protected] Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Abstract In response to increasing public scrutiny and awareness of the social harms associated with data-driven algorithms, the field of data science has rushed to adopt ethics training and principles. Such efforts, however, are ill-equipped to address broad matters of social Justice. Instead of a narrow vision of ethics grounded in vague principles and professional codes of conduct, I argue, the field must embrace politics (by which I mean not simply debates about specific political parties and candidates but more broadly the collective social processes that influence rights, status, and resources across society). Data scientists must recognize themselves as political actors engaged in normative constructions of society and, as befits political practice, evaluate their work according to its downstream impacts on people’s lives. I Justify this notion in two parts: first, by articulating why data scientists must recognize themselves as political actors, and second, by describing how the field can evolve toward a deliberative and rigorous grounding in a politics of social Justice. Part 1 responds to three arguments that are commonly invoked by data scientists when they are challenged to take political positions regarding their work: “I’m Just an engineer,” “Our Job isn’t to take political stances,” and “We should not let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” In confronting these arguments, I articulate how attempting to remain apolitical is itself a political stance—a fundamentally conservative one (in the sense of maintaining the status quo rather than in relation to any specific political party or movement)—and why the field’s current attempts to promote “social good” dangerously rely on vague and unarticulated political assumptions. -

Examples of Mental Mistakes Made by Systems Engineers While Creating Tradeoff Studies

Studies in Engineering and Technology Vol. 1, No. 1; February 2014 ISSN 2330-2038 E-ISSN 2330-2046 Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://set.redfame.com Examples of Mental Mistakes Made by Systems Engineers While Creating Tradeoff Studies James Bohlman1 & A. Terry Bahill1 1Systems and Industrial Engineering, University of Arizona, USA Correspondence: Terry Bahill, Systems and Industrial Engineering, University of Arizona, 1622 W. Montenegro, Tucson AZ 85704-1822, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 21, 2013 Accepted: November 4, 2013 Available online: November 21, 2013 doi:10.11114/set.v1i1.239 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/set.v1i1.239 Abstract Problem statement: Humans often make poor decisions. To help them make better decisions, engineers are taught to create tradeoff studies. However, these engineers are usually unaware of mental mistakes that they make while creating their tradeoff studies. We need to increase awareness of a dozen specific mental mistakes that engineers commonly make while creating tradeoff studies. Aims of the research: To prove that engineers actually do make mental mistakes while creating tradeoff studies. To identify which mental mistakes can be detected in tradeoff study documentation. Methodology: Over the past two decades, teams of students and practicing engineers in Bahill’s Systems Engineering courses wrote the system design documents for an assigned system. On average, each of these document sets took 100 man-hours to create and comprised 75 pages. We used 110 of these projects, two dozen government contractor tradeoff studies and three publicly accessible tradeoff studies. We scoured these document sets looking for examples of 28 specific mental mistakes that might affect a tradeoff study. -

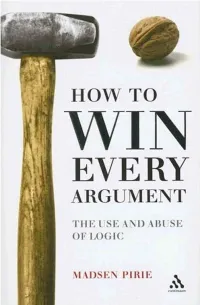

How to Win Every Argument: the Use and Abuse of Logic (2006)

How to Win Every Argument The Use and Abuse of Logic Also available from Continuum What Philosophers Think - Julian Baggini and Jeremy Stangroom What Philosophy Is - David Carel and David Gamez Great Thinkers A-Z - Julian Baggini and Jeremy Stangroom How to Win Every Argument The Use and Abuse of Logic Madsen Pirie •\ continuum • ••LONDON • NEW YORK To Thomas, Samuel and Rosalind Continuum International Publishing Group The Tower Building 15 East 26th Street 11 York Road New York, NY 10010 London SE1 7NX © Madsen Pirie 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Madsen Pirie has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 0826490069 (hardback) Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Typeset by YHT Ltd, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Acknowledgments viii Introduction ix Abusive analogy 1 Accent 3 Accident 5 Affirming the consequent 7 Amphiboly 9 Analogical fallcy 11 Antiquitam, argumentum ad 14 Apriorism 15 Baculum, argumentum ad 17 Bifurcation 19 Blinding with science 22 The -

The Declining Utility of Analyzing Burdens of Persuasion

ALLEN (DO NOT DELETE) 8/8/2018 12:23 PM The Declining Utility of Analyzing Burdens of Persuasion Ronald J. Allen* FESTSCHRIFT FOR MICHAEL RISINGER The title of this panel is “The Weight of Burdens: Decision Thresholds and how to get ordinary people to operationalize them the way we want them to.” I am a somewhat odd choice to be answering that question, since, apart from a few aberrational efforts during my misbegotten youth1 when I was not thinking clearly about the distinction between normative and positive work, my research program is as positive as I can make it. The closest to this title that an aspect of my research program attempts to shed light on is the question of the nature of juridical proof rather than what it should be or how do we get jurors to act in one way or another. To be sure, once one has a confident grasp of the answer to that question, normative proselytizing can begin, by those who wish to do it, either to enhance or modify the structure in place—but that is not a serious motivation of my work. I cheerily assume that, generally speaking (a point soon to be developed further), fact finders (judges are no different from jurors) do exactly what we ask them to do, which is to determine to their best ability what actually happened concerning a litigated event, and apply the law as they understand it to the facts that are found.2 For me, one of the interesting questions is the extent to which the * John Henry Wigmore Professor of Law, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law; President, International Association of Evidence and Forensic Science; Fellow, The Forensic Science Institute, China University of Political Science and Law. -

MIRANDA's PRACTICAL EFFECT: SUBSTANTIAL BENEFITS and VANISHINGLY SMALL SOCIAL COSTS Stephen J

90 NWULR 500 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 1 90 Nw. U. L. Rev. 500 (Cite as: 90 Nw. U. L. Rev. 500) Northwestern University Law Review Winter, 1996 *500 MIRANDA'S PRACTICAL EFFECT: SUBSTANTIAL BENEFITS AND VANISHINGLY SMALL SOCIAL COSTS Stephen J. Schulhofer [FNa] Copyright © 1996 Northwestern University School of Law, Northwestern University Law Review; Stephen J. Schulhofer; I. Empirical Estimates of Miranda 's Impact ...................... 503 A. Are the Immediate Post- Miranda Studies Relevant Today? ... 506 1. Common Methodological Flaws .............................. 506 2. Adaptation to Miranda .................................... 507 B. Drawing Inferences from Before-After Comparisons .......... 510 1. Long-term Trends ......................................... 511 2. Competing Causal Events .................................. 512 3. Instability .............................................. 513 4. Baselines ................................................ 514 C. Before-After Changes at Specific Sites .................... 516 1. Pittsburgh ............................................... 516 2. New York County .......................................... 517 3. Philadelphia ............................................. 524 4. 'Seaside City' ........................................... 528 5. New Haven ................................................ 530 6. Washington, D.C........................................... 530 7. New Orleans .............................................. 531 8. Kansas City ............................................. -

Arxiv:1704.00450V1 [Math.HO] 3 Apr 2017 Epeadtesto Epeta R O Al Hs Eslc Sharp Lack Sets These Tall

OLD AND NEW APPROACHES TO THE SORITES PARADOX BRUNO DINIS Abstract. The Sorites paradox is the name of a class of paradoxes that arise when vague predicates are considered. Vague predicates lack sharp boundaries in extension and is therefore not clear exactly when such predicates apply. Several approaches to this class of paradoxes have been made since its first formulation by Eubulides of Miletus in the IV century BCE. In this paper I survey some of these approaches and point out some of the criticism that these approaches have received. A new approach that uses tools from nonstandard analysis to model the paradox is proposed. The knowledge came upon me, not quickly, but little by little and grain by grain. (Charles Dickens in David Copperfield) 1. To be or not to be a heap This paper concerns the paradoxes which arise when several orders of mag- nitude are considered. These paradoxes are part of the larger phenomenon known as vagueness. Indeed, [...] vagueness can be seen to be a feature of syntactic categories other than predicates. Names, adjectives, adverbs and so on are all susceptible to paradoxical sorites reasoning in a derivative sense. [20] Vague predicates share at least the following features: (1) Admit borderline cases (2) Lack sharp boundaries (3) Are susceptible to sorites paradoxes Borderline cases are the ones where it is not clear whether or not the predicate arXiv:1704.00450v1 [math.HO] 3 Apr 2017 applies, independently of how much one knows about it. For instance, most basket- ball players are clearly tall and most jockeys are clearly not tall. -

Comparing Homeland Security Risks Using a Deliberative Risk Ranking Methodology

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Browse Reports & Bookstore TERRORISM AND Make a charitable contribution HOMELAND SECURITY For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the Pardee RAND Graduate School View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the Pardee RAND Graduate School (PRGS) dissertation series. PRGS dissertations are produced by graduate fellows of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, the world’s leading producer of Ph.D.’s in policy analysis. The dissertation has been supervised, reviewed, and approved by the graduate fellow’s faculty committee. Comparing Homeland Security Risks Using a Deliberative Risk Ranking Methodology Russell Lundberg PARDEE RAND GRADUATE SCHOOL Comparing Homeland Security Risks Using a Deliberative Risk Ranking Methodology Russell Lundberg This document was submitted as a dissertation in September 2013 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the doctoral degree in public policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. -

Planning Theory & Practice Living with Flood Risk/The More We Know, The

This article was downloaded by: [University of Waikato] On: 12 January 2014, At: 14:22 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Planning Theory & Practice Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rptp20 Living with flood risk/The more we know, the more we know we don't know: Reflections on a decade of planning, flood risk management and false precision/Searching for resilience or building social capacities for flood risks?/ Participatory floodplain management: Lessons from Bangladesh/Planning and retrofitting for floods: Insights from Australia/ Neighbourhood design considerations in flood risk management/Flood risk management – Challenges to the effective implementation of a paradigm shift Mark Scott a , Iain White b , Christian Kuhlicke c , Annett Steinführer d , Parvin Sultana e , Paul Thompson e , John Minnery f , Eoin O'Neill g , Jonathan Cooper h , Mark Adamson i & Elizabeth Russell h a School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Policy, University College Dublin , Ireland b School of Environment and Development, University of Manchester , Manchester , UK c Department Urban and Environmental Sociology , Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ , Leipzig , Germany d Institute for Rural Studies, Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institute – vTI , Braunschweig , Germany e Flood Hazard Research Centre, Middlesex University , London , UK f School of Geography Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland , Brisbane , Australia g School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Policy, University College Dublin , Ireland h JBA Consulting , Limerick , Ireland i Office of Public Works , Dublin , Ireland Published online: 19 Mar 2013. -

Designing for User-Facing Uncertainty in Everyday Sensing and Prediction

Designing for User-facing Uncertainty in Everyday Sensing and Prediction Matthew Jeremy Shaver Kay A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Julie A. Kientz, Chair Shwetak N. Patel, Chair James Fogarty Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Computer Science & Engineering © Copyright 2016 Matthew Jeremy Shaver Kay University of Washington Abstract Designing for User-facing Uncertainty in Everyday Sensing and Prediction Matthew Jeremy Shaver Kay Chairs of Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Julie A. Kientz Human Centered Design & Engineering WRF Entrepreneurship Endowed Professor Shwetak N. Patel Computer Science & Engineering As we reach the boundaries of sensing systems, we are increasingly building and deploying ubiquitous computing solutions that rely heavily on inference. This is a natural trend given that sensors have physical limitations in what they can actually sense. Often, there is also a strong desire for simple sensors to reduce cost and deployment burden. Examples include using low-cost accelerometers to track step count or sleep quality (Fitbit), using microphones for cough tracking [57] or fall detection [72], and using electrical noise and water pressure monitoring to track appliances’ water and electricity use [34]. A common thread runs across these systems: they rely on inference, hence their output has uncertainty—it has an associated error that researchers attempt to minimize—and this uncertainty is user-facing—it directly affects the quality of the user experience. As we push more of these sorts of sensing and prediction systems into our everyday day lives, we should ask: does the uncertainty in their output affect how people use and trust these systems? If so, how can we design them to be better? While existing literature suggests communicating uncertainty may affect trust, little evidence of this effect in real, deployed systems has been available.