The Declining Utility of Analyzing Burdens of Persuasion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Review, Vol. X

29 Neutrosophic Vague Set Theory Shawkat Alkhazaleh1 1 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science and Art Shaqra University, Saudi Arabia [email protected] Abstract In 1993, Gau and Buehrer proposed the theory of vague sets as an extension of fuzzy set theory. Vague sets are regarded as a special case of context-dependent fuzzy sets. In 1995, Smarandache talked for the first time about neutrosophy, and he defined the neutrosophic set theory as a new mathematical tool for handling problems involving imprecise, indeterminacy, and inconsistent data. In this paper, we define the concept of a neutrosophic vague set as a combination of neutrosophic set and vague set. We also define and study the operations and properties of neutrosophic vague set and give some examples. Keywords Vague set, Neutrosophy, Neutrosophic set, Neutrosophic vague set. Acknowledgement We would like to acknowledge the financial support received from Shaqra University. With our sincere thanks and appreciation to Professor Smarandache for his support and his comments. 1 Introduction Many scientists wish to find appropriate solutions to some mathematical problems that cannot be solved by traditional methods. These problems lie in the fact that traditional methods cannot solve the problems of uncertainty in economy, engineering, medicine, problems of decision-making, and others. There have been a great amount of research and applications in the literature concerning some special tools like probability theory, fuzzy set theory [13], rough set theory [19], vague set theory [18], intuitionistic fuzzy set theory [10, 12] and interval mathematics [11, 14]. Critical Review. Volume X, 2015 30 Shawkat Alkhazaleh Neutrosophic Vague Set Theory Since Zadeh published his classical paper almost fifty years ago, fuzzy set theory has received more and more attention from researchers in a wide range of scientific areas, especially in the past few years. -

Cotangent Similarity Measures of Vague Multi Sets

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 120 No. 7 2018, 155-163 ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.acadpubl.eu/hub/ Special Issue http://www.acadpubl.eu/hub/ Cotangent Similarity Measures of Vague Multi Sets S. Cicily Flora1 and I. Arockiarani2 1,2Department of Mathematics Nirmala College for Women, Coimbatore-18 Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper throws light on a simplified technique to solve the selection procedure of candidates using vague multi set. The new approach is the enhanced form of cotangent sim- ilarity measures on vague multi sets which is a model of multi criteria group decision making. AMS Subject Classification: 3B52, 90B50, 94D05. Key Words and Phrases: Vague Multi sets, Cotan- gent similarity measures, Decision making. 1 Introduction The theory of sets, one of the most powerful tools in modern mathe- matics is usually considered to have begun with Georg Cantor[1845- 1918]. Considering the uncertainity factor, Zadeh [7] introduced Fuzzy sets in 1965. If repeated occurrences of any object are al- lowed in a set, then the mathematical structure is called multi sets [1]. As a generalizations of multi set,Yager [6] introduced fuzzy multi set. An element of a fuzzy multi set can occur more than once with possibly the same or different membership values. The concept of Intuitionistic fuzzy multi set was introduced by [3]. Sim- ilarity measure is a very important tool to determine the degree of similarity between two objects. Using the Cotangent function, a new similarity measure was proposed by wang et al [5]. -

Research Article Vague Filters of Residuated Lattices

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Discrete Mathematics Volume 2014, Article ID 120342, 9 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/120342 Research Article Vague Filters of Residuated Lattices Shokoofeh Ghorbani Department of Mathematics, 22 Bahman Boulevard, Kerman 76169-133, Iran Correspondence should be addressed to Shokoofeh Ghorbani; [email protected] Received 2 May 2014; Revised 7 August 2014; Accepted 13 August 2014; Published 10 September 2014 AcademicEditor:HongJ.Lai Copyright © 2014 Shokoofeh Ghorbani. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Notions of vague filters, subpositive implicative vague filters, and Boolean vague filters of a residuated lattice are introduced and some related properties are investigated. The characterizations of (subpositive implicative, Boolean) vague filters is obtained. We prove that the set of all vague filters of a residuated lattice forms a complete lattice and we find its distributive sublattices. The relation among subpositive implicative vague filters and Boolean vague filters are obtained and it is proved that subpositive implicative vague filters are equivalent to Boolean vague filters. 1. Introduction of vague ideal in pseudo MV-algebras and Broumand Saeid [4] introduced the notion of vague BCK/BCI-algebras. In the classical set, there are only two possibilities for any The concept of residuated lattices was introduced by Ward elements: in or not in the set. Hence the values of elements and Dilworth [5] as a generalization of the structure of the in a set are only one of 0 and 1. -

A Vague Relational Model and Algebra 1

http://www.paper.edu.cn A Vague Relational Model and Algebra 1 Faxin Zhao, Z.M. Ma*, and Li Yan School of Information Science and Engineering, Northeastern University Shenyang, P.R. China 110004 [email protected] Abstract Imprecision and uncertainty in data values are pervasive in real-world environments and have received much attention in the literature. Several methods have been proposed for incorporating uncertain data into relational databases. However, the current approaches have many shortcomings and have not established an acceptable extension of the relational model. In this paper, we propose a consistent extension of the relational model to represent and deal with fuzzy information by means of vague sets. We present a revised relational structure and extend the relational algebra. The extended algebra is shown to be closed and reducible to the fuzzy relational algebra and further to the conventional relational algebra. Keywords: Vague set, Fuzzy set, Relational data model, Algebra 1 Introduction Over the last 30 years, relational databases have gained widespread popularity and acceptance in information systems. Unfortunately, the relational model does not have a comprehensive way to handle imprecise and uncertain data. Such data, however, exist everywhere in the real world. Consequently, the relational model cannot represent the inherently imprecise and uncertain nature of the data. The need for an extension of the relational model so that imprecise and uncertain data can be supported has been identified in the literature. Fuzzy set theory has been introduced by Zadeh [1] to handle vaguely specified data values by generalizing the notion of membership in a set. And fuzzy information has been extensively investigated in the context of the relational model. -

I Correlative-Based Fallacies

Fallacies In Argument 本文内容均摘自 Wikipedia,由 ode@bdwm 编辑整理,请不要用于商业用途。 为方便阅读,删去了原文的 references,见谅 I Correlative-based fallacies False dilemma The informal fallacy of false dilemma (also called false dichotomy, the either-or fallacy, or bifurcation) involves a situation in which only two alternatives are considered, when in fact there are other options. Closely related are failing to consider a range of options and the tendency to think in extremes, called black-and-white thinking. Strictly speaking, the prefix "di" in "dilemma" means "two". When a list of more than two choices is offered, but there are other choices not mentioned, then the fallacy is called the fallacy of false choice. When a person really does have only two choices, as in the classic short story The Lady or the Tiger, then they are often said to be "on the horns of a dilemma". False dilemma can arise intentionally, when fallacy is used in an attempt to force a choice ("If you are not with us, you are against us.") But the fallacy can arise simply by accidental omission—possibly through a form of wishful thinking or ignorance—rather than by deliberate deception. When two alternatives are presented, they are often, though not always, two extreme points on some spectrum of possibilities. This can lend credence to the larger argument by giving the impression that the options are mutually exclusive, even though they need not be. Furthermore, the options are typically presented as being collectively exhaustive, in which case the fallacy can be overcome, or at least weakened, by considering other possibilities, or perhaps by considering a whole spectrum of possibilities, as in fuzzy logic. -

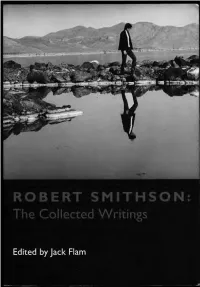

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

A Statistical Guide for the Ethically Perplexed Preamble Introduction

A Statistical Guide for the Ethically Perplexed Lawrence Hubert and Howard Wainer Preamble The meaning of \ethical" adopted here is one of being in accordance with the accepted rules or standards for right conduct that govern the practice of some profession. The profes- sions we have in mind are statistics and the behavioral sciences, and the standards for ethical practice are what we try to instill in our students through the methodology courses we offer, with particular emphasis on the graduate statistics sequence generally required for all the behavioral sciences. Our hope is that the principal general education payoff for competent statistics instruction is an increase in people's ability to be critical and ethical consumers and producers of the statistical reasoning and analyses faced in various applied contexts over the course of their careers. Introduction Generations of graduate students in the behavioral and social sciences have completed mandatory year-long course sequences in statistics, sometimes with difficulty and possibly with less than positive regard for the content and how it was taught. Prior to the 1960's, such a sequence usually emphasized a cookbook approach where formulas were applied un- thinkingly using mechanically operated calculators. The instructional method could be best characterized as \plug and chug," where there was no need to worry about the meaning of what one was doing, only that the numbers could be put in and an answer generated. This process would hopefully lead to numbers that could then be looked up in tables; in turn, p-values were sought that were less than the magical .05, giving some hope of getting an attendant paper published. -

A New Approach of Interval Valued Vague Set in Plants L

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 120 No. 7 2018, 325-333 ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.acadpubl.eu/hub/ Special Issue http://www.acadpubl.eu/hub/ A NEW APPROACH OF INTERVAL VALUED VAGUE SET IN PLANTS L. Mariapresenti*, I. Arockiarani** *[email protected] Department of mathematics, Nirmala college for women, Coimbatore Abstract: This paper proposes a new mathematical model which anchors on interval valued vague set theory. An interval valued interview chat with interval valued vague degree is framed. Then in- terval valued vague weighted arithmetic average operators (IVWAA) are defined to aggregate the vague information from the symptomes. Also a new distance measure is formulated for our diagnosis Keywords: Interview chart, aggregate operator, interval valued vague weighted arithmetic average, distance measure. 1. Introduction The fuzzy set theory has been utilized in many approaches to model the diagnostic process.[1, 2, 4, 8, 11, 12, 14]. Sanchez [9] invented a full developed relationships modeling theory of symptoms and diseases using fuzzy set. Atanassov[3] in 1986 defined the notion of intuitionistic fuzzy sets, which is the generalization of notion of Zadeh’s[13] fuzzy set. In 1993 Gau and Buehrer [6] initated the concept of vague set theory which was the generalization of fuzzy set with membership and non membership function. The vague set theory has been explored by many authors and has been applied in different disciplines. The task of a agricultural consultant is to diagnose the disease of the plant. In agriculture diagnosis can be regarded as a label given by the agricultural consultant to describe and synthesize the status of the diseased plant. -

Feature Article: a New Similarity Measure for Vague Sets 15

14 Feature Article: Jingli Lu, Xiaowei Yan, Dingrong Yuan and Zhangyan Xu A New Similarity Measure for Vague Sets Jingli Lu, Xiaowei Yan, Dingrong Yuan, Zhangyan Xu Abstract--Similarity measure is one of important, effective and their similarity should not be 1. In reference [5] Dug Hun Hong widely-used methods in data processing and analysis. As vague set put forward another similarity measure MH, according to the theory has become a promising representation of fuzzy concepts, in formulae of MH, we can obtain the similarity of vague values [0.3, this paper we present a similarity measure approach for better 0.7] and [0.4, 0.6] is M ([0.3,0.7],[0.4,0.6]) = 0.9 , in the same understanding the relationship between two vague sets in applica- H tions. Compared to existing similarity measures, our approach is far model, we can get M H ([0.3,0.6],[0.4,0.7]) = 0.9 . In a voting more reasonable, practical yet useful in measuring the similarity model, the vague value [0.3, 0.7] can be interpreted as: “the vote between vague sets. for a resolution is 3 in favor, 3 against and 4 abstentions”; [0.4, Index Terms-- Fuzzy sets, Vague sets, Similarity measure 0.6] can be interpreted as: “the vote for a resolution is 4 in favor, 4 against and 2 abstention”. [0.3, 0.6] and [0.4, 0.7] can have I. INTRODUCTION similar interpretation. Intuitively, [0.3, 0.7] and [0.4, 0.6] may be more similar than [0.3, 0.6] and [0.4, 0.7]. -

The Emperor's Tattered Suit: the Human Role in Risk Assessment

The Emperor’s Tattered Suit: The Human Role in Risk Assessment and Control Graham Creedy, P.Eng, FCIC, FEIC Process Safety and Loss Management Symposium CSChE 2007 Conference Edmonton, AB October 29, 2007 1 The Human Role in Risk Assessment and Control • Limitations of risk assessment (acute risk assessment for major accident control in the process industries) • Insights from other fields • The human role in risk assessment – As part of the system under study – In conducting the study • Defences 2 Rationale • Many of the incidents used to sensitize site operators about process safety “would not count” in a classical risk assessment, e.g. for land use planning • It used to be that only fatalities counted, though irreversible harm is now also being considered • Even so, the fatalities and/or harm may still not count, depending on the scenario • The likelihood of serious events may be understated 3 Some limitations in conventional risk assessment: consequences • “Unexpected” reaction and environmental effects, e.g. Seveso, Avonmouth • Building explosion on site, e.g. Kinston, Danvers • Building explosion offsite, e.g. Texarkana • Sewer explosion, e.g. Guadalajara • “Unexpected” vapour cloud explosion, e.g. Buncefield • “Unexpected” effects of substances involved, e.g. Tigbao • Projectiles, e.g. Tyendinaga, Kaltech • Concentration of blast, toxics due to surface features • “Unexpected” level of protection or behaviour of those in the affected zone, e.g. Spanish campsite, Piedras Negras • Psychological harm (and related physical harm), e.g. 2EH example 4 Some limitations in conventional risk assessment: frequency • Variability in failure rate due to: – Latent errors in design: • Equipment (Buncefield) • Systems (Tornado) • Procedures (Herald of Free Enterprise) – Execution errors due to normalization of deviance Indicators such as: • Safety culture (Challenger, BP, EPA) • Debt (Kleindorfer) • MBAs among the company’s top managers? (Pfeffer) • How realistic are generic failure rate data? (e.g. -

Vague Filter and Fantastic Filter of Bl-Algebras

Advances in Mathematics: Scientific Journal 9 (2020), no.8, 5561–5571 ADV MATH SCI JOURNAL ISSN: 1857-8365 (printed); 1857-8438 (electronic) https://doi.org/10.37418/amsj.9.8.25 VAGUE FILTER AND FANTASTIC FILTER OF BL-ALGEBRAS S. YAHYA MOHAMED AND P. UMAMAHESWARI1 ABSTRACT. In this paper, we investigate some properties of vague filter of a BL- algebra. Also, introduce the notion of a vague fantastic filter with illustration. Further, we discuss some of related properties. Finally, we obtain equivalent condition and extension property of a vague fantastic filter. 1. INTRODUCTION Zadeh, [11] introduced the concept of fuzzy set theory in 1965. The notion of intuitionistic fuzzy sets was introduced by Atanassov, [1, 2] in 1986 as an extension of fuzzy set. Gau and Buehrer [3] proposed the concept of vague set in 1993, by replacing the value of an element in a set with a subinterval of [0; 1]: Namely, there are two membership functions: a truth membership function tS and a false membership function fS, where tS(x) is a lower bound of the grade of membership of x derived from the ”evidence of x” and fS(x) is a lower bound on the negation of x derived from the ”evidence against x” and tS(x)+fS(x) ≤ 1: Thus, the grade of membership in vague set S is subinterval [tS(x); 1 − fS(x)] of [0, 1]. Hajek, [4] introduced the notion of BL-algebras as the structures for Basic Logic. Recently, the authors [7–10] introduce the definitions of vague filter, vague prime, Boolean filters, and vague implicative and vague positive 1corresponding author 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. -

A Survey on Domination in Vague Graphs with Application in Transferring Cancer Patients Between Countries

mathematics Article A Survey on Domination in Vague Graphs with Application in Transferring Cancer Patients between Countries Yongsheng Rao 1 , Ruxian Chen 2, Pu Wu 1, Huiqin Jiang 1 and Saeed Kosari 1,* 1 Institute of Computing Science and Technology, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou 510006, China; [email protected] (Y.R.); [email protected] (P.W.); [email protected] (H.J.) 2 School of Mathematics and Information Science, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou 510006, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-156-2229-6383 Abstract: Many problems of practical interest can be modeled and solved by using fuzzy graph (FG) algorithms. In general, fuzzy graph theory has a wide range of application in various fields. Since indeterminate information is an essential real-life problem and is often uncertain, modeling these problems based on FG is highly demanding for an expert. A vague graph (VG) can manage the uncertainty relevant to the inconsistent and indeterminate information of all real-world problems in which fuzzy graphs may not succeed in bringing about satisfactory results. Domination in FGs theory is one of the most widely used concepts in various sciences, including psychology, computer sciences, nervous systems, artificial intelligence, decision-making theory, etc. Many research studies today are trying to find other applications for domination in their field of interest. Hence, in this paper, we introduce different kinds of domination sets, such as the edge dominating set (EDS), the total edge dominating set (TEDS), the global dominating set (GDS), and the restrained dominating set (RDS), in product vague graphs (PVGs) and try to represent the properties of each by giving Citation: Rao, Y.; Chen, R.; Wu, P.; some examples.