Belief: a Critical Analysis of the Matrix Trilogy Shannan Lojeski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Believing in Fiction I

Believing in Fiction i The Rise of Hyper-Real Religion “What is real? How do you define real?” – Morpheus, in The Matrix “Television is reality, and reality is less than television.” - Dr. Brian O’Blivion, in Videodrome by Ian ‘Cat’ Vincent ver since the advent of modern mass communication and the resulting wide dissemination of popular culture, the nature and practice of religious belief has undergone a Econsiderable shift. Especially over the last fifty years, there has been an increasing tendency for pop culture to directly figure into the manifestation of belief: the older religious faiths have either had to partly embrace, or strenuously oppose, the deepening influence of books, comics, cinema, television and pop music. And, beyond this, new religious beliefs have arisen that happily partake of these media 94 DARKLORE Vol. 8 Believing in Fiction 95 – even to the point of entire belief systems arising that make no claim emphasises this particularly in his essay Simulacra and Simulation.6 to any historical origin. Here, he draws a distinction between Simulation – copies of an There are new gods in the world – and and they are being born imitation or symbol of something which actually exists – and from pure fiction. Simulacra – copies of something that either no longer has a physical- This is something that – as a lifelong fanboy of the science fiction, world equivalent, or never existed in the first place. His view was fantasy and horror genres and an exponent of a often pop-culture- that modern society is increasingly emphasising, or even completely derived occultism for nearly as long – is no shock to me. -

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception. Modern Day science and technology has been crucial in the development of the modern film industry. In the past, directors have been confined by unwieldy, primitive cameras and the most basic of special effects. The contemporary possibilities now available has enabled modern film to become more dynamic and versatile, whilst also being able to better capture the performance of actors, and better display scenes and settings using special effects. As the prevalence of technology in society increases, film makers have used their medium to express thematic, moral and ethical concerns of technology in human life. The films I will be looking at: The Matrix, directed by the Wachowskis, and Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, both explore strong themes of technology. The theme of technology is expanded upon as the directors of both films explore the use of augmented reality and its effects on the human condition. Through the use of camera angles, costuming and lighting, the Witkowski brothers represent the idea that technology is dangerous. During the sequence where neo is unplugged from the Matrix, the directors have cleverly combines lighting, visual and special effects to craft an ominous and unpleasant setting in which the technology is present. Upon Neo’s confrontation with the spider drone, the use of camera angles to establishes the dominance of technology. The low-angle shot of the drone places the viewer in a subordinate position, making the drone appear powerful. The dingy lighting and poor mis-en-scene in the set further reinforces the idea that technology is dangerous. -

What's in a Name? the Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 9-2008 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2008). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Math Horizons 16.1, 18-21. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/12 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In lieu of an abstract, here is the article's first paragraph: In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix to illustrate the nature of evidence and how it shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician, I usually field questions elatedr to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Disciplines Mathematics Comments Article copyright 2008 by Math Horizons. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in the Matrix Films and Popular Culture

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2010 The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation James F. McGrath. "The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture" Visions of the Human in Science Fiction and Cyberpunk. Ed. Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch. Oxford, UK: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2010. 161-172. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/ facsch_papers/556/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edited by Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Abstract The movie The Matrix and its sequels draw explicitly on imagery from a number of sources, including in particular Buddhism, Christianity, and the writings of Jean Baudrillard. A perspective is offered on the perennial philosophical question ‘What is real?’, using language and symbols drawn from three seemingly incompatible world views. In doing so, these movies provide us with an insight into the way popular culture makes eclectic use of various streams of thought to fashion a new reality that is not unrelated to, and yet is nonetheless distinct from, its religious and philosophical undercurrents and underpinnings. -

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. How, then, can we describe the affective and temporal experience of digital media, whose algorithmic processes elude conscious thought and yet form the (im)material conditions of much of our life today? In order to address this question, this chapter examines several examples of digital media works (films, games) that can serve as central mediators of the shift to a properly post-cinematic regime, focusing particularly on the aesthetic dimensions of the popular and transmedial “bullet time” effect. Looking primarily at the first Matrix film | 1 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality (1999), as well as digital games like the Max Payne series (2001; 2003; 2012), I seek to explore how the use of bullet time serves to highlight the medial transformation of temporality and affect that takes place with the advent of the digital—how it establishes an alternative configuration of perception and agency, perhaps unprecedented in the cinematic age that was dominated by what Deleuze has called the “movement-image.”[1] 1. -

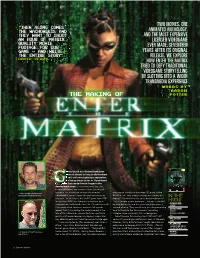

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Download Films / Movies Card Game (PDF)

Back to the Future Blade Runner ET 1985 / sci-fi 1982 / sci-fi 1982 / sci-fi Robert Zemeckis (director) Ridley Scott (director) Steven Spielberg (director) Michael J Fox Harrison Ford Dee Wallace Christopher Lloyd The Godfather Harry Potter and the The Exorcist 1972 / crime thriller Philosopher's Stone 1973 / horror Francis Ford Coppola (director) 2001 / fantasy William Friedkin (director) Maron Brando Chris Columbus (director) Ellen Burstyn Al Pacino Daniel Radcliffe Jaws Raiders of the Lost Ark Goldfinger 1975 / thriller 1981 / action / adventure 1964 / spy thriller Steven Spielberg (director) Steven Spielberg (director) Guy Hamilton (director) Roy Scheider Harrison Ford Sean Connery Robert Shaw Jurassic Park Mad Max The Lion King 1993 / sci-fi 1979 / action 1994 / cartoon / musical Steven Spielberg (director) George Miller (director) Roger Allers / Rob Minkoff Sam Neill Mel Gibson (directors) Laura Dern Joanne Samuel Mission Impossible Pirates of the Caribbean: 1996 / spy / action Pinocchio Dead Man's Chest Brian De Palma (director) 1940 2006 / fantasy adventure Tom Cruise cartoon / musical / fantasy Gore Verbinski (director) Paula Wagner Johnny Depp Apocalypse Now Schindler's List The Matrix 1979 / war film 1993 / historical drama 1999 / sci-fi / action Francis Ford Coppola (director) Steven Spielberg (director) The Wachowskis (directors) Marlon Brando Liam Neeson Keanu Reeves Martin Sheen Ralph Fiennes Carrie-Anne Moss Titanic Crazy Rich Asians The Lord of the Rings: The 1997 / disaster / romance 2018 / romantic comedy Fellowship of the Ring James Cameron (director) Jon M. Chu (director) 2001 / fantasy / adventure Leonardo DiCaprio Constance Wu Peter Jackson (director) Kate Winslet Gemma Chan Elijah Wood Ian McKellen Toy Story The Sound of Music The Dark Knight 1995 1965 / musical / drama 2008 / superhero computer-animated comedy Robert Wise (director) Christopher Nolan (director) John Lasseter (director) Julie Andrews Christian Bale Tom Hanks (voice) Christopher Plummer Michael Caine © ELTbase.com 2019. -

Matrix : from Representation to Simulation and Beyond

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 2006 Matrix : from representation to simulation and beyond Bryx, Adam http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/3345 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons The Matrix: From Representation to Simulation and Beyond A thesis submitted to the Department of English Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Adam Bryx May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliothèque et 1 ^1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. -

Bruno Mölder

ISSN 0234-8160 wmm KOIK ON KOKKU ... MATRIX? Bruno Mölder: Kas me oleme ajud purgis? Tanel Tammet: Kas me märkaksime endast targemat arvutitsivilisatsiooni? Jüri Eintalu: Kas filosoofia teab, mis homne toob? Slavoj Zižek: Meie tegelik passiivsus versus virtuaalne kõikvõimsus. Unenäod ja luupainajad Mehis Heinsaare ja Matt Barkeri novellides. Arvustuse all on Andres Herkeli, Aare Pilve ja Kadri Tüüri mõttemasinad. Katrin Kivimaa: maalikunstnik Alice Kask. Piret Bristoli ja Kirsti Oidekivi luulet. • Eesti Kirjanike Liidu ajakiri. Ilmub alates 1986. a. juulist. 18. aastakäik. September, 2003 Nr. 9. SISUKORD Robert Graves Läbi luupainaja 1 Slavoj Žižek Matrix: perversiooni kaks kulge 66 Mehis Heinsaar Vennad uneluses 2 Jüri Eintalu Matrix: filosoofial juhtmed Matt Barker Malmkurat 16 seinast väljät 87 Piret Bristol Luulet 29 Bruno Mölder Matrix purgis 95 Kirsti Oidekivi Luulet 34 Tansl Tammet Matrix, skynet ja sõda Jaak Rand Harilik pealkiri 39 teispoolsusega 106 Mart Kangur Jaak Rand 47 Eksinud... 49 Lotmanieux 53 Vaatenurk Ulo Mattheuis Mõttemasinaga sakraalajas 111 Katrin Kivimaa Meesaktid lõuendil j& Jaanus Adamson Ideaal ja iha 117 vineeril: Alice Kase viimaste maalide Märt Väljataga Subjektiga vastu tõlgendamise projekt 64 ideoloogiamüüri 125 Kujundus: Jüri Kaarma © "Vikerkaar", Fotod Alice Katse maalidest: Toomas Kohv 2003. Esikaanel: ALICE KASK. Kükitav Tagakaanel: ALICE KASK. Näoga mees. Oli, lõuend. 145x210 cm. 20Q2. mees. Õli, lõuend. 145x210 cm. 2003. ROBERT GRAVES Läbi luupainaja Inglise keelest tõlkinud Märt Väljatagu Ärgu sind kunagi lakaku lummamast Koht, kuhu sa ennast mõnikord unistad, Kaugel kõikidest unenägudest, Ega ka need, keda leiad sealt eest, kuigi harva Võid nende seltsi sa istet võtta - Nood taltsutamatud, elavad, õrnad. Kas pole sa kohanud neid? Keda? Nad aja On mähkinud nagu jõe ümber oma maja, Nii et ajaloo teed mööda sinna ei pääse Neid loendama või nimetama. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds.