Changing Land Use and Development in the Enfield Chase Area 1840-1940 Michael Ann Mullen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enfield Society News, 214, Summer 2019

N-o 214, Summer 2019 London Mayor voices concerns over Enfield’s proposals for the Green Belt in the new Local Plan John West ur lead article in the Spring Newsletter referred retention of the Green Belt is also to assist in urban to the Society’s views on the new Enfield Local regeneration by encouraging the recycling of derelict and Plan. The consultation period for the plan ended other urban land. The Mayor, in his draft new London in February and the Society submitted comments Plan has set out a strategy for London to meet its housing Orelating to the protection of the Green Belt, need within its boundaries without encroaching on the housing projections, the need for master planning large Green Belt”. sites and the need to develop a Pubs Protection Policy. Enfield’s Draft Local Plan suggested that Crews Hill was The Society worked closely with Enfield RoadWatch and a potential site for development. The Mayor’s the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) to observations note that, as well as the issue of the Green produce a document identifying all the potential Belt, limited public transport at Crews Hill with only 2 brownfield sites across the Borough. That document trains per hour and the limited bus service together with formed part of the Society’s submission. the distance from the nearest town centre at Enfield Town The Enfield Local plan has to be compatible with the mean that Crews Hill is not a sustainable location for Mayor’s London Plan. We were pleased to see that growth. -

Situation of Polling Stations for the Election of the London Mayor and Assembly Members in the Enfield and Haringey Constituency on Thursday 5 May 2016

Situation of Polling Stations for the election of the London Mayor and Assembly Members in the Enfield and Haringey Constituency on Thursday 5 May 2016 Notice is hereby given that the situation of polling stations at the above election and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: In the area of the London Borough of Enfield Polling Description of Polling Description of Station Situation of polling station persons entitled Station Situation of polling station persons entitled Number to vote Number to vote XA1S Botany Bay Cricket Club, East Lodge Lane, Enfield XAA-1 to XAA-118 XG30S Ellenborough Table Tennis Club, Craddock Road, Enfield XGC-1 to XGC- 1293 XA2A Brigadier Free Church, 36 Brigadier Hill, Enfield XAB-1 to XAB- XG31S Fellowship Hut (Bush Hill Park Recreation Ground), Cecil Avenue, XGD-1 to XGD- 1405 Bush Hill Park 1627 XA2B Brigadier Free Church, 36 Brigadier Hill, Enfield XAB-1406 to XAB- XG32A John Jackson Library, Agricola Place, Bush Hill Park XGE-1 to XGE- 2789 1353 XA3S St. John`s Church Hall, Strayfield Road, Clay Hill XAC-1 to XAC-568 XG32B John Jackson Library, Agricola Place, Bush Hill Park XGE-1354 to XGE- 2584 XA4A St. Lukes Youth Centre, Morley Hill, Enfield XAD-1 to XAD- XG33S St. Marks Hall, Millais Road, (Junction with Main Avenue) XGF-1 to XGF- 1306 1131 XA4B St. Lukes Youth Centre, Morley Hill, Enfield XAD-1307 to XAD- XH34S St. Helier Hall, 12 Eastfield Road, Enfield XHA-1 to XHA- 2531 1925 XA5S Old Ignatian Hall, The Loyola Ground, 147 Turkey Street XAE-1 to XAE-593 XH35A St. -

Centenary Industrial Estate

Well let industrial warehouse investment opportunity UNITS 4-7 CENTENARY INDUSTRIAL ESTATE Jeffreys Road, Enfield, EN3 7UF > Well configured industrial terrace located within one of Enfield’s most > Current rent passing of £177,752 per annum, reflecting a very low Investment established industrial estates. £8.49 per sq ft (£91.44 per sq m). > Strategically positioned close to Mollison Avenue (A1055), with excellent > Freehold. Summary connections to Central London, the M25 motorway and the wider > We are instructed to seek offers in excess of £3,300,000 (Three Million motorway network. and Three Hundred Thousand Pounds) which reflects a Net Initial > 4 interconnecting industrial warehouse units totalling 20,926 sq ft Yield of 5.06% (allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.48%), an estimated (1,944 sq m) GIA. Reversionary Yield of 6.86% and reflecting a low capital value of £158 per sq ft. > Fully let to Tayco Foods Limited on a 10 year lease from 11th January 2018 with a tenant only break option in year 5, providing 4.75 years term certain. Units 4-7, Centenary Industrial Estate Jeffreys Road, Enfield, EN3 7UF TO THE CITY A406 North Circular A1055 A110 Navigation Park Ponders End ENDP Future Phase Cook’s Delight ENDP Scheme A110 SUBJECT PROPERTY A1055 Segro Park, Enfield Rimex Metals Group Esin Cash & Carry Trafalgar Trading Estate Hy Ram Engineering Riverwalk Business Park Midpoint Scheme Mill River Trading Estate Brimsdown Units 4-7, Centenary Industrial Estate Jeffreys Road, Enfield, EN3 7UF ENFIELD LOCK FORTY HILL Location A10 C E A V A RT ENFIELD WASH N ER O H IS ATC L Enfield is a well-established location for industrial and logistics occupiers H L L 0 O A 1 M N 0 E 1 servicing London and the South East. -

Employment & Regeneration in LB Enfield

Employment & Regeneration in LB Enfield September 2015 DRAFT 1 Introduction • LB Enfield and Enfield Transport Users Group (ETUG) have produced a report suggesting some large scale alterations to the bus network. One of the objectives of the report is to meet the demands of the borough’s housing and regeneration aspirations. • TfL have already completed a study of access to health services owing to a re-configuration of services between Chase Farm, North Middlesex and Barnet General Hospital and shared this with LB Enfield. • TfL and LB Enfield have now agreed to a further study to explore the impact of committed development and new employment on bus services in the borough as a second phase of work. 2 DRAFT Aims This study will aim to: •Asses the impact of new housing, employment and background growth on the current network and travel patterns. •Highlight existing shortfalls of the current network. •Propose ideas for improving the network, including serving new Developments. 3 DRAFT Approach to Study • Where do Enfield residents travel to and from to get to work? • To what extent does the coverage of the bus network match those travel patterns? • How much do people use the bus to access Enfield’s key employment areas and to what extent is the local job market expected to grow? • What are the weaknesses in bus service provision to key employment areas and how might this be improved? • What is the expected growth in demand over the next 10 years and where are the key areas of growth? • What short and long term resourcing and enhancements are required to support and facilitate growth in Enfield? 4 DRAFT Methodology •Plot census, passenger survey and committed development data by electoral ward •Overlay key bus routes •Analyse existing and future capacity requirements •Analyse passenger travel patterns and trip generation from key developments and forecast demand •Identify key issues •Develop service planning ideas 5 DRAFT Population Growth According to Census data LB Enfield experienced a 14.2% increase in population between 2001 and 2011 from 273,600 to 312,500. -

Foodbank in Demand As Pandemic Continues

ENFIELD DISPATCH No. 27 THE BOROUGH’S FREE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER DEC 2020 FEATURES A homelessness charity is seeking both volunteers and donations P . 5 NEWS Two new schools and hundreds of homes get go-ahead for hospital site P . 6 ARTS & CULTURE Enfield secondary school teacher turns filmmaker to highlight knife crime P . 12 SPORT How Enfield Town FC are managing through lockdown P . 15 ENFIELD CHASE Restoration Project was officially launched last month with the first of many volunteering days being held near Botany Bay. The project, a partnership between environmental charity Thames 21 and Enfield Council, aims to plant 100,000 trees on green belt land in the borough over the next two years – the largest single tree-planting project in London. A M E E Become a Mmember of Enfield M Dispatch and get O the paper delivered to B your door each month E Foodbank in demand C – find out more R E on Page 16 as pandemic continues B The Dispatch is free but, as a Enfield North Foodbank prepares for Christmas surge not-for-profit, we need your support to stay that way. To BY JAMES CRACKNELL we have seen people come together tial peak in spring demand was Citizens Advice, a local GP or make a one-off donation to as a community,” said Kerry. “It is three times higher. social worker. Of those people our publisher Social Spider CIC, scan this QR code with your he manager of the bor- wonderful to see people stepping “I think we are likely to see referred to North Enfield Food- PayPal app: ough’s biggest foodbank in to volunteer – we have had hun- another big increase [in demand] bank this year, most have been has thanked residents dreds of people helping us. -

Further Draft Recommendations for New Electoral Arrangements in the West Area of Enfield Council

Further draft recommendations for new electoral arrangements in the west area of Enfield Council Electoral review October 2019 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licencing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2019 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Analysis and further draft recommendations in the west of Enfield 1 North and central Enfield 2 Southgate and Cockfosters 11 Have your say 21 Equalities 25 Appendix A 27 Further draft recommendations for the west area of Enfield. -

Enfield's Local Plan: Detailed Green Belt Boundary Review

Enfield’s Local Plan EVIDENCE BASE Detailed Green Belt Boundary Review March 2013 1 Contents Boundary Review Process 2 Introduction 3 National Green Belt Policy 5 Local Context 6 Scope of Review 7 Methodology for boundary strengthening 7 Stage 1: Initial Findings public consultation (July 2011) 9 Stage 2: Further changes post public consultation (April 2012) 10 Stage 3: Final Proposed Submission Changes 10 Appendix A – Proposes Submission Green Belt Changes (under separate cover) Appendix B – Schedule of Reponses to Consultation ((under separate cover) Enfield’s Detailed Green Belt Boundary Review 2 1.0 Boundary Review Process 1.1 The purpose of this report is to set out the recommended boundary changes to Enfield’s Green Belt. The Council published its initial proposed boundary for public consultation in July 2011. Post consultation, 3 additional amendments were made, which subsequently fed into the Draft Green Belt Review Report 2012 that accompanied the Draft Development Management Documents and Policies Map public consultation (May – August 2012). 1.2 The review has made an assessment as to whether the existing boundaries provide robust and defensible boundaries over the Core Strategy plan period, (next 15 to 20 years). In total, the Council is proposing to take forward 30 site changes and effectively proposes a realignment to the Green Belt boundary that results in 13 gains (additional land added 3.71 hectares (9 acres) into the Green Belt designation) and 19 losses ( loss of some 8.06 hectares (19 acres). The gains and losses amount to 32 as two sites, Site 2.1 Enfield Chase – Slopers Pond Cottage, 1‐3 Waggon Road and Site 10.1 Cedar Road / Lavender Gardens resulted in both gains and losses. -

Report and Accounts Year Ended 31St March 2019

Report and Accounts Year ended 31st March 2019 Preserving the past, investing for the future LLancaster Castle’s John O’Gaunt gate. annual report to 31st March 2019 Annual Report Report and accounts of the Duchy of Lancaster for the year ended 31 March 2019 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall (Accounts) Act 1838. annual report to 31st March 2019 Introduction Introduction History The Duchy of Lancaster is a private In 1265, King Henry III gifted to his estate in England and Wales second son Edmund (younger owned by Her Majesty The Queen brother of the future Edward I) as Duke of Lancaster. It has been the baronial lands of Simon de the personal estate of the reigning Montfort. A year later, he added Monarch since 1399 and is held the estate of Robert Ferrers, Earl separately from all other Crown of Derby and then the ‘honor, possessions. county, town and castle of Lancaster’, giving Edmund the new This ancient inheritance began title of Earl of Lancaster. over 750 years ago. Historically, Her Majesty The Queen, Duke of its growth was achieved via In 1267, Edmund also received Lancaster. legacy, alliance and forfeiture. In from his father the manor of more modern times, growth and Newcastle-under-Lyme in diversification have been delivered Staffordshire, together with lands through active asset management. and estates in both Yorkshire and Lancashire. This substantial Today, the estate covers 18,481 inheritance was further enhanced hectares of rural land divided into by Edmund’s mother, Eleanor of five Surveys: Cheshire, Lancashire, Provence, who bestowed on him Staffordshire, Southern and the manor of the Savoy in 1284. -

Great Northern Route

Wells-next-the-Sea SERVICES AND FACILITIES Burnham Market Hunstanton This is a general guide to the basic daily services. Not all trains stop at Fakenham all stations on each coloured line, so please check the timetable. Dersingham Routes are shown in different colours to help identify the general pattern. Sandringham King’s Lynn Great Northern LIMITED REGULAR ROUTE Watlington SERVICE SERVICE IDENTITY GN1 King’s Lynn and Cambridge Downham Market Wisbech GN2 Cambridge local to Yorkshire, the North East and Scotland Littleport to Norwich GN3 Peterborough and Ipswich GN4 Hertford Ely GN5 Welwyn Waterbeach Other train operators may provide additional services along some of our routes. Peterborough to Newmarket Cambridge North and Ipswich Other train operators’ routes St. Ives Bus links Huntingdon Cambridge Principal stations to Stansted Airport Foxton and London Interchange with London Underground St. Neots Interchange with London Overground Shepreth Interchange with other operators’ train services Sandy Meldreth Biggleswade Royston Ashwell & Morden ACCESSIBILITY Arlesey Baldock Step-Free access between the street and all platforms Letchworth Garden City Hitchin Some step-free access between the street and platforms Step-free access is available in the direction of the arrow Stevenage Watton-at-Stone No step-free access between the street and platforms Knebworth Notes: Hertford North Platform access points may vary and there may not be be step-free access to Welwyn North or between all station areas or facilities. Access routes may be unsuitable for Welwyn Garden City Bayford unassisted wheelchair users owing to the gradient of ramps or other reasons. St. Albans Hatfield Cuffley We want to be able to offer you the best possible assistance, so we ask you to contact us in advance of your journey if possible. -

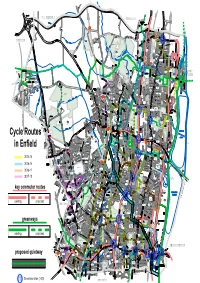

Cycle Routes in Enfield

9'.9;0*#6(+'.& $41:$1740' CREWS HILL Holmesdale Tunnel Open Space Crews Hill Whitewebbs Museum Golf Course of Transport Capel Manor Institute of Lea Valley Lea Valley Horticulture and Field Studies *'465/'4' Sports Centre High School 20 FREEZYWATER Painters Lane Whitewebbs Park Open Space Aylands Capel Manor Primary School Open Space Honilands Primary School Bulls Cross Field Whitewebbs Park Golf Course Keys Meadow School Warwick Fields Open Space Myddelton House and Gardens Elsinge St John's Jubilee C of E Primary School Freezywaters St Georges Park Aylands C of E Primary School TURKEY School ENFIELD STREET LOCK St Ignatius College RC School Forty Hall The Dell Epping Forest 0%4 ENFIELD LOCK Hadley Wood Chesterfield Soham Road Forty Hill Primary School Recreation Ground '22+0) Open Space C of E Primary School 1 Forty Hall Museum (14'56 Prince of Wales Primary School HADLEY Hadley Wood Hilly Fields Gough Park WOOD Primary School Park Hoe Lane Albany Leisure Centre Wocesters Open Space Albany Park Primary School Prince of Oasis Academy North Enfield Hadley Wales Field Recreation Ground Ansells Eastfields Lavender Green Primary School St Michaels Primary School C of E Hadley Wood Primary School Durants Golf Course School Enfield County Lower School Trent Park Country Park GORDON HILL HADLEY WOOD Russet House School St George's Platts Road Field Open Space Chase Community School St Michaels Carterhatch Green Infant and Junior School Trent Park Covert Way Mansion Queen Elizabeth David Lloyd Stadium Centre ENFIELD Field St George's C of E Primary School St James HIGHWAY St Andrew's C of E Primary School L.B. -

Goathland November 2017

Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan Goathland November 2017 2 Contents Summary 3 Introduction 8 Location and context 10 The History of Goathland 12 The ancient street plan, boundaries and open spaces 24 Archaeology 29 Vistas and views 29 The historic buildings of Goathland 33 The little details 44 Character Areas: 47 St. Mary's 47 Infills and Intakes 53 Victorian and Edwardian Village 58 NER Railway and Mill 64 Recommendations for future management 72 Conclusion 82 Bibliography and Acknowledgements 83 Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan for Goathland Conservation Area 2 3 Summary of Significance Goathland is a village of moorland views and grassy open spaces of untamed pasture and boggy verges crossed by ancient stone trods and tracks. These open spaces once separated the dispersed farms that spread between the first village nucleus around the church originally founded in the 12th century, the village pound nearby, and, a grouping of three farms and the mill to the north east, located by the river and known to exist by the early 13th century. This dispersed agricultural settlement pattern started to change in the 1860s as more intakes were filled with villas and bungalows, constructed by the Victorian middle classes arriving by train and keen to visit or stay and admire the moorland views and waterfalls. This created a new village core closer to the station where hotels and shops were developed to serve visitors and residents and this, combined with the later war memorial, has created a village green character and a tighter settlement pattern than seen elsewhere in the village. -

Grouse in the Royal Purple the King of Gamebirds Is Undergoing a Renaissance on Moorland Leased from the Duchy of Lancaster

Grouse in the royal purple The king of gamebirds is undergoing a renaissance on moorland leased from the Duchy of Lancaster. Jonathan Young enjoys the spoils. Photographs by Ann Curtis t would by dismissed by modern art light planes and squadrons of Range Rovers that spaciousness seems almost as impos- critics as Victorian whimsy, but it’s hurtle northwards, ferrying guns from city to sible as boarding the London train with guns, hard to find a sportsman who doesn’t moor, but then the leisured classes truly setters and clad in full tweeds. Yet, for one brief adore George Earl’s Going north, King’s deserved their adjective; and that comfortable moment last season, a century disappeared Cross station, painted in 1893. It depicts position lasted well into the 20th century. Eric into a golden past, thanks to Her Majesty, the Ia sporting party waiting to board the 10 Parker, an Editor of the Field, could still put Duchy of Lancaster and Andrew Pindar. o’clock north, the platform crowded with this poser to readers in 1918; five invitations A party of guns, 12-bores in slips, gundogs gentlemen, ladies and their servants. Minor arrive simultaneously in the post – which in tow, strolled down the high street of mountains of cane rods and gaffs, creels and would they choose: three days’ partridge driv- Pickering, North Yorkshire. Heads were oak-and-leather gun cases are guarded care- ing; a week’s grouse-driving; 10 days on the slightly muzzy after a dinner verging on a fully by the keepers while they control their sea coast of the west of Scotland; a fortnight in banquet at the White Swan Inn.