The Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers: 1921-1938

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

Advertising and the Public Interest. a Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission. INSTITUTION Federal Trade Commission, New York, N.Y

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 074 777 EM 010 980 AUTHCR Howard, John A.; Pulbert, James TITLE Advertising and the Public Interest. A Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission. INSTITUTION Federal Trade Commission, New York, N.Y. Bureau of Consumer Protection. PUB EATE Feb 73 NOTE 575p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$19.74 DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Industry; Commercial Television; Communication (Thought Transfer); Consumer Economics; Consumer Education; Federal Laws; Federal State Relationship; *Government Role; *Investigations; *Marketing; Media Research; Merchandise Information; *Publicize; Public Opinj.on; Public Relations; Radio; Television IDENTIFIERS Federal Communications Commission; *Federal Trade Commission; Food and Drug Administration ABSTRACT The advertising industry in the United States is thoroughly analyzed in this comprehensive, report. The report was prepared mostly from the transcripts of the Federal Trade Commission's (FTC) hearings on Modern Advertising Practices.' The basic structure of the industry as well as its role in marketing strategy is reviewed and*some interesting insights are exposed: The report is primarily concerned with investigating the current state of the art, being prompted mainly by the increased consumes: awareness of the nation and the FTC's own inability to set firm guidelines' for effectively and consistently dealing with the industry. The report points out how advertising does its job, and how it employs sophisticated motivational research and communications methods to reach the wide variety of audiences available. The case of self-regulation is presented with recommendationS that the FTC be particularly harsh in applying evaluation criteria tochildren's advertising. The report was prepared by an outside consulting firm. (MC) ADVERTISING AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST A Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission by John A. -

1930S 1940 1941 1942

CLASS NOTES FOR MORE Incoming Correspondent: Floyd LaBarre Jr. 1930s Army captain, he was a science CLASS NEWS graduate with master’s from The 50 N. Hills Drive Hubert Vance Taylor ’35, Sorbonne in Paris and Kings Rising Sun, MD 21911-1663 For all class formerly of Decatur, Ga., died College London. He pioneered (443) 406-0296 (cell) news, photographs, June 2. He was 99 years old. Just radio and TV advertising, co- (410) 658-5024 (home) baby and wedding six months ago, he baptized two authoring Persuasion in Marketing: announcements, of his great-granddaughers, one The Dynamics of Marketing’s Great reunion planning the daughter of Kurt Rossetti ’90 Untapped Resource. Inducted into 1941 and more, go to and Elizabeth Irvin Rossetti, his the Market Research Hall of Fame community. granddaughter (photo below and in 1992, he was founder and chair Mayo Wills Lanning died lafayette.edu. online, Class of 1990 website). of Schwerin Research Corp. and June 22, a month after celebrating Click on “classes,” On Dec. 30, Taylor baptized also worked for Campbell’s Soup. his 97th birthday. Wife Trudy and then select Margot Jeanne Rossetti, born in Wife Enid survives him. predeceased him. A graduate of your class year. October 2012, daughter of Kurt ’90 Edward C. Helwick Jr. ’38, Washington (N.J.) High School and Elizabeth Irvin Rossetti, 96, Los Angeles, died May 26. A in 1935. A mining engineering Please continue to San Francisco, Calif.; and Caroline government and law graduate, he graduate, he worked for the New send updates to your Vance Pfeffer, born in August edited a humor magazine while Jersey Zinc Co. -

What Are Connecticut College Alumni Doing Five Years After Graduation? a Study of the Class of 2013

What Are Connecticut College Alumni Doing Five Years after Graduation? A Study of the Class of 2013 Wesley M. Morris ’20 and John D. Nugent Office of Institutional Research and Planning July 2018 SUMMARY We found reliable information about the employment and graduate school activities of about 87% of the Class of 2013. Five years after graduating from Connecticut College, about 96% of those for whom we found information were employed, in graduate school, or recent graduates of a degree program. Our students follow a variety of post-undergraduate pathways into jobs, fellowships, internships, degree programs, and non-degree coursework, and nearly half of the Class of 2013 has obtained some form of additional education. OVERVIEW Colleges and universities are now routinely expected to collect and report “outcomes” data on their graduates, primarily on employment, salaries, and graduate and professional school attendance.1 Collecting accurate data on a large portion of a graduated class is tricky, and there is currently no consensus on the best time or method for collecting the data. The National Association of Colleges and Employers has developed a voluntary “first destination” survey that they suggest administering six months following graduation,2 although that timeframe seems primarily aimed at answering the question of how many college graduates quickly secure employment and thus the ability to begin paying off student loans. While important, this is not the only outcome we should be interested in, particularly as an institution offering a liberal arts education, the fruits of which may take years to fully appear. Thus, a longer-term view that looks at graduates’ activities one or more years after graduation has been the approach taken by Connecticut College in our one-year-out and five-year-out studies. -

Online-2020-Stallion-Directory-File.Pdf

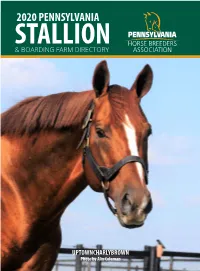

2020 PENNSYLVANIA STALLION & BOARDING FARM DIRECTORY UPTOWNCHARLYBROWN Photo by Alix Coleman 2020 PENNSYLVANIA STALLION & BOARDING FARM DIRECTORY Pennsylvania Horse Contents Breeders Association Pennsylvania, An Elite Breeding Program 4 Breeding Fund FAQ’s 6-7 Officers and Directors PA-Bred Earning Potential 8-9 President: Gregory C. Newell PE Stallion Roster 10-11 Vice President: Robert Graham Stallion Farm Directory 12-13 Secretary: Douglas Black Domicile Farm Directory 14-15 Treasurer: David Charlton Directors: Richard D. Abbott Front Cover Image: Uptowncharlybrown Elizabeth B. Barr Front Cover Photo Credit: Alix Coleman Glenn Brok Peter Giangiulio, Esq. Kate Goldenberg Roger E. Legg, Esq. PHBA Office Staff Deanna Manfredi Elizabeth Merryman Joanne Adams (Bookkeeper) Henry Nothhaft Jennifer Corado (Office Manager) Thomas Reigle Wendi Graham (Racing/Stallion Manager) Dr. Dale Schilling, VMD Jennifer Poorman (Graphic Designer) Charles Zachney Robert Weber (IT Manager) Executive Secretary: Brian N. Sanfratello Assistant Executive Secretary: Vicky Schowe Statistics provided herein are compiled by Pennsylvania Horse Contact Us Breeders Association from data supplied by Stallion and Farm Owners. Data provided or compiled generally is accurate, but 701 East Baltimore Pike, Suite E occasionally errors and omissions occur as a result of incorrect Kennett Square PA 19348 data received from others, mistakes in processing, and other Website: pabred.com causes. Phone: 610.444.1050 The PHBA disclaims responsibility for the consequences, if any, of Email: [email protected] such errors but would appreciate it being called to its attention. This publication will not be sold and can be obtained, at no cost, by visiting our website at www.pabred.com or contacting our office at 610.444.1050. -

I^Igtorical ^Siisociation

American i^igtorical ^siisociation SEVENTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING NEW YORK HEADQUARTERS: HOTEL STATLER DECEMBER 28, 29, 30 Bring this program with you Extra copies 25 cents Please be certain to visit the hook exhibits The Culture of Contemporary Canada Edited by JULIAN PARK, Professor of European History and International Relations at the University of Buffalo THESE 12 objective essays comprise a lively evaluation of the young culture of Canada. Closely and realistically examined are literature, art, music, the press, theater, education, science, philosophy, the social sci ences, literary scholarship, and French-Canadian culture. The authors, specialists in their fields, point out the efforts being made to improve and consolidate Canada's culture. 419 Pages. Illus. $5.75 The American Way By DEXTER PERKINS, John L. Senior Professor in American Civilization, Cornell University PAST and contemporary aspects of American political thinking are illuminated by these informal but informative essays. Professor Perkins examines the nature and contributions of four political groups—con servatives, liberals, radicals, and socialists, pointing out that the continu ance of healthy, active moderation in American politics depends on the presence of their ideas. 148 Pages. $2.75 A Short History of New Yorh State By DAVID M.ELLIS, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, Harry J. Carman HERE in one readable volume is concise but complete coverage of New York's complicated history from 1609 to the present. In tracing the state's transformation from a predominantly agricultural land into a rich industrial empire, four distinguished historians have drawn a full pic ture of political, economic, social, and cultural developments, giving generous attention to the important period after 1865. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

New Paris Telephone

2 www.the-papers.com — the PAPER — Tuesday, May 28, 2019 Rite Choice Foods ™ The right food at the right price KNOW YOUR NEIGHBOR Senior Citizens Discount Every Tuesday Receive 5% Off (Excluding Tobacco & Alcohol) PRICES GOOD MAY 30-JUNE 5, 2019 Executive director has LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1991 BY GARYARY MILLERMILLERL YOU NEVER KNOW THE DISCOUNTS 'LVFRXQW DAVE HAS IN STORE . %(6748$/,7< 'DYH CHECK OUT HIS LIMITED ITEMS ,7(06)25 IN STORE FOR DEEPER %(6735,&(6 DISCOUNTSDIS THAN ADVERTISED heart for at-risk kids PerfectP for Graduation Parties! 6% VANILLA AND CHOCOLATE %\/$85,(/(&+/,71(5 SOFT SERVE ICE CREAM MIX 6WDII:ULWHU 2.5 GALLON BAGS WILL MAKE 4 GALLONS IF YOU NEED 2-3 BAGS, CALL IN 574-773-5462 “I created a mentoring pro- ECKRICH JUMBO, REG., gram in Colorado,” stated Menes- BUN SIZE & CHEESE ¢ sah Nelson, Elkhart. “It was for HOT DOGS 14 OZ.79 youth, ages 12 to 22, involved in AWARD WINNING MEAT DEPARTMENT FOR YOUR GRILLING NEEDS the justice system. I also worked SOME OF THE BEST PRICES ON QUALITY STEAKS IN THE STATE OF INDIANA. LOOK AT OTHER STORES AND LOOK AT OUR PRICES ON for Child Protection Services. HOW MUCH YOU SAVE IN OUR AWARD WINNING MEAT DEPARTMENT I’ve always had a passion for FAMILY PACK $ 49 $ 99 young people who need some NEW YORK STRIP 5 LB. - WHOLE 4 LB. extra guidance. That’s why it’s BONELESS $ 79 been such a good fit for me at Big PORK CHOPS FAMILY PACK 2 LB. Brothers Big Sisters of Elkhart BONELESS $ 19 County. -

Civic Engagement Study

Civic Engagement at Skidmore A Survey of Students, Faculty, and Community Organizations Spring 2005 In the Fall of 2004, sociology professor David Karp and the students1 of Sociology 226 “Social Research Design” conducted a study of civic engagement at Skidmore College. Here we summarize our major findings. Civic Engagement at Skidmore College The president of Skidmore College is a member of Campus Compact, “a national coalition of more than 900 college and university presidents committed to the civic purposes of higher education. To support this civic mission, Campus Compact promotes community service that develops students' citizenship skills and values, encourages partnerships between campuses and communities, and assists faculty who seek to integrate public and community engagement into their teaching and research.” The new strategic plan for Skidmore, entitled “Engaged Liberal Learning: The Plan for Skidmore College: 2005-2015,” gives particular attention to civic engagement: “We will prepare every Skidmore student to make the choices required of an informed, responsible citizen at home and in the world.” Recently, the College received a grant from the Mellon Foundation to develop civic engagement as part of a larger effort to create “a more engaging and guided learning environment.” We define civic engagement as a multidimensional construct that includes the following: Volunteering: Student participation in community service that is not course-related. Service Learning: Experiential learning that links community service and academic coursework. Community Based Research: Research that involves students, faculty and community partners with the goal of solving community problems. SENCER: Science Education for New Civic Engagements and Responsibilities. Interdisciplinary, problem-based courses that apply scientific investigation to contemporary problem solving, i.e., a course of AIDS. -

Louisiana Afl-Cio Union Members' Opinions Regarding Participation, Satisfaction and Leadership

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1978 Louisiana Afl-Cio Union Members' Opinions Regarding Participation, Satisfaction and Leadership. Margaret Mary Stevens Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Stevens, Margaret Mary, "Louisiana Afl-Cio Union Members' Opinions Regarding Participation, Satisfaction and Leadership." (1978). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3217. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3217 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

To the William Howard Taft Papers. Volume 1

THE L I 13 R A R Y 0 F CO 0.: G R 1 ~ ~ ~ • P R I ~ ~ I I) I ~ \J T ~' PAP E R ~ J N 1) E X ~ E R IE S INDEX TO THE William Howard Taft Papers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William Ho-ward Taft Papers VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION AND PRESIDENTIAL PERIOD SUBJECT TITLES MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1972 Library of Congress 'Cataloging in Publication Data United States. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Index to the William Howard Taft papers. (Its Presidents' papers index series) 1. Taft, William Howard, Pres. U.S., 1857-1930. Manuscripts-Indexes. I. Title. II. Series. Z6616.T18U6 016.97391'2'0924 70-608096 ISBN 0-8444-0028-9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $24 per set. Sold in'sets only. Stock Number 3003-0010 Preface THIS INDEX to the William Howard Taft Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 approved August 16, 1957, and amended by Public Laws 87-263 approved September 21, 1961, and 88-299 approved April 27, 1964, to arrange, index, and microfilm the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity," to make the Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. Presidents whose papers are in the Library are: George Washington James K. -

A Century of Struggle

A Century of Struggle To mark the 100th anniversary of the formation of the American Federation of Labor, the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian Institution invited a group of scholars and practitioners "to examine the work, technology, and culture of industrial America . " The conference was produced in cooperation with the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations . The excerpts on the following pages are drawn from papers and comments at that conference, in the Museum's Carmichael Auditorium, November IS and 16, 1986. Mary Kay Rieg, Olivia G. Amiss, and Marsha Domzalski of the Monthly Labor Review provided editorial assistance. Trade unions mirror society in conflict between collectivism and individualism A duality common to many institutions runs through the American labor movement and has marked its shifting fortunes from the post-Civil War period to the present ALICE KESSLER-HARRIS ideology of American trade unions as they developed in Two competing ideas run through the labor movement, as and post-Civil War period. It also tells us something of their they have run through the American past. The first is the the The conglomeration of unions that formed the Na- notion of community-the sense that liberty is nurtured in impact . Union and the 15,000 assemblies of the an informal political environment where the voluntary and tional Labor of Labor responded to the onslaught of industrial- collective enterprise of people with common interests con- Knights the Civil War by searching for ways to reestablish tributes to the solution of problems . Best characterized by ism after of interest that was threatened by a new and the town meeting, collective solutions are echoed in the the community organization of work.