Does Disease Cause Vaccination? Disease Outbreaks and Vaccination Response∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and Child Health Investments in India Emily Oster NBER Working Paper No

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DOES INCREASED ACCESS INCREASE EQUALITY? GENDER AND CHILD HEALTH INVESTMENTS IN INDIA Emily Oster Working Paper 12743 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12743 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2006 Gary Becker, Kerwin Charles, Steve Cicala, Amy Finkelstein, Andrew Francis, Jon Guryan, Matthew Gentzkow, Lawrence Katz, Michael Kremer, Steven Levitt, Kevin Murphy, Jesse Shapiro, Andrei Shleifer, Rebecca Thornton, and participants in seminars at Harvard University, the University of Chicago, and NBER provided helpful comments. I am grateful for funding from the Belfer Center, Kennedy School of Government. Laura Cervantes provided outstanding research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2006 by Emily Oster. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Does Increased Access Increase Equality? Gender and Child Health Investments in India Emily Oster NBER Working Paper No. 12743 December 2006 JEL No. I18,J13,J16,O12 ABSTRACT Policymakers often argue that increasing access to health care is one crucial avenue for decreasing gender inequality in the developing world. Although this is generally true in the cross section, time series evidence does not always point to the same conclusion. This paper analyzes the relationship between access to child health investments and gender inequality in those health investments in India. A simple theory of gender-biased parental investment suggests that gender inequality may actually be non-monotonically related to access to health investments. -

Annual Report 2010

OPR Office of Population Research Princeton University Annual Report 2010 Research Seminars Publications Training Course Offerings Alumni Directory Table of Contents From the Director ……………………………………………….…...…. 3 OPR Staff and Students ……………………………………………….…. 4 Center for Research on Child Wellbeing ………………………………. 10 Center for Health and Wellbeing ………………………………….……. 13 Center for Migration and Development ……………………………….. 15 OPR Financial Support ………………………………………..……..…. 17 OPR Library ………………………………………………..……..…….. 19 OPR Seminars ……………………………………………………..……. 21 OPR Research ………………………………………………….……….. 22 Children Youth and Families………………………….....................….…… 22 Data/Methods ..……….………………………………………..……… 25 Education and Stratification ..………………………………..…………..…. 30 Health and Wellbeing …….…………………………………….......……… 33 Migration and Development …………………….……………..….……….. 42 2010 Publications …………………………………………..……..…….. 45 Working Papers …………………………………....................….……... 45 Publications and Papers ………………………………..…………………… 47 TiiTraining in Demograp hy at PiPrince ton ……..................................…….. 63 Ph.D. Program …………………………………………………….…….... 63 Departmental Degree in Specialization in Population ………………………... 63 Joint-Degree Program ……………………………………………………… 64 Certificate in Demography ……………………………………………….… 64 Training Resources …………………………………………………..…….. 64 Courses …………………………………………………………………… 65 Recent Graduates …………………………………………………..……… 74 Graduate Students …………………………………………………………. 77 Alumni Directory ……………………………………….………………. 83 The OPR Annual report -

Evidence from College Admission Cutoffs in Chile

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES ARE SOME DEGREES WORTH MORE THAN OTHERS? EVIDENCE FROM COLLEGE ADMISSION CUTOFFS IN CHILE Justine S. Hastings Christopher A. Neilson Seth D. Zimmerman Working Paper 19241 http://www.nber.org/papers/w19241 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2013 We thank Noele Aabye, Phillip Ross, Unika Shrestha and Lindsey Wilson for outstanding research assistance. We thank Nadia Vasquez, Pablo Maino, Valeria Maino, and Jatin Patel for assistance with locating, collecting and digitizing data records. J-PAL Latin America and in particular Elizabeth Coble provided excellent field assistance. We thank Ivan Silva of DEMRE for help locating and accessing data records. We thank the excellent leadership and staff at the Chilean Ministry of Education for their invaluable support of these projects including Harald Beyer, Fernando Rojas, Loreto Cox Alcaíno, Andrés Barrios, Fernando Claro, Francisco Lagos, Lorena Silva, Anely Ramirez, and Rodrigo Rolando. We also thank the outstanding leadership and staff at Servicio de Impuestos Internos for their invaluable assistance. We thank Joseph Altonji, Peter Arcidiacono, Ken Chay, Raj Chetty, Matthew Gentzkow, Nathaniel Hilger, Caroline Hoxby, Wojciech Kopczuk, Thomas Lemieux, Costas Meghir, Emily Oster, Jonah Rockoff, Jesse Shapiro, Glen Weyl and participants at University of Chicago, Harvard, Princeton, the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the NBER Public Economics and Education Economics program meetings, and Yale for helpful comments and suggestions. This project was funded by Brown University, the Population Studies and Training Center at Brown, and NIA grant P30AG012810. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

Weighting for External Validity.” Sophie Sun Provided Excellent Research Assistance

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES A SIMPLE APPROXIMATION FOR EVALUATING EXTERNAL VALIDITY BIAS Isaiah Andrews Emily Oster Working Paper 23826 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23826 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2017, Revised January 2021 This paper was previously circulated under the title “Weighting for External Validity.” Sophie Sun provided excellent research assistance. We thank Nick Bloom, Guido Imbens, Matthew Gentzkow, Peter Hull, Larry Katz, Ben Olken, Jesse Shapiro, Andrei Shleifer seminar participants at Brown University, Harvard University and University of Connecticut, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments. Andrews gratefully acknowledges support from the Silverman (1978) Family Career Development chair at MIT, and from the National Science Foundation under grant number 1654234. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Isaiah Andrews and Emily Oster. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. A Simple Approximation for Evaluating External Validity Bias Isaiah Andrews and Emily Oster NBER Working Paper No. 23826 September 2017, Revised January 2021 JEL No. C1,C18,C21 ABSTRACT We develop a simple approximation that relates the total external validity bias in randomized trials to (i) bias from selection on observables and (ii) a measure for the role of treatment effect heterogeneity in driving selection into the experimental sample. -

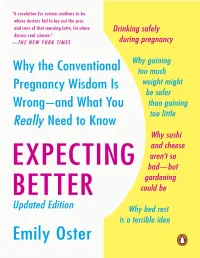

Expecting Better

PENGUIN BOOKS EXPECTING BETTER Emily Oster is a professor of economics at Brown University. She was a speaker at the 2007 TED conference and her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, and Esquire. Oster is married to economist Jesse Shapiro and is also the daughter of two economists. She has two children, Penelope and Finn. Praise for Expecting Better “Expecting Better will be a revelation for curious mothers-to-be whose doctors fail to lay out the pros and cons of that morning latte, let alone discuss real science. And it makes for valuable homework before those harried ob-gyn appointments, even for lucky patients whose doctors are able to talk about the rationale behind their advice.” —The New York Times “Emily Oster combs through hundreds of medical studies to debunk many widely followed dictates: no alcohol, no caffeine, no changing the kitty litter. Her conclusions are startling. Expecting Better walks women through medical literature surrounding every stage of pregnancy, giving them data to make informed decisions about their own pregnancy.” —New York Magazine “It seems that everyone—doctors, yoga teachers, mothers-in-law, and checkout ladies at grocery stores—are members of the pregnancy police. Everyone has an opinion. But not everyone is Emily Oster, a Harvard- trained economics professor at the University of Chicago. To help the many women who reached out to Oster for advice, she compiled her conclusions in her new book, Expecting Better, which she describes as a kind of pregnancy ‘by the numbers.’” —New York Post “[Oster took] a deep dive into research covering everything from wine and weight gain to prenatal testing and epidurals. -

Behavioral Feedback: Do Individual Choices Influence Scientific Results?

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BEHAVIORAL FEEDBACK: DO INDIVIDUAL CHOICES INFLUENCE SCIENTIFIC RESULTS? Emily Oster Working Paper 25225 http://www.nber.org/papers/w25225 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2018 I am grateful for comments to Isaiah Andrews, Amy Finkelstein, Matthew Gentkzow, Ilyana Kuziemko, Matthew Notowidigdo, Jesse Shapiro, Andrei Shleifer, Heidi Williams and participants in a seminar at the US Census. I am grateful to Valeria Zurla, Marco Petterson, Claire Hug, Julian DeGeorgia, Sofia LaPorta, Cathy Yue Bai, James Okun and Geoffrey Kocks for outstanding research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2018 by Emily Oster. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Behavioral Feedback: Do Individual Choices Influence Scientific Results? Emily Oster NBER Working Paper No. 25225 November 2018 JEL No. C18,I12 ABSTRACT In many health domains, we are concerned that observed links - for example, between “healthy” behaviors and good outcomes - are driven by selection into behavior. This paper considers the additional factor that these selection patterns may vary over time. When a particular health behavior becomes more recommended, the take-up of the behavior may be larger among people with other positive health behaviors. -

Diabetes and Diet: Purchasing Behavior Change in Response to Health Information

Diabetes and Diet: Purchasing Behavior Change in Response to Health Information∗ Emily Oster Brown University and NBER November 29, 2017 Abstract Individuals with obesity and related conditions are often reluctant to change their diet. Evaluating the details of this reluctance is hampered by limited data. I use household scanner data to estimate food purchase response to a diagnosis of diabetes. I use a machine learning approach to infer diagnosis from purchases of diabetes-related products. On average, households show significant, but relatively small, calorie reductions. These reductions are concentrated in unhealthy foods, suggesting they reflect real efforts to improve diet. There is some heterogeneity in calorie changes across households, although this heterogeneity is not well predicted by demographics or baseline diet, despite large correlations between these factors and diagnosis. I suggest a theory of behavior change which may explain the limited overall change and the fact that heterogeneity is not predictable. ∗I thank Leemore Dafny, Ben Keys, Jim Salee, Steve Cicala, Aviv Nevo, Matt Notowidigdo, Amy Finkelstein, Andrei Shleifer, Jerome Adda and participants in seminars at Brown University, Columbia University, Harvard University, University of Chicago and Kellogg School of Management for helpful comments. Kejia Ren, Angela Li and David Birke provided excellent research assistance. 1 Introduction In many health contexts, individuals appear resistant to undertaking costly behaviors with health benefits. Examples include resistance to sexual behavior change in the face of HIV (Caldwell et al., 1999; Oster, 2012) and lack of regular cancer screening (DeSantis et al., 2011; Cummings and Cooper, 2011). Among the most common examples of this phenomenon is resistance to dietary improvement among both obese individuals and those with conditions associated with obesity (Ogden et al., 2007). -

Nber Working Paper Series Teaching Practices And

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES TEACHING PRACTICES AND SOCIAL CAPITAL Yann Algan Pierre Cahuc Andrei Shleifer Working Paper 17527 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17527 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2011 We are grateful to Roland Benabou, Antonio Ciccone, Joshua Gottlieb, Lawrence Katz, Jesse Shapiro, Emily Oster, and Fabrizio Zilibotti for helpful comments. We also thank for their comments seminar participants at the University of Chicago, CREI, Harvard, Zurich and to the NBER Cultural Economics workshop. Yann Algan thanks the ERC-Starting Grant for financial support. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2011 by Yann Algan, Pierre Cahuc, and Andrei Shleifer. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Teaching Practices and Social Capital Yann Algan, Pierre Cahuc, and Andrei Shleifer NBER Working Paper No. 17527 October 2011 JEL No. I2,Z1 ABSTRACT We use several data sets to consider the effect of teaching practices on student beliefs, as well as on organization of firms and institutions. In cross-country data, we show that teaching practices (such as copying from the board versus working on projects together) are strongly related to various dimensions of social capital, from beliefs in cooperation to institutional outcomes. -

A Simple Approximation for Evaluating External Validity Bias∗

A Simple Approximation for Evaluating External Validity Bias∗ Isaiah Andrewsy Emily Osterz Harvard and NBER Brown University and NBER March 12, 2019 Abstract We develop a simple approximation that relates the total external validity bias in randomized trials to (i) bias from selection on observables and (ii) a measure for the role of treatment effect heterogeneity in driving selection into the experimental sample. Key Words: External Validity, Randomized Trials JEL Codes: C1 1 Introduction External validity has drawn attention in economics with the growth of randomized trials. Randomized trials provide an unbiased estimate of the average treatment effect in the experimental sample, but this may differ from the average treatment effect in the population of interest. We will refer to such differences as \external validity bias." ∗This paper was previously circulated under the title \Weighting for External Validity." Sophie Sun provided excellent research assistance. We thank Nick Bloom, Guido Imbens, Matthew Gentzkow, Peter Hull, Larry Katz, Ben Olken, Jesse Shapiro, Andrei Shleifer seminar participants at Brown University, Harvard University and University of Connecticut, and an anonymous reviewer for help- ful comments. Andrews gratefully acknowledges support from the Silverman (1978) Family Career Development chair at MIT, and from the National Science Foundation under grant number 1654234. yCorresponding author. Department of Economics, Harvard University, 1805 Cambridge St, Cam- bridge, MA 02138, 617-496-2720, [email protected] zDepartment of Economics, Brown University, 64 Waterman Street, Providence, RI 02912 1 One reason such differences may arise is because individuals (or other treatment units) actively select into the experiment. For example, Bloom, Liang, Roberts and Ying (2015) report results from an evaluation of working from home in a Chinese firm.