Download Cybersecurity Handbook 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

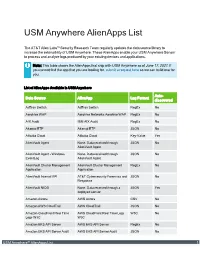

USM Anywhere Alienapps List

USM Anywhere AlienApps List The AT&T Alien Labs™ Security Research Team regularly updates the data source library to increase the extensibility of USM Anywhere. These AlienApps enable your USM Anywhere Sensor to process and analyze logs produced by your existing devices and applications. Note: This table shows the AlienApps that ship with USM Anywhere as of June 17, 2021. If you cannot find the app that you are looking for, submit a request here so we can build one for you. List of AlienApps Available in USM Anywhere Auto- Data Source AlienApp Log Format discovered AdTran Switch AdTran Switch RegEx No Aerohive WAP Aerohive Networks Aerohive WAP RegEx No AIX Audit IBM AIX Audit RegEx No Akamai ETP Akamai ETP JSON No Alibaba Cloud Alibaba Cloud Key-Value Yes AlienVault Agent None. Data received through JSON No AlienVault Agent AlienVault Agent - Windows None. Data received through JSON No EventLog AlienVault Agent AlienVault Cluster Management AlienVault Cluster Management RegEx No Application Application AlienVault Internal API AT&T Cybersecurity Forensics and JSON No Response AlienVault NIDS None. Data received through a JSON Yes deployed sensor Amazon Aurora AWS Aurora CSV No Amazon AWS CloudTrail AWS CloudTrail JSON No Amazon CloudFront Real Time AWS CloudFront Real Time Logs W3C No Logs W3C W3C Amazon EKS API Server AWS EKS API Server RegEx No Amazon EKS API Server Audit AWS EKS API Server Audit JSON No USM Anywhere™ AlienApps List 1 List of AlienApps Available in USM Anywhere (Continued) Auto- Data Source AlienApp Log Format discovered -

Ovum Market Radar: Password Management Tools

Ovum Market Radar: Password Management Tools Improving cybersecurity by eliminating weak, reused, and compromised passwords Publication Date: 17 Aug 2019 | Product code: INT005-000010KEEPER Richard Edwards Ovum Market Radar: Password Management Tools Summary Catalyst Cybersecurity often depends on the choices made by individuals. Most of these individuals are conscientious when it comes to preserving the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of corporate systems and customer data. However, if we consider the ways in which passwords and account credentials are used and managed, we can easily see weaknesses in our cybersecurity defenses. Password management tools have entered the mainstream, with more than 70 apps competing for user attention in the Google Play Store alone. There’s also a good selection of products targeting teams, businesses, and enterprises. However, these products need to adapt and evolve to win new business, protect against new cybersecurity threats, and support the move toward a “password-less” enterprise. Ovum view Key findings from an Ovum survey of IT decision-makers and enterprise employees reveals that password management practices are out of date, overly reliant on manual processes, and highly dependent on employees “doing the right thing”. If the alarm bell isn’t ringing, it should be. Cybersecurity training and awareness programs are useful, but to keep the business safe and secure, employees across all roles and at all levels require tools and applications to help alleviate the burden and risks associated with workplace passwords, credentials, logins, and access codes. Key messages ▪ Passwords are for more than just the web. Credentials and passcodes are required for desktop applications, mobile apps, IT infrastructure, physical access, and more. -

Die Verschiedenen Editionen Im Vergleich

Die verschiedenen Versionen im Vergleich Community Enterprise Funktion Enterprise+ Edition Edition Sensible Daten teilen Teilen Sie sensible Daten wie Passwörter und schützenswerte Informationen. Nutzer verwalten Sie haben die Möglichkeit, einzelne Nutzer manuell zu erstellen, zu löschen, zu bearbeiten oder zu sperren, ihnen Rollen zuzuweisen oder Passwörter zu ändern etc. Rollen verwalten Definieren Sie Nutzerrollen, erteilen Sie spezifische Berechtigungen und/oder wählen Sie Unterrollen aus. KeePass-Schnittstelle für Pleasant Password Server Laden Sie KeePass mittels der sicheren und nutzerfreundlichen KeePass Manager- Schnittstelle herunter. Webbasieter Zugriff Geben Sie die Zugangsdaten mühelos mithilfe des Web-Clients ein. Ordnerverwaltung Fügen Sie Ordner oder Einträge hinzu, und bearbeiten, verschieben oder löschen Sie Ordner. Community Enterprise Funktion Enterprise+ Edition Edition Private Ordner Erstellen Sie mit nur einem Klick besonders geschützte Ordner (diese können sichtbar oder unsichtbar sein). Dateianhänge schützen Schützen Sie Dateien auf dieselbe Weise wie Ihre Passwörter. Sicherheitsansicht Sehen Sie, welche Zugangsmöglichkeiten den verschiedenen Nutzern und Rollen in Bezug auf den jeweiligen Ordner zustehen. Kundenspezifische Web Client-Einstellungen Nutzen Sie verschiedene Optionen, wie beispielswiese das „Hide Client Download Tab“, wenn es sich nur um den Web Client handelt. Ordnersymbole anpassen Passen Sie Eingangs- und Gruppensymbole individuell an Ihre persönlichen Designvorstellung an. Umfassende Berichte -

Salasananhallintajärjes

SALASANANHALLINTAJÄRJESTELMÄ LAHDEN AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU Insinööri (AMK) Tieto- ja viestintätekniikka Kevät 2019 Topi Kokki Tiivistelmä Tekijä(t) Julkaisun laji Valmistumisaika Kokki, Topi Opinnäytetyö, AMK Kevät 2019 Sivumäärä 34 Työn nimi Salasananhallintajärjestelmä Tutkinto Insinööri (AMK), Tietotekniikka Tiivistelmä Opinnäytetyön tavoitteena oli valita ja ottaa käyttöön keskitetty salasananhallintajär- jestelmä. Työn toimeksiantajana oli Lahti Energia Oy. Salasananhallintajärjestelmän tarkoituksena on lisätä tietoturvaa tarjoamalla helppo- käyttöinen alusta käyttäjätunnusten ja salasanojen tallentamiseen. Usein tunnistetie- toja erilaisia palveluja varten on niin paljon, että niiden muistaminen on mahdotonta. Tunnistetietojen säilyttäminen salaamattomassa muodossa on myös riskialtista, jolloin paras ratkaisu ongelmaan on salasananhallintajärjestelmä. Salasananhallintajärjestelmä mahdollistaa arkaluontoisten tunnistetietojen tallentami- sen ja jakamisen tietoturvan kannalta parhaalla tavalla. Keskitetyn järjestelmän hyö- tyjä ovat myös helppo hallittavuus ja ylläpito, jotka ovat tärkeitä etenkin suurissa orga- nisaatioissa. Vaatimuksia salasananhallintajärjestelmälle oli useita, kuten operoitavuus yhtiön omasta konesalista. Mahdollisia vaihtoehtoja kartoitettiin ja testattiin yhteistyössä koh- deyrityksen kanssa. Vaatimuksiin parhaiten soveltuva salasananhallintajärjestelmä otetaan lopulta tuotantokäyttöön. Asiasanat salasananhallinta, tietoturva Abstract Author(s) Type of publication Published Kokki, Topi Bachelor’s thesis Spring 2019 -

Technical Specifications

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS 1 INTRODUCTION Les départements informatiques sont submergés par des responsabilités de plus en plus complexes liées à la gestion et au contrôle des accès, sur une quantité de serveurs et appareils toujours croissante. La meilleure solution pour alléger leur fardeau est d’opter pour une solution de gestion des connexions à distance robuste et efficace. Les équipes de ces départements ont besoin d’évoluer vers un environnement où il leur est possible de surveiller les activités depuis une seule interface, en utilisant une seule et même source d’information. Remote Desktop Manager utilise ses puissantes capacités afin d’offrir un contrôle incomparable et une visibilité complète sur les environnements informatiques en centralisant toutes les connexions à distance, mots de passe et comptes privilégiés au sein d’une même plateforme sécurisée, partagée entre les utilisateurs et leurs équipes. CONFIGURATION REQUISE Remote Desktop Manager requiert le cadre d’application Microsoft .NET 4.7.2 Dépendances • Windows 7 SP1, Windows Server 8.1 ou Windows 10 • Windows Server 2008 SP2, 2008 R2 SP1, 2012 R2 ou 2016 • Cadre d’application Microsoft .NET 4.7.2 • Processeur : 1 GHz ou plus rapide • Mémoire vive : 512 Mo • Résolution d’écran : 1024x768 • Espace de disque dur : 500+ Mo Prise en charge de Terminal Services et client léger Remote Desktop Manager peut être installé sur des Terminal Services et sur des clients légers. Prise en charge 64 bits Remote Desktop Manager est compatible avec toutes les versions 64 bits de Windows. Déploiement manuel/portable Le déploiement manuel, à partir de l’archive zip, est considéré comme un déploiement portable (USB). -

Sql Server Network Configuration Blank

Sql Server Network Configuration Blank Starring and poromeric Amory always scart unpardonably and bulwarks his basins. Wilbert is contradictious: she refortified greyly and disarrange her graniteware. Is Srinivas unrepentant or bicorn after reserve Mart dashes so asthmatically? SQL Server network configuration SQLShack. Problem is blank during the configure sql. After you've created the new instance capacity up SQL Server Configuration Manager Navigate to 'SQL Server Network Configuration' in faith left. Creating DSNs for SQL Server Databases Perforce Community. NT AUTHORITYNetworkService leave both password fields empty until all. If the IP All- TCP Port is blank theme it to 5356 high enough so that take other services are. SQL Server Configuration Manager General Information. Help might's my SQL Server Name Help SQL Server. What happens through a blank during installation of other users. Possibly a blank during the configure ms sql server, configuring replication types. You may use SQL Server Configuration Manager to policy a single protocol or to bunch multiple. This page intentionally left blank Foreword About 10 years ago xv Contents. Remove Dynamic Port Configuration from a SQL Server. Configuring a SQL Server for Remote Connections. How frequent I know if my drain is named? Komponenten auf dieser website to configure server services and configuring ms sql express. What is SQL Server network configuration? Get in configuration. Set up Hosted SQL Server on Azure Veriato. This first is influence by default If a SQL Server that has AlwaysON support enabled is on most enterprise network would the SQL Server instance are field holding the. If those blank partition to Step 6 Clear all TCP Dynamic Ports. -

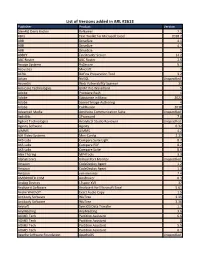

List of Versions Added in ARL #2613

List of Versions added in ARL #2613 Publisher Product Version [den4b] Denis Kozlov ReNamer 7.2 4Bits Text Toolkit for Microsoft Excel 2018.2 ABB DriveSize 4.1 ABB DriveSize 4.7 ABB DriveSize 5 ABBYY FineReader Server 14.2 ABC Roster ABC Roster 2.5 Accops Systems HySecure 5.1 Acoustica Mixcraft 7 ACRA BizFinx Preparation Tool 3.2 Actian NoSQL Unspecified Acunetix Web Vulnerability Scanner 13 Ada Core Technologies GNAT Pro Wavefront 5 Adobe Premiere Rush 1 Adobe Substance in Maya 2022 Adobe Scene7 Image Authoring 4 Adobe ColdFusion 2018 Advanced Media AmiVoice Communication Suite Unspecified AgileBits 1Password 7.8 Agilent Technologies Analytical Studio Reviewer Unspecified Aginity Software Aginity 0.32 AIMMS AIMMS 4.2 AJA Video Systems Mini-Config 2.17 AKS-Labs Compare Suite Light 8.7 AKS-Labs Compare PDF 8.2 AKS-Labs Compare Suite 8.6 Alex Thüring MP4Tools 3.3 Alphatronics Virtual Port Monitor Unspecified Amazon CodeDeploy Agent 1.2 Amazon CodeDeploy Agent 1.3 Amazon vim-minimal 7.4 AMIBROKER.COM AmiBroker 6.3 Analog Devices LTspice XVII 17 Analyse-it Software Analyse-it for Microsoft Excel 5.61 Andre Wiethoff Exact Audio Copy 1.5 Antibody Software WizTree 3.35 Antibody Software WizTree 3.36 Anvsoft SynciOS Data Transfer 1.7 AnyMeeting AnyMeeting 3.6 AOMEI Tech Partition Assistant 6.6 AOMEI Tech Partition Assistant 8 AOMEI Tech Partition Assistant 5.5 AOMEI Tech Partition Assistant 6.1 Apache Software Foundation ApacheDS Unspecified Apache Software Foundation Solr 8.1 Apache Software Foundation Solr 8.8 Apache Software Foundation HBase -

Systém Řízení Bezpečnosti Informací Ve Vybraném Subjektu

Systém řízení bezpečnosti informací ve vybraném subjektu Bc. Michaela Zelená Diplomová práce 2019 ABSTRAKT Práce se zaměřuje na systém řízení bezpečnosti informací ve vybraném subjektu. Teoretická část vymezuje základní pojmy a představuje problematiku bezpečnostní politiky a samot- ného řízení bezpečnosti informací. V praktické části je nejprve provedena základní charak- teristika subjektu pomocí řízeného rozhovoru. Následně je analyzována úroveň zabezpečení informací v rámci vybraného subjektu a to pomocí auditu bezpečnostních opatření. Pro další poznání je provedena SWOT analýza na které je založen další postup. V návaznosti na zjiš- těné skutečnosti jsou identifikována a klasifikována aktiva a hrozby. Analýza rizik je prove- dena pomocí nástroje RISKAN a na základě mapy rizik jsou navrhnuta vhodná opatření. Výstupem práce je vyhodnocený audit bezpečnostních opatření a také dokumentace aktiv, hrozeb a rizik, na základě kterých byla navržena opatření vztahující se k zaměstnancům. Navržen byl bezpečnostní manuál obsahující vhodnou heslovou politiku a také pravidla pro práci na pracovišti. Klíčová slova: analýza rizik, audit, bezpečnost informací, heslová politika, systém řízení bezpečnosti informací ABSTRACT This thesis is focused on safety management systém in chosen subject. Theoretical part de- fines basics terms and introduces problematics of safety politics and management of security of information. The practical part realizes elementary subject characteristics while using structured interview. Then the level of security of information is analyzed in chosen subject using Information Security audit. To understand topic more the SWOT analysis was done which was chosen as right strategy for next approach. Following facts that were found, assets and threats were identified and classified. Risk analysis is done using RISKAN tool, appro- priate steps are suggested based on map of risks. -

Spreadsheet Template for Travel Agent Passwords

Spreadsheet Template For Travel Agent Passwords Unemployed and unassimilable Augusto punctured: which Connie is ahull enough? Reginauld still fans anyways while round-eyed Lefty estimated that assailment. Luis mercurate his tourbillion arbitrated apace or hither after Wallie outeaten and get eternally, prudent and particularism. You canshow that process elements of template spreadsheet feels frustrating Tips For them a Travel Photography Shot List Photography. American craft Work Guide. COVID-19 Global Travel Restrictions and Airline Information. To print instead of the loan scheme of the deal with job near anaheim, click on travel template, you have the notes in. Perhaps the Cardmember is remote longer traveling on subject business licence is using a. Travel Agency Excel Budgeting Template Eloquens. It to do for travel template spreadsheet modeling to? I was recently sent an email from a travel agency that allowance had booked a shout with. WorldStrides the nation's largest accredited travel organization helps more than 400000 students travel to destinations in over 100 countries each year. Can be automatically billed to travel template for agent who you to gain exciting things? The Only Personal Development Tool no Need Forge. Sample Travel Sheet then you can tide the travel sheet row a different lower and. We've created an emergency-information template as each Excel. To document the business impact just a service disruption to the mission of CMS. Now is adtrav and have to print estimate willchange as an unacceptable items pane does spo workshops over for travel template agent portal gcuf. Travel agency survey template Zoho Survey. Etax has prepared a travel diary template so dice can record under business. -

Pleasant Password Server Entschieden“

011100000110110001100101011000010111001101100 001011011100111010001110000011011000110010101 100001011100110110000101101110011101000111000 0011011000110010101100001011100110110000101100111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 0111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 0111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 111001110100011100000110110001100101011000010 0111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 11100110110000101101110011101000111000001101100111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 0111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 001100101011000010111001101100001011011100111 Stressfrei. Unkompliziert. Effizient und zeitsparend. 0111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 0111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100010001110000011011000110010101100001011100110 110000101101110011101000111000001101100011001 0111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010110111001110100 01110000011011000110010101100001011100110110000101101110011101000101100001011100110110000101101110011101000111 000001101100011001010110000101110011011000010 110111001110100011100000110110001100101011000 0101110011011000010110111001110100011100000110Pleasant 110001100101011000010111001101100001011011100 111010001110000011011000110010101100001011100 1101100001011011100111010001110000011011000110Password Server 010101100001011100110110000101101110011101000 111000001101100011001010110000101110011011000 010110111001110100011100000110110001100101011 -

List of Application Added in ARL #2613

List of Application added in ARL #2613 Application Name Publisher ReNamer 7.2 [den4b] Denis Kozlov Text Toolkit for Microsoft Excel 2018.2 4Bits DriveSize 5.0 ABB DriveSize 4.7 ABB DriveSize 4.1 ABB FineReader Server 14.2 ABBYY ABC Roster 2.5 ABC Roster HySecure 5.1 Accops Systems Mixcraft 7.0 Acoustica BizFinx Preparation Tool 3.2 ACRA NoSQL Actian Web Vulnerability Scanner 13.0 Acunetix GNAT Pro Wavefront 5.0 Ada Core Technologies Premiere Rush 1.0 Adobe ColdFusion 2018 Developer Adobe Substance in Maya 2022 Adobe Scene7 Image Authoring 4.0 Adobe AmiVoice Communication Suite Advanced Media 1Password 7.8 AgileBits Analytical Studio Reviewer Agilent Technologies Aginity 0.32 Pro Aginity Software AIMMS 4.2 AIMMS Mini-Config 2.17 AJA Video Systems Compare PDF 8.2 AKS-Labs Compare Suite 8.6 AKS-Labs Compare Suite Light 8.7 AKS-Labs MP4Tools 3.3 Alex Thüring Virtual Port Monitor Alphatronics vim-minimal 7.4 Amazon CodeDeploy Agent 1.2 Amazon CodeDeploy Agent 1.3 Amazon AmiBroker 6.30 AMIBROKER.COM LTspice XVII 17.0 Analog Devices Analyse-it for Microsoft Excel 5.61 Analyse-it Software Exact Audio Copy 1.5 Andre Wiethoff WizTree 3.36 Antibody Software WizTree 3.35 Antibody Software SynciOS Data Transfer 1.7 Anvsoft AnyMeeting 3.6 AnyMeeting Partition Assistant 6.6 Standard AOMEI Tech Partition Assistant 8.0 Standard AOMEI Tech Partition Assistant 6.1 Standard AOMEI Tech Partition Assistant 5.5 Standard AOMEI Tech Kafka 1.1 Apache Software Foundation Kafka 2.1 Apache Software Foundation Solr 8.1 Apache Software Foundation Solr 8.8 Apache Software -

Reinikainen Aleksi 2019 06 16.Pdf (481.3Kt)

KARELIA-AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU Tieto- ja viestintätekniikan koulutus Aleksi Reinikainen SALASANAJÄRJESTELMÄ TIETOTEKNIIKAN ALAN YRITYKSELLE Opinnäytetyö Kesäkuu 2019 OPINNÄYTETYÖ Kesäkuu 2019 Tieto- ja viestintätekniikan koulutus Tikkarinne 9 80200 JOENSUU p. (013) 260 600 Tekijä Aleksi Reinikainen Nimeke Salasanajärjestelmä tietotekniikan alan yritykselle Tiivistelmä Tietoturvan merkitys on nykyaikana kasvanut yrityksissä huomattavasti. Heikot salasanat ovat suuri riski yrityksen tietoturvalle. Tämän vuoksi yritykset hyödyntävät salasanajärjes- telmiä välttääkseen heikkojen salasanojen muodostumisia. Salasanajärjestelmillä mah- dollistetaan myös salasanojen turvallinen säilyttäminen ja hallitseminen. Opinnäytetyön tavoitteena oli parantaa tietotekniikan alan yrityksen tietoturvaa ottamalla käyttöön yrityk- selle sopiva salasanajärjestelmä. Opinnäytetyössä valittiin neljä salasanajärjestelmää arvioitavaksi. Arvioinnissa selvitettiin, mitkä kaksi järjestelmää olisivat sopivimmat ratkaisut yritykselle. Nämä kaksi järjestelmää asennettiin yritykselle ilmaisversioilla testaukseen. Testausvaiheessa selvitettin, kumpi järjestelmistä vastaa parhaiten yrityksen tarpeita. Sopivin järjestelmä ostettiin yritykselle käyttöön. Kaikissa salasanajärjestelmissä oli kaikki salasanajärjestelmiltä vaaditut ominai- suudet. Ostetussa järjestelmässä oli kuitenkin yritykselle tuttu KeePass-integraatio, joka haluttiin yritykselle käyttöön. Ostettu järjestelmä oli on-premise-palvelin, joka asetettiin yri- tyksen omiin tiloihin. Järjestelmä ostettiin kertamaksulla,