You, Patroclus: the Effect of the Apostrophe on the Sympathetic Reception of Patroclus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

1 Achilles and Patroclus in the Trojan War: an Introductory Case Study

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89582-8 - Interpreting the Images of Greek Myths: An Introduction Klaus Junker Excerpt More information 1 Achilles and Patroclus in the Trojan War: An introductory case study From early times, the use of the bow and arrow formed a part of Greek military practice, as a dangerous long-range weapon. If the arrow had not struck an immediately fatal blow, it could still be the cause of insidious wounds. If the arrowhead had become completely embedded in the body and perhaps, in the heat of the battle, broken off from the shaft, then the removal of the metal would cause acute pain and, in certain circumstances, cause further damage to the tissues surrounding the wound. In the detailed battle descriptions of the Iliad, wounds caused by arrows are mentioned on various occasions. When the Greek Menelaus has just been struck by an arrow, his initial fear gives way to relief that the binding, which attaches the arrowhead to the shaft, is still visible (4, 150–1): the wound cannot be deep and the damage is therefore slight. So too in the picture that will now be used as a test case for interpretation (Fig. 1), the warrior has been lucky in his misfortune. The arrow portrayed in beautiful detail in the left foreground, so as to put the cause of the wound in his arm beyond all doubt, is still complete and, at the most, slightly bent at the tip, unless the small irregularity in the drawing is unintentional. Yet the abrupt turn away of the head and the open mouth, with the teeth visible and coated in added white, convey something of the pain that the man feels, as his comrade-in-arms applies the bandage to his arm. -

SOPHOCLES' AJAX, a Translation by Dennis Daly

Wilderness House Literary Review 6/4 Dennis Daly SOPHOCLES’ AJAX ©2012 Dennis Daly Introduction Sophocles lived during the golden age of ancient Greece. He was born around 496 BC in Colonus, just outside of Athens, and died 90 years later. He probably came from a wealthy merchant family and lived what many would think of as a near perfect life. So the dry facts seem to say. At sixteen years of age Sophocles led the paean, celebrating a decisive Greek victory over the Persians at Salamis. This was more than just an everyday honor. You needed the physique, athleticism, a stage presence and the ability to sing. Sophocles held numerous civic positions of high honor including treasurer, gen- eral (he served with the legendary Pericles), priest, and commissioner. His friends included the great historian Herodotus. Of all of Sophocles’ 123 plays only seven survive. They are Oedipus Rex, Antigone, Oedipus at Colonus, Electra, Women of Trachis, Philoctetes, and Ajax. Sophocles wrote his plays specifically as entries for the Dionysia festivals held annually in Athens. Playwrights usually entered four plays at a time into these competitions. The so-called Theban plays of Sophocles, Oedipus Rex, Antigone, and Oedipus at Colonus, were never entered together, but were each entered with another set of plays. Early on Sophocles bested his older rival Aeschylus and never looked back winning many more competitions than either Aeschylus or his young- er rival, Euripides. The power of these tragedies and their subject matter belie the official biogra- phy of Sophocles. The dramatist simply understood shame, degradation, alien- ation, despair and madness a little too well. -

The Iliad Book 1 Lines 1-487

The Iliad Book 1 lines 1-487. Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0134:book=1:card=1 [1] The wrath sing, goddess, of Peleus' son, Achilles, that destructive wrath which brought countless woes upon the Achaeans, and sent forth to Hades many valiant souls of heroes, and made them themselves spoil for dogs and every bird; thus the plan of Zeus came to fulfillment, from the time when first they parted in strife Atreus' son, king of men, and brilliant Achilles. [8] Who then of the gods was it that brought these two together to contend? The son of Leto and Zeus; for he in anger against the king roused throughout the host an evil pestilence, and the people began to perish, because upon the priest Chryses the son of Atreus had wrought dishonour. For he had come to the swift ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, bearing ransom past counting; and in his hands he held the wreaths of Apollo who strikes from afar, on a staff of gold; and he implored all the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, the marshallers of the people: Sons of Atreus, and other well-greaved Achaeans, to you may the gods who have homes upon Olympus grant that you sack the city of Priam, and return safe to your homes; but my dear child release to me, and accept the ransom out of reverence for the son of Zeus, Apollo who strikes from afar. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Homer's Roads Not Taken

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Homer’s Roads Not Taken Stories and Storytelling in the Iliad and Odyssey A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Craig Morrison Russell 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Homer’s Roads Not Taken Stories and Storytelling in the Iliad and Odyssey by Craig Morrison Russell Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Alex C. Purves, Chair This dissertation is a consideration of how narratives in the Iliad and Odyssey find their shapes. Applying insights from scholars working in the fields of narratology and oral poetics, I consider moments in Homeric epic when characters make stories out of their lives and tell them to each other. My focus is on the concept of “creativity” — the extent to which the poet and his characters create and alter the reality in which they live by controlling the shape of the reality they mould in their storytelling. The first two chapters each examine storytelling by internal characters. In the first chapter I read Achilles’ and Agamemnon’s quarrel as a set of competing attempts to create the authoritative narrative of the situation the Achaeans find themselves in, and Achilles’ retelling of the quarrel to Thetis as part of the move towards the acceptance of his version over that of Agamemnon or even the Homeric Narrator that occurs over the course of the epic. In the second chapter I consider the constant storytelling that [ii ] occurs at the end of the Odyssey as a competition between the families of Odysseus and the suitors to control the narrative that will be created out of Odysseus’s homecoming. -

Llt 121 Classical Mythology Lecture 36 Good Morning

LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY LECTURE 36 GOOD MORNING AND WELCOME TO LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY IN WHICH WE TAKE UP PROBABLY THE SECOND OLDEST STORY IN THE BOOK, THE SECOND OLDEST GREAT EPIC IN WESTERN LITERATURE, THE ILIAD OF HOMER. THE GILGAMESH EPIC OF THE VARIOUS MESOPOTAMIAN PEOPLE IS OLDER. THIS IS NUMBER TWO. IT TRIES HARDER. WHEN LAST WE LEFT OFF ACHILLES WAS STILL POUTING BY THE SIDE OF HIS SWIFT, BLACK SHIPS WITH HIS FRIEND PATROCLUS. YOU WILL REMEMBER THAT ACHILLES HAS ALREADY TURNED DOWN ONE OFFER FROM AGAMEMNON FOR A COMPLETE APOLOGY, BRISEIS BACK, VALUABLE PRIZES, THE WHOLE NINE YARDS. JUST COME BACK TO US ACHILLES. WE NEED YOU. ACHILLES SAYS I'VE GOT TWO POSSIBLE FATES. ONE, I CAN DIE IN BATTLE, WIN LOTS OF GLORY, AND BE FAMOUS FOREVER AFTER. OR B, I COULD LIVE TO A LONG, GREAT OLD AGE, BE REAL HAPPY AND LEAVE BEHIND NO ARITAE OR VIRTUE AND HAVE NO KLEOS OR FAME AFTER MY DEATH. I MIGHT SAY NUMBER TWO IS LOOKING BETTER. SO THE GREEKS GET THEIR BUTTS KICKED FOR ANOTHER THREE OR FOUR BOOKS. FINALLY, NESTOR THE 300 YEAR OLD GUY WHO TALKS JUST ABOUT FOREVER COMES UP WITH AN IDEA FOR PATROCLUS. PATROCLUS, I'M GOING TO TRY TO PERSUADE YOU TO PUT ON THE ARMOR OF ACHILLES AND GO INTO BATTLE. PATROCLUS FINALLY AGREES TO GET NESTOR TO SHUT UP AND ALSO MAYBE IT'S NOT EASY TO BE GILLIGAN, SCOTTIE PIPPIN, OR ED MCMAHON, THE NUMBER TWO BANANA. YOU WANT TO.STAND IN THE LIMELIGHT AND DO A FEW OF THOSE ON PUBLISHERS CLEARINGHOUSE SWEEPSTAKES COMMERCIALS OF YOUR OWN. -

Helen of Troy: She Was Not a Dumb Blonde

HELEN OF TROY A HEROINE IN A MAN’S WORLD! Katerina Ladianou, Classics, OSU Helen is a beautiful woman, some say a Goddess, others say a whore because of her adulterous ways, and she is pursued relentlessly by suitors from all over the ancient world. Homer, Euripides, and Stesichorus all narrate her story, but Homer is the original source in his 2 epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The fairest woman in the world is Helen, the daughter of the King of Sparta Tyndareos and his wife Leda. Their other daughter Clytemnestra is married to Agamemnon. Such is the fame of the beauty of Helen that every young prince craves to marry her. Superhero Theseus abducts her first, but her brothers Castor and Pollux, [both Argonauts, who sailed to Colchis through the Hellespont with Jason on the Ship Argo to get the Golden Fleece], get her back home. So, when suitors from all over Greece assemble in Sparta to ask for her hand, her father Tyndareos, fearing another abduction makes them take an oath to defend whomever he chooses for her husband, and, moreover, that they collectively would punish anyone who tried to abduct Helen. Then Tyndareos chooses Menelaos and he makes him King of Sparta. In the meantime, Goddess Aphrodite sends an image of Helen to Paris of Troy who at the time is out in the fields shepherding his father’s goats; he falls madly in love with Helen, and the rest is history, for love is the strongest force in the whole world! In the Iliad, Paris, a prince of Troy, a city that has accumulated enormous wealth by controlling the flow of merchant shipping through the nearby Hellespont [in what is now NW Turkey; the Dardanelles], abducts Helen. -

The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs

The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs: Foundational Texts Compared Edited by Fritz-Heiner Mutschler The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs: Foundational Texts Compared Edited by Fritz-Heiner Mutschler This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Fritz-Heiner Mutschler and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0400-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0400-4 Contents Acknowledgments vii Conventions and Abbreviations ix Notes on Contributors xi Introduction 1 PART I. THE HISTORY OF THE TEXTS AND OF THEIR RECEPTION A. Coming into Being 1. The Formation of the Homeric Epics 15 Margalit FINKELBERG 2. The Formation of the Classic of Poetry 39 Martin KERN 3. Comparing the Comings into Being of Homeric Epic and the Shijing 73 Alexander BEECROFT B. “Philological” Reception 1. Homeric Scholarship in its Formative Stages 87 Barbara GRAZIOSI 2. Odes Scholarship in its Formative Stage 117 Achim MITTAG 3. The Beginning of Scholarship in Homeric Epic and the Odes: a Comparison 149 GAO Fengfeng / LIU Chun C. Cultural Role 1. Homer in Greek Culture from the Archaic to the Hellenistic Period 163 Glenn W. -

Achilles in the Underworld: Iliad, Odyssey, and Aethiopis Anthony T

EDWARDS, ANTHONY T., Achilles in the Underworld: "Iliad, Odyssey", and "Aethiopis" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 26:3 (1985:Autumn) p.215 Achilles in the Underworld: Iliad, Odyssey, and Aethiopis Anthony T. Edwards I HE ACTION of Arctinus' Aethiopis followed immediately upon T the Iliad in the cycle of epics narrating the war at Troy. Its central events were the combat between Achilles and the Ama zon queen Penthesilea, Achilles' murder of Thersites and subsequent purification, and Achilles' victory over the Ethiopian Memnon, lead ing to his own death at the hands of Apollo and Paris. In his outline of the Aethiopis, Proclus summarizes its penultimate episode as fol lows: "Thetis, arriving with the Muses and her sisters, mourns her son~ and after this, snatching (allap1Tauao-a) her son from his pyre, Thetis carries him away to the White Island (AevK7) "1iuo~)." Thetis removes, or 'translates', Achilles to a distant land-an equivalent to Elysium or the Isles of the Blessed - where he will enjoy eternally an existence similar to that of the gods.! Unlike the Aethiopis, the Iliad presents no alternative to Hades' realm, not even for its hero: Achil les, who has learned his fate from his mother (9.410-16),foresees his arrival there (23.243-48); and in numerous references elsewhere to Achilles' death, the Iliad never arouses any alternative expectation.2 1 For Proclus' summary see T. W. Allen, ed., Homeri Opera V (Oxford 1946) 105f, esp. 106.12-15. On the identity of the AEVKT, ~(J'o<; with Elysium and the Isles of the Blessed see E. -

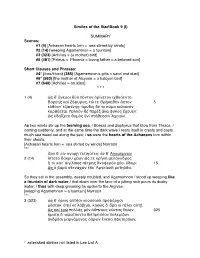

* Asterisked Similes Not Listed in Lee List a Similes of the Iliad Book 9 (Ι) SUMMARY Scenes: #1 (4) [Achaean Hearts Torn ≈

Similes of the Iliad Book 9 (Ι) SUMMARY Scenes: #1 (4) [Achaean hearts torn ≈ sea stirred by winds] #2 (14) [weeping Agamemnon ≈ a fountain] #3 (323) [Achilles ≈ (a mother) bird] #5 (481) [Peleus > Phoenix ≈ loving father > a beloved son] Short Clauses and Phrases: #4* (ὅσα/τόσα) (385) [Agamemnon’s gifts ≈ sand and dust] #6* (563) [the mother of Alcyone ≈ a halcyon bird] #7 (648) [Achilles ≈ an alien] * * * 1 (4) ὡς δ᾽ ἄνεμοι δύο πόντον ὀρίνετον ἰχθυόεντα Βορέης καὶ Ζέφυρος, τώ τε Θρῄκηθεν ἄητον 5 ἐλθόντ᾽ ἐξαπίνης: ἄμυδις δέ τε κῦμα κελαινὸν κορθύεται, πολλὸν δὲ παρὲξ ἅλα φῦκος ἔχευεν: ὣς ἐδαΐζετο θυμὸς ἐνὶ στήθεσσιν Ἀχαιῶν. As two winds stir up the teeming sea, / Boreas and Zephyrus that blow from Thrace, / coming suddenly, and at the same time the dark wave / rears itself in crests and casts much sea weed out along the sea; / so were the hearts of the Achaeans torn within their chests. [Achaean hearts torn ≈ sea stirred by winds] Narrator *** ἷζον δ᾽ εἰν ἀγορῇ τετιηότες: ἂν δ᾽ Ἀγαμέμνων 2 (14) ἵστατο δάκρυ χέων ὥς τε κρήνη μελάνυδρος ἥ τε κατ᾽ αἰγίλιπος πέτρης δνοφερὸν χέει ὕδωρ: 15 ὣς ὃ βαρὺ στενάχων ἔπε᾽ Ἀργείοισι μετηύδα. So they sat in the assembly, deeply troubled, and Agamemnon / stood up weeping like a fountain of dark water / that down over the face of a jutting rock pours its dusky water; / thus with deep groaning he spoke to the Argives. [weeping Agamemnon ≈ a fountain] Narrator *** 3 (323) ὡς δ᾽ ὄρνις ἀπτῆσι νεοσσοῖσι προφέρῃσι μάστακ᾽ ἐπεί κε λάβῃσι, κακῶς δ᾽ ἄρα οἱ πέλει αὐτῇ, ὣς καὶ ἐγὼ πολλὰς μὲν ἀΰπνους νύκτας ἴαυον, 325 ἤματα δ᾽ αἱματόεντα διέπρησσον πολεμίζων ἀνδράσι μαρνάμενος ὀάρων ἕνεκα σφετεράων. -

Troy Myth and Reality

Part 1 Large print exhibition text Troy myth and reality Please do not remove from the exhibition This two-part guide provides all the exhibition text in large print. There are further resources available for blind and partially sighted people: Audio described tours for blind and partially sighted visitors, led by the exhibition curator and a trained audio describer will explore highlight objects from the exhibition. Tours are accompanied by a handling session. Booking is essential (£7.50 members and access companions go free) please contact: Email: [email protected] Telephone: 020 7323 8971 Thursday 12 December 2019 14.00–17.00 and Saturday 11 January 2020 14.00–17.00 1 There is also an object handling desk at the exhibition entrance that is open daily from 11.00 to 16.00. For any queries about access at the British Museum please email [email protected] 2 Sponsor’sThe Trojan statement War For more than a century BP has been providing energy to advance human progress. Today we are delighted to help you learn more about the city of Troy through extraordinary artefacts and works of art, inspired by the stories of the Trojan War. Explore the myth, archaeology and legacy of this legendary city. BP believes that access to arts and culture helps to build a more inspired and creative society. That’s why, through 23 years of partnership with the British Museum, we’ve helped nearly five million people gain a deeper understanding of world cultures with BP exhibitions, displays and performances. Our support for the arts forms part of our wider contribution to UK society and we hope you enjoy this exhibition. -

Sing, Goddess, Sing of the Rage of Achilles, Son of Peleus—

Homer, Iliad Excerpts 1 HOMER, ILIAD TRANSLATION BY IAN JOHNSTON Dr. D’s note: These are excerpts from the complete text of Johnston’s translation, available here. The full site shows original line numbers, and has some explanatory notes, and you should use it if you use this material for one of your written topics. Book I: The quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon begins The Greeks have been waging war against Troy and its allies for 10 years, and in raids against smaller allies, have already won war prizes including women like Chryseis and Achilles’ girl, Briseis. Sing, Goddess, sing of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus— that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans to countless agonies and threw many warrior souls deep into Hades, leaving their dead bodies carrion food for dogs and birds— all in fulfilment of the will of Zeus. Start at the point where Agamemnon, son of Atreus, that king of men, quarrelled with noble Achilles. Which of the gods incited these two men to fight? That god was Apollo, son of Zeus and Leto. Angry with Agamemnon, he cast plague down onto the troops—deadly infectious evil. For Agamemnon had dishonoured the god’s priest, Chryses, who’d come to the ships to find his daughter, Chryseis, bringing with him a huge ransom. In his hand he held up on a golden staff the scarf sacred to archer god Apollo. He begged Achaeans, above all the army’s leaders, the two sons of Atreus: “Menelaus, Agamemnon, sons of Atreus, all you well-armed Achaeans, may the gods on Olympus grant you wipe out Priam’s city, and then return home safe and sound.