{PDF EPUB} the Pools of Silence by Henry De Vere Stacpoole Chapter 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chunga 12 I Learned That Mike Glicksohn and It Is a Pleasure to See Them Again

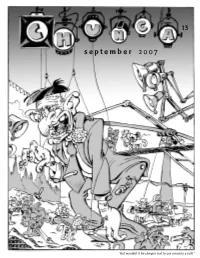

13 s e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 7 “But wouldn’t it be cheaper just to use a man in a suit?” Chunga is a darkened theater where Lee Hoffman and Ron Bennett sit in the middle third row. Rich brown leans forward in the row behind them, and he won’t stop talking. Other fans are expected, and all three look over their shoulders in anticipation. In the projection booth, Bob Tucker is pouring shots from a green-labeled bottle. One for each reel change — two cartoons, a news reel, the serial chapter, the A picture, and the B picture. A pleasant odor of bourbon and popcorn fills the darkness as he throws the switch. Available by editorial whim or wistfulness, or, grudgingly, for $3.50 for a single issue; PDFs of every issue may be found at eFanzines.com. Edited by Andy ([email protected]), Randy ([email protected]), and carl ([email protected]). Please address all postal correspondence to 1013 North 36th Street, Seattle WA 98103. Editors: please send three copies of any zine for trade. In this issue . The Ascent of Hokum Art Credits A premonitory caution . 1 in order of first appearance Terminal Eyes Marc Schirmeister front cover by Andy Hooper . 2 William Rotsler 3, 26 Take the Hokum and Run (Celluloid Fantasia reprints) Stu Shiffman 7, 9, 10 by Stu Shiffman . 5 Ken Fletcher 12, 14, 15 Woody Guthrie, the Singing Sidekick by Stu Shiffman . 6 Ian Gunn 14 The Most Monstrous Show on Earth! Michael Dobson 15 (bottom), from by Bob Webber . -

Shipwrecked Six Pack Ndash; Robinson Crusoe, Gulliverrsquo;S

dsVSC (Download) Shipwrecked Six Pack ndash; Robinson Crusoe, Gulliverrsquo;s Travels, The Swiss Family Robinson, The Coral Island, Treasure Island and The Blue Lagoon (Illustrated) (Six Pack Classics Book 2) Online [dsVSC.ebook] Shipwrecked Six Pack ndash; Robinson Crusoe, Gulliverrsquo;s Travels, The Swiss Family Robinson, The Coral Island, Treasure Island and The Blue Lagoon (Illustrated) (Six Pack Classics Book 2) Pdf Free R. M. Ballantyne, Daniel Defoe, Henry De Vere Stacpoole, Robert Louis Stevenson, Jonathan Swift, Johann David Wyss ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #91644 in eBooks 2015-11-19 2015-11-19File Name: B0189QRNOM | File size: 45.Mb R. M. Ballantyne, Daniel Defoe, Henry De Vere Stacpoole, Robert Louis Stevenson, Jonathan Swift, Johann David Wyss : Shipwrecked Six Pack ndash; Robinson Crusoe, Gulliverrsquo;s Travels, The Swiss Family Robinson, The Coral Island, Treasure Island and The Blue Lagoon (Illustrated) (Six Pack Classics Book 2) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Shipwrecked Six Pack ndash; Robinson Crusoe, Gulliverrsquo;s Travels, The Swiss Family Robinson, The Coral Island, Treasure Island and The Blue Lagoon (Illustrated) (Six Pack Classics Book 2): 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Illustrated Classics on the Cheap - I Love it!By Don KidwellThought I'd browse (once again) and see what illustrated classics could be had for a song and pass it on. Short of grabbing the freebies put together by a group of volunteers (always an iffy proposal as to quality) you could easily spend a buck or more per title on this grouping if purchased separately, or save yourself the time, trouble and expense by grabbing this collection of classics with both an active table of contents and a nifty image gallery including first edition title pages, fine engravings, author portraits and more. -

December 2019 Program Highlights

DECEMBER 2019 HDNET MOVIES showcases the best in box office hits, award-winning films and memorable movie PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS marathons, uncut and commercial free! MAKE MY DAY MARATHON BLUE LAGOON DOUBLE SATURDAY, DECEMBER 7 ALL DAY SUNDAY, DECEMBER 1 9pmET Do you feel lucky? Well you should! Tune-in to HDNET This December don’t get deserted on an island, just tune-in MOVIES on Saturday, December 7 for a line-up Clint to HDNET MOVIES for a Blue Lagoon double. Catch himself would approve of, all five DIRTY HARRY Movies! Brooke Shields and Christopher Atkins in THE BLUE Want to keep the luck going? Then don’t miss the re-air of LAGOON followed by Milla Jovovich and Brian Krause in the awesome marathon on Christmas Day! the sequel RETURN TO THE BLUE LAGOON. BORN ON THE FOURTH OF JULY NAUGHTY OR NICE FRIDAY, DECEMBER 20 9pmET DECEMBER 22 – 24 Tom Cruise stars as Ron Kovic, a paralyzed Vietnam War ‘Tis the season and HDNET MOVIES wants to know if you Veteran who becomes an anti-war and pro-human rights have been naughty or nice?! Don’t miss the Naughty or activist after feeling betrayed by the country he fought for. Nice movie marathon featuring SHOWGIRLS, SECRETARY, Tune-in for a special airing of BORN ON THE FOURTH OF BREATHLESS, KILLING ME SOFTLY, ELEKTRA LUXX, JULY on the 30th Anniversary of the film’s release. SPREAD and LADY CHATTERLEY'S LOVER. NON-STOP NORRIS THAT OLD FEELING THE AVIATOR ONCE UPON A TIME IN SUNDAY, DECEMBER 29 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 1 TUESDAY, DECEMBER 3 THE WEST 7:30pmET 7:10pmET 6:05pmET MONDAY, DECEMBER 9 9pmET Time waits for no man, unless that A bride’s divorced parents discover Leonardo DiCaprio stars in this man is Chuck Norris! Tune-in to their old feelings for each other Martin Scorsese directed Sergio Leone's epic western about HDNET MOVIES this December for during her wedding. -

THE BLUE LAGOON A.K.A

THE BLUE LAGOON a.k.a. Sandown Canoe Lake By Dave Bambrough (Part one) Development of the ground east of the Old Coastguard Station in Culver Road had begun with the opening of Sandham Grounds in 1924. It had transformed part of this area from a wilderness into an array of beauty. Further enhancement was about to be constructed by private enterprise by way of a boating lake, right next door to the Grounds. Rumours of a Canoe Lake for Sandown were rife in the year of 1928. The success of similar ventures at Ryde and Southsea had strengthened the claims of those responsible for providing more entertainment for the visiting children to the Island. The majority of these came from London between Easter and the beginning of July, which greatly helped the local economy over this rather quiet period. Competition from Shanklin had been strengthened that year with the opening of Fairy Court House, which had been presented to the School Journey Association specifically for the use as a hostel for visiting children from London. The selected site for the boating lake was 5 acres of land owned by the War Department adjoining the Sandham Grounds. A meeting was convened between the Chairman of the General Purposes Committee (Mr A.J. Harman), the Chairman of the Sandham Grounds Committee (Mr A. Dutton), with their surveyor and representatives of the promoters of the Canoe Lake. This it was hoped would broker an agreement for submission to the council of the filling in of a ditch that separated the two ventures, the carrying off of the water and a connecting entrance between the two concerns. -

The Blue Lagoon: a Romance

The Blue lagoon: A Romance by H. de Vere Stacpoole Introduction to the Project Gutenberg text of H. de Vere Stacpoole's The Blue Lagoon: A Romance by Edward A. Malone University of Missouri-Rolla Born on April 9, 1863, in Kingstown, Ireland, Henry de Vere Stacpoole grew up in a household dominated by his mother and three older sisters. William C. Stacpoole, a doctor of divinity from Trinity College and headmaster of Kingstown school, died some time before his son's eighth birthday, leaving the responsibility of supporting the family to his Canadian- born wife, Charlotte Augusta Mountjoy Stacpoole. At a young age, Charlotte had been led out of the Canadian backwoods by her widowed mother and taken to Ireland, where their relatives lived. This experience had strengthened her character and prepared her for single parenthood. Charlotte cared passionately for her children and was perhaps overly protective of her son. As a child, Henry suffered from severe respiratory problems, misdiagnosed as chronic bronchitis by his physician, who in the winter of 1871 advised that the boy be taken to Southern France for his health. With her entire family in tow, Charlotte made the long journey from Kingstown to London to Paris, where signs of the Franco-Prussian War were still evident, settling at last in Nice at the Hotel des Iles Britannique. Nice was like paradise to Henry, who marveled at the city's affluence and beauty as he played in the warm sun. After several more excursions to the continent, Stacpoole was sent to Portarlington, a bleak boarding school more than 100 miles from Kingstown. -

LESLEY VANDERWALT Make-Up and Hair Designer

LESLEY VANDERWALT Make-Up And Hair Designer FILM PROMETHEUS 2 Make-Up and Hair Designer Filming Begins April 2016 Director: Ridley Scott 20th Century Fox GODS OF EGYPT Make-Up and Hair Designer Summit Entertainment Director: Alex Proyas MAD MAX: FURY ROAD Make-Up and Hair Designer Village Roadshow Pictures Director: George Miller Winner: Academy Award for Best Make-Up and Hairstyling Winner: BAFTA for Best Make-up and Hair Winner: Critics’ Choice Award for Best Hair & Make-Up Winner: Make-Up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild Awards for Best Period and/or Character Make-Up THE GREAT GATSBY Make-Up and Hair Supervisor – Additional Design Warner Bros. Director: Baz Luhrmann Winner of the M.A.C Austrailia APDG Award for Make-up shared with Kerry Warn and Maritzio Silvi. Nominated for Hollywood Make-up Artists and Hairstylists Guild Award Best Character Make-Up SLEEPING BEAUTY Make-Up and Hair Designer / Make-Up Department Head Magic Films Director: Julia Leigh Cast: Emily Browning, Rachael Blake, Ewen Leslie, Eden Falk, Mirrah Folks, Chris Haywood, Hugh Keays-Byrne, Tammy Macintosh, Tracy Mann, Sarah Snook, Matthew Whittet Winner of the M.A.C Austrailia APDG Award for Make-up KNOWING Make-Up and Hair Designer Summit Entertainment Director: Alex Proyas Cast: Rose Byrne, Ben Mendelsohn AUSTRAILIA Make-Up and Hair Supervisor – Additional Design 20th Century Fox Director: Baz Lurmann Cast: Jack Thompson, Ben Mendelsohn, Jacek Koman, Sandy Gore, Wah Yuen, Ursula Yovich, GHOST RIDER Make-Up and Hair Designer Columbia Pictures Director: Mark Stephan -

The Many Faces of Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe: Examining the Crusoe Myth in Film and on Television

THE MANY FACES OF DANIEL DEFOE'S ROBINSON CRUSOE: EXAMINING THE CRUSOE MYTH IN FILM AND ON TELEVISION A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by SOPHIA NIKOLEISHVILI Dr. Haskell Hinnant, Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE MANY FACES OF DANIEL DEFOE’S ROBINSON CRUSOE: EXAMINING THE CRUSOE MYTH IN FILM AND ON TELEVISION presented by Sophia Nikoleishvili, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Haskell Hinnant Professor George Justice Professor Devoney Looser Professor Catherine Parke Professor Patricia Crown ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of my adviser, Dr. Haskell Hinnant, to whom I would like to express the deepest gratitude. His continual guidance and persistent help have been greatly appreciated. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, Dr. Catherine Parke, Dr. George Justice, Dr. Devoney Looser, and Dr. Patricia Crown for their direction, support, and patience, and for their confidence in me. Their recommendations and suggestions have been invaluable. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...................................................................................................ii INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................1 -

The Movie Database

- 1 - The Movie Database Ellen Munthe-Kaas February 2008 The following is a slightly shorter version in English of a document written in conjunction with the mandatory exercises in INF3100. 1 Background The test database to be used in the mandatory exercises is a version of the Internet Movie Database (imdb) [1], which is a large database containing information on approximately 700000 films and 60000 TV series, 1.7 million persons related to the films, descriptions of the films etc. The database runs on Postgres. History A first version containing a subset of the films was realized in 2002 on Sybase ASE 11.9.2. Later the department migrated to Oracle. In 2007 the department decided to migrate to Postgres; in connection with this we have decided to include a more or less full version of imdb. The students have read access to this 2007 version. They are however to make their own copy of the 2002 version. Notice that the schema of the two versions differ somewhat due to changes in the source files available from imdb. - 2 - 2 Design of the 2002 Version Figure 1: The 2002 database The database is centered around three entity types – films, persons, and participation which links the first two together. The ORM-UML diagram can be seen in Figure 1. Each concept in an ORM-UML model translates into a table during the realization stage. Not all concepts warrant a table, and in this particular case Country, Language, Rating, Votes, Year, Title, Name, and Gender have been suppressed. The resulting tables are as follows: AlternativeFilmTitle, Film, FilmCountry, FilmGenre, FilmLanguage, FilmRating, Genre, Participation, ParticipationRange, ParticipationValue, and Person. -

News and Notes

Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation Volume 8 Article 11 Issue 4 Rapa Nui Journal 8#4, December 1994 1994 News and Notes Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj Part of the History of the Pacific slI ands Commons, and the Pacific slI ands Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (1994) "News and Notes," Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation: Vol. 8 : Iss. 4 , Article 11. Available at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj/vol8/iss4/11 This Commentary or Dialogue is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation by an authorized editor of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: News and Notes NEWS AND NOTES can be build either above or under ground; a rise in sea level could have major implications; tidal waves are frequent, flooding nearly half of the Marshalls annually; and the What's New in Polynesia nuclear waste would have to be shipped over thousands of Hawai'i. miles ofocean. Ka Lahui, the Hawaiian sovereignty group, has selected Pacific News Bulletin, 9(8):5,7. UNPO (the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization) of Holland to look into a pending state New Zealand. authorized plebiscite on Hawaiian sovereignty, which Ka New Zealand has been accused oflagging behind Australia Lahui claims is illegal. The plebiscite set for October 1995 is, in creating policies for the treatment of indigenous people. -

Henry De Vere Stacpoole

Henry De Vere Stacpoole: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stacpoole, Henry De Vere, 1863-1951 Title: Henry De Vere Stacpoole Collection Dates: 1881-1949, undated Extent: 10 document boxes (4.2 linear feet) Abstract: Henry De Vere Stacpoole, (1863-1951) was an Irish doctor and novelist best known for his novel The Blue Lagoon: A Romance. This collection includes manuscripts, correspondence, and other materials. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-3953 Language: English Access: Open for research. Part or all of this collection is housed off-site and may require up to three business days' notice for access in the Ransom Center's Reading and Viewing Room. Please contact the Center before requesting this material: [email protected]. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases 1964, 1967 (R1620, R3533) Processed by: Jack Boettcher, 2012 Note: This finding aid replicates some information previously available only in a card catalog. Please see the explanatory note at the end of this finding aid for information regarding the arrangement of the manuscripts as well as the abbreviations commonly used in descriptions. Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Stacpoole, Henry De Vere, 1863-1951 Manuscript Collection MS-3953 2 Stacpoole, Henry De Vere, 1863-1951 Manuscript Collection MS-3953 Works: [Unidentified novel], Ams/ inc with A revisions, [169pp. numbered pages 54-223], Container nd. 1.1 [Unidentified work], Ams with A revisions (92pp), nd. Container 1.2 Container [Untitled article on the real nature of time], Ams with A revisions [4pp on 2ll], nd. 1.3 [Unidentified fragments], Ams/fragments with A revisions [4pp], nd. -

On Sensing Island Spaces and the Spatial Practice of Island-Making: Introducing Island Poetics, Part I

Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 2017, pp. 239-252 On sensing island spaces and the spatial practice of island-making: introducing island poetics, Part I Daniel Graziadei Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich, Germany [email protected] Britta Hartmann University of Tasmania, Australia [email protected] Ian Kinane University of Roehampton, UK [email protected] Johannes Riquet University of Tampere, Finland [email protected] and Barney Samson University of Essex, UK [email protected] ABSTRACT: This two-part paper, co-authored by the members of the Island Poetics Research Group, introduces a larger project on the poetic construction of islands in island fictions across media, genres, and geographical regions. Traditional island scholarship tends to discuss islands as tropes for a set of preconceived and fixed meanings (such as isolation, imprisonment, paradise, remoteness, etc.) and thus often bypasses the complex poetic processes through which islands come to be in literary texts. Our intervention in the debate seeks to offer a precise analysis of the practices and operations through which islands are conceived and reconceived. The two parts of this paper examine different modes of island (re)conception in 20th- and 21st-century island fiction. They discuss fictional islands as particularly mobile spatial figures that raise the question of what an island is, refusing to offer easy answers and allowing for a reconsideration of the role of islands in contemporary discourse. Against potentially essentialist accounts of what islands ‘are’ and ‘mean’, our close readings of key moments within island narratives engage with the processes through which island spaces are constructed in different media. -

Football Interrupts Skydome Concerts

serving the Northern Arizona University community. delays new dormitory By Denise Hagerman about four years ago, but it really didn't get Plans to terminate the on-campus housing bad until the last tw o," he said. shortage are already underway, Jack There are currently 194 women and 46 Heskeih, NAU housing director, said. men on the waiting list for housing, accor Hesketh said the university wants to ob ding to the NAU housing office. tain a new dorm as fast as possible, yet Michael Dannells. director of residence before ar.y solid plans are made a source of life, said the housing office overbooks funding has to be determined. available student housing by I to 2 percent "The state does not allocate money for each year. He said this figure is determined housing, so there are two basic ways to fund by the previous “no shows" during the last a new dorm: revenue bonds and federal semester. loans," Hesketh said. The NAU housing policy is being revised Karen to help overcome many of tne current pro “The Legislature has approved S5.5 blems. Dannells said. million in bonding for the building o f a new "Nothing is finalized and therefore would Manager plans dorm, but we would prefer to obtain federal not give many specifics as to what the up money to do this," he said. coming changes will entail," he said. Federal funds are preferred because bon Future housing assignments will be made Skydome future ding tends to be time consuming and expen only one semester in advance instead of two.