Church Bells of England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Offices, 8 Station Road East, Oxted, Surrey RH8 0BT [email protected] Tel: 01883 722000, Dx: 39359 OXTED

Council Offices, 8 Station Road East, Oxted, Surrey RH8 0BT [email protected] Tel: 01883 722000, Dx: 39359 OXTED If calling please ask for Paige Barlow On 01883 732861 Mr Jeremy Stillman 95-97 High Street, E-mail: [email protected] St Mary Cray Orpington Our ref: 2019/1983/NC BR5 3NH Your ref: Date: 31st January 2020 On behalf of Mr. Suresh Patel TOWN AND COUNTY PLANNING (GENERAL PERMITTED DEVELOPMENT) (AMENDMENT) (ENGLAND) ORDER. SCHEDULE 2, PART 3, CLASS M, OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (GENERAL PERMITTED DEVELOPMENT) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2015 (as amended) Application No. : TA/2019/1983/NC Site : 100 Chaldon Road, Caterham CR3 5PH Proposal : Part change of use of ground from Class A1 use (Retail) to Class C3 use (Residential) to form 1 x 1-bedroom self-contained flat (Prior Notification). I am writing further to the above Notification for a change of use from Class A1(Retail) to Class C3 (dwellinghouses) registered on 12th November 2019. Tandridge District Council, as local planning authority, hereby confirms that PRIOR APPROVAL IS REQUIRED AND IS GIVEN for the proposed development at the above address as described and in accordance with the information that the developer has provided to the local planning authority. INFORMATIVES 1. This written notice confirms that the proposed development would comply with the provisions of Schedule 2, Part 3, Class M of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order (England) 2015 (as amended). 2. The development shall be carried out in accordance with the application details provided to the District Planning Authority by the applicant and scanned on 12th November 2019. -

Church Bells. Part 1. Rev. Robert Eaton Batty

CHURCH BELLS BY THE REV. ROBERT EATON BATTY, M.A. The Church Bell — what a variety of associations does it kindle up — how closely is it connected with the most cherished interests of mankind! And not only have we ourselves an interest in it, but it must have been equally interesting to those who were before us, and will pro- bably be so to those who are yet to come. It is the Churchman's constant companion — at its call he first enters the Church, then goes to the Daily Liturgy, to his Con- firmation, and his first Communion. Is he married? — the Church bells have greeted him with a merry peal — has he passed to his rest? — the Church bells have tolled out their final note. From a very early period there must have been some contrivance, whereby the people might know when to assemble themselves together, but some centuries must have passed before bells were invented for a religious purpose. Trumpets preceded bells. The great Day of Atonement amongst the Jews was ushered in with the sound of the trumpet; and Holy Writ has stamped a solemn and lasting character upon this instrument, when it informs us that "The Trumpet shall sound and the dead shall be raised." The Prophet Hosea was com- manded to "blow the cornet in Gibeah and the trumpet in Ramah;" and Joel was ordered to "blow the trumpet in Zion, and sound an alarm." The cornet and trumpet seem to be identical, as in the Septuagint both places are expressed by σαλπισατε σαλπιγγι. -

Carillon News No. 80

No. 80 NovemberCarillon 2008 News www.gcna.org Newsletter of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America Berkeley Opens Golden Arms to Features 2008 GCNA Congress GCNA Congress by Sue Bergren and Jenny King at Berkeley . 1 he University of California at TBerkeley, well known for its New Carillonneur distinguished faculty and academic Members . 4 programs, hosted the GCNA’s 66th Congress from June 10 through WCF Congress in June 13. As in 1988 and 1998, the 2008 Congress was held jointly Groningen . .. 5 with the Berkeley Carillon Festival, an event held every five years to Search for Improving honor the Class of 1928. Hosted by Carillons: Key Fall University Carillonist Jeff Davis, vs. Clapper Stroke . 7 the congress focused on the North American carillon and its music. The Class of 1928 Carillon Belgium, began as a chime of 12 Taylor bells. Summer 2008 . 8 In 1978, the original chime was enlarged to a 48-bell carillon by a Plus gift of 36 Paccard bells from the Class of 1928. In 1982, Evelyn and Jerry Chambers provided an additional gift to enlarge the instrument to a grand carillon of Calendar . 3 61 bells. The University of California at Berkeley, with Sather Tower and The Class of 1928 Installations, Carillon, provided a magnificent setting and instrument for the GCNA congress and Renovations, Berkeley festival. More than 100 participants gathered for artist and advancement recitals, Dedications . 11 general business meetings and scholarly presentations, opportunities to review and pur- chase music, and lots of food, drink, and camaraderie. Many participants were able to walk Overtones from their hotels to the campus, stopping on the way for a favorite cup of coffee. -

General Index

_......'.-r INDEX (a. : anchorite, anchorage; h. : hermit, hermitage)' t-:lg' Annors,enclose anchorites, 9r-4r,4r-3. - Ancren'Riwle,73, 7-1,^85,-?9-8-' I t2o-4t r3o-r' 136-8, Ae;*,;. of Gloucest"i, to3.- | rog' rro' rr4t r42, r77' - h. of Pontefract, 69-7o. I ^ -r4o, - z. Cressevill. I AnderseY,-h',16' (Glos), h', z8' earian IV, Pope, 23. i eriland 64,88' rrz' 165' Aelred of Rievaulx, St. 372., 97, r34; I Armyq Armitdge, 48, Rule of, 8o, 85, 96-7,- :.o3, tog, tzz,l - 184--6,.rgo-l' iii, tz6, .q;g:' a', 8t' ^ lArthu,r,.Bdmund,r44' e"rti"l1 df W6isinghaffi,24, n8-g. I Arundel, /'t - n. bf Farne,r33.- I .- ':.Ye"tbourne' z!-Jt ch' rx' a"fwi", tt. of Far"tli, 5, r29. I Asceticism,2, 4'7r 39t 4o' habergeon' rr8---zr A.tfr.it"fa, Oedituati, h.'3, +, :'67'8. I th, x-'16o, r78; ; Sh;p-h"'d,V"'t-;:"i"t-*^--- r18'r2o-r' 1eni,.,i. [ ]T"]:*'ll:16o, 1?ti;ll'z' Food' ei'i?uy,- ;::-{;;-;h,-' 176,a. Margaret1 . '?n, ^163, of (i.t 6y. AshPrington,89' I (B^ridgnotjh)1,1:: '^'-'Cfii"ft.*,Aldrin$;--(Susse*),Aldrington (Sussex), -s;. rector of,oI, a. atal Ilrrf,nera,fsslurr etnitatatton tD_rru6rrur\rrrt,.-.t 36' " IAttendants,z' companig?thi,p' efa*i"l n. of Malvern,zo. I erratey,Katherine, b. of LedbutY,74-5, tql' Alfred, King, 16, r48, 168. | . gil*i"", Fia"isiead,zr, I Augustine,St', 146-7' Alice, a. of".6r Hereford, TT:-!3-7. -

Mending Bells and Closing Belfries with Faust

Proceedings of the 1st International Faust Conference (IFC-18), Mainz, Germany, July 17–18, 2018 MENDING BELLS AND CLOSING BELFRIES WITH FAUST John Granzow Tiffany Ng School of Music Theatre and Dance School of Music Theatre and Dance University of Michigan, USA University of Michigan, USA [email protected] [email protected] Chris Chafe Romain Michon Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics Stanford University, USA Stanford University, USA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT to just above the bead line. Figure 2 shows the profile we used with the relative thickness variations between the inner and outer Finite Element Analyses (FEA) was used to predict the reso- surface. nant modes of the Tsar Kolokol, a 200 ton fractured bell that sits outside the Kremlin in Moscow. Frequency and displacement data informed a physical model implemented in the Faust programming language (Functional Audio Stream). The authors hosted a con- cert for Tsar bell and Carillon with the generous support of Meyer Sound and a University of Michigan bicentennial grant. In the concert, the simulated Tsar bell was triggered by the keyboard and perceptually fused with the bourdon of the Baird Carillon on the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor. 1. INTRODUCTION In 1735 Empress Anna Ivanovna commissioned the giant Tsar Kolokol bell. The bell was cast in an excavated pit then raised into scaffolding for the cooling and engraving process. When the supporting wooden structure caught fire, the bell was doused with water causing the metal to crack. -

St. Ignatius Collegian, Vol. 4 (1904-1905) Students of St

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons St. Ignatius Collegian University Archives & Special Collections 1905 St. Ignatius Collegian, Vol. 4 (1904-1905) Students of St. Ignatius College Recommended Citation Students of St. Ignatius College, "St. Ignatius Collegian, Vol. 4 (1904-1905)" (1905). St. Ignatius Collegian. Book 2. http://ecommons.luc.edu/st_ignatius_collegian/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives & Special Collections at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Ignatius Collegian by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. m '•c\<e:?^m^^^>; NON ^'^'ir ^ikm %;MiU»>^ >v. ; t. Jgnatius Collegkn Vol. IV Chicago, 111., Nov., 1904 No. 1 Ci)e (tontetnplation of Autumn. BOUNTEOUS nature has given to mortals a soulful love for A what is beautiful. The faculty exists in every human being, whether civilized or savage; but the degree of its develop- ment in any man may be said to determine the culture, in fact, the very civilization of the individual in question. It is born in every- one ; but in some, it is destined like the seed of the Scriptural para- ble, to die for want of nourishment. In others, it reaches, not per- fect maturity—for such an outcome is beyond the dwarfed capa- bility of humanity—but a sufficient degree of development to render its possessors genial and broad-minded men—a bulwark of morality and a credit to society in general. -

The Recollections of Encolpius

The Recollections of Encolpius ANCIENT NARRATIVE Supplementum 2 Editorial Board Maaike Zimmerman, University of Groningen Gareth Schmeling, University of Florida, Gainesville Heinz Hofmann, Universität Tübingen Stephen Harrison, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Costas Panayotakis (review editor), University of Glasgow Advisory Board Jean Alvares, Montclair State University Alain Billault, Université Jean Moulin, Lyon III Ewen Bowie, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Jan Bremmer, University of Groningen Ken Dowden, University of Birmingham Ben Hijmans, Emeritus of Classics, University of Groningen Ronald Hock, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Niklas Holzberg, Universität München Irene de Jong, University of Amsterdam Bernhard Kytzler, University of Natal, Durban John Morgan, University of Wales, Swansea Ruurd Nauta, University of Groningen Rudi van der Paardt, University of Leiden Costas Panayotakis, University of Glasgow Stelios Panayotakis, University of Groningen Judith Perkins, Saint Joseph College, West Hartford Bryan Reardon, Professor Emeritus of Classics, University of California, Irvine James Tatum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Alfons Wouters, University of Leuven Subscriptions Barkhuis Publishing Zuurstukken 37 9761 KP Eelde the Netherlands Tel. +31 50 3080936 Fax +31 50 3080934 [email protected] www.ancientnarrative.com The Recollections of Encolpius The Satyrica of Petronius as Milesian Fiction Gottskálk Jensson BARKHUIS PUBLISHING & GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GRONINGEN 2004 Bókin er tileinkuð -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

A Proposed Campanile for Kansas State College

A PROPOSED CAMPANILE FOR KANSAS STATE COLLEGE by NILES FRANKLIN 1.1ESCH B. S., Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Science, 1932 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE KANSAS STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND APPLIED SCIENCE 1932 LV e.(2 1932 Rif7 ii. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 THE EARLY HISTORY OF BELLS 3 BELL FOUNDING 4 BELL TUNING 7 THE EARLY HISTORY OF CAMPANILES 16 METHODS OF PLAYING THE CARILLON 19 THE PROPOSED CAMPANILE 25 The Site 25 Designing the Campanile 27 The Proposed Campanile as Submitted By the Author 37 A Model of the Proposed Campanile 44 SUMMARY '47 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 54 LITERATURE CITED 54 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this thesis is to review and formulate the history and information concerning bells and campaniles which will aid in the designing of a campanile suitable for Kansas State College. It is hoped that the showing of a design for such a structure with the accompanying model will further stimulate the interest of both students, faculty members, and others in the ultimate completion of such a project. The design for such a tower began about two years ago when the senior Architectural Design Class, of which I was a member, was given a problem of designing a campanile for the campus. The problem was of great interest to me and became more so when I learned that the problem had been given to the class with the thought in mind that some day a campanile would be built. -

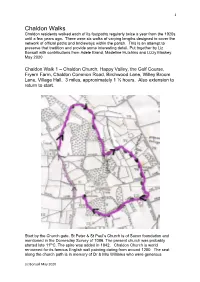

Chaldon Walks Chaldon Residents Walked Each of Its Footpaths Regularly Twice a Year from the 1920S Until a Few Years Ago

1 Chaldon Walks Chaldon residents walked each of its footpaths regularly twice a year from the 1920s until a few years ago. There were six walks of varying lengths designed to cover the network of official paths and bridleways within the parish. This is an attempt to preserve that tradition and provide some interesting detail. Put together by Liz Bonsall with contributions from Adele Brand, Madeline Hutchins and Lizzy Maskey. May 2020 Chaldon Walk 1 – Chaldon Church, Happy Valley, the Golf Course, Fryern Farm, Chaldon Common Road, Birchwood Lane, Willey Broom Lane, Village Hall. 3 miles, approximately 1 ½ hours. Also extension to return to start. Start by the Church gate. St Peter & St Paul’s Church is of Saxon foundation and mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086. The present church was probably started late 11thC. The spire was added in 1842. Chaldon Church is world renowned for its famous English wall painting dating from around 1200. The seat along the church path is in memory of Dr & Mrs Williams who were generous Liz Bonsall May 2020 2 benefactors. Notice the new lamp posts to your left, installed in early 2020 to light the path. There are ancient yew trees in the churchyard and three of the large tombs near the shed have Listed Building status (Grade II). The church itself is a Grade I Listed Building. From the gate you can glimpse 14thC Chaldon Court (Grade II*) through the trees to your left. From the gate walk down the lane keeping the graveyard on your left. On your right is the triangle of Church Green, named as common land on maps from 1825 and 1837. -

The Eastern Mail (Vol. 10, No. 10): September 18, 1856

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby The Eastern Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials 9-18-1856 The Eastern Mail (Vol. 10, No. 10): September 18, 1856 Ephraim Maxham Daniel Ripley Wing Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/eastern_mail Part of the Agriculture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Maxham, Ephraim and Wing, Daniel Ripley, "The Eastern Mail (Vol. 10, No. 10): September 18, 1856" (1856). The Eastern Mail (Waterville, Maine). 477. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/eastern_mail/477 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Waterville Materials at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Eastern Mail (Waterville, Maine) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. T itttgcdlattL). peaceable Insirttmenlalilics gudrflntied by tha Const lution nnd tho laws of the land. In onf judgment, therefore, this, afld Ihi* almost ex. THE MY-STIO BELL. cldsively, Is the question which the hundreds 61 thousands of honest voters shotlld, in (he TBK OP AKDBESIW. present crisis, answer by their ballots, viz Toward err.ning, in the narrow streets of a How can the free principles and the fm msti* iargtt town, just as the sun was sinking, and the iiiiions—the true IJeraocrncy of the Nbrtli— elouds used to glitter Uke gold between the nut the geugrnpliicnl, sectional Nol'lh, btll the cbimflieti, a singular sound, like that of a church North iliflt t-cpt-csents the national AiM^oan bell, was often heard—sometimes by one, ilome- iih-a—be best sustained and extended t Clear times by another; but it only lasted a minute, ly that idea is in perj], Thcreis ho danger of for there was such a rumbling of carts, and’ a dissolution of the Union, biit there is dawger such a din of voicdKt thht slighter noises were I l.at liberty—without which the form hf • fft- drowned. -

Volume I 0.1. 1R-2R Reception of a Papal

Corpus Christi College Cambridge / PARKER-ON-THE-WEB M.R. James, Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge 1912 MS 79 Stanley: C. 3 TJames: 23 Pontifical Pontificale (London) Codicology: Vellum, mm 400 x 255, (15.7 x 10 in.), ff. 24 + cclix, double columns of 30 lines. Cent. xiv-xv, in a fine upright black hand. Music on four-line stave. Collation: 14 (wants 1) 210 (1 canc.) 38 || 44 58-78 (+ slip after 1) 88 98 (5 is half a leaf) 108-138 (+ slip after 3) 148-198 206 218-298 (+ slip after 1) 308-348 (6-8 removed and replaced by) 35 (six) 368 (+ slip after 7) 38 (five). Provenance: Begun for Bishop Mona of St David's[], the book must have been completed after 1407 when Mona[] died and Clifford[] was translated to London[], and, in 1421, on Clifford[]'s death passed to Morgan[], who prefixed the first leaves. A Bishop in Henry VII[]'s time must have added the Office for the reception of a Nuncio. Additions: The decorative work is good throughout: the paintings not of high excellence. Photographic reproductions of a large number of them have been issued by the Alcuin Club under the editorship of the Rev. W. H. Frere[Frere 1901]. Research: Liebermann, p. xxi[Liebermann 1903], calls the MS. Cn and uses it for Excommunication form (p. 434). Decoration: The following is a short list of the subjects represented, besides those specified above. § I. Prima tonsura. Bust of tonsured youth. Ostiarius. Two gold keys.