Overview and Scrutiny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lewisham Learning Demonstration Site Overview

Lewisham learning demonstration site Overview Topic: This project aimed to increase the number of Smoking routine and manual smokers accessing and Organisation: quitting with NHS Stop Smoking Services in Evelyn ward. It estimated to have the highest NHS Lewisham smoking prevalence and highest indices of Location: multiple deprivation in the London borough of Lewisham (London) Lewisham. Dates: The project developed partnerships with September 2007 to April 2010 various local organisations, such as Millwall Budget: Football Club and workplaces, to offer stop £55,000 smoking surgeries at popular venues and at Website: more convenient times. Recruitment drives and www.smokefreelewisham.co.uk partnership promotional events were held in the area and a dedicated Recruitment and Contact: Outreach Workers team was set up to engage Gayle Wallace (Project Manager) with all sectors of the community and foster Email: long-term referral opportunities. [email protected] Results: Telephone: 0208 851 5878 Service data indicated a 21.3 per cent increase in the number of Evelyn residents using NHS Stop Smoking Services from 2008 to 2009. This was greater than the 12 per cent increase across Lewisham as a whole, suggestive of the project's impact The proportion using pharmacy services and sessions run by the outreach workers increased between 2008 and 2009, although the proportion using a GP-based service decreased. These services doubled the number of people quitting during this period ShowCase │ Lewisham 1 learning demonstration site NSMC’s Learning Demonstration Sites Scheme. NHS Lewisham selected Evelyn ward for the social marketing intervention, as part of the delivery of the wider North Lewisham Health The national tobacco strategy for England and Improvement Plan (part of Lewisham’s plan to Wales, contained in the 1998 White Paper reduce health inequalities). -

EVELYN PAPERS (16Th Century-Early 20Th Century) (Add MS 78168-78693) Table of Contents

British Library: Western Manuscripts EVELYN PAPERS (16th century-Early 20th century) (Add MS 78168-78693) Table of Contents EVELYN PAPERS (16th century–Early 20th century) Key Details........................................................................................................................................ 1 Provenance........................................................................................................................................ 2 Add MS 78172–78178 Papers of the Earl of Leicester78172–78178. EVELYN PAPERS. Vols. V–XI. Papers of and relating to Robert......................................................................................................... 8 Add MS 78179–78185 Papers relating to the Royal Household. ([1547–1601])....................................... 16 Add MS 78187–78188 EVELYN PAPERS. Vols. XX, XXI. Horoscopes by John Wells, mathematician and Treasurer of the Stores at............................................................................................................ 25 Add MS 78189–78200 : Official Correspondence ([1631–1682]).......................................................... 27 Add MS 78201–78209 Papers relating to Diplomatic Service ([1575–1665])............................................ 35 Add MS 78210–78219 Privy Council Papers78210–78219. EVELYN PAPERS. Vols. XLIII–LII. Papers of Sir Richard Browne relating to.............................................................................................. 55 Add MS 78220–78224 Family and Personal Correspondence -

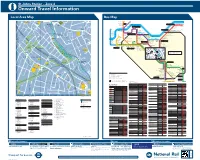

St Johns Station – Zone 2 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

St Johns Station – Zone 2 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 64 DEPTFORD L L I Isis Fibroids BRIDGE 76 H Greenwich 55 1 S P ’ Newington Green 19 E 2 Addey and A R S R & Health 2 DEPTFORD 21 47 O N E River Thames ’ S N E 1 A N 18 BRIDGE Stanhope School B V V 30 A E T D O 60 80 2 Shoreditch Church Celestial R Hoxton Baring Street R G A VANGUARD STREET Church of Christ E Thamesmead East 1 O 44 O N GUILDFORD GROVE H I 1 35 40 CITY Shoreditch High Street Yarnton Way E Greenwich R Old Street A O E THAMESMEAD R 2 River Thames 180 L Deptford H D L Magistrates’ L HARTON STREET T I K 21 Belvedere S H A 2 T Court B 125 L E C 1 Abbey Wood S D I N Moorgate R ’ Liverpool Street Industrial Area 50 M L D E R Bridge E S E E A E C 11 A L T N L L C S ADMIRAL’S GATE McLeod Road N I T 1 ’ R N O A S K E ROTHERHITHE M 1 T E Bank E G L H T A 20 G E S R T a A E Plumstead Corner R L Rotherhithe E v T A E 33 R T e E T 45 14314 FLORENCE TERRACE n s W H Monument Jamaica Road b EGERTON DRIVE O A 1 199 Plumstead 52 18 R o R 436 VANGUARD STREET u Y L O r A O D 13 225 n Paddington F Woolwich Town Centre for Woolwich Arsenal e 86 Canada Water WOOLWICH HESTON STREET A PLUMBRIDGE STREET 10 R B L A London Bridge 59 D Woolwich Church Street i C DABIN Bermondsey E CRESCENT v 116 2 K Footbridge L for Guy’s Hospital e H A E Edgware Road Tooley Street Surrey Quays r Charlton V City SHIP STREET A T T Sussex Gardens Hall Tower Bridge Road Tannersne Hilillll E A L B Y N R O A D Pepys Estate L H East Greenwich Vanbrugh Hill S 7 Wickes 19 S Grove Street EEstate 27 -

Written Representation

Silvertown Tunnel Development Consent Order London Borough of Lewisham Written Representation PINS Reference Document Number LBL 02 Authors LB Lewisham, Project Centre, GVA, Phlorum Revision Date Description 0 November 2016 Deadline 1 Version 1 Silvertown Tunnel Development Consent Order Written Representations by London Borough of Lewisham CONTENTS Summary .............................................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 2. Consultation .................................................................................................................. 7 3. Matters of Support ....................................................................................................... 8 4. Matters of Objection ..................................................................................................... 9 Traffic Congestion ...................................................................................................................... 9 Air Quality and Community Impacts ......................................................................................... 12 Sustainable transport & the Package of River Crossings ......................................................... 19 Consistency with policy ............................................................................................................ 21 Draft Development Consent Order -

Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn As Restoration Virtuosi

SAMUEL PEPYS AND JOHN EVELYN AS RESTORATION VIRTUOSI (with particular reference to the evidence in their diaries) by BERNARD GEORGE WEBBER B.A. University of British Columbia, 1950 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia October, 1962 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada. Date October 4, 1962 V STATEMENT OF THESIS After the civil conflicts of the seventeenth century, England during the Restoration period began to emerge as a modern nation* As Charles II understood, and as James II was to learn at the cost,of his throne, absolute monarchy was no longer acceptable to the kingdom. Although Englishmen might henceforth tolerate the ,- ( trappings of absolutism, the substance was irrevocably gone. This 1 was as true of absolutism in religion as it was in government. It was only a question of time before the demands of Englishmen for freedom in belief and for participation in government would find expression in parliamentary democracy and in religious toleration. -

Written Guide

District 45 A self guided walk in London’s Deptford Find out about Deptford’s Victorian wealth and poverty Visit the streets described by social reformer Charles Booth Discover rich maritime history and today’s vibrant communities Explore how Deptford has and hasn’t changed over a century .discoveringbritain www .org ies of our land the stor scapes throug discovered h walks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed route maps 8 Commentary 10 Further information 37 Credits 38 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2012 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Section of Charles Booth’s 1902 Poverty map © Charles Booth Online Archive, LSE 3 District 45 Travel back in time to London’s Deptford 100 years ago Greenwich, with its spectacular riverfront location and grand buildings, is associated with England’s glory days as a maritime nation. But its neighbour Deptford is steeped in just as much history of the sea. It was where ships docked and unloaded their cargos, where foreigners came to learn the art of shipbuilding, where sailors waved farewell to England as Part of Charles Booth’s poverty map of Deptford (1902) © Charles Booth Online Archive, LSE they headed out across the empire. This walk paints a picture of life in Deptford over a hundred years ago, when it was a working neighbourhood of bustling docks and wharves, busy streets and overcrowded houses, poverty and deprivation alongside affluence and comfort. -

Committee PLANNING COMMITTEE B Report Title 402-404 Evelyn Street, London, SE8 5QL Ward Evelyn Ward Contributors Patrycja Ploch Class PART 1 5Th September 2019

Committee PLANNING COMMITTEE B Report Title 402-404 Evelyn Street, London, SE8 5QL Ward Evelyn ward Contributors Patrycja Ploch Class PART 1 5th September 2019 Reg. Nos. DC/19/111176 Application dated 26th February 2019 Applicant John Farquhardon Partnership on behalf of Lowden Roofing Supplies Ltd Applicant’s Plan Nos PR98.01; PR98.02 Rev.B; PR98.03 Rev.C; PR98.05 Rev.C; PR98.08 Rev.C; PR98.11 Rev.A received on 27 February 2019; 8446- SK01 received on 21st March 2019; PR98.04 REV.E received on 12 April 2019; PR98.07 Rev L and PR98.09 Rev J received on 19th July 2019. Proposal The construction of a three storey building on the site of 402-404 Evelyn Street, SE8, to provide 4 commercial units at ground floor, 2 one bedroom and 6 two bedroom self-contained flats on the upper floors, together with the provision of green roof, bin storage and cycle parking spaces to the rear. Background Papers (1) DE/151/402/TP (2) NPPF (2019) (3) Core Strategy (2011) (4) Development Management Plan (2014) (5) London Plan (2016) Designation Deptford High Street Conservation Area Area of Archaeological Priority Major District Centre Shopping Non-Core Area Deptford Neighbourhood Forum Flood Zone 3 1 SUMMARY 1 This report sets out officer’s recommendation concerning the above proposal. The application has been brought before members for a decision as permission is recommended to be approved and local amenity group objected to it. 1.1 SITE DESCRIPTION AND CURRENT USE 2 The application site is located on the south-west side of Evelyn Street (A200). -

Buses from South Bermondsey

Buses from South Bermondsey 1 N1 Tottenham Court Road Route finder Bus route Towards Bus stops 1 Canada Water ¿†pbNaı Tottenham Court Road N381 Holborn πœgpFy Whitehall 381 County Hall {¿†Òb]Naı Horse Guards Parade Peckham πœ\ÚgFy\ P12 Brockley Rise ÓÔ\Úefg: Aldwych River Thames Westminster for Covent Garden Surrey Quays {ÎÏÒbcd[ Parliament Square Salter Road Salter Road ROTHERHITHE Smith Close Bywater Place River Thames Night buses Rotherhithe Salter Road Waterloo Bridge Peter Hills School Bus route Towards Bus stops Southwark Thamesmead Tooley Street Jamaica Road Brunel Road Salter Road N1 ¿†pbNaı Street Tooley Street Jamaica Road Russia Dock Road County Hall for Tate Modern City Hall Tanner Street Abbey Street Bermondsey Southwark Park Rotherhithe Tunnel Tottenham Court Road πœgpFy 381 N381 Peckham πœ\ÚgFy\ Waterloo London Bridge Tooley Street Jamaica Road Jamaica Road Jamaica Road Salter Road Boss Street Dockhead St. James’s Road Drummond Road Lower Road Downtown Road Trafalgar Square {¿†Òb]Naı for IMAX Cinema, Neptune Street/St. Olaves Estate London Eye Southwark Park Road and Southbank Kirby Estate Lower Road Arts Centre Salter Road Surrey Quays Road Lady Dock Path/The Ship York Redriff Road S Surrey Quays Road Key O Canada Street Brunswick Quay Elephant & Castle CLEMENTS ROAD d U T H e W 1 Day buses in black A Surrey Quays Road Redriff Road R N1 Night buses in blue S K Surrey Quays Leisure Park Onega Way T P 1 . A O R — Connections with London Underground J R Canada Water O Tower Bridge Road A K Surrey A Bus Station M o Connections -

Final Public Questions.Pdf

Question Q Time PUBLIC QUESTION NO 1. Priority 1 LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM COUNCIL MEETING 18 JULY 2018 Question asked by: Nancy Taylor Member to reply: Councillor McGeevor Question Given that Paragraph 5.1 of Land Use Consultants’ ecology report for Beckenham Place Park says:- “5.1 The site is a Local Nature Reserve (LNR) and a Site of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC). The designations describe the site as: ‘One of the best wildlife sites in the Borough with a variety of high quality habitats. These include the most extensive ancient woodland in Lewisham, the most diverse acid grassland, the most natural stretch of river, probably the oldest pond and the only willow carr. Some of the parkland trees are very old and pre-date the landscaping of the park. The high diversity of plants and animals include numerous locally rare species and several nationally rare invertebrates have been recorded’.” Would the council explain why they authorised an Mountain Bike (MTB) trail to pass through part of previously untouched ancient woodland during the December 2017 and January 2018 Beastway events? Reply The woodlands of Beckenham Place Park are extensive and a number of trails already pass through them. When we were approached by an event organiser seeking consent for a series of three morning race sessions the Council’s ecological officers inspected and advised on the proposed routes, which mostly used existing walking routes through the woodland or the open grasslands. The authorised routes avoided the most ecologically sensitive areas of woodland and were timed to take place in the winter outside of nesting season and when flora was dormant. -

Cllr Evelyn Akoto, Cabinet Member for Community Safety and Public Health, Southwark Council – Written Evidence (FPO0024)

Cllr Evelyn Akoto, Cabinet Member for Community Safety and Public Health, Southwark Council – Written evidence (FPO0024) SUMMARY 01. As a London borough, Southwark has seen an increase in the number of residents who are struggling to afford basic food items, especially people who rely on benefits and those who are struggling to make ends meet with insufficient salaries. While it is hard to accept that people in 21st century Britain are going hungry, we are passionate in doing what we can to tackle it. We welcome this inquiry as it look at key aspects driving this and the important interlink between inequality, health inequalities and food sustainability. 02. National figures suggest that one in five over 16 year olds in England are food insecure to some degree, and one in 12 are moderately to severely food insecure. This translates to 53,000 of our residents being somewhat food insecure and over 20,000 being so food insecure that they may be skipping meals because they cannot afford to eat and experience real hunger. Simultaneously, food banks in the borough have seen a 31% and 45% increases respectively in referrals during 2017-18, with no sign of the demand abating in the future. 03. As will be made clear in our response, there are principally five reasons behind this, according to evidence available in the borough and academic research: declining or stagnant wages, welfare reform, destitution, no recourse to public funds, and the interaction between ‘food deserts’ and the ‘poverty premium’. Together, these factors create environments where low-income residents struggle to generate sufficient incomes with little or no access to healthy, fresh food options. -

Task Two: Key Objectives and Priorities 3

15 Task Two: Key objectives and priorities 3 North Lewisham Links 2012 Update | December 2012 16 3 North Lewisham Links 2012 Update | December 2012 3.0 Task Two: Key objectives and priorities 17 Since the Links Strategy was completed in 2007, Priority Route One improvements have been In addition to these assessment criteria, reference has also been made to the principles and vision implemented, a number of development sites have gained planning permission, and the extension of of the Green Grid (South East London Green Chain and Green Grid Area) to inform the identification the East London Line through Bridge House Meadows has been completed. This provides a greater and prioritisation of projects for future phases of the Links Strategy. For example, the Green Grid degree of certainty over the future of the area, however there remains a degree of uncertainty about mapping identifies north Lewisham as an area deficient in a District Park and with a deficiency of the timing of some of the proposed developments, and until they become committed with secured Wildlife Sites and Access to Nature. There are also strategic routes within the area such as the Thames funding, their specific relevance in terms of the delivery or timing of new links and routes will remain Path, Green Chain Walk and Waterlink Way that are important local assets connecting Deptford, New fluid. Given this situation, it is considered important to develop a flexible approach to the prioritisation, Cross and its river frontage to adjoining Boroughs and the wider Thames Gateway. Whilst providing a scoping, timing and funding of new projects. -

Huntsman House

2 EVELYN STREET LONDON SE8 5QU HUNTSMAN HOUSE WAREHOUSE & OFFICES AVAILABLE TO LET 51,583 SQ FT DETACHED SELF-CONTAINED WAREHOUSE FRONTED BY A 2-STOREY BRICK-BUILT 51,583 SQ FT OFFICE UNIT. The unit benefits from 4 separate INDUSTRIAL warehouse bays and a total of 7 surface level loading doors. The minimum eaves height is 6.8 metres, UNIT TO LET rising to 7.9 metres. SUITABLE FOR CITY LOGISTICS OCCUPIERS WITH 7 LEVEL ACCESS LOADING DOORS AND DEDICATED YARD SPECIFICATION ACCOMMODATION Use Sq Ft Sq M 6.8–7.9M EAVES Warehouse 31,419 2,919 7 SURFACE LEVEL LOADING DOORS Mezzanine 9,018 828 Workshop / Store GF 4,420 411 SECURE DEDICATED YARD Workshop / Store FF 4,400 409 Office / Ancillary GF 1,166 108 2-STOREY OFFICES Office / Ancillary FF 1,160 107 Total 51,583 4,792 WORKSHOP / STORAGE SITE PLAN 8,897 SQ FT (826 SQ M) 15,173 SQ FT GF 4,420 SQ FT (411 SQ M) MEZZANINE 3,122 SQ FT (1,410 SQ M) FF 4,400 SQ FT (409 SQ M) 7,349 SQ FT (682 SQ M) (290 SQ M) MEZZANINE 5,896 SQ FT OFFICE / ANCILLARY (548 SQ M) GF 1,166 SQ FT (108 SQ M) FF 1,160 SQ FT (108 SQ M) CLICK FOR A FILM FLYTHROUGH Illustration not to scale, indicative only A A 4 1 0 TERMS 1 DAGENHAM A PROMINENT LOCATION WITH A13 Upon application. CENTRAL A13 EASY ACCESS TO THE MOTORWAY LONDON A 2 GREENWICH NETWORK AND CENTRAL LONDON.