Where Else Is the Money? a Study of Innovation in Online Business Models at Newspapers in Britain’S 66 Cities’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA Publisher/RRO Title Title code Ad Sales Newquay Voice NV Ad Sales St Austell Voice SAV Ad Sales www.newquayvoice.co.uk WEBNV Ad Sales www.staustellvoice.co.uk WEBSAV Advanced Media Solutions WWW.OILPRICE.COM WEBADMSOILP AJ Bell Media Limited www.sharesmagazine.co.uk WEBAJBSHAR Alliance News Alliance News Corporate ALLNANC Alpha Newspapers Antrim Guardian AG Alpha Newspapers Ballycastle Chronicle BCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymoney Chronicle BLCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymena Guardian BLGU Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Chronicle CCH Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Northern Constitution CNC Alpha Newspapers Countydown Outlook CO Alpha Newspapers Limavady Chronicle LIC Alpha Newspapers Limavady Northern Constitution LNC Alpha Newspapers Magherafelt Northern Constitution MNC Alpha Newspapers Newry Democrat ND Alpha Newspapers Strabane Weekly News SWN Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Constitution TYC Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Courier TYCO Alpha Newspapers Ulster Gazette ULG Alpha Newspapers www.antrimguardian.co.uk WEBAG Alpha Newspapers ballycastle.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBCH Alpha Newspapers ballymoney.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBLCH Alpha Newspapers www.ballymenaguardian.co.uk WEBBLGU Alpha Newspapers coleraine.thechronicle.uk.com WEBCCHR Alpha Newspapers coleraine.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBCNC Alpha Newspapers limavady.thechronicle.uk.com WEBLIC Alpha Newspapers limavady.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBLNC Alpha Newspapers www.newrydemocrat.com WEBND Alpha Newspapers www.outlooknews.co.uk WEBON Alpha Newspapers www.strabaneweekly.co.uk -

Future for Local and Regional Media

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future for local and regional media Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 March 2010 HC 43-II (Incorporating HC 699-i-iv of Session 2008-09) Published on 6 April 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon and East Chelmsford) (Chair) Mr Peter Ainsworth MP (Conservative, East Surrey) Janet Anderson MP (Labour, Rossendale and Darwen) Mr Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr Mike Hall MP (Labour, Weaver Vale) Alan Keen MP (Labour, Feltham and Heston) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Adam Price MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) The following members were also members of the committee during the inquiry: Mr Nigel Evans MP (Conservative, Ribble Valley) Helen Southworth MP (Labour, Warrington South) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

Trinity Mirror…………….………………………………………………...………………………………

Annual Statement to the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO)1 For the period 1 January to 31 December 2017 1Pursuant to Regulation 43 and Annex A of the IPSO Regulations (The Regulations: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/1240/regulations.pdf) and Clause 3.3.7 of the Scheme Membership Agreement (SMA: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/1292/ipso-scheme-membership-agreem ent-2016-for-website.pdf) Contents 1. Foreword… ……………………………………………………………………...…………………………... 2 2. Overview… …………………………………………………..…………………...………………………….. 2 3. Responsible Person ……………………………………………………...……………………………... 2 4. Trinity Mirror…………….………………………………………………...……………………………….. 3 4.1 Editorial Standards……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 4.2 Complaints Handling Process …………………………………....……………………………….. 6 4.3 Training Process…………………………………………....……………...…………………………….. 9 4.4 Trinity Mirror’s Record On Compliance……………………...………………………….…….. 10 5. Schedule ………………………………………………………………………...…...………………………. 16 1 1. Foreword The reporting period covers 1 January to 31 December 2017 (“the Relevant Period”). 2. Overview Trinity Mirror PLC is one of the largest multimedia publishers in the UK. It was formed in 1999 by the merger of Trinity PLC and Mirror Group PLC. In November 2015, Trinity Mirror acquired Local World Ltd, thus becoming the largest regional newspaper publisher in the country. Local World was incorporated on 7 January 2013 following the merger between Northcliffe Media and Iliffe News and Media. From 1 January 2016, Local World was brought in to Trinity Mirror’s centralised system of handling complaints. Furthermore, Editorial and Training Policies are now shared. Many of the processes, policies and protocols did not change in the Relevant Period, therefore much of this report is a repeat of those matters set out in the 2014, 2015 and 2016 reports. 2.1 Publications & Editorial Content During the Relevant Period, Trinity Mirr or published 5 National Newspapers, 207 Regional Newspapers (with associated magazines, apps and supplements as applicable) and 75 Websites. -

Mapping Changes in Local News 2015-2017

Mapping changes in local news 2015-2017 More bad news for democracy? Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community (Bournemouth University) https://research.bournemouth.ac.uk/centre/journalism-culture-and-community/ Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power (King’s College London) http://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/policy-institute/CMCP/ Goldsmiths Leverhulme Media Research Centre (Goldsmiths, University of London) http://www.gold.ac.uk/media-research-centre/ Political Studies Association https://www.psa.ac.uk The Media Reform Coalition http://www.mediareform.org.uk For an electronic version of this report with hyperlinked references please go to: http://LocalNewsMapping.UK https://research.bournemouth.ac.uk/centre/journalism-culture-and-community/ For more information, please contact: [email protected] Research: Gordon Neil Ramsay Editorial: Gordon Neil Ramsay, Des Freedman, Daniel Jackson, Einar Thorsen Design & layout: Einar Thorsen, Luke Hastings Front cover design: Minute Works For a printed copy of this report, please contact: Dr Einar Thorsen T: 01202 968838 E: [email protected] Published: March 2017 978-1-910042-12-0 Mapping changes in local news 2015-2017: More bad news for democracy? [eBook-PDF] 978-1-910042-13-7 Mapping changes in local news 2015-2017: More bad news for democracy? [Print / softcover] BIC Classification: GTC/JFD/KNT/KNTJ/KNTD Published by: Printed in Great Britain by: The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community Dorset Digital Print Ltd Bournemouth University 16 Glenmore Business Park Poole, England Blackhill Road Holton Heath BH12 5BB Poole 2 Foreword Local newspapers, websites and associated apps The union’s Local News Matters campaign is are read by 40 million people a week, enjoy a about reclaiming a vital, vigorous press at the high level of trust from their readers and are the heart of the community it serves, owned and lifeblood of local democracy. -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Awards for Excellence in Journalism 2020

Awards for Excellence in Journalism National Council for the Training of Journalists AWARDS FOR EXCELLENCE IN JOURNALISM 2020 HOSTED BY Awards for Excellence in Journalism The NCTJ Awards for Excellence recognise and reward the best journalism students, apprentices and trainees. With quality training at the heart of the NCTJ, these awards highlight the achievements of individuals with promising journalism careers ahead of them. Congratulations to all of our winners, and to everyone who has been commended and highly commended for this year’s awards. INNOVATION OF THE YEAR In times of great change in the media industry, this award aims to encourage and recognise innovation in journalism education and training. Launched in 2017, the Innovation of the Year Award recognises the unique contribution NCTJ centres make to the education and training of journalists on accredited courses. It is open to centres that have improved upon – or extended beyond – current expectations of best practice in education and training. News Associates WINNER News Associates is our winner for the course team's efforts in adapting teaching styles and exercises for remote learning, which was described by the judges as ‘impressive, innovative and pioneering’. The whole team kept morale up for students by encouraging themed fancy dress in lessons, online shorthand study groups in the evening and Zoom yoga session run by a part-time student. Staff, alumni and students offered their top tips for working from home via social media and the online journalism workshops were very successful. University of Brighton HIGHLY COMMENDED Highly commended is the University of Brighton for its virtual exchange with the University of Florida. -

The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education

Journalism Education ISSN: 2050-3903 Journalism Education The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education Volume Nine, No: One Spring 2020 Page 2 Journalism Education Volume 9 number 1 Journalism Education Journalism Education is the journal of the Association for Journalism Education a body representing educators in HE in the UK and Ireland. The aim of the journal is to promote and develop analysis and understanding of journalism education and of journalism, particu- larly when that is related to journalism education. Editors Sallyanne Duncan, University of Strathclyde Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University Deirdre O’Neill Huddersfield University Stuart Allan, Cardiff University Reviews editor: Tor Clark, de Montfort University You can contact the editors at [email protected] Editorial Board Chris Atton, Napier University Olga Guedes Bailey, Nottingham Trent University David Baines, Newcastle University Guy Berger, UNESCO Jane Chapman, University of Lincoln Martin Conboy, Sheffield University Ros Coward, Roehampton University Stephen Cushion, Cardiff University Susie Eisenhuth, University of Technology, Sydney Ivor Gaber, University of Sussex Roy Greenslade, City University Mark Hanna, Sheffield University Michael Higgins, Strathclyde University John Horgan, Ireland Sammye Johnson, Trinity University, San Antonio, USA Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln Mohammed el-Nawawy, Queens University of Charlotte An Duc Nguyen, Bournemouth University Sarah Niblock, CEO UKCP Bill Reynolds, Ryerson University, Canada Ian Richards, -

IPSO Annual Statement for Jpimedia: 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020

IPSO annual statement for JPIMedia: 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020 1 Factual information about the Regulated Entity 1.1 A list of its titles/products. Attached. 1.2 The name of the Regulated Entity's responsible person. Gary Shipton, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of JPIMedia and Regional Director of its titles in the South of England, is the responsible person for the company. 1.3 A brief overview of the nature of the Regulated Entity. The regulated entity JPIMedia is a local and regional multimedia organisation in the UK as well as being a national publisher with The Scotsman (Scotland), The Newsletter (Northern Ireland) and since March 2021 nationalworld.com. We provide news and information services to the communities we serve through our portfolio of publications and websites - 13 paid-for daily newspapers, and more than 200 other print and digital publications. National World plc completed the purchase of all the issued shares of JPIMedia Publishing Limited on 2 January 2021. As a consequence, JPIMedia Publishing Limited and its subsidiaries, which together publish all the titles and websites listed at the end of this document, are now under the ownership of National World plc. We continue to set the highest editorial standards by ensuring that our staff are provided with excellent internally developed training services. The Editors' Code of Practice is embedded in every part of our editorial operations and we commit absolutely to the principles expounded by IPSO. JPIMedia continues to operate an internal Editorial Governance Committee with the key remit to consider, draft, implement and review the policies, procedures and training for the whole Group to ensure compliance with its obligations under IPSO. -

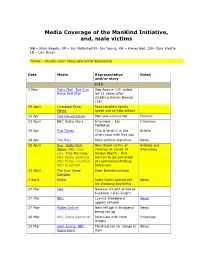

Media Coverage of the Mankind Initiative, And, Male Victims

Media Coverage of the ManKind Initiative, and, male victims MB – Mark Brooks, IM – Ian McNicholl,IY- Ian Young, KB – Kieron Bell, SW- Sara Westle LB – Lori Busch Yellow – denote court cases and initial disclosures Date Media Representative Detail and/or story 2018 3 May Daily Mail, The Sun, Zoe Adams (19) jailed News and Star for 11 years after stabbing Kieran Bewick (18) 29 April Liverpool Echo, Paul Lavelle’s family Metro speak out to help others 26 Apr The Conversation Men are victims too Feature 23 April BBC Radio Worc Interview – Ian Interview McNicholl 19 Apr The Times This is what it is like Article when your wife hits you 18 Apr The Sun Male victims statistics News 16 April Sun, Daily Mail, Alex Skeel victim of Articles and Metro, BBC Five violence at hands of interviews Live, This Morning, Jordan Worth - first BBC Radio Scotland, woman to be convicted BBC Three Counties, of coercive/controlling BBC Breakfast behaviour 13 April The Sun (Dear Dear Deirdre column Deirdre) 7 April Mirror Jodie Owen spared jail News for stabbing boyfriend 29 Mar Mail Nasreen Knight attacked husband Julian knight 27 Mar BBC Lavinia Woodward News appeal refused 27 Mar Wales Online New refuge in Bridgend News being set up 26 Mar BBC Radio Somerset Interview with Mark Interview Brooks 23 Mar Kent online, BBC ManKind call for refuge in News Radio Kent Kent 14-16 Mar Stoke Sentinel, BBC Pete Davegun fundraiser Radio Stoke, Crewe Guardian, Staffs Live 19 Mar Victoria Derbyshire Mark Brooks interview Interview 12 Mar Somerset Live ManKind Initiative appeal -

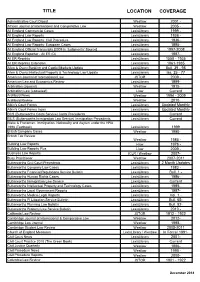

Title Location Coverage

TITLE LOCATION COVERAGE Administrative Court Digest Westlaw 2001 - African Journal of International and Comparative Law Westlaw 2005 - All England Commercial Cases LexisLibrary 1999 - All England Law Reports LexisLibrary 1936 - All England Law Reports: Civil Procedure LexisLibrary 1936- All England Law Reports: European Cases LexisLibrary 1995- All England Official Transcripts [2009 in ‘Judgments’ Source] LexisLibrary 1997-2008 All England Reporter - All ER (D) LexisLibrary 1997- All ER Reprints LexisLibrary 1558 - 1935 All ER Reprints Extension LexisLibrary 1861-1935 Allen & Overy Banking and Captial Markets Update LexisLibrary Bull. 39 - 98 Allen & Overy Intellectual Property & Technology Law Update LexisLibrary Iss. 25 - 77 American Journal of International Law JSTOR 2009 - American Law and Economics Review LexisLibrary 1999- Arbitration (Journal) Westlaw 1915- Arbitration Law (Looseleaf) i-law Current Archbold News Westlaw 1994 - 2009 Archbold Review Westlaw 2010- Atkin's Court Forms LexisLibrary Updated Monthly Atkin's Court Forms Index LexisLibrary Updated Monthly BCS (Butterworths Costs Service) Costs Precedents LexisLibrary Current BILS (Butterworths Immigration Law Service) Immigration Precedents LexisLibrary Current Blake & Fransman: Immigration, Nationality and Asylum under the HRA 1998 (Textbook) LexisLibrary 1999 British Company Cases Westlaw 1990- British Tax Review Westlaw 1986 - Building Law Reports i-law 1976 - Building Law Reports Plus i-law 2009 - Business Law Reports ICLR / Westlaw 2007- Busy Practitioner Westlaw 2007-2011 Butterworths Civil Court Precedents LexisLibrary 2 Month Updates Butterworths Company Law Cases LexisLibrary 1983 - Butterworths Financial Regulations Service Bulletin LexisLibrary Bull. 1 - Butterworths Human Rights Cases LexisLibrary 1996- Butterworths Immigration Law Service LexisLibrary Current Butterworths Intellectual Property and Technology Cases LexisLibrary 1999- Butterworths Local Government Reports LexisLibrary 1997- Butterworths Medico-Legal Reports LexisLibrary Vol. -

Business Wire Catalog

UK/Ireland Media Distribution to key consumer and general media with coverage of newspapers, television, radio, news agencies, news portals and Web sites via PA Media, the national news agency of the UK and Ireland. UK/Ireland Media Asian Leader Barrow Advertiser Black Country Bugle UK/Ireland Media Asian Voice Barry and District News Blackburn Citizen Newspapers Associated Newspapers Basildon Recorder Blackpool and Fylde Citizen A & N Media Associated Newspapers Limited Basildon Yellow Advertiser Blackpool Reporter Aberdeen Citizen Atherstone Herald Basingstoke Extra Blairgowrie Advertiser Aberdeen Evening Express Athlone Voice Basingstoke Gazette Blythe and Forsbrook Times Abergavenny Chronicle Australian Times Basingstoke Observer Bo'ness Journal Abingdon Herald Avon Advertiser - Ringwood, Bath Chronicle Bognor Regis Guardian Accrington Observer Verwood & Fordingbridge Batley & Birstall News Bognor Regis Observer Addlestone and Byfleet Review Avon Advertiser - Salisbury & Battle Observer Bolsover Advertiser Aintree & Maghull Champion Amesbury Beaconsfield Advertiser Bolton Journal Airdrie and Coatbridge Avon Advertiser - Wimborne & Bearsden, Milngavie & Glasgow Bootle Times Advertiser Ferndown West Extra Border Telegraph Alcester Chronicle Ayr Advertiser Bebington and Bromborough Bordon Herald Aldershot News & Mail Ayrshire Post News Bordon Post Alfreton Chad Bala - Y Cyfnod Beccles and Bungay Journal Borehamwood and Elstree Times Alloa and Hillfoots Advertiser Ballycastle Chronicle Bedford Times and Citizen Boston Standard Alsager