UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 2 V1.Indd

ALAIssueALA 2 CognotesNew Orleans Sunday, June 25, 2006 Today's Yellow Swarm Invades New Orleans By Caroline Labbe, Project sites on Friday includ- One of the pleasures of the astated ninth ward, Holy Cross Highlights Student Volunteer,Catholic ed the Algiers, Alvar, Hubbell, day was seeing what a difference High School in Orleans Parish, University of America and Nix branches of the New a few hours and a group of mo- 15 ALA volunteers, along with Bookcart Drill Team Orleans Public Library, the Chil- tivated volunteers could make. a few community volunteers, World Championship! ive hundred eager librar- dren’s Resource Center, Delgado At one project site in the dev- Continued on page 3 1:30-3:30 p.m. ians dressed in bright Community College, Common Morial Convention Fyellow t-shirts poured Ground, Habitat for Humanity, Center Hall F out of the convention center Operation Helping Hands, Jef- Friday morning to board 14 ferson Parish West, Jefferson ALA President’s busses bound for 19 project Parish East, Resurrection, Sec- sites throughout the New Or- ond Harvest, Ben Franklin High Program Reading: The leans area. These “Libraries School, Southern University, St. Essential Skill Build Community” participants Mary’s, Holy Cross High School, 3:30-5:30 p.m. volunteered their time, skills, and Prompt Succor Church. Morial Convention and labor to New Orleans area Tasks varied by site, ranging Center Auditorium libraries and community orga- from construction, painting, and nizations needing help recover- gardening to shelving, weeding, Sneak Peek of a New ing from Katrina. and packing books. Documentary – The Hollywood Scholar Kevin Starr Discusses Librarian: Librarians in Cinema and Society “Reading: The Essential Skill” 9:00 p.m. -

Professor Walker's CV

8/10 RICHARD AVERILL WALKER Curriculum Vita (Complete) Professor Department of Geography University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720-4740 Telephone: (510) 642-3901/03 Fax: (510) 642-3370 1248 Rose Berkeley, California 94702 Born: October 22, 1947 EDUCATION 1965-1969 Stanford University Stanford, California Economics, B.A., cum laude, 1969 1971-1975 The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering National Defense Education Act Fellowship 1971-74 Ph.D. awarded May 1977 Doctoral Dissertation: The Suburban Solution: Urban Geography and Urban Reform in the Capitalist Development of the United States EMPLOYMENT 1975-1982 Assistant Professor 1982-1989 Associate Professor 1989-present Professor Department of Geography University of California, Berkeley 1994–1999 Chair of Geography 2 PUBLICATIONS Books 1989 The Capitalist Imperative: Territory, Technology and Industrial Growth. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. (w/ M. Storper) 1992 The New Social Economy: Reworking the Division of Labor. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell. (w/ A. Sayer) (Portions of The New Social Economy are reprinted in John Bryson, Nick Henry, David Keeble and Ron Martin (eds.), The Economic Geography Reader: Producing and Consuming Global Capitalism. New York: John Wiley. pp. 143- 47, 1999.) 2004 The Conquest of Bread: 150 Years of Agribusiness in California. New York: The New Press. 2007 The Country in the City: The Greening of the San Francisco Bay Area. University of Washington Press. In Preparation Portrait of a Gone City: The Making of the San Francisco Bay Area Articles and chapters 1973 Wetlands preservation and management on Chesapeake Bay: the role of science in natural resources policy. Coastal Zone Management Journal, 1:1, 75-100. -

The Representation of Junãłpero Serra in California History

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 2010 The Representation of Junípero Serra in California History Robert M. Senkewicz Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Senkewicz, R. M. (2010). The Representation of Junípero Serra in California History. In R. M. Beebe & R. M. Senkewicz (Eds.), To Toil in That Vineyard of the Lord: Contemporary Scholarship on Junípero Serra (pp. 17–52). Academy of American Franciscan History. Copyright © 2010 Academy of American Franciscan History. Reprinted with permission. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTRODUCTION The Representation ofJunipero Serra in California History Robert M. Senkewicz Santa Clara University jUNIPERO SERRA WAS THE SUBJECT OF THE FIRST published book written in Alta California. In September 1784, a week or so after he had celebrated Serra's funeral Mass, Francisco Pal6u, Serra's former student and closest friend, returned to his post at Mission San Francisco de Asis. He spent the next months writing Serra's biography which he entitled Historical Account of the Life and Apos tolic Labors of the Venerable Father Fray Junipero Serra. Pal6u took this manuscript with him when he returned to Mexico City in the summer of 1785. He circulated it among a number of his companions at the Colegio de San Fernando. -

Counting California: Government Information Access Made Easy

Counting California: government information access made easy By Patricia Cruse One of Counting California's unique features is Content Development Manager, California Digital Library that it integrates disparate data from all levels of Now that government information is distributed government. It folds data collections from Counting California: different agencies into a single database in a format government information electronically instead of as printed text, private that a variety of end users can use. Counting access made easy citizens, policymakers, and researchers who rely Pg. 1 on quick access to government data are frustrated California uses the Internet and digital library with the new system's high-tech complexity. The technologies so that California residents can easily old, stable print materials have evolved into a access the growing range of social science and economic Bond Act constantly changing array of digital information from government Library Bond Act media, each with it's status report own formats and agencies. It enables Pg. 2 access methods. researchers and the Similarly, public to discover preservation of historical data is at risk. and interact with contemporary and historical Government agencies often mount new census data, almanac-style statistics, county information on their websites, but do not have a business data, and a range of education, crime, system for preserving historical data as each update election, and demographic information from nearly Telecomm meeting supersedes the previous one. a dozen different sources. addresses challenges A concerned group of data specialists and To get a feel for how Counting California works, in 2002 consider the student or researcher who is interested Pg. -

USC Dornsife in the News Archive - 2012

USC Dornsife in the News Archive - 2012 December Friday, December 21, 2012 OC Weekly highlighted “Barrios to Burbs: The Making of the Mexican-American Middle Class” by Jody Agius Vallejo of sociology. Thursday, December 20, 2012 Los Angeles Times quoted Dan Schnur, director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics, about Gov. Jerry Brown’s high marks for effectiveness. Los Angeles Times quoted Dan Schnur, director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics, about how the Los Angeles mayoral candidates need to differentiate themselves. Tuesday, December 18, 2012 Reel Urban News interviewed Ange-Marie Hancock of political science and gender studies about her report on African American philanthropy in Los Angeles. December 15 to 17, 2012 The Chronicle of Higher Education featured Scott Fraser, USC Provost Professor of Biological Sciences and Biomedical Engineering and director of science initiatives. Fraser said that USC’s interdisciplinary nature is what attracted him to move his research to the university from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Fraser added that USC Dornsife College Dean Steve A. Kay, also recently recruited to the university, likes to explore the limits of his field. Fraser is bringing roughly two dozen people with him from Caltech, three or four of whom will take lab leadership positions at USC. The Chronicle of Higher Education ran a second story. KCET-TV’s “Departures” covered an induction ceremony for Los Angeles’ first poet laureate, chosen in part by Dana Gioia, Judge Widney Professor of Poetry and Public Culture at USC. CBC News (Canada) featured “Planet Without Apes,” a new book by Craig Stanford of biological sciences, co-director of the Jane Goodall Research Center at USC, about possible extinction of the great apes and the biological knowledge that would die with them. -

ACRL News Issue (B) of College & Research Libraries

James Estrada, director of community, and active par the Trecker Library at the ticipation in BCALA. University of Connecticut, Hartford, was presented with People Ernie Ingles, director of li the 1994 Special Achieve braries at the University of ment Award by the Con in the Alberta, received the Out necticut Library Association. standing Academic Librarian Award of the Canadian As Karen Nelson Hoyle, di N ew s sociation of College and rector and curator of the University Libraries, pre Kerlan Collection of Child sented at that society’s an ren’s Literature at the Univer Pam Spiegel nual meeting in Vancouver. sity of Minnesota, received The award is based on ser the 1994 Distinguished vice to the profession, the Alumni Award from St. Olaf planning and implementing College, which she graduated from in 1958. of exemplary library programs, research and For the last 25 years Hoyle has built the Kerlan publication, mentorship, and leadership. Collection into one of the largest such reposi tories in the world. In 1992 she received an Jessie L. Matthews, reference and evening li honorary doctorate from the University of St. brarian at Rutgers University Law Library, has Thomas and the Minnesota Library Association’s been named the 1994 recipient of the Spirit of Distinguished Achievement Award. Law Librarianship Award, presented annually to the American Association of Law Libraries M oham m ed Aman, dean of the School of Li member who makes a contribution toward the brary and Information Science at the Univer improvement of a social condition or the in sity of Wisconsin-Mil creased awareness of a social concern. -

Trustee Tool Kit Forlibrary Leadership

Trustee Tool Kit forLibrary Leadership 1998 Edition California Association of Library Trustees and Commissioners California State Library Dr. Kevin Starr, State Librarian of California Sacramento, 1998 1 Trustee Tool Kit for Library Leadership This publication was supported in whole or in part by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, administered in California by the State Librarian. However, the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services or the California State Library, and no official endorsement by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services or the California State Library should be inferred. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................. 7 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................... 9 Overview............................................................................................................ 10 Chapter 1. Statutory Authority ...................................................................... 12 Statutory Differences of Library Boards ..................................................................... 12 Two Types of Boards ..................................................................................................... -

Santa Clara Magazine, Volume 58 Number 2, Summer 2017 Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Santa Clara Magazine SCU Publications Summer 2017 Santa Clara Magazine, Volume 58 Number 2, Summer 2017 Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Business Commons, Education Commons, Engineering Commons, Law Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Santa Clara University, "Santa Clara Magazine, Volume 58 Number 2, Summer 2017" (2017). Santa Clara Magazine. 31. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag/31 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the SCU Publications at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Magazine by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANTA CLARA MAGAZINE CLARA SANTA Santa Clara Magazine Listening is her Ron Hansen on truth $30 million from the No longer stuff of sci-fi: SUMMER 2017 SUMMER Superpower: Anna and fiction, heroes Leavey Foundation to artificial intelligence Deavere Smith. Page 18 and villains. Page 28 fund innovation. Page 38 and public trust. Page 42 THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE KID THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE KID THE AND BAD, THE GOOD, THE 04/05/17 Explosion of color: purple and orange, blue and gold, red and white painting the length and breadth of California’s landscape—hillside and meadow and desert wash. A superbloom a decade in the making. What caused it? A wet winter sparked unprecedented growth, says Justen Whittall, an associate professor of biology who closely studies California’s native plants and trends in evolution of flowers’ colors. -

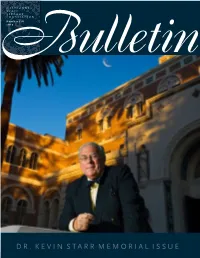

Bulletin Is 44 ��������Recent Contributors Published When We Are Able

CALIFORNIA S T A T E LIBRARY FOUNDATION Number 118 2017 DR. KEVIN STARR MEMORIAL ISSUE CALIFORNIA S T A T E LIBRARY FOUNDATION Number 118 2017 EDITOR 2 . .Kevin Starr Will Never Be Replaced: A Remembrance of the Gary F. Kurutz Historian and Author By Dr. William Deverell EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Kathleen Correia & Marta Knight 6 . .Reminiscences, Recollections, and Remembrances of Dr. Kevin O. Starr, 15th State Librarian of California COPY EDITOR M. Patricia Morris By Cameron Robertson BOARD OF DIRECTORS 12 ����������“A Letter to Dr. Kevin Starr, a.k.a. Dr. Feelgood” By Andrew St. Mary Kenneth B. Noack, Jr. SIDEBAR: A Letter from Dr. Starr to Taylor St. Mary President Donald J. Hagerty 16 ����������A Tribute to Dr. Kevin Starr Delivered at the 2017 Annual Vice-President Meeting of the Society of California Archivists By Mattie Taormina Thomas E. Vinson Treasurer 17 ����������California: An Elegy By Arthur Imperatore III Marilyn Snider 19 ����������Recollections of Kevin Starr By Marianne deVere Hinckle Secretary Greg Lucas 27 ����������When Kevin Starr Ran for the San Francisco State Librarian of California Board of Supervisors: 1984 By Michael S. Bernick JoAnn Levy Marilyn Snider 29 . .Celebrating Dr. Starr’s Genius, Generous Spirit and Phillip L. Isenberg Thomas W. Stallard Astonishing Vision By Dr. C. L. Max Nikias Mead B. Kibbey Phyllis Smith Gary Noy Angelo A. Williams 30 . .Eulogy of Dr. Kevin Starr Highlighting His Ten Years as Jeff Volberg State Librarian of California, 1994—2004 By Gary F. Kurutz Gary F. Kurutz Marta Knight 34 ����������The Sutro Library: Mirror for Global California, March 13, 2013 Executive Director Foundation By Dr. -

Harmony in Diversity Study (PDF)

HARMONY IN DIVERSITY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EFFECTIVE LIBRARY SERVICE TO ASIAN LANGUAGE SPEAKERS Dr. Kevin Starr State Librarian of California California State Library 1998 Edited by Shelly G. Keller eople expand their knowledge and gain new ideas when reading books “P on all kinds of subjects. Reading is the great equalizer because it gives everyone an equal opportunity to learn, acquire skills, and succeed in life. Book reading is a passion that I enjoy very much. I encourage everyone to read, and the world will be at your fingertips.” Benjamin J. Cayetano, Governor of Hawaii This publication was supported in whole or in part by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, administered in California by the State Librarian. However, the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services or the California State Library, and no official endorsement by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services or the California State Library should be inferred. HARMONY IN DIVERSITY HARMONY IN DIVERSITY Recommendations For Effective Library Service To Asian Language Speakers CONTENTS About the Authors 3 Introduction 6 Challenges/Opportunities for Directors and Administrators 8 Practical Advice on Customer Service 10 Personnel and Staff Development 10 Commonalities and Differences of Asian Cultures 13 Communicating with Asian-language Speakers 16 Needs Assessment and Community Analysis 18 Access 21 Materials and Collection Development 23 Marketing and Awareness 25 Technology in Libraries 27 Services 27 Programs 28 Future Implications 29 Bibliography 30 1 HARMONY IN DIVERSITY Acknowledgements Many thanks to the following individuals who con- person; Lisa See, author; W endy Tokuda, anchor, KRON- tributed to and supported this endeavor: Dr . -

Essay Contributors

EssayAContributors Steven M. Avella is an associate professor of history at Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wiscon - sin, specializing in the social and cultural history of twentieth-century America. He received his M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Notre Dame and has written on the intersections of Catholicism with public life in the Midwest and the West. His articles have been published in California History, American Catholic Historical Review, U.S. Catholic Historian, Critic, and Records. He is currently at work on a full-scale biography of C. K. McClatchy. Jeffrey M. Burns is archivist for the Archdiocese of San Francisco and the director of the Academy of American Franciscan History. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Notre Dame and is the author of numerous articles and monographs on American Catholic history. His books include Amer - ican Catholics and the Family Crisis, 1930–1962; Disturbing the Peace: A History of the Christian Family Move - ment, 1949–1974; the multivolume History of the Archdiocese of San Francisco; and a co-edited documentary history, Keeping Faith: European and Asian Catholic Immigrants. Matthew L. Jockers is a consulting assistant professor and academic technology specialist at Stan - ford University. He teaches courses on Irish-American literature and computer methods of literary analysis research. Specializing in Irish and Irish-American literature, he has written extensively about Irish writers in the American West and developed an online database of Irish-American literature. Professor Jockers received his Ph.D. from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. Currently he is Webmaster for the American Conference for Irish Studies and editor of the conference newsletter. -

California State of Mind: the Legacy of Pat Brown Press Kit Contents

California State of Mind: The Legacy of Pat Brown Press Kit Contents Page Synopses (short, medium & long) 2 Crew Bios 4 Press & Quotes about the Film 6 Quotes from the Film 8 Director’s Statement 10 Funding 11 Public Television Distribution 12 Contact 13 For press photos and more information visit kqed.org/pressroom 1 California State of Mind: The Legacy of Pat Brown Synopsis Short During the most turbulent decade of our time, Governor Pat Brown brought California together to create a Superstate. Told from his granddaughter’s perspective, a dynamic American dream story unfolds in this unique portrait of 'the Godfather of Modern California.' Medium In the turbulent 1960’s, an ordinary man rose to face extraordinary challenges. Pat Brown’s granddaughter and award-winning Director, Sascha Rice, gives an inside look into political power and a family dynasty called by some “the West Coast Kennedys.” This premiere account of former Governor Pat Brown’s life takes on startling new significance now that his son, Jerry Brown is Governor of California – again. An exciting tale of the West comes into focus as the filmmaker wrestles with the inherited optimism of her grandfather's legacy. The documentary gracefully pivots from a tumultuous decade in American history to the contemporary challenges that California faces today. This dynamic American Dream story follows the journey of a man overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles to shape the future of modern California. Long In the turbulent 1960’s, an ordinary man rose to face extraordinary challenges. In California State of Mind: The Legacy of Pat Brown the premiere account of former Governor Pat Brown’s life, his granddaughter and award-winning Director, Sascha Rice, gives an inside look into political power and into a family dynasty called by some “the West Coast Kennedys.” California has long been a symbol of the American Dream and in this dynamic new documentary an exciting tale of the West comes into focus as the filmmaker wrestles with the inherited optimism of her grandfather's legacy.