Fo U N D a T I O N B O a Rd M E E T S I N C L a R K S B U Rg M E a D B . K I B B Ey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 2 V1.Indd

ALAIssueALA 2 CognotesNew Orleans Sunday, June 25, 2006 Today's Yellow Swarm Invades New Orleans By Caroline Labbe, Project sites on Friday includ- One of the pleasures of the astated ninth ward, Holy Cross Highlights Student Volunteer,Catholic ed the Algiers, Alvar, Hubbell, day was seeing what a difference High School in Orleans Parish, University of America and Nix branches of the New a few hours and a group of mo- 15 ALA volunteers, along with Bookcart Drill Team Orleans Public Library, the Chil- tivated volunteers could make. a few community volunteers, World Championship! ive hundred eager librar- dren’s Resource Center, Delgado At one project site in the dev- Continued on page 3 1:30-3:30 p.m. ians dressed in bright Community College, Common Morial Convention Fyellow t-shirts poured Ground, Habitat for Humanity, Center Hall F out of the convention center Operation Helping Hands, Jef- Friday morning to board 14 ferson Parish West, Jefferson ALA President’s busses bound for 19 project Parish East, Resurrection, Sec- sites throughout the New Or- ond Harvest, Ben Franklin High Program Reading: The leans area. These “Libraries School, Southern University, St. Essential Skill Build Community” participants Mary’s, Holy Cross High School, 3:30-5:30 p.m. volunteered their time, skills, and Prompt Succor Church. Morial Convention and labor to New Orleans area Tasks varied by site, ranging Center Auditorium libraries and community orga- from construction, painting, and nizations needing help recover- gardening to shelving, weeding, Sneak Peek of a New ing from Katrina. and packing books. Documentary – The Hollywood Scholar Kevin Starr Discusses Librarian: Librarians in Cinema and Society “Reading: The Essential Skill” 9:00 p.m. -

A Framework for Evaluating Urban Land Use Mix from Crowd-Sourcing Data Luciano Gervasoni, Martí Bosch, Serge Fenet, Peter Sturm

A framework for evaluating urban land use mix from crowd-sourcing data Luciano Gervasoni, Martí Bosch, Serge Fenet, Peter Sturm To cite this version: Luciano Gervasoni, Martí Bosch, Serge Fenet, Peter Sturm. A framework for evaluating urban land use mix from crowd-sourcing data. 2nd International Workshop on Big Data for Sustainable Devel- opment, Dec 2016, Washington DC, United States. pp.2147-2156, 10.1109/BigData.2016.7840844. hal-01396792 HAL Id: hal-01396792 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01396792 Submitted on 15 Nov 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A framework for evaluating urban land use mix from crowd-sourcing data Luciano Gervasoni∗, Marti Boschy, Serge Fenetz and Peter Sturmx ∗zxInria Grenoble – Rhone-Alpes,ˆ France ∗xUniv Grenoble Alpes, Lab. Jean Kuntzmann, Grenoble, France ∗xCNRS, Lab. Jean Kuntzmann, F-38000 Grenoble, France yEcole Polytechnique Fed´ erale´ de Lausanne zUniv. Lyon 1/INSA de Lyon, LIRIS, F-69622, Lyon, France Email: ∗[email protected], ymarti.bosch@epfl.ch, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Population in urban areas has been increasing at an extraction is performed from the input data. -

Professor Walker's CV

8/10 RICHARD AVERILL WALKER Curriculum Vita (Complete) Professor Department of Geography University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720-4740 Telephone: (510) 642-3901/03 Fax: (510) 642-3370 1248 Rose Berkeley, California 94702 Born: October 22, 1947 EDUCATION 1965-1969 Stanford University Stanford, California Economics, B.A., cum laude, 1969 1971-1975 The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering National Defense Education Act Fellowship 1971-74 Ph.D. awarded May 1977 Doctoral Dissertation: The Suburban Solution: Urban Geography and Urban Reform in the Capitalist Development of the United States EMPLOYMENT 1975-1982 Assistant Professor 1982-1989 Associate Professor 1989-present Professor Department of Geography University of California, Berkeley 1994–1999 Chair of Geography 2 PUBLICATIONS Books 1989 The Capitalist Imperative: Territory, Technology and Industrial Growth. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. (w/ M. Storper) 1992 The New Social Economy: Reworking the Division of Labor. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell. (w/ A. Sayer) (Portions of The New Social Economy are reprinted in John Bryson, Nick Henry, David Keeble and Ron Martin (eds.), The Economic Geography Reader: Producing and Consuming Global Capitalism. New York: John Wiley. pp. 143- 47, 1999.) 2004 The Conquest of Bread: 150 Years of Agribusiness in California. New York: The New Press. 2007 The Country in the City: The Greening of the San Francisco Bay Area. University of Washington Press. In Preparation Portrait of a Gone City: The Making of the San Francisco Bay Area Articles and chapters 1973 Wetlands preservation and management on Chesapeake Bay: the role of science in natural resources policy. Coastal Zone Management Journal, 1:1, 75-100. -

Summer Guide 2020 Welcome to the Saas Valley – It’S Your Turn to En- Joy Some High-Alpine Time out in the Valais Alps

English Summer Guide 2020 Welcome to the Saas Valley – It’s your turn to en- joy some high-alpine time out in the Valais Alps. Surrounded by eighteen four-thou- sand-metre peaks, a unique mountain and glacier landscape promising endless adven- ture awaits. Whether you want to test your li- mits or are simply looking for relaxation and fun – with us, you have come to the right place. We hope you have lots of fun! INHALT -> 01 Experience the mountains 06 -> 02 Discover the Saas Valley 28 -> 03 Events 44 -> 04 For Families 48 -> 05 Restaurants & Nightlife 54 -> 06 Information 64 Experience the mountains With us, you have to set your sights high. And it’s not without good reason that we are THE high alpine ho- liday resort for all those who seek and love personal challenges. High alpine means: We start where others stop. Experience the difference in altitude on our hi- king trails, bike trails and ski runs. Enjoy the mountain panorama with eighteen four-thousanders and disco- ver our glacier worlds. 01 6 / 7 Experience the mountains CABLEWAYS TIMETABLE -> Saas-Fee June 2020 July 2020 August 2020 September 2020 October 2020 06.06. – 26.06.20 27.06. – 10.07.20 11.07. – 25.10.20 Spielboden 1. Sektion 08:15 – 16:15 07:15 – 16:15 09:00 – 16:15 06.06. – 26.06.20 27.06. – 10.07.20 Closed Felskinnbahn 08:30 – 16:00 07:30 – 16:00 11.07. – 30.08.20 31.08. – 13.09.20 14.09. – 04.10.20 05.10. -

Schoolhouse Lofts Circa 1906

SCHOOLHOUSE LOFTS CIRCA 1906 RESPONSE FOR REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS For The Purchase And Adaptive Reuse of The Calvin Coolidge School October 3, 2019 Table of Contents Cover Letter Our Team Development Plan Proposed Site Plan Historic Preservation Plan Public Components Sustainability Estimated Timeline Financial Considerations Team Experience Resumes | References Floor Plans Appendix References Price Proposal Form Commitment Letter Forms 1-4 Certificate of Non-Collusion Certificate of Tax Compliance Certificate of Authority Real Property Disclosure Proposal Security Deposit Our Team Our team consists of two experienced development firms with complimentary skills and expertise. We are confident that our collaboration on aspects from funding to execution, combined with thoughtful design and an emphasis on placemaking, will result in an unparalleled reuse of the 12 Bancroft Street site. Civico Development Civico is a community-focused real estate investment and development group founded around a commitment to quality design, historic preservation and neighborhood-oriented infill development. Civico strives to instill an intriguing blend of innovative design and civic spirit into all of its projects. Our mission is to design and construct high quality buildings, streetscapes, and neighborhoods that significantly enhance the social livability and environmental sustainability of our communities. Our work incorporates projects of all scales, focused on walkability and human-scale development. Sustainable Comfort Sustainable Comfort, Inc. (SCI) is a Worcester-based construction, property management, and consulting firm with a focus on the green buildings and energy efficient multifamily housing industry. SCI is active throughout the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States, and has nearly thirty (30) years of collective experience in development, design, construction, engineering, administration and management across the multifamily, commercial, and industrial property industries. -

The Representation of Junãłpero Serra in California History

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 2010 The Representation of Junípero Serra in California History Robert M. Senkewicz Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Senkewicz, R. M. (2010). The Representation of Junípero Serra in California History. In R. M. Beebe & R. M. Senkewicz (Eds.), To Toil in That Vineyard of the Lord: Contemporary Scholarship on Junípero Serra (pp. 17–52). Academy of American Franciscan History. Copyright © 2010 Academy of American Franciscan History. Reprinted with permission. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTRODUCTION The Representation ofJunipero Serra in California History Robert M. Senkewicz Santa Clara University jUNIPERO SERRA WAS THE SUBJECT OF THE FIRST published book written in Alta California. In September 1784, a week or so after he had celebrated Serra's funeral Mass, Francisco Pal6u, Serra's former student and closest friend, returned to his post at Mission San Francisco de Asis. He spent the next months writing Serra's biography which he entitled Historical Account of the Life and Apos tolic Labors of the Venerable Father Fray Junipero Serra. Pal6u took this manuscript with him when he returned to Mexico City in the summer of 1785. He circulated it among a number of his companions at the Colegio de San Fernando. -

Zoning Ordinance

ZONING ORDINANCE CITY OF COCHRAN, GEORGIA PREAMBLE An Ordinance of the City of Cochran, Georgia regulating and restricting the use of land, buildings, and structures within the incorporated City of Cochran, Georgia; regulating and restricting the location, construction, height, number of stories and size of buildings and structures, the percentage of lots which may be occupied, the size of yards, and the density and distribution of population; imposing regulations, prohibitions, and restrictions governing the erection, construction, and reconstruction of structures and buildings and the use of lands for business, industry, residence, social, and other various purposes; creating districts for such purposes and establishing the boundaries thereof; providing for the gradual elimination of nonconforming uses of land, buildings, and structures; defining certain terms used herein; providing for the method of administration, enforcement and amendment of such regulations; prescribing penalties for violation of its provisions; repealing conflicting ordinances; and other purposes. ARTICLE 1 – BASIC PROVISIONS 1.1 Title and Authority A. This document shall be formally known as the City of Cochran Zoning Ordinance and it may also be cited and referred to as the Zoning Ordinance, Ordinance, or Code. B. This Ordinance shall be for the purpose of promoting the public health, safety, and general welfare of the city and all of its citizens. C. This Ordinance shall be under the authority of Official Code of Georgia Annotated, Title 36, Chapter 66, Zoning Procedures, and Title 36, Chapter 67, Zoning Proposal Review Procedures, and all acts amendatory thereto. 1.2 Jurisdiction This Ordinance shall apply to all land within the jurisdiction of the City of Cochran, being all portions of the City not in the ownership of the municipal, state, or federal government and to any area for which the City of Cochran Mayor and City Council has jurisdiction consistent with the provisions of Georgia law. -

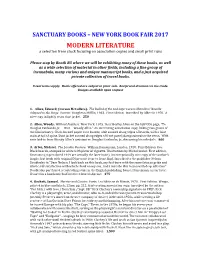

MODERN LITERATURE a Selection from Stock Focusing on Association Copies and Small Print Runs

SANCTUARY BOOKS – NEW YORK BOOK FAIR 2017 MODERN LITERATURE a selection from stock focusing on association copies and small print runs Please stop by Booth B3 where we will be exhibiting many of these books, as well as a wide selection of material in other fields, including a fine group of incunabula, many curious and unique manuscript books, and a just acquired private collection of travel books. Usual terms apply. Books offered are subject to prior sale. Reciprocal discounts to the trade. Images available upon request 1. Albee, Edward; (Carson McCullers). The Ballad of the Sad Cafe: Carson McCullers' Novella Adapted to the Stage. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963. First Edition. Inscribed by Albee in 1978. A nice copy in lightly worn dust jacket. 250 2. Allen, Woody. Without Feathers. New York: 1975. Inscribed by Allen on the half-title page, "To Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. -- Best -- Woody Allen." An interesting association copy, linking two giants of the film industry. Cloth-backed paper over boards; a bit sunned along edges of boards, with a faint stain at tail of spine. Dust jacket sunned along edges of front panel; dampstained on the verso. With note laid-in from Woody Allen’s assistant to Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., discussing his schedule. 800 3. Arlen, Michael. The London Venture. William Heinemann, London, 1920. First Edition. 8vo. Black boards, stamped in white with pictorial vignette. Illustrations by Michel Sevier. First edition, first issue (copies dated 1919 are actually the later issue). An exceptionally nice copy of the author’s fragile first book with original DJ present (tear to front flap). -

Counting California: Government Information Access Made Easy

Counting California: government information access made easy By Patricia Cruse One of Counting California's unique features is Content Development Manager, California Digital Library that it integrates disparate data from all levels of Now that government information is distributed government. It folds data collections from Counting California: different agencies into a single database in a format government information electronically instead of as printed text, private that a variety of end users can use. Counting access made easy citizens, policymakers, and researchers who rely Pg. 1 on quick access to government data are frustrated California uses the Internet and digital library with the new system's high-tech complexity. The technologies so that California residents can easily old, stable print materials have evolved into a access the growing range of social science and economic Bond Act constantly changing array of digital information from government Library Bond Act media, each with it's status report own formats and agencies. It enables Pg. 2 access methods. researchers and the Similarly, public to discover preservation of historical data is at risk. and interact with contemporary and historical Government agencies often mount new census data, almanac-style statistics, county information on their websites, but do not have a business data, and a range of education, crime, system for preserving historical data as each update election, and demographic information from nearly Telecomm meeting supersedes the previous one. a dozen different sources. addresses challenges A concerned group of data specialists and To get a feel for how Counting California works, in 2002 consider the student or researcher who is interested Pg. -

New Dispatch Equipment Cost to Top $100,000

VOLUME 138 • NUMBER 39 October 30, 2019 $1.00 CARROLL COUNTY E911 New dispatch equipment Bryan Moffitt cost to top $100,000 Bryan Moffitt shirleyNANNEY Andy Dickson informed mem- very old and no longer can parts office to the new EOC next to would be paid for drew much Editor bers that a radio console at the be found for it.” the jail. discussion. It is expected to to perform Emergency Operation Center He said there is only one Mike Badgett Jr. with B & E cost between $100,000 and At the Oct. 22 meeting, Car- (EOC) office had crashed and console working now, but that Electronics, who was present at $150,000. at Habitat roll County E911 board mem- was out of service. it was not surprising one went the meeting, advised that he had Although B & E submitted bers learned of some bad news “No longer can a dispatcher down because the equipment been unsuccessful in obtaining two different bids it will have to Gala Nov. 5 that will be costly. sit in a chair and dispatch,” said was not expected to survive the parts for the console. Board Chairman Sheriff Dickson. “The radio system was move from the 126 West Paris How the new equipment See EQUIPMENT, Page 3A Carroll County Habitat for Humanity’s Gala is set for Tuesday, Nov. 5 at 6 p.m. for Hors d’ oeuvres with dinner to start at 6:30 p.m. at the Local mother Carroll County Civic Center. Live entertainment will be by Bryan Moffitt. still fighting Tickets are $50 each and are tax deductible. -

Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction in Children's

Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction in Children’s Literature Charge: To select the recipient of the annual Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children and up to five honor books; to propose a session on nonfiction books for children and plan a session featuring the award winning author at NCTE's Annual Convention; and to promote the use of nonfiction children's books in the classroom. As committee chair, I am grateful for the support provided by the NCTE staff members, Debbie Zagorski and Linda Walters, who continue to supply encouragement, information, and patience. What major actions or projects have been completed by your group pursuant to your charge since July 1, 2012? Since July 2012 the committee announced the winner, honor, and recommended books, from those nonfiction books published in 2011, in an article of reviews for Language Arts and at the national conference in Las Vegas in November 2012. The committee acknowledged a number of authors and illustrators at the children’s literature luncheon. Melissa Sweet, Candace Fleming, Monica Brown, and Julie Paschkis, were honored. Later the authors participated in a round table author discussion about writing and illustrating books for young readers. The committee’s selection of the 2012 Orbis Pictus Award Books was intensive and challenging because of the number of excellent and varied books published for young readers. Features and content were diverse and sometimes controversial; new forms such as the memoir and first-person biography, as well as superb photographs and design continue to renew, expand and invigorate the genre. The concerns about sources and documentation in books for the youngest readers continue to be part of committee discussions. -

File This Lawsuit

JUDGE CAPRONI Dale M. Cendali Joshua L. Simmons Jordan M. Romanoff KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP 601 Lexington A venue New York, New Yark 10022 Telephone: (212) 446-4800 Facsimile: (212) 446-4900 [email protected] [email protected] 19CV [email protected] 7 913 Attorneys for Plaintiffs UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK CHRONICLE BOOKS, LLC; HACHETTE BOOK Case No. ____ GROUP, INC.; HARPERCOLLINS PUBLISHERS LLC; MACMILLAN PUBLISHING GROUP, LLC; ECF Case PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC; SCHOLASTIC INC.; AND SIMON & SCHUSTER, INC. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, - against - AUDIBLE, INC. Defendant. Plaintiffs Chronicle Books, LLC ("Chronicle"), Hachette Book Group, Inc. ("Hachette"), HarperCollins Publishers LLC ("HarperCollins"), Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC. ("Macmillan"), Penguin Random House LLC ("PRH"), Scholastic Inc. ("Scholastic"), and Simon & Schuster, Inc. ("S&S") (collectively, "Publishers" or "Plaintiffs")~ by and through their attorneys, Kirkland & Ellis LLP, for their Complaint, hereby allege against Defendant Audible, Inc. ("Audible") as follows. NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Audible, Inc. unilaterally—without permission from or any notice to Publishers— has decided to introduce a new, unauthorized, feature for its mobile application called, “Audible Captions.” Audible Captions takes Publishers’ proprietary audiobooks, converts the narration into unauthorized text, and distributes the entire text of these “new” digital books to Audible’s customers. Audible’s actions—taking copyrighted works and repurposing them for its own benefit without permission—are the kind of quintessential infringement that the Copyright Act directly forbids. 2. All of the Publishers are member companies of the Association of American Publishers, the mission of which is to be the voice of American publishing on matters of law and public policy.