The History and Ethics of Living Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

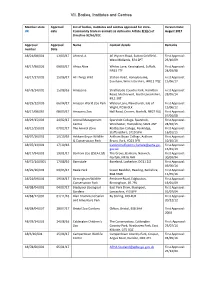

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

WORZ Elephant Report Summary 5 March 2018

WORZ Asian Elephant Facilities and Management Study Summary Prepared for Elephant Planning Workshop, 5 March 2018 Werribee Open Range Zoo − Zoos Victoria Jon Coe Design, Pty. Ltd. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Werribee Open Range Zoo has a unique, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create the world’s best zoo elephant display and management system. It has the expansive site, agreeable climate, motivated and capable staff and most of all the animal welfare mandate to achieve this goal while creating a world-class visitor experience and adding essential research findings benefiting elephant managers the world over. Global populations of wild and traditionally managed elephants are plummeting and the need for self-sustaining insurance populations has never been greater. Thus, this program supports both Zoos Victoria's animal welfare and wildlife conservation mandates. Many in both the global modern zoo community and animal welfare groups agree that despite notable recent progress, zoo elephant facilities and management systems are still not good enough. This realization, supported by recent research and massive public support in many cities, has led to a new Golden Age in zoo elephant design and management, with breakthrough facilities recently across in the US and in Europe. This study profiles research findings from nine ground-breaking international zoo elephant facilities ranging from smaller, urban and intensively managed facilities such as those in Copenhagen and Dublin to expansive and more passively managed exhibits at Boras Djurpark in Sweden and the very green open range facility at North Carolina Zoo. It includes facilities displaying elephants with other species (Dallas Zoo, Boras Djurpark) and exhibits where elephants, rhinos and other species rotate (time share) in ever- moving circuits (Denver Zoo). -

Special Schools Are Going…On a Virtual Tour Zoos and Farms

Special Schools are going…on a Virtual Tour The following are some of the virtual tours that some special school teachers have used. Many students, particularly those with ASD, often enjoy engaging with virtual tours, which can be used to support a variety of curricular areas. Zoos and Farms Dublin Zoo https://www.dublinzoo.ie/animals/animal-webcams/ San Diego Zoo https://kids.sandiegozoo.org/index.php/animals Live Camera from Georgia Aquarium https://www.georgiaaquarium.org/webcam/beluga-whale-webcam/ St Louis Aquarium https://www.stlouisaquarium.com/galleries Visit a Dairy Farm https://www.discoverundeniablydairy.com/virtual-field-trip Canadian Apple Orchard https://www.farmfood360.ca/en/apple-orchard/360-video/ Canadian Egg farm https://www.farmfood360.ca/en/eggfarms/enriched360/ Monterey Bay Aquarium https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/live-cams Smithsonian National Zoo – Webcams https://nationalzoo.si.edu/webcams Museums The Reading Room at the National Library of Ireland https://artsandculture.google.com/streetview/national-library-of-ireland/AQEHJhumim_0mw?sv_lng=- 6.254543300371552&sv_lat=53.34114708608875&sv_h=-27.447228007498325&sv_p=- 15.17881546040661&sv_pid=jHXetPbK6DQgGWgdLx10-A&sv_z=1 National Gallery of Ireland https://www.nationalgallery.ie/virtual-tour Natural History Museum, Dublin https://www.museum.ie/Natural-History/Exhibitions/Current-Exhibitions/3D-Virtual-Visit-Natural-History National Museum of Ireland (Archaeology) https://www.virtualvisittours.com/national-museum-of-ireland-archaeology/ Chester Beatty -

Dublin Zoo Annual Report 2016 Vs.3.Indd 1 21/07/2017 16:17 PAST PRESIDENTS of the ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY of IRELAND

Annual Report 2016 Zoological Society of Ireland Dublin Zoo Annual Report 2016_vs.3.indd 1 21/07/2017 16:17 PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF IRELAND Presidents of the Zoological Society of Ireland*, 1833 to 1837, and 1994 to date; and the Royal Zoological Society of Ireland, 1838-1993. Sir Philip Crampton* 1833 Sir Frederick Moore 1917-21 The Duke of Leinster* 1834 Sir Robert H. Woods 1922-26 Captain Portlock* 1835-36 Prof. A. Francis Dixon 1927-31 Sir Philip Crampton 1837-38 Sir William Taylor 1932-33 The Archbishop of Dublin 1839-40 Lord Holmpatrick 1934-42 Sir Philip Crampton 1841-42 Dr. R. Lloyd Praeger 1942-43 The Archbishop of Dublin 1843-44 Capt. Alan Gordon 1944-50 Sir Philip Crampton 1845-46 Prof. John McGrath 1951-53 The Duke of Leinster 1847-48 Dinnen B. Gilmore 1954-58 Sir Philip Crampton 1849-50 G.F. Mitchell 1959-61 The Marquis of Kildare 1851-52 N.H. Lambert 1962-64 Sir Philip Crampton 1853-54 G. Shackleton 1965-67 Lord Talbot of Malahide 1855-56 Prof. P.N. Meenan 1968-70 Sir Philip Crampton 1857-58 Prof. J. Carroll 1971-73 Doctor D.J. Corrigan 1859-63 A.E.J. Went 1974-76 Viscount Powerscourt 1864-69 Victor Craigie 1977-80 The Earl of Mayo 1870-71 Alex G. Mason 1981-83 Earl Spencer 1872-74 Aidan Brady 1984-86 J.W. Murland 1875-78 John D. Cooke 1987-89 Sir John Lentaigne C.P. 1879-84 Padraig O Nuallain 1990-91 Rev. Dr. Haughton F.R.S. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Zoo Keepers Tend to Be Dedicated and Seal of Approval Passionate People When It Comes to the Animals in Their Care

ZooMatters Summer 2008 copy 18/07/2008 12:02 Page 1 ZooMatters Summer 2008 copy 18/07/2008 12:02 Page 4 really strong and she is suckling well, which is fantastic.” This significant birth at Dublin Zoo is a result of the successful selection of the herd and many years of patience, plotting and planning. Zoo Keepers tend to be dedicated and Seal of Approval passionate people when it comes to the animals in their care. You might think Born on June 9 to mother Ciara an as yet unnamed female sealion pup, weighed in at a healthy 7kgs. Both mother therefore, that a full time job caring for and pup are thriving. animals would be enough. Not true. Many of them spend their spare time visiting Cameroon New Rhino Calf with mother Ashanti other zoos, gaining knowledge from seeing Dublin Zoo is delighted to officially welcome their chosen species in the wild or offering its newest additions. A Californian sealion pup needed help in sanctuaries around the and a white rhino calf. Read on for more... world. Here Dublin Zoo Keeper Yvonne McCann describes her time in West Africa One of the most recent arrivals to charge into Dublin Zoo working in a sanctuary for chimpanzees. is a female Southern White Rhino calf. The birth occurred at approximately 10pm on Wednesday 28th May I was greeted first by ‘Che Guevara’, a feisty three year to mother Ashanti. old, not the biggest but definitely the boss of the group. ‘Nunaphar’,‘Patchouli’,‘Etoile’,‘Kiwi’,‘Arthenis’ and Keepers at Dublin Zoo discovered that Ashanti was eventually little ‘Masai’ all came to investigate. -

1 Complaints Policy the Zoological Society of Ireland Adopted by The

COMPLAINTS POLICY THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF IRELAND ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON 19 NOVEMBER 2020 1 The Zoological Society of Ireland Complaints Policy in respect of fundraising activities The Zoological Society of Ireland (the “Charity”) is committed to ensuring that all of our communications and dealings with the general public and our supporters are of the highest possible standard. We listen and respond to the views of the general public and our supporters. The Charity welcomes both positive and negative feedback. Therefore we aim to ensure that: it is as easy as possible for a member of the public to make a complaint to us; we treat as a complaint any clear expression of dissatisfaction with our operations which calls for a response; we treat every complaint seriously, whether it is made by telephone, letter, email or in person; we deal with every complaint quickly and politely; we respond to complaints in the appropriate manner; and we learn from complaints, use them to improve, and monitor them at our charity trustee meetings. What to do if you have a complaint If you have a complaint about the Charity’s fundraising activities, you can contact the Charity in writing or by telephone at [email protected] or Marketing Department, Dublin Zoo, Phoenix Park, Dublin 8, 01 4748900 In the first instance, your complaint will be dealt with the Marketing Manager. Please give us as much information as possible and provide us with your relevant contact details. What happens next? If you complain in person or over the phone, we will try to resolve the issue there and then. -

Zoo Agent's Measure in Applying the Five Freedoms Principles for Animal Welfare

Veterinary World, EISSN: 2231-0916 RESEARCH ARTICLE Available at www.veterinaryworld.org/Vol.10/September-2017/3.pdf Open Access Zoo agent’s measure in applying the five freedoms principles for animal welfare Argyo Demartoto, Robertus Bellarminus Soemanto and Siti Zunariyah Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia. Corresponding author: Argyo Demartoto, e-mail: [email protected] Co-authors: RBS: [email protected], SZ: [email protected] Received: 04-04-2017, Accepted: 04-08-2017, Published online: 05-09-2017 doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2017.1026-1034 How to cite this article: Demartoto A, Soemanto RB, Zunariyah S (2017) Zoo agent’s measure in applying the five freedoms principles for animal welfare, Veterinary World, 10(9): 1026-1034. Abstract Background: Animal welfare should be prioritized not only for the animal’s life sustainability but also for supporting the sustainability of living organism’s life on the earth. However, Indonesian people have not understood it yet, thereby still treating animals arbitrarily and not appreciating either domesticated or wild animals. Aim: This research aimed to analyze the zoo agent’s action in applying the five freedoms principle for animal welfare in Taman Satwa Taru Jurug (thereafter called TSTJ) or Surakarta Zoo and Gembira Loka Zoo (GLZ) of Yogyakarta Indonesia using Giddens structuration theory. Materials and Methods: The informants in this comparative study with explorative were organizers, visitors, and stakeholders of zoos selected using purposive sampling technique. The informants consisted of 19 persons: 8 from TSTJ (Code T) and 10 from GLZ (Code G) and representatives from Natural Resource Conservation Center of Central Java (Code B). -

Kruger National Park Elephant Management Plan

Elephant Management Plan Kruger National Park 2013-2022 Scientific Services November 2012 Contact details Mr Danie Pienaar, Head of Scientific Services, SANParks, Skukuza, 1350, South Africa Email: [email protected], Tel: +27 13 735 4000 Elephant Management Kruger Authorisation This Elephant Management Plan for the Kruger National Park was compiled by Scientific Services and the Kruger Park Management of SANParks. The group represented several tiers of support and management services in SANParks and consisted of: Scientific Services Dr Hector Magome Managing Executive: Conservation Services Dr Peter Novellie Senior General Manager: Conservation Services Dr Howard Hendricks General Manager: Policy and Governance Mr Danie Pienaar Senior General Manager: Scientific Services Dr Stefanie Freitag-Ronaldson General Manager: Scientific Services Savanna & Arid Nodes Dr Sam Ferreira Scientist: Large Mammal Ecology Kruger Park Management Mr Phin Nobela Senior Manager: Conservation Management Mr Nick Zambatis Manager: Conservation Management Mr Andrew Desmet Manager: Guided Activities and Conservation Interpretation Mr Albert Machaba Regional Ranger: Nxanatseni North Mr Louis Olivier Regional Ranger: Nxanatseni South Mr Derick Mashale Regional Ranger: Marula North Mr Mbongeni Tukela Regional Ranger: Marula South Ms Sandra Basson Section Ranger: Pafuri Mr Thomas Mbokota Section Ranger: Punda Maria Mr Stephen Midzi Section Ranger: Shangoni Ms Agnes Mukondeleli Section Ranger: Vlakteplaas Mr Marius Renkin Section Ranger: Shingwedzi Ms Tinyiko -

See the Light Inside Hellabrun Zoo’S Discovery Cave

QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA WINTERZ 2016 OO QUARIAISSUE 95 SEE THE LIGHT INSIDE HELLABRUN ZOO’S DISCOVERY CAVE To Russia with love REINTRODUCING THE PERSIAN LEOPARD 1 1 Majestic markhors AN EEP UPDATE FROM HELSINKI ZOO Contents Zooquaria Winter 2016 14 16 26 4 From the Director’s chair 18 Interview Our Director reports from the IUCN World Zooquaria talks to the outgoing and new Chairs of Conservation Congress the IUCN Species Survival Commission, Simon Stuart and Jon Paul Rodriguez 5 Noticeboard News from the world of conservation 21 Endangered species A creative solution that is helping to save the white- 6 Births & hatchings footed tamarin Magpies, foxes and turaco join the list of breeding successes 22 Conservation partners The benefits of collaboration between EAZA and 8 EAZA Annual Conference ALPZA EAZA’s annual conference is defined by its optimism for the future 23 EEP report Helsinki Zoo reports on the status and future of its 10 WAZA Conference Markhors EEP Why zoos and aquariums must be agents for change 24 Horticulture 11 EU Zoos Directive Planting ideas and solutions in action at Dublin Zoo How EAZA Members can take part in defining the future of the EU Zoos Directive. 26 Exhibits How the Discovery Cave at Hellabrun Zoo is helping 12 Campaigns visitors to overcome their phobias The Let It Grow campaign can help to demonstrate the importance of conserving local species 28 Education Can television and social media offer the same 14 Breeding programmes educational experience as a visit to the zoo? Reintroducing the Persian Leopard in the Caucasus 30 Resources 16 Conservation A visit to the ZSL Library will prove both informative How a combination of conservation initiatives and and inspiring research projects have helped to save the white stork Zooquaria EDITORIAL BOARD: EAZA Executive Office, PO Box 20164, 1000 HD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. -

Danish Zoo Defends Lion Killing After Giraffe Cull 26 March 2014, by Jan M

Danish zoo defends lion killing after giraffe cull 26 March 2014, by Jan M. Olsen "Furthermore we couldn't risk that the male lion mated with the old female as she was too old to be mated with again due to the fact that she would have difficulties with birth and parental care of another litter," the zoo said. The cubs were also put down because they were not old enough to fend for themselves and would have been killed by the new male lion anyway, officials said. Zoo officials hope the new male and two females born in 2012 will form the nucleus of a new pride. They said the culling "may seem harsh, but in nature is necessary to ensure a strong pride of This is a Sunday, Feb. 9, 2014 file photo of the carcass lions with the greatest chance of survival." of Marius, a male giraffe, as it is eaten by lions after he was put down in Copenhagen Zoo . The zoo that faced In February, the zoo faced protests and even death protests for killing a healthy giraffe to prevent inbreeding threats after it killed a 2-year-old giraffe, citing the says it has put down four lions, including two cubs, to need to prevent inbreeding. make room for a new male lion. Citing the "pride's natural structure and behavior," the Copenhagen Zoo This time the zoo wasn't planning any public said Tuesday March 25, 2014 that two old lions had dissection. Still, the deaths drew protests on social been euthanized as part of a generational shift. -

Conservazione Ed Etica Negli Zoo “Dopo Marius”

703 Etica & Politica / Ethics & Politics, XX, 2018, 3, pp. 703-729. ISSN: 1825-5167 CONSERVAZIONE ED ETICA NEGLI ZOO “DOPO MARIUS” LINDA FERRANTE Università di Padova Dipartimento di Biomedicina Comparata e Alimentazione [email protected] BARBARA DE MORI Università di Padova Dipartimento di Biomedicina Comparata e Alimentazione [email protected] ABSTRACT The case of Marius, a young giraffe suppressed in the name of species conservation in February 2014 at Copenhagen Zoo as a surplus, created both considerable media outcry and heated debate both in science and ethics. Debate that even today, after almost 5 years still has not subsided. In this contribution, we try to confront with the reiterated question ‘are zoos unethical?’, discussing ‘from the inside’ the presuppositions of specie conservation in zoos today. Following the main questions that have been raised on the web regarding the case of Marius, we suggest that in ethical relevant issues as Marius’ case, a standardized and contextualized ethical analysis on a case-by-case basis can be of help. By clarifying assumptions, considering the values at stake, the scientific aspects and the needs of the stakeholders involved, it is possible to improve the ethical decision-making process. This process can favor the transparency and consistency of the work of the zoos. The request for standardized ethical assessments through ethics committees and the use of tools for analysys has already emerged in different zoological context. If they want to continue to have support from society, it is mandatory for modern zoos to make a commitment to take directly into consideration the difficulties and uncertainties that distinguish the new social ethics for animals.