T.S.Catalogueweb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

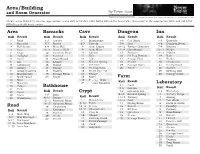

Area-Building and Room Generator

Area/Building By Trevor Scott and Room Generator neverengine.wordpress.com This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Create areas fileld with various, appropriate rooms with a few dice rolls! Roll a d20 on the Area table, then move to the appropriate table and roll a few d20s to generate some rooms. Area Barracks Cave Dungeon Inn Roll Result Roll Result Roll Result Roll Result Roll Result 1 Road 1-3 Armory 1-5 Mushrooms 1-6 Cell Block 1-3 Quarters 2 Barracks 5-7 Bunks 6-7 Cave-In 7-9 Hole 4-6 Common Room 3 Bathhouse 8-9 Mess Hall 8 Area: Crypts 10-12 Torture Chamber 7-9 Kitchen 4 Cave 10-11 Practice Hall 9 Area: Mine 13-14 Guardhouse 10-11 Shrine 5 Crypt 12 Common Room 10 Garden 15 Furnace 12-13 Stables 6 Dungeon 13 Furnace 11 Hole 16 Pit Trap Bottom 14 Bath 7 Farm 14 Guardhouse 12 Lake 17 Sewage Flow 15 Bunks 8 Inn 15 Kennel 13 Natural Spring 18 Shrine 16 Cloakroom 9 Laboratory 16 Shrine 14 Ore Vein 19 Storage Room 17 Dining Room 10 Library 17 Smithy 15 Pit Trap Bottom 20 Tomb 18 Garden 11 Living Quarters 18 Stables 16 Secret Passage 19 Meeting Hall 12 Manufactory 19 Storage Room 17 Sewage Flow 20 Storage Room 13 Marketplace 20 Study 18 Shrine Farm 14 Mine 19 Storage Room Roll Result 15 Museum 20 Torture Chamber Laboratory Palace 1-4 Field 16 Bathhouse Roll Result 17 Park Sample file 5-6 Garden 18 Sewer Roll Result Crypt 7-8 Livestock Pen 1-2 Workshop 1-8 Bath 9-10 Natural Spring 3 Archery Range 19 Slum Roll Result 20 Warehouse 9-11 Sauna 11-12 Tannery 4 Armory 12-13 -

Woottonbrookwombourne

WoottonbrookWOMBOURNE A beautiful collection of 1,2,3 & 4 bedroom homes and apartments 1 ith idyllic streets, quaint houses and handy shops, Wif you’re looking to relocate, Wombourne makes for an attractive and welcoming place. With its three main streets around a village green, it’s a beautiful South Staffordshire gem, with a quirky reputation for claiming to be England’s largest village. Just four miles from Wolverhampton, you won’t be short on things to do. Surrounded by countryside, it’s a rambler’s paradise. There’s the scenic Wom Brook walk or a Sunday afternoon amble up and down the South Staffs Railway Walk. There’s also Baggeridge Country Park, a mere 2.5 miles away by car. If it’s jogging, cycling or even fishing, you have the Staffordshire and Worcestershire canal on your Country Life doorstep too. Woottonbrook by Elan Homes is nestled in a quiet, rural location only five minutes away from Wombourne village. A mixture of bright, spacious and contemporary 1,2,3 & 4 bedroom homes and apartments effortlessly blends rural and urban life. Welcome to your future. 2 A lot of love goes into the building of an Elan home - and it shows. We lavish attention on the beautifully crafted, traditionally styled exterior so that you don’t just end up with any new home, but one of outstanding style and real character. Then, inside, we spread the love a little bit more, by creating highly contemporary living spaces that are simply a pleasure to live in. Offering light, airy, high specification, luxury accommodation that has the flexibility to be tailored to the individual wants and needs of you and your family. -

By Joseph Aquino December 17, 2019 - New York City

New York’s changing department store landscape - by Joseph Aquino December 17, 2019 - New York City Department stores come and go. When one goes out of business, it’s nothing unusual. But consider how many have gone out of business in New York City in just the past generation: Gimbels, B. Altman, Mays, E. J. Korvette, Alexanders, Abraham & Straus, Gallerie Lafayette, Wanamaker, Sears & Roebuck, Lord & Taylor, Bonwit Teller, and now Barneys New York—and those are just the ones I remember. The long-time survivors are Bloomingdale’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, Bergdorf Goodman and Macy’s. The new kids on the block are Nordstrom (which has had a chance to study their customer since they have operated Nordstrom Rack for some time) and Neiman-Marcus, which has opened at Hudson Yards with three levels of glitz, glam, luxury, and fancy restaurants. It’s unfortunate to see Lord & Taylor go, especially to be taken over by a group like WeWork, which has been on a meteoric rise to the top of the heap and controls a lot of office space. I was disappointed at this turn of events but I understood it, and was not surprised. Lord & Taylor had the best ladies’ department (especially for dresses) in Manhattan. I know, because I try to be a good husband, so I shop with my wife a lot! But that was a huge amount of space for the company to try to hold onto. Neither does the closing of Barneys comes as any shock. I frequented Fred’s Restaurant often and that was the place to see and be seen. -

THE SINGLETON Plots 293, 316, 317, 318, 319, 330 & 331 GROUND FLOOR FIRST FLOOR

THE SINGLETON Plots 293, 316, 317, 318, 319, 330 & 331 GROUND FLOOR FIRST FLOOR Living/ Living/ Bathroom Bathroom Dining Area Dining Area Bedroom 2 Bedroom 2 W C C W En- En- suite suite C C Kitchen Kitchen Master Master WC WC Bedroom Bedroom W W Kitchen 2.88 x 2.33m 9’5” x 7’8” Master Bedroom 3.97 x 2.76m 13’0” x 9’1” Key: C - Cupboard W - Wardrobe Living/Dining Room 4.81 x 4.63m 15’9” x 15’2” Bedroom 2 3.27 x 2.51m 10’9” x 8’3” W - Space for wardrobe THE SINGLETON SPECIFICATION BEAUTIFULLY DESIGNED KITCHENS • Mains fed carbon monoxide detector, positioned • Contemporary kitchen designs adjacent to gas boiler • Soft close doors and drawers • 10 year NHBC Buildmark Warranty, including 2 year defect and emergency out of hours cover • Laminate worktop and upstand • One and half bowl stainless steel sink, with mono sink mixer tap by Vado EXTERNAL • Electrolux stainless steel single oven • Timber external entrance door with multi-point locking system • Ceramic hob with pull out extractor hood • UPVC double glazed windows with french • Integrated Electrolux dishwasher A+ doors to living and kitchen / dining • Integrated Electrolux 70/30 split fridge/freezer A+ • Closeboard fencing to rear gardens • Integrated Zanussi Washing/Dryer A • Landscaped front gardens and turfed rear gardens • Paved paths and patio areas STYLISH BATHROOMS • External tap in rear garden • Contemporary white sanitaryware, with chrome accessories by Vado HEATING, ELECTRICAL & LIGHTING • Floor standing concealed cistern WC • Energy efficient Vaillant combination boiler • -

Ref : E034078n Office Premises

3 Cornhill, Ottery St Mary, Devon, t 01404 813762 e [email protected] EX11 1DW f 01404 815236 devon and dorset OFFICE PREMISES REF : E034078N ST SAVIOURS overlooking the attractive Millennium Green with its EXETER ROAD riverside walk. At the time of our inspection the building was next to the 'The Station', home of Ottery town OTTERY ST MARY council, other businesses close by comprising RIO DEVON, EX11 1RE (Recycling In Ottery), Carpets Collect, Alansway Body Repairs and other motor vehicle repair and sales businesses. In one direction the town centre, with its Sainsbury's supermarket, is only a short walk away whilst in the other direction can be found Alansway business park, the local hospital, school and residential housing with new residential developments currently in the course of construction. AREA Ottery St Mary nestles in the attractive Otter Valley, surrounded by countryside of outstanding natural beauty, supports a good size resident population with numerous new housing developments having taken place over the years and other major developments in the course of construction, renowned for its 'Kings' secondary school with additional trade drawn from the many surrounding villages, hamlets and farming communities, The popular regency coastal resort of VIEWING STRICTLY BY PRIOR APPOINTMENT Sidmouth lies approximately 6 miles away whilst the THROUGH THE SELLING AGENTS EVERETT expanding City of Exeter, together with airport, mainline MASSON AND FURBY 01404 813762 railway station, and M5 motorway network lies approximately 12 miles, quickly reached via the nearby Prominent easily accessible premises A30 dual carriageway. Versatile first floor space, approx. 1,800 sq.ft. -

ENTRANCE HALL Stairs to First Floor, Radiator, Alarm System

ENTRANCE HALL Stairs to first floor, radiator, alarm system. CLOAKROOM WC, pedestal wash hand basin, extractor fan, radiator, tiled floor. KITCHEN/DINER 33' 3" x 13' 9" (10.16m x 4.2m) Single window to front, three windows to side, French doors to rear, range of white gloss high and low level cupboard units, marble worktop, inset sink with mixer tap, five ring gas hob with extractor fan over, integrated oven, integrated NEFF dishwasher, integrated fridge and wine cooler, island, storage cupboard under the stairs, tiled floor. UTILITY ROOM Door to rear garden, high and low level white gloss cupboard units, marble worktop, stainless steel sink with mixer tap, plumbing for washing machine, tiled floor. LOUNGE 21' 9" x 11' 3" (6.65m x 3.45m) Window to front, bi-folding doors across the full width at the back leading to the garden. FIRST FLOOR LANDING Window, radiator, airing cupboard housing hot water cylinder. MASTER BEDROOM 13' 6" x 10' 11" (4.12m x 3.34m) Windows to front and side, dressing area with built in wardrobe with sliding mirrored doors, ensuite. ENSUITE 10' 6" x 4' 6" (3.21m x 1.38m) Window to side, WC with concealed cistern, pedestal wash hand basin with mixer tap, large shower cubicle, heated towel rail, tiled floor. BEDROOM TWO 13' 5" x 10' 9" (4.11m x 3.3m) Window to front, ensuite, radiator. ENSUITE 7' 4" x 5' 1" (2.25m x 1.57m) Window to side, WC with concealed cistern, wash hand basin with mixer tap, shower cubicle, mirrored wall cabinet, extractor fan, heated towel rail, tiled floor. -

LBC Risk Assessment. Covid Specific. 06.8.20

Summary of LBC Risk Assessment (Covid Specific) 05.05.21 LBC Risk Assessment 2020 in place. Controlled opening of the Centre bookshop, reception, limited meditation and yoga classes. Maximum number of people at any event in the main shrine room 26 (10 Team, 16 participants), in Breathing Space 14 (2 team, 12 participants). Government guidance on re-opening of places of worship is available here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-for-the-safe-use-of-places-of-worship-from-4-july Government guidance on working safely in shops is available here: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/working-safely-during-coronavirus-covid-19/shops-and-branches Government guidelines for safer travel is here: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-safer-travel-guidance-for-passengers What are the Persons at Actions taken hazards? risk? Virus transmission Public / Team ● 2 metre markings outside the Centre around entrance to Members ● Centre doors open 20 minutes before the activity is due to start centre ● Team member in Courtyard to welcome and guide people as necessary ● Cleaning door handles and exit buttons daily ● Signage reminding everyone to wash hands on entry and exit, and hand sanitiser provided Virus transmission Public, Centre ● Mitigated through social distancing (SD), good ventilation and limiting numbers of people at the through the air within Workers and centre at any one time centre Team ● Good signage in place reminding people of SD Members ● Receptionist and team members wearing visor / face coverings ● All members of public wearing face coverings when indoors at the LBC, in all areas ● Team and volunteers trained prior to opening /event ● The Centre will report any instances of someone who has been working or the attending getting Covid 19: [email protected] ● The Centre will do all it can to support the Test and Trace programme as necessary. -

Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1998 Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration Patricia E. Mears Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Mears, Patricia E., "Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration" (1998). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 191. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/191 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration by Patricia E. Mears Jessie Franklin Turner was an American couturier who played a prominent role in the emergence of the high-fashion industry in this country, from its genesis in New York during the First World War to the flowering of global influence exerted by Hollywood in the thirties and forties. The objective of this paper is not only to reveal the work of this forgotten designer, but also to research the traditional and ethnographic textiles that were important sources of inspiration in much of her work. Turner's hallmark tea gowns, with their mix of "exotic" fabrics and flowing silhouettes, evolved with the help of a handful of forward-thinking manufacturers and retailers who, as early as 1914, wished to establish a unique American idiom in design. -

Convention Center Hotel Nears Completion PAGE J2 Courtyard by Marriott in Downtown Sioux City to Feature 151 Rooms

INDUSTRY SUNDAY, MARCH 17, 2019 | siouxcityjournal.com | SECTION I Today, in its annual Progress edition, The Journal continues a series of special sections over fi ve Sundays that detail new development in the tri-state region. Sections I and J today focus on a bevy of industrial and housing projects. TIM HYNDS PHOTOS, SIOUX CITY JOURNAL Developer to restore Warrior Hotel and Davidson Building developers Renee and Lew Weinberg, left, talk with Restoration St. Louis’ Amy and Amrit Gill prior to a three historic buildings in ceremonial ribbon cutting held Tuesday, Feb. 5, 2019, in what will become the second-story lobby area of the Warrior Hotel in downtown Sioux City. The long-empty historic hotel and the adjacent Davidson Building are being remodeled into hotel, apartment and retail spaces. Sioux City. HISTORIC WARRIOR gets extensive facelift Ho-Chunk Inc.’s Flatwater DOLLY A. BUTZ Crossing in South Sioux [email protected] enters next phases. SIOUX CITY — Plans to restore the War- rior Hotel to its former glory have come and gone over the past 40 years, but this time, PAGE I5 Amy and Amrit Gill, owners of Restoration St. Louis, say rehabilitation of the historic building is a “done deal.” The humming of construction equipment echoed through the Warrior on a Monday af- ternoon in early February as the Gills toured the historic hotel. A buck hoist, a temporary elevator, was being put in place to transport materials to each fl oor of the Warrior, and demolition work was ongoing in the next- door Davidson Building. First units sold in Sioux “When you do a hotel like this with Mar- City’s Chestnut Hill riott’s blessing, it can’t look like anything People leave the former Warrior Hotel following a ceremonial ribbon cutting Feb. -

Bonwit Teller's First Female President, 1934-1940 Michael Mamp

Charlotte, North Carolina 2014 Proceedings Hortense Odlum: Bonwit Teller’s first female president, 1934-1940 Michael Mamp, Central Michigan University, USA; Sara Marcketti, Iowa State University, USA Keywords: Hortense Odlum, Bonwit Teller, retail, history From the late 19th century onward, a myriad of new retail stores developed within the United States. These establishments provided shoppers, particularly women, assortments of fashion products that helped shape the American culture of consumption. Authors have explored the role that women played as consumers and entry-level saleswomen in department stores in both America and abroad.1 However, aside from scholarship regarding Dorothy Shaver and her career at Lord & Taylor, little is known about other female leaders of retail companies. Shaver is documented as the first female President of a major American retail company and the “first lady of the merchandising world.”2 However, Hortense Odlum, who served as first President and then Chairwoman of Bonwit Teller from 1934-1944, preceded Shaver by ten years.3 Furthermore, although Bonwit Teller operated for close to a hundred years (1895-1990), the history of the store remains somewhat obscure. Aside from brief summaries in books that speak to the history of department stores, no comprehensive history of the company exists. A historical method approach was utilized for this research. Primary sources included Odlum’s autobiography A Woman’s Place (1939), fashion and news press articles and advertisements from the period, archival records from multiple sources, and oral history.4 The use of multiple sources allowed for the validation of strategies noted in Odlum’s autobiography. Without previous management or business knowledge, Odlum approached her association with the store from the only perspective she really knew, that of a customer first who appreciated quality, style, service, and friendliness.5 She created an environment that catered to a modern woman offering products that would be appreciated, truly a Woman’s Place. -

DONALD TRUMP REFLECTS on HIS BEGINNINGS, VENTURES, and PLANS for the FUTURE Donald Trump Chairman and President the Trump Organ

DONALD TRUMP REFLECTS ON HIS BEGINNINGS, VENTURES, AND PLANS FOR THE FUTURE Donald Trump Chairman and President The Trump Organization December 15, 2014 Excerpts from Mr. Trump's Remarks Are you considering running for President? I am considering it very strongly. How did you get started in business, buying a hotel, with almost no money? Well, it was owned by the Penn Central Railroad and it was run by some very good people. Actually, it's very interesting, because he happens to be a very good man. It was Victor Palmieri and Company. And one of the people is John Koskinen. Does anyone know John Koskinen? He's the head of the IRS. And he's a very good man. And while I'm a strong conservative and a strong Republican, he's a friend of mine. And he did a great job running Victor Palmieri. And I made deals with John and the people at Victor Palmieri and took options to the building. And after I took options to the Commodore, I then went to the city. Because the city was really in deep trouble. I was about 28 years old, and the city was really in trouble. And I said look, you're going to have to give me tax abatement. Otherwise this was never going to happen. Then I went to Hyatt. I said you guys put up all the money and I'll try and get the approvals. And I got all the approvals. And Hyatt, Jay Pritzker and the Pritzker family, they put up the money. -

Offering Memorandum 4Th & Jackson | Of�Ce Condos 700 4Th St, Sioux City, IA 51101 for Sale Of�Ce Building 12,751 SF | $1,174,725

For Sale Ofce Building 12,751 SF | $1,174,725 Offering Memorandum 4th & Jackson | Ofce Condos 700 4th St, Sioux City, IA 51101 For Sale Ofce Building 12,751 SF | $1,174,725 Table of Contents 4 Section 1 Location Information 11 Section 2 Property Information 19 Section 3 Demographics For Sale Ofce Building 12,751 SF | $1,174,725 SALE PRICE: $1,174,725 Property Overview NUMBER OF UNITS: 4 100% leased office condo investment in the heart of Siouxland's entertainment district. The sale includes CAP RATE: 8.0% the first two floors, consisting of units 100, 200, 210 & 220. GRM: 6.8 NOI: $93,978 Featuring lots of natural light and great views down Historic Fourth, the entire building has been remodeled LOT SIZE: 2.6 Acres and converted to Class A space. The building has direct 4th floor and skywalk level accesses to the BUILDING SIZE: 12,751 SF adjacent Heritage Parking Ramp and direct skywalk access to the Sioux City Convention Center, Marriott BUILDING CLASS: A Courtyard, Mercy One, Orpheum Theatre & Historic Pearl. Also adjacent is the Promenade 14 Cinema & YEAR BUILT: 1972 RENOVATED: 2020 Marto Brewing. ZONING: DC MARKET: Sioux City, IA Building naming rights facing I-29 are available for future non-financial anchor tenant. Sale includes seller's SUB MARKET: Downtown installation of a $115,000 HVAC system on main floor prior to closing, which will reduce annual repair CROSS STREETS: 4th St & Jackson St costs. TRAFFIC COUNT: 10,400 400 Gold Circle, Suite 120 Dakota Dunes, SD 57049 712 224 2727 tel naiunited.com 4th & Jackson | Ofce Condos 700 4th