Problems and Limitations in Using Psychological Assessment in the Contemporary Health Care Delivery System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphologist

Confessions of a (Former) Graphologist A first-hand report of one man's entry into the field of graphology, his later deep involvement with the practice, and his subsequent disillusionment. Along the way he encountered a continuing lack of scientific validation and a refusal of graphologists to face graphology's validity problems. ROBERT J. TRIPICIAN round 1972 I happened upon a magazine article describing handwriting analysis. The article got my A immediate attention as it showed a sample of hand- writing that closely resembled that of a co-worker. The per- sonality factors described in the analysis of this sample appeared to match the co-worker's personality very closely. This piqued my interest. After retirement I pursued the study and practice of graphology rather heavily, even becoming a Certified Professional Graphologist. I soon found that while texts on the subject are in general agreement regarding the meaning and interpretation of individual handwriting features, none of them describe an orderly approach to developing a com- 4 4 January/February 2000 SKEPTICAL INQUIRER plete profile. Indeed, developing profiles is described as an eso- with a sharp point denotes a sharp temper. teric and intuitive process. Furthermore, none of the texts d. A lower case p with a spike at the top (see figure 4) is describe an orderly method of recording notes. interpreted to mean that the writer is argumentative. However, I subsequently developed a computer database to automate as in the case of the capital letter /, this formation was taught the note-taking process and eliminate die need for memoriz- in both the Mills and Palmer Method systems as the standard. -

Psychological Tests Commonly Used in the Assessment of Chronic Pain *

Colorado Division of Workers’ Compensation COMPREHENSIVE PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING Psychological Tests Commonly Used in the Assessment of Chronic Pain * TEST TEST CHARACTERISTICS STRENGTHS AND LENGTH, SCORING WEAKNESSES OPTIONS & TEST TAKING TIME Comprehensive Inventories For Medical Patients BHI™ 2 (Battery for What it Measures: Depression, anxiety and hostility; Strengths: Well-developed theoretical basis tied 217 items, 18 scales including Health Improvement – 2nd violent and suicidal ideation; borderline, emotional to a paradigm of delayed recovery in medical 3 validity measures, 40 edition ) dependency, chronic maladjustment, substance abuse, patients, and to assessing primary (“red flag”) content-based subscales, 25 history of abuse, perseverance, conflicts with and secondary (“yellow flag”) risk factors. Has critical items, 25-35 minutes, Pearson Assessments employer, family and physician, pain preoccupation, nationally normed 0-10 pain profiling. Two computerized scoring and www.pearsonassessments.c somatization, disability perceptions and others. norms groups are available, based on national report. om rehabilitation patient and community samples, Uses: Useful for identifying affective, both of which are stratified to match US census 6th grade reading level Standardization: S characterological, psychophysiological and social data. English and Spanish versions available. Scientific Review: JBG factors affecting pain and disability reports. Also Standardized audio tape administration for Intended for: M useful for assessing patients -

List of Psychological Tests Material Was Prepared for Use As an Aid in Handling Requests for Psychological Testing

List of Psychological Tests Material was prepared for use as an aid in handling requests for psychological testing. The minutes allocated for each test include administration, scoring and write up. Determination of the medical necessity of psychological tests always requires consideration of the clinical facts of the specific case to assure that tests given are a cost-effective means of determining the appropriate treatment for the individual patient and are related to the diagnosis and treatment of covered mental health conditions. INSTRUMENT TYPE AGE MINUT COMMENTS ES 16 Personality Factor Questionnaire (16-PF) Personality 16+ 30 35-60 min per Tests in Print for admin time only ABEL Screen Sexual Interest Adol + 120 Primarily forensic in nature: may not be covered Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment 60 Preschool Module Behav Rating Scale 1.5-5 10 Caregiver-Teacher Report Form Behav Rating Scale 1.5-5 10 Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Behav Rating Scale 1.5-5 15 Teacher Report Form Behav Rating Scale 6-18 20 Youth Self-Report (YSR) Behav Rating Scale 11-18 20 ACTeERS-ADD-H Comprehensive, Teachers Rating Scale Behav Rating Scale 5 – 13 15 Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS II) Behav Rating Scale 0-89 30 Adaptive Behavior Scale (ABS) Developmental 3-18 30 ADHD Rating Scale Behav Rating Scale 4 – 18 15 Adolescent Anger Rating Scale Behav Rating Scale 11-19 15 Adolescent Apperception Cards Projective Personality 12 – 19 60 Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL) Behav Rating Scale 18-89 30 Admin. Time 20 min. + 10 min. for scoring, interpretation, write up. Adolescent Psychopathology Scale Personality Child-adult 60 Alzheimer’s Quick Test (AQT) Neuro Adult 10 Amen System Checklist Behav Rating Scale Adult 15 Animal Naming Neuro Child-adult 10 Aphasia Screening Test (Reitan Indiana) Neuro 5+ 30 Asperger’s Syndrome Diagnostic Scales (ASDS) Rating scale 5-18 20 Attention Deficit Disorder Eval. -

Online Psychological Testing

Online psychological testing APS Tests and Testing Expert Group August 2018 This resource was developed by Peter Macqueen, Wally Howe and Marian Power as members of the Tests and Testing Expert Group. Copyright © 2014 Online psychological testing Table of Contents 1. Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Factors driving the increasing use of online testing ..................................................................... 5 3. Usage of online testing ............................................................................................................................. 6 3.1 Organisational settings ................................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Educational and other settings .................................................................................................... 6 4. Standards, guidelines and good practice .......................................................................................... 7 5. Advantages of online testing (over traditional or paper and pencil testing) ..................... 9 6. Issues and potential disadvantages of online testing ...............................................................10 7. Technical issues .........................................................................................................................................11 8. Ethics ...............................................................................................................................................................12 -

Psychological and Neuropsychological Testing

2018 Level of Care Guidelines Psych & Neuropsychological Testing Psychological and Neuropsychological Testing Introduction: The Psychological and Neuropsychological Testing Guidelines is a set of objective and evidence-based behavioral health 2 criteria used to standardize coverage determinations, promote evidence-based practices, and support members’ recovery, resiliency, and well-being. The Psychological and Neuropsychological Testing Guidelines is derived from generally accepted standards of practice for psychological and neuropsychological testing. These standards include guidelines and consensus statements produced by professional specialty societies, as well as guidance from governmental sources such as CMS’ National Coverage Determinations (NCDs) and Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs). The Psychological and Neuropsychological Testing Guidelines is also derived from input provided by clinical personnel, providers, professional specialty societies, consumers, and regulators. Optum is a brand used by Behavioral Health and its affiliates. The term “member” is used throughout the Psychological and Neuropsychological Testing Guidelines. The term is synonymous with “consumer” and “enrollee”. It is assumed that in circumstances such as when the member is not an emancipated minor or is incapacitated, that the member’s representative should participate in decision making and treatment to the extent that is clinically and legally indicated. The terms “recovery” and “resiliency” are used throughout the Psychological and Neuropsychological -

The Legal Implications of Graphology

Washington University Law Review Volume 75 Issue 3 January 1997 The Legal Implications of Graphology Julie A. Spohn Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Recommended Citation Julie A. Spohn, The Legal Implications of Graphology, 75 WASH. U. L. Q. 1307 (1997). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol75/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LEGAL IMPLICATIONS OF GRAPHOLOGY I. INTRODUCTON Graphology, "the alleged science of divining personality from handwriting,"1 is for many American employers a tool for making various employment decisions. In recent years, American employers' use of graphology in employment decisions has increased.2 Today, about six thousand American companies report using graphology;3 however, this 1. Joe Nickell, A Brief History of Graphology, in THE WRITE STUFF: EVALUATIONS OF GRAPHOLOGY, THE STUDY OF HANDWRITING ANALYSIS 23, 23 (Barry L. Beyerstein & Dale F. Beyerstein eds., 1992). Writers sometimes use the term "graphology" interchangeably with "graphoanalysis" or "handwriting analysis." However, "graphoanalysis" refers only to the type of graphology practiced by Graphoanalysts, a trademarked name for graduates of Chicago's International Graphoanalysis Society. See id. at 21-22. This Note uses the term "graphology" to refer to graphology in general and to distinguish graphology from the handwriting analysis that questioned document examiners use to identify handwriting in forgeries and other cases. -

Medical Policy Neuropsychological and Psychological Testing

Medical Policy Neuropsychological and Psychological Testing Table of Contents • Policy: Commercial • Coding Information • Information Pertaining to All Policies • Policy: Medicare • Description • References • Authorization Information • Policy History Policy Number: 151 BCBSA Reference Number: N/A Related Policies N/A Policyi Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Neuropsychological Testing Neuropsychological testing is MEDICALLY NECESSARY when conditions are met using McKesson InterQual® criteria for medical necessity reviews. Neuropsychological testing for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) may be MEDICALLY NECESSARY for the following: • when routine treatment for ADHD has not improved patient outcomes and there is well documented evidence of treatment failure, and • when psychological testing has been completed and further clinical information is needed to rule out a medical or psychiatric diagnosis. Neuropsychological testing for the routine diagnosis of ADHD is NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY. Neuropsychological testing is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY when used primarily for: • educational or vocational assessment or training (to diagnose specific reading disorders, developmental disorders of scholastic skills, dyslexia and alexia), or • determining eligibility for special needs programs, • assessment or diagnosing of pervasive developmental disorders or other disorders or psychological development, • improving academic performance, • baseline assessment of function, • monitoring of chronic -

Psychological/Neuropsychological Testing Request (All Information Requested on This Form Must Be Complete

Psychological/Neuropsychological Testing Request (All information requested on this form must be complete. Missing data may result in authorization delay.) • Submission of this information by fax or phone does not constitute authorization of services. Blue Cross of Idaho’s Healthcare Operations department will notify you of their decision by fax, mail, phone or portal. • Authorization period may not exceed one month without review of medical records. If medical necessity justifies special handling, please include an explanation. • All psychological testing requests must include a diagnostic assessment completed within the last 30 days by a behavioral health professional as well as at least one validated symptom inventory or rating scale. Your request will not be processed without this documentation. • For questions regarding this form, please call 208-331-7535 or 800-743-1871. • Submit all elective prior authorization requests at least 10 days prior to the scheduled date of service. • If the request is URGENT please check here: q Reason for Urgent: ______________________________________________________ q Behavioral Health: Fax 208-387-6840 PLEASE PRINT OR TYPE ONLY Requesting Provider: Provider ID: Date: Office Address: Tax ID Number: Contact Person: Phone: Fax: Patient Name: Enrollee ID: Date of Birth: Testing Provider Information: Name/Credentials: Provider ID: Address: Email address: Phone: Fax: Service Request Request Type: q Psychological q Neuropsychological Number of units requested by CPT Code: PT: 96105:____ 96125:____96110:____ -

Neuropsychological Testing (NPT) Vs. Psychological Testing

Neuropsychological Testing (NPT) vs. Psychological Testing Psychological tests assess a range of mental abilities and attributes, including achievement and ability, personality, and neurological functioning. They allow for an assessment of a patient's cognitive and behavioral functioning and an analysis of changes related to mental or physical disease, injury, or abnormal development of the brain. Psychological and Neuropsychological tests provide a standardized means of sampling behavior, an objective method for evaluating responses, and a tool for comparing the functioning of an individual with peers. Neuropsychological Testing (NPT) NPT is an objective evaluation of mental cognitive, motor and behavioral function and is not a mental health evaluation. This testing may be used to augment a comprehensive medical history and physical examination, as well as a neurological investigation of certain conditions. MHS considers NPT medically necessary when provided to aid in the assessment of cognitive impairment due to medical condition such as, but not limited to: • Traumatic brain injury, Stroke, or • Differential diagnosis between Psychogenic Neurosurgery or relating to a medical and Neurogenic Syndromes when combined diagnosis, such as Epilepsy, Hydrocephalus, with clinical, laboratory, and imaging data, AIDS, Brain Tumor, Cerebral Anoxic or may assist in determining a diagnosis Hypoxic Episode, Central Nervous System • When there is a need to quantify the patient's Infection (CNS), Neoplasms or Vascular deficits, particularly when the -

Jurnal Ilmu Komputer Dan Informasi (Journal of Computer Science and Information)

Jurnal Ilmu Komputer dan Informasi (Journal of Computer Science and Information). 10/1 (2017), 11-18 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21609/jiki.v10i1.372 THE APPLICATION OF GRAPHOLOGY AND ENNEAGRAM TECHNIQUES IN DETERMINING PERSONALITY TYPE BASED ON HANDWRITING FEATURES Dian Pratiwi, Gatot Budi Santoso, Fiqih Hana Saputri Trisakti University, Jl. Kyai Tapa No.1 Jakarta Barat, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This research was conducted with the aim of developing previous studies that have successfully applied the science of graphology to analyze digital handwriting and characteristics of his personality through shape based feature extraction, which in the present study will be applied one method of psychological tests commonly used by psychologists to recognize human’s personality that is Enneagram. The Enneagram method in principle will classify the personality traits of a person into nine types through a series of questions, which then calculated the amount of the overall weight of the answer. Thickness is what will provide direction personality type, which will then be matched with the personality type of the result of the graphology analysis of the handwriting. Personality type of handwritten analysis results is processed based on the personality traits that are the result of the identification of a combination of four dominant form of handwriting through the software output of previous studies, that Slant (tilt writing), Size (font size), Baseline, and Breaks (respite each word). From the results of this research can be found there is a correlation between personality analysis based on the psychology science to the graphology science, which results matching personality types by 81.6% of 49 respondents data who successfully tested. -

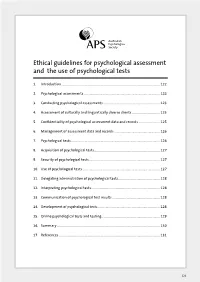

Ethical Guidelines for Psychological Assessment and the Use Of

Ethical guidelines for psychological assessment and the use of psychological tests 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 122 2. Psychological assessments .......................................................................................... 122 3. Conducting psychological assessments ................................................................... 123 4. Assessment of culturally and linguistically diverse clients ................................. 125 5. Confidentiality of psychological assessment data and records ......................... 125 6. Management of assessment data and records ...................................................... 126 7. Psychological tests ......................................................................................................... 126 8. Acquisition of psychological tests .............................................................................. 127 9. Security of psychological tests .................................................................................... 127 10. Use of psychological tests ............................................................................................ 127 11. Delegating administration of psychological tests ................................................. 128 12. Interpreting psychological tests ................................................................................. 128 13. Communication of psychological test results ....................................................... -

List of Neuropsychological and Psychological Tests.Xlsx

List of Neuropsychological and Psychological Tests *includes administration, scoring, interpretation and report writing* Instrument Type Age Minutes* Comments Achenbach system of Empirically Based Assessment Behavior Rating Scale 1.5‐18 60 May not be covered as stand‐alone measure ACTeERS‐ADD‐H Comprehensive, Teacher rating scale Behavior Rating Scale 3‐18 15 May not be covered as it is rating scale for ADHD Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS II) Behavior Rating Scale 0‐89 30 Adaptive Behavior Scale (ABS) Developmental 3‐18 30 ADHD Rating Scale ADHD 4‐18 15 ADHD Adolescent Anger Rating Scale Behavior Rating Scale 11‐19 15 Adolescent Apperception Cards Projective Personality 12‐19 60 Admin. Time 20 min. + 10 min. for scoring, Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL) Behavior Rating Scale 18‐89 30 interpretation, write up Adolescent Psychopathology Scale Personality child‐adult 60 Alzheimer's Quick Test (AQT) Neuropsychological Adult 10 Primarily neuropsychological testing Amen System Checklist Behavior Rating Scale Adult 15 Animal Naming Neuropsychological child‐adult 10 Primarily neuropsychological testing Aphasia Screening Test (Reiten Indiana) Neuropsychological 5+ 30 Primarily neuropsychological testing Asperger's Syndrome Diagnostic Scales (ASDS) ASD Rating Scale 5‐18 20 Attention Deficit Disorder Eval. Scales (ADDES) Behavior Rating Scale 5‐18 15 ADHD Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Test (ADHDT) Behavior Rating Scale 3‐23 10 ADHD Attention Deficit Scales for Adults Behavior Rating Scale 17+ 15 ADHD Auditory Consonant Trigram