Producing, Branding and Managing Multifaceted Tourist Destinations: Cartagena, Colombia, As a Study Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article (Published Version)

Article Tourism challenges facing peacebuilding in colombia NAEF, Patrick James, GUILLAND, Marie-Laure Abstract Declaring that a tourist Colombia guarantees a post-conflict reconstruction is not a performative act. We must therefore ask ourselves whether perceiving tourism as a tool in the service of peace is more of a myth or a reality. After a brief look at the recovery of Colombian tourism since the beginning of the 2000s, this article aims to observe some of the challenges that have characterised the sector since the signing of peace agreements between the government and the FARC-Ep, such as the rebuilding the country's image, prostitution and narco-tourism, the issue of access to land and resources, the promotion of eco-tourism and "community" tourism, and the role of this industry in the reintegration of demobilised combatants. Reference NAEF, Patrick James, GUILLAND, Marie-Laure. Tourism challenges facing peacebuilding in colombia. Via Tourism Review, 2019, vol. 15 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:129730 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Via Tourism Review 15 | 2019 Tourisme et paix, une alliance incertaine en Colombie Tourism challenges facing peacebuilding in Colombia Marie-Laure Guilland and Patrick Naef Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/viatourism/4046 ISSN: 2259-924X Publisher Association Via@ Electronic reference Marie-Laure Guilland and Patrick Naef, « Tourism challenges facing peacebuilding in Colombia », Via [Online], 15 | 2019, Online since 22 November 2019, connection on 24 December 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/viatourism/4046 This text was automatically generated on 24 December 2019. -

1 Review on Tourism Activity in Colombia Authors

Review on tourism activity in Colombia Authors/Collaborators: ProColombia- Vice Presidency of Tourism 1. MAIN FINDINGS 1.1. Colombia has been improving its tourism performance From 2012 to 2019, the receptive tourism grew in an average annual growing of 9,1% in comparison to the world growth 5,3% and America’s growth 4,4%. In 2019, international arrivals increased 3,9% compared to 2018 thanks to the arrival of 104.982 travelers to the country. The increasing arrival of non-resident visitors to Colombia has allowed tourism to be the second generator of foreign exchange for the country, only surpassed by the mining-energy sector. According to Colombia’s National Bank (Banco de la República), tourism was the second generator of foreign exchange in 2019, surpassing the incomes generated by traditional products such as coffee, flowers, and bananas. In 2019, the tourism sector generated 6,751 million dollars, an amount 2% higher than that registered in 2018. In 2018, tourism generated 1,974,185 jobs. The category that generated the most employment was transportation with 38.7% and restaurants with 35.8%. 1.2. Colombia’s image and brand reputation enhancement Colombia has been working on its image and reputation to be recognized for its cultural and natural diversity. As a result of this effort, in 2019 the United States Tour Operators Association recognized and recommended Colombia as a “Top Hot Destination” for 2020. Also, in 2019 Colombia was recognized as the leading destination in South America by the World Travel Awards. Not only the tourism industry is talking about Colombia, important media such as The New York Times, Condé Nast Traveler and Lonely Planet, among others, have included Colombia as a must-visit destination. -

Nature Tourism on the Colombian—Ecuadorian Amazonian Border: History, Current Situation, and Challenges

sustainability Article Nature Tourism on the Colombian—Ecuadorian Amazonian Border: History, Current Situation, and Challenges Carlos Mestanza-Ramón 1,2,3,* and José Luis Jiménez-Caballero 1 1 Departamento Economía Financiera y Dirección de Operaciones, Universidad de Sevilla, 41018 Sevilla, Spain; [email protected] 2 Instituto Superior Tecnológico Universitario Oriente, La Joya de los Sachas 220101, Ecuador 3 Research Group YASUNI-SDC, Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo, Sede Orellana, El Coca EC 220001, Ecuador * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Global conflicts can severely affect a nation’s tourism activities. Tourism can also be seriously affected by health problems such as epidemics or pandemics. It is important to establish strategies to be prepared for adverse situations. The objective of this study focused on analyzing nature tourism from a post-conflict and post-COVID-19 situation in the Amazonian border of Colombia (Department of Putumayo) and Ecuador (Province of Sucumbíos), which will contribute to establishing future strategic management scenarios. In order to respond to this objective, a systematic bibliographic review was carried out, accompanied by fieldwork (interviews). The results indicate that in the face of adverse situations, the tourism industry has the capacity to be resilient. The success of its recovery will be directly proportional to its capacity to create policies and strategies that allow it to take advantage of natural resources and turn them into an opportunity for the socioeconomic development of its population. Citation: Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Jiménez-Caballero, J.L. Nature Keywords: post-conflict; post-pandemic; Sucumbíos; Putumayo; resilience; COVID-19; sustain- Tourism on the able tourism Colombian—Ecuadorian Amazonian Border: History, Current Situation, and Challenges. -

COLOMBIA – U.S. INVESTMENT ROADMAP Index

COLOMBIA – U.S. INVESTMENT ROADMAP Index Foreword by Flavia Santoro: Outlines the existing synergies in the U.S. and Colombian markets, highlighting Colombia as a business ally. Introduction by José Manuel Restrepo Abondano: Discusses how to deepen investment and trade in traditional sectors, with a focus on improving the investment climate in both countries through regulatory coherences, trade facilitation, and full application of the Free Trade Agreement. Letter from the Project Partners by Myron Brilliant and Bruce Mac Master: Highlights the value of the Colombia-U.S. Trade and Investment Roadmap and the importance of the bilateral commercial ties. • Executive Summary • Colombia and the United States: Two Countries With Long-Standing Relations • New opportunities to explore • Colombia’s Economic Beliefs • The Team • Success Stories • FAQs and Investor Resources Our aim at ProColombia, the country’s country is home to more than 32 Investment, exports, and tourism million hectares available to grow Colombia: promotion body is to incentivize and fruit, vegetables, cacao, coffee, and boost more American investment in tea, among other products. Our rich Colombia, as much in the stock market biodiversity also presents innovative A Key Destination as in the diverse productive sectors opportunities in the cosmetics, chemicals in which we have important trade and life sciences sectors. for Investment opportunities. Tourism continues to grow every year, By: Flavia Santoro We want to encourage the inflow of not just in the number of visitors but also President of ProColombia resources to undertake lucrative projects in range of possibilities for the hospitality in the public and private sectors across services industry, this is in large part here has rarely been a better time to our country in the past 15 years. -

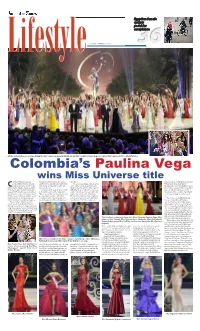

P40 Layout 1

Egyptian female cyclists pedal for acceptance TUESDAY, JANUARY 27, 2015 36 All the contestants pose on stage during the Miss Universe pageant in Miami. (Inset) Miss Colombia Paulina Vega is crowned Miss Universe 2014.— AP/AFP photos Colombia’s Paulina Vega wins Miss Universe title olombia’s Paulina Vega was Venezuelan Gabriela Isler. She edged the map. Cuban soap opera star William Levy and crowned Miss Universe Sunday, out first runner-up, Nia Sanchez from the “We are persevering people, despite Philippine boxing great Manny Cbeating out contenders from the United States, hugging her as the win all the obstacles, we keep fighting for Pacquiao. The event is actually the 2014 United States, Ukraine, Jamaica and The was announced. what we want to achieve. After years of Miss Universe pageant. The competition Netherlands at the world’s top beauty London-born Vega dedicated her title difficulty, we are leading in several areas was scheduled to take place between pageant in Florida. The 22-year-old mod- to Colombia and to all her supporters. on the world stage,” she said earlier dur- the Golden Globes and the Super Bowl el and business student triumphed over “We are proud, this is a triumph, not only ing the question round. Colombian to try to get a bigger television audi- 87 other women from around the world, personal, but for all those 47 million President Juan Manuel Santos applaud- ence. and is only the second beauty queen Colombians who were dreaming with ed her, praising the brown-haired beau- The contest, owned by billionaire from Colombia to take home the prize. -

El Ballet De Colombia

Señorita Antioquia® Señorita Arauca® Señorita Atlántico® Señorita Bogotá D.C.® Olivia Aristizábal Echeverry Valentina Díaz Mantilla Daniella Margarita Álvarez Melissa Cano Rey Señorita Bolívar® Señorita Boyacá® Señorita Caldas® Señorita Caquetá® Señorita Cartagena D.T. y C.® Rossana Fortich González Lina María Gallego Bejarano Valentina Muñoz Escobar Lizeth Mendieta Villanueva Laura Marcela Cantillo T . Señorita Cauca® Señorita Cesar® Señorita Chocó® Señorita Cundinamarca® Señorita Guajira® Jenniffer Martínez Martínez María Laura Quintero D. Yesica Paola Montoya V. Thael Osorio Redondo Vanessa Carolina Chóles V. www.srtacolombia.org Presidente Raimundo Angulo Pizarro Directora Ejecutiva Rosana Vanegas Pérez Señorita Huila® Señorita Magdalena® Señorita Meta® Asesor de Presidencia Daniella Villaveces Díaz Melissa Carolina Varón B. Sara Daniela Villarreal P. Diego Guarnizo Monroy JUNTA DIRECTIVA MIEMBROS INSTITUCIONALES Judith Pinedo Flórez Alcaldesa Mayor de Cartagena de Indias, D. T. y C. Contralmirante Cesar Augusto Narváez Arciniegas Comandante Fuerza Naval del Caribe Antonio Quinto Guerra Varela H. Concejal de Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C. MIEMBROS NO INSTITUCIONALES PRINCIPALES Raimundo Angulo Pizarro Señorita Nariño® Señorita Norte de Santander® Señorita Quindío® Presidente Catalina Lasso Ortiz Mayra Alejandra Osorio Ch. Estefanía Diaz Granados G Nicolás Pareja Bermúdez Secretario . Lupe Yidios de Lemus Elizabeth Noero de Lemaitre Antonio Lozano Pareja Jaime Méndez Galindo SUPLENTES Socorro Covo de Rodríguez Astrid Herrera Téllez -

Systematic Competitiveness in Colombian Medical Tourism:Systematic an Competitiveness Examination in Colombian Medical Tourism: an Examination

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.70135 Provisional chapter Chapter 8 Systematic Competitiveness in Colombian Medical SystematicTourism: An Competitiveness Examination in Colombian Medical Tourism: An Examination Mario Alberto De la Puente Pacheco Mario Alberto De la Puente Pacheco Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70135 Abstract This chapter analyzes the role of the central government of Colombia in the strategy for the improvement of the medical tourism industry through a critical approach of the traditional model of competitiveness. Based on a mixed method, the feasibility of the associative systemic competitiveness model and its effectiveness on the quality of medi‐ cal services offered to foreign patients is determined. Under the current competitive‐ ness model, the central government implements a series of strategies based on executive orders in an isolated way. The proposal for the implementation of systemic competitive‐ ness model improves the perception of quality of medical services by foreign patients. In order to implement the proposed model, it recommended the expansion of free taxation zones, the proliferation of medical service clusters, and the strengthening of strategic alli‐ ances with international operators. Keywords: systemic competitiveness, medical tourism, government role, traditional competitiveness model, health tourism 1. Introduction The international medical tourism is the voluntary mobility of patients to foreign countries searching affordable and high‐quality treatments. The growing need to meet the demand for medical procedures outside the country of origin due to local market failures has increased the international mobility, through agreements between insurance companies and the travel of particular patients who seek healthcare procedures in many cases without knowing the legal and physical risks. -

P Mainstreaming Biodiversity Conservation in the Tourism

GEF-7 PROJECT IDENTIFICATION FORM (PIF) PROJECT TYPE: FULL SIZE PROJECT TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEF TRUST FUND PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Mainstreaming biodiversity conservation in the tourism sector of the protected areas and strategic ecosystems of San Andres, Old Providence and Santa Catalina islands Country(ies): Colombia GEF Project ID: GEF Agency(ies): WWF GEF GEF Agency Project ID: Project Executing Corporation for the Submission Date: Entity(s): Sustainable Development of the Archipelago of San Andrés, Old Providence and Santa Catalina (CORALINA); and Conservation International Foundation (CI). GEF Focal Area(s): Biodiversity Project Duration 42 (Months) A. INDICATIVE FOCAL/NON-FOCAL AREA ELEMENTS (in $) Trust Fund Programming Directions Co-financing GEF Project Financing BD 1.1 GEFTF 1,522,500 17,083,463 BD 2.7 GEFTF 1,129,794 2,116,079 Total Project Cost 2,652,294 19,199,542 1 B. INDICATIVE PROJECT DESCRIPTION SUMMARY Project Objective: To promote biodiversity conservation mainstreaming in the tourism sector of the Protected Areas and strategic ecosystems of San Andres, Old Providence and Santa Catalina islands through the design and implementation of participatory governance models, effective policies and biodiversity friendly tourism products. Project Compo Project Project (in USD$) Components nent Outcomes Outputs Type GEF Project Co-financing Financing Component TA Outcome 1.1: Output 1.1.1: 810,000 15,850,000 1: Planning Biodiversity Interinstitutional and is coordination Institutional mainstreame group created Framework d into tourism to advise and for a for MPA, PAs accompany the biodiversity and three design and focused islands of the implementation tourism sector Archipelago, of a new in the MPA, for improved sustainable PAs and three protection of tourism plan for islands of the corals, sandy MPA, PAs and Archipelago, beaches, the three in the context mangroves islands, in the of the and key context of POMIUAC. -

Bruins Go up on Whalers Person on Her Street

y A Panned Squared Abortion A Industrial-to-residential Whalers win in OT Debate shifts change rejected/3 to even up NHL series/11 to state House/4 mianrhpBlpr lUpralh Monday, April 16,1990 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm Newsstand Price: 35 Cents /v-ii iUaurbpfitrr Hrralb starling says money Bus evades is motivating force Lithuanians quick fix told: expect SPORTS see page 39 By Rick Santos Manchester Herald Terrie Dittmann, who lives at 236 Knollwood Road, was awakened at 6:45 this morning when a Connecticut ‘hectic’ week Transit bus roared past her home. Dittmann says she wouldn’t be so upset if the bus, which passes every the Supreme Council, Lithuania’s By Brian Friedman parliament weekday morning and afternoon, picked up at least one The Associated Press Bruins go up on Whalers person on her street. The full parliament is to meet Thesday. But it doesn’t. MOSCOW — Lithuania’s leader The only reason the bus travels on Knollwood, which Ozolas also said that Lithuania ship today discussed what to do and Estonia planned to exchange branches eastward off Vernon Street and loops back onto about a I^ m lin threat to cut off NHL Playoffs itself, is to turn around. ambassadors today, according to crucial supplies to the Baltic Aidas Palubinskas of the Lithuanian And a bus company official says the bus wouldn’t republic for ignoring a deadline to o even get near Dittmann’s home or Knollwood if it didn’t I^liament’s information office. BOSTON (AP) — Cam Neely’s shorthanded goal repeal laws that break with Moscow. -

Meetings Industry 09

ISSN No. 2711-4317 09. MEETINGS INDUSTRY 09. MEETINGS INDUSTRY Infrastructure, creativity, and hospitality at your service for future events future service for and hospitality at your creativity, Infrastructure, Colombia: a must-see destination a must-see Colombia: 09 09 TABLE OF CONTENTS — Page 04 — Behind the Scenes at a Large Convention MARY KAY SEMINAR 2020 — Page 10 — Infrastructure for Congresses and Conventions ISSUE 09 IDEAL VENUES FOR LARGE EVENTS — Page 16 — Meetings Tourism Weddings FOUR PHOTOGRAPHERS REVEAL COLOMBIA’S MOST ROMANTIC DESTINATIONS Colombia’s beaches, mountains, and rivers attract ara—are other event segments the country is strong travelers year-round, but that’s not its only draw. in. — Page 22 — Colombia can certainly fill the criteria for hosting Our commitment and standing as an exem- Excellence in large events as well, whether the objective be to con- plary meetings destination can be seen in Colom- duct work meetings, exchange knowledge, do busi- bia’s major cities, where proper infrastructure has Incentive Travel ness, or boost company productivity. been developed, state-of-the-art technology has Travel Solutions: Crystal Award According to data from the 2018 country-wide been adopted, and regionally competitive prices study on the Economic Contribution of Meetings have been set. In smaller municipalities, expertise Tourism, Colombia was the chosen destination for in customer service has transformed Colombia’s — Page 28 — nearly 68,000 congresses, conventions, and incen- history into unparalleled selling points for hosting Incentive Trips tive trips with a total of 5.2 million attendees. These unique events. As for our people, Colombia is proud UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES WITH YOUR TEAM events were held in hotels, convention centers, of its hard-working people willing to give their best and other venues, and brought with them nearly to ensure Colombia’s success. -

Septiembre a Diciembre De 2015 Pepe Medel

Septiembre a diciembre de 2015 History of Beauty Comentarios, anécdotas y relatos sobre los concursos de belleza. Tomo I Pepe Medel Septiembre a diciembre de 2015 Contenido general Presentación……………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 1 Septiembre……………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Octubre…………………………………………………………………………………………. 42 Noviembre……………………………………………………………………………………… 90 Diciembre………………………………………………………………………………………. 126 Presentación Muchos de los lectores de mi blog personal en Facebook History of Beauty (https://www.facebook.com/historiadelabelleza) me han solicitado que republique algunas de las notas que han considerado interesantes y que en su momento no pudieron leer y que además por el tiempo en que las publiqué, es muy difícil buscarlas en la página, a pesar de señalarles la fecha en que las subí a la red. Ante esta situación decidí re trabajar cada una de las notas y organizarlas a manera de un libro en línea que rescate todos esos comentarios y que los interesados lo puedan bajar de 2 la red, imprimir, coleccionar o lo que ustedes decidan. Esta colección que publicaré cuatrimestralmente se denomina: History of Beauty. Comentarios, anécdotas y relatos sobre los concursos de belleza. Es por esto que con mucho gusto les presento el primer tomo de este esfuerzo, el cual comprende las notas publicadas desde la aparición de mi blog el 9 de septiembre de 2015 y comprende hasta la última aportación subida en diciembre del mismo año. Esta publicación incluye las 185 fotografía empleadas en las diversas notas que escribí durante el último cuatrimestre del año 2015 y que en algunos casos, son fotografías que solicitaron subiera y yo aproveché para hacer un breve artículo. Espero que con la lectura de este tomo, los jóvenes aficionados a los concursos de belleza puedan encontrar los orígenes de nuestra pasión y los que ya son grandes conocedores del tema, logren revivir la emoción que nos siguen causando los certámenes que, al menos a mí, se han convertido en parte de mi vida y han convivido conmigo por más de 50 años. -

Territorial Tourists FINAL

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Tourists and Territory: Birders and the Prosaic Geographies of Stateness in Post-conflict Colombia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3ws7v3c5 Author Bott, Travis Aaron Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Tourists and Territory: Birders and the Prosaic Geographies of Stateness in Post-conflict Colombia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the degree Master of Arts in Geography by Travis Bott 2019 ã Copyright by Travis Bott 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Tourists and Territory: Birders and the Prosaic Geographies of Stateness in Post-conflict Colombia By Travis Bott Master of Arts in Geography University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor John Agnew, Chair This paper probes the role of birders as agents of re-territorialization in post-conflict Colombia. The 2016 signing of the peace accord between the Colombian government and the FARC ended the longest-running civil conflict in the western hemisphere, and marked the beginning of the state’s territorial re-integration project. An unlikely group has been in the initial wave of this territorial re-taking: birders. Due to Colombia’s position as a hotbed of avian biodiversity, the relative inaccessibility to large swathes of its territory, and the unique drive to add species to their personal lists, birders have been aggressive first-responders to this territorial re-opening. While questions of re-territorialization often conjure Weberian images of the state, this paper explores the line between the state as the fundamental actor in re-territorialization and the non- state actors that do the work of territorialization for the state.