The Work of Authorship a the Work of Authorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accommodation

Accommodation Algarve Albufeira São Rafael Suite Hotel Hotel accommodation / Hotel / ***** Address: Caminho das Sesmarias8200-613 Sesmarias, AlbufeiraAlgarve, Portugal Telephone: +351 289 540 300 Fax: +351 289 540 314 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.saorafaelsuites.com/ Almancil Aldeamento Turístico Martinhal Quinta Monte da Quinta Resort Tourist Villages / **** Hotel accommodation / Aparthotel / ***** Address: Quinta do Lago 8135-162 Almancil Address: Avenida André Jordan, Apartado 2147Quinta do Telephone: +351 289 000 300 Fax: +351 289 000 301 Lago - 8135-998 Almancil Telephone: +351 289 000 300 Fax: +351 289 000 305 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.martinhal.com E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.montedaquintaresort.com/ Lagos CAMPING TURISCAMPO bungalow park Camping / Private Address: Estrada Nacional 125, Espiche8600-109 Lagos Telephone: +351 282 789 265 Fax: +351 282 788 578 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.turiscampo.com Portimão Hotel Le Meridien Penina Golf & Resort Hotel accommodation / Hotel / ***** Address: Po Box 146, Penina8501-952 Portimão Telephone: +351 282 420 200 Fax: +351 282 420 300 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.penina.com 2013 Turismo de Portugal. All rights reserved. 1/45 [email protected] Quarteira Aquashow Park Hotel Hotel accommodation / Hotel / **** Address: Semino, E.N. 396 8125-303 Quarteira Telephone: +351 289 317 550 Fax: +351 289 317 559 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.aquashowparkhotel.com -

Jörg Böckem Und Christoph Dallach Fotos: Heidi Nikolaisen

TEXT: JÖRG BÖCKEM UND CHRISTOPH DALLACH FOTOS: HEIDI NIKOLAISEN Melodie und Melancholie: Anne Lilia Berge Strand, Sondre Lerche, Erlend Øye und Eirik Glambek Bøe, Mikal Telle s ist noch nicht allzu lange her, war das Einzige, was den Leuten in 100 000 Alben verkaufen, gelten die da galt ein norwegischer Musi- London zu unserer Heimat einfiel.“ Norweger als Hoffnung der modernen Eker, der auf die verwegene Idee Seitdem hat sich ein Menge geändert. Popmusik. verfiel, bei einer englischen Platten- Talentscouts der Plattenfirmen pilgern Der Ursprung des ganzen Wirbels ist firma wegen eines Vertrags vorzuspre- seit vergangenem Jahr in Scharen in die kleine Hafenstadt Bergen, 60 Grad chen, automatisch als Witzfigur: die Heimat von a-ha und versuchen, 23 Minuten nördlicher Breite. So wie ãEgal, wo wir hinkamen, es war immer mit hoch dotierten Verträgen bewaff- in den letzten Jahrzehnten in Man- dasselbe“, erinnert sich Pål Waaktaar- net, auch einen Norweger für ihr chester, Seattle oder jüngst Paris ist Savoy, Gitarrist der norwegischen Pop- Unternehmen einzufangen. Seit junge hier eine Szene entstanden, deren Mu- Pioniere „a-ha“, an die Anfangstage norwegische Bands wie Röyksopp und sik das Potenzial hat, Norwegen nun seiner Karriere. „‚Ach, ihr seid aus Kings of Convenience mit ihren Alben zum Mittelpunkt der europäischen Norwegen? Wie lustig! Das ist doch nicht nur in Norwegen die Spitze der Popwelt zu erheben. das Land, das beim Grand Prix d’Eu- Charts erreichten, sondern auch Kri- Bergen ist mit 229 000 Einwohnern rovision null Punkte geholt hat!‘ Das tiker weltweit begeistern und rund die zweitgrößte Stadt Norwegens. Der Schlechtwetter- stimmung am Nordmeer: Party in einer ehemaligen Sardinenfabrik im Industriehafen Stadtkern, inmitten von Wohn- und sestadt schon von jeher zu den wohlha- treffen sie sich privat mit ihren Freun- Industriegebieten, sieht aus, als hätte bendsten Orten. -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

Bergen Kommune Brosjyre.ENG.Indd

The City is Bergen History • Nature • Industry • Culture Street life • Services City of Water FACTS ABOUT BERGEN With a population of 240.000, Bergen is Norway’s second largest As the capital of Western city and the largest in the county of Hordaland. It is also the capital Norway, Bergen has devel- of Western Norway, which is the leading region for all signifi cant oped close ties with other municipalities in the region, Norwegian export industries. such as joint ownership of the Port Authorities of Bergen is a charming blend of tradition and innovation. Throughout Bergen, the regional waste history Bergen has built a strong reputation as a centre for trade and management company BIR shipping. This is due to its strategic location on the coast. Proximity and the regionally owned power company BKK. to the sea has continued to provide benefi ts for the maritime and marine industries and for tourism. The Bergen region has the most complete maritime environment and is also an international centre of infl uence for fi sheries, aquaculture and seafood. Western Norway produces 80% of Norway’s exports of crude oil, and the Bergen region is home to a leading expertise within oil and gas on a global scale. Bergen has a considerable shipping fl eet, and the city is dominant in the global market of transporting chemicals and other goods. The Bergen region is also home to strong and growing industries within information and communication technology (ICT), media, the arts and education. The municipality supports several network organisations, such as Maritime Bergen, Fiskeriforum Vest, Bergen Tourist Board, Hordaland Oil and Gas, Education in Bergen and Bergen Media City. -

NINA KATCHADOURIAN Born 1968 in Stanford, CA Lives and Works in Brooklyn, NY [email protected]

NINA KATCHADOURIAN Born 1968 in Stanford, CA Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY [email protected] www.ninakatchadourian.com EDUCATION 1996 Whitney Museum Independent Study Program 1993 University of California, San Diego M.F.A., Visual Art 1989 Brown University B.A. Visual Arts and B.A. Literature and Society (Honors) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Solo traveling exhibition curated by Veronica Roberts, the Blanton Museum, Austin, TX (catalog) 2015 Kansas Cut-Up, Kentucky Museum of Arts and Crafts, Louisville Sorted Books, Byrdcliffe Guild, Woodstock, NY 2014 Nina Katchadourian: Seat Assignment, Gund Gallery at Kenyon College Seat Assignment, Cecilia Brunson Projects + Basha Projects, London 2013 Two Libraries: Recently Sorted Books, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco Return Trip, testsite, Austin, TX Grand State of Maine, permanent public commission for GSA, Van Buren, ME 2012 Seat Assignment, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco Once Upon a Time in Delaware/In Quest of the Perfect Book, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE 2011 Seat Assignment, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Dunedin, New Zealand 2010 Sorted Books, Clifford Art Gallery, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY Sorted Books, Philip Feldman Gallery at Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR 2009 Nina Katchadourian, Galeria Llucia Homs, Barcelona, Spain Tech Tools of the Trade, Contemporary New Media Art, de Saisset Museum at Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA 2008 A Fugitive, Some Maps, Cute Animals and a Shark, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, CA Nina Katchadourian: -

Kings of Convenience

1 Kings of CONVENIENCEPor: Cecilia González Michalak Kings of Conve- las guitarras acústi- otras clásicas como nience es un dúo de cas, añadiendo oca- Simon & Garfunkel. Indie pop - Folk Pop sionalmente arreglos También se pueden formado por Erlend de cuerda o piano, y distinguir en sus no- Øye y Eirik Glambek recibe una gran in- tas algunas pincel- Bøe, procedente de fluencia de bandas adas de Bossa Nova 8 Bergen, Noruega. Su actuales como Belle en la sonoridad de música se basa en & Sebastian y de sus guitarras. F o t o : G o o g l e I m a g e s 2 Kings of Convenience Eirik Glambek Boe Nació el 25 de Octu- tadas de los discos de del mismo año real- visitaron México para bre de 1975 en Ber- Kinas of Convenience. izaron el album re- dar su primer conci- gen, Noruega. Estudió mix llamado Versus. erto en Latinoamérica. psicología en la Uni- En 1990 formó con Er- El single Toxic Girl le versidad de Bergen, lend Øye una banda trajo a la música de En 2006 colaboró con aunque su pasión llamada Skog, pero se Glambek la atención de su dupla en el proyecto siempre fue la música. transformó en la banda numerosos fans y re- paralelo de Erlend, The actual en 1998 cuando cibió buena crítica so- Whitest Boy Alive, para Aunque su lenguaje prepararon la produc- bre la simplicidad y cali- abrir con su propia natal es el noruego, ción de su primer al- dad lírica de la canción. banda Kommode, que muchos de sus escri- bum, al cuál le siguió están actualmente gra- tos han sido en inglés, Quiet is the New Loud En 2004, Kings of Con- bando su primer albúm destacando sus com- en enero del 2001. -

Declaration of Dependence Kings of Convenience Rar

Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar 1 / 4 Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar 2 / 4 3 / 4 Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience Rar >>> http://bltlly.com/14kkih.. Shop for Vinyl, CDs and more from Kings Of Convenience at the Discogs Marketplace. ... Kings of Convenience are an indie folk-pop duo from Bergen, Norway. ... ASW 06840, Kings Of Convenience - Declaration Of Dependence album art .... Plik Kings Of Convenience 2009 Declaration Of Dependence.rar na koncie użytkownika SumaWszystkichLudzi • folder 2009-Declaration Of Dependence • Data .... Download: «Declaration of Dependence» – Kings of Convenience. Descargas, Radio. Muchos de ustedes han compartido a través de sus comentarios la .... Riot On An Empty Street Kings Of Convenience Rar ... Cayman Islands Riot On An Empty Street 3:02 1.29 4 Freedom And Its Owner Declaration Of Dependence .... 38bdf500dc Kings Of Convenience-Declaration Of Dependence Full Album Zip >> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1) e31cf57bcd Cerita Hantu Malaysia .... “Failure” (aransemen oleh Kings of Convenience) – 4:56 11. “Leaning Against the ... Declaration of Dependence (2009). 1. “24-25” 3:38 2.. Kings Of Convenience - Me in You (Letras y canción para escuchar) - Crossroads and given the option ... Declaration Of Dependence Kings Of Convenience.. 2009 release, the third album from the Norwegian Pop/Folk duo (Erik Boe and Erlend Oye). Declaration of Dependence is the story of two people living two very .... Declaration of Dependence is the third album from Norwegian duo Kings of Convenience, their first album in five years. It was released on October 5, 2009.. Kings of Convenience son un dúo de Indie pop - Folk Pop formado por Erlend Øye y Eirik Glambek Bøe y .. -

Got Me Wrong

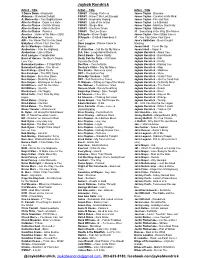

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D. -

LEIF Captures Essence of Scandinavian Melancholy in New Video

LEIF captures essence of scandinavian melancholy in new video “Scandinavian melancholy is the yearning for something you never had, the longing for that which never happened” . - LEIF With New Beat LEIF paints a quintessential picture of Scandinavian melancholy; those long, bright summer nights full of hope, which end up with you going home alone, again. The video is a vivid story of friendship, attraction and longing set in an archetypal Oslo nightscape. Two young guys have an instant connection and everything looks set for a perfect summer evening, right up until the girlfriend of one of them shows up unexpectedly. - Everyone has gone home alone through the city one light summer night and felt that unmistakable sense of longing. We pine for someone, something. It’s that nagging ache amongst all the beauty of life and living. Sometimes we get what we want...but most often we don’t. Watch the video for New Beat here Hailing from Bergen, on the rainy west coast of Norway (home of luminaries like Röyksopp, Kings of Convenience, Datarock and Aurora) LEIF had his breakthrough in 2011 making the final of the Urørt competition and radio-listing on NRK P3 as the front figure of the band Leif & The Future. The debut album Songs of Youth was extremely well received, with 5/6 in Dagbladet. Now he’s ready with his eagerly awaited debut solo album - Scandinavian Melancholy. - I’ve explored themes such as feelings of longing, a conservative Christian background, intimacy and bisexuality - in a Scandinavian context. I had a good upbringing, but much of my own melancholy derives from feelings of loss, things I never got to experience. -

Artist Title Count ATB FT. TOPIC & A7S YOUR LOVE 102 KID LAROI

Artist Title Count ATB FT. TOPIC & A7S YOUR LOVE 102 KID LAROI WITHOUT YOU 96 ROBIN SCHULZ FT. KIDDO ALL WE GOT 95 JASON DERULO FT. NUKA LOVE NOT WAR 91 OFENBACH & QUARTERHEAD HEAD SHOULDERS KNEES & TOES 90 PURPLE DISCO MACHINE & SOPHIE AND THEHYPNOTIZED GIANTS 86 OLIVIA RODRIGO DRIVERS LICENSE 82 AVA MAX MY HEAD & MY HEART 81 THE WEEKND SAVE YOUR TEARS 77 JOEL CORRY FT. RAYE & DAVID GUETTA BED 75 MILEY CYRUS FT. DUA LIPA PRISONER 73 TIESTO THE BUSINESS 73 TWOCOLORS LOVEFOOL 67 CLEAN BANDIT & MABEL TICK TOCK 61 JC STEWART I NEED YOU TO HATE ME 60 SIGALA & JAMES ARTHUR LASTING LOVER 59 MEDUZA FT. DERMOT KENNEDY PARADISE 58 TATE MCRAE YOU BROKE ME FIRST [LUCA SCHREINER REMIX]58 SHANE CODD GET OUT MY HEAD 57 JUSTIN BIEBER ANYONE 56 SAM SMITH DIAMONDS 55 DERMOT KENNEDY GIANTS 54 RUDIMENTAL FT. RAYE REGARDLESS 54 ALLE FARBEN & FOOL'S GARDEN LEMON TREE 53 SHAWN MENDES WONDER 53 TOM GREGORY RATHER BE YOU 53 JOEL CORRY FT. MNEK HEAD AND HEART 52 HARRY STYLES GOLDEN 51 TAYLOR SWIFT WILLOW 51 DUA LIPA WE'RE GOOD 50 ED SHEERAN AFTERGLOW 50 KYGO & DONNA SUMMER HOT STUFF 49 MICHAEL PATRICK KELLY BEAUTIFUL MADNESS 49 MALUMA & THE WEEKND HAWAI 49 MILEY CYRUS MIDNIGHT SKY 49 RITON X NIGHTCRAWLERS FRIDAY 49 RAG'N'BONE MAN ALL YOU EVER WANTED 47 BTS DYNAMITE 45 REGARD FT. RAYE SECRETS 45 ROBIN SCHULZ FT. FELIX JAEHN & ALIDA ONE MORE TIME 44 PURPLE DISCO MACHINE FEAT. MOSS KENA &FIREWORKS THE KNOCKS 43 DAVID PUENTEZ SUPERSTAR 42 JASON DERULO TAKE YOU DANCING 42 NATHAN EVANS WELLERMAN (220 KID X BILLEN TED RMX) 41 J BALVIN, DUA LIPA & BAD BUNNY UN DIA (ONE DAY) 40 LADY GAGA & ARIANA GRANDE RAIN ON ME 40 ZOE WEES GIRLS LIKE US 38 DIODATO FAI RUMORE 37 JUBEL & NEIMY DANCING IN THE MOONLIGHT 37 THE WEEKND BLINDING LIGHTS 37 TOPIC FEAT. -

Master Song List

Song Title Artist Dancing Queen ABBA Grow Old With You Adam Sandler Hello Adele Don't Matter Akon Freedom Akon Lonely (Mr. Lonely) Akon We're in This Love Together Al Jarreau It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alan Jackson Too Close Alex Clare Orange Sky Alexi Murdoch Not Even The King Alicia Keys I Need A Dollar Aloe Blacc Wake Me Up Aloe Blacc Left Hand Free Alt-J Breezeblocks Alt-J Something Good Alt-J Arms of a Woman Amos Lee Sweet Pea Amos Lee Chill In The Air Amos Lee Colors Amos Lee Keep It Loose Keep It Tight Amos Lee Supply and Demand Amos Lee What's Been Going On Amos Lee Mx Missiles Andrew Bird Keep Your Head Up Andy Grammar Angry Anymore Ani DiFranco I and Love and You Avett Brothers Head full of Doubt/Road Full of Promise Avett Brothers Murder In The City Avett Brothers Shame Avett Brothers Swept Away Avett Brothers Weight of Lies Avett Brothers The Weight Band Call and Answer Barenaked Ladies If I Had A Million Dollars Barenaked Ladies When I Fall Barenaked Ladies All I Want Is You Barry Louis Polisar Pompeii Bastille God Only Knows Beach Boys All You Need Is Love Beatles Blackbird Beatles Here Comes The Sun Beatles 1 Song Title Artist Hey Jude Beatles In My Life Beatles Let It Be Beatles Real Love Beatles Yesterday Beatles Across The Universe Beatles All My Loving Beatles Eleanor Rigby Beatles For No One Beatles I Will Beatles I've Just Seen A Face Beatles Rocky Racoon Beatles With A Little Help From My Friends Beatles Loser Beck Get Me Away From Here, I'm Dying Belle And Sebastian Judy And The Dream Of Horses Belle And Sebastian -

The Ultimate Playlist This List Comprises More Than 3000 Songs (Song Titles), Which Have Been Released Between 1931 and 2018, Ei

The Ultimate Playlist This list comprises more than 3000 songs (song titles), which have been released between 1931 and 2021, either as a single or as a track of an album. However, one has to keep in mind that more than 300000 songs have been listed in music charts worldwide since the beginning of the 20th century [web: http://tsort.info/music/charts.htm]. Therefore, the present selection of songs is obviously solely a small and subjective cross-section of the most successful songs in the history of modern music. Band / Musician Song Title Released A Flock of Seagulls I ran 1982 Wishing 1983 Aaliyah Are you that somebody 1998 Back and forth 1994 More than a woman 2001 One in a million 1996 Rock the boat 2001 Try again 2000 ABBA Chiquitita 1979 Dancing queen 1976 Does your mother know? 1979 Eagle 1978 Fernando 1976 Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! 1979 Honey, honey 1974 Knowing me knowing you 1977 Lay all your love on me 1980 Mamma mia 1975 Money, money, money 1976 People need love 1973 Ring ring 1973 S.O.S. 1975 Super trouper 1980 Take a chance on me 1977 Thank you for the music 1983 The winner takes it all 1980 Voulez-Vous 1979 Waterloo 1974 ABC The look of love 1980 AC/DC Baby please don’t go 1975 Back in black 1980 Down payment blues 1978 Hells bells 1980 Highway to hell 1979 It’s a long way to the top 1975 Jail break 1976 Let me put my love into you 1980 Let there be rock 1977 Live wire 1975 Love hungry man 1979 Night prowler 1979 Ride on 1976 Rock’n roll damnation 1978 Author: Thomas Jüstel -1- Rock’n roll train 2008 Rock or bust 2014 Sin city 1978 Soul stripper 1974 Squealer 1976 T.N.T.