There's a Sudden Burst of Color in L.A.'S Improv Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 2 (2016)

TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES 2 (2016) ● Directed by Dave Green ● Distributed by Paramount Pictures ● 112 minutes ● PG13 ● 135 million dollar budget (180 with promotion) QUICK THOUGHTS ● Phil Svitek ● Demetri Panos DEVELOPMENT ● After the 2014 film exceeded box office expectations, Paramount and Nickelodeon officially announced a sequel was greenlit, and set to be released in theatres on June 3, 2016 ○ The sequel was announced two days after Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (2014) was released ● They planned to incorporate Bebop, Rocksteady and Casey Jones ● Jonathan Liebesman and Brad Fuller were also interested in doing a storyline that involved Dimension X and Krang ● In December 2014, it was revealed Paramount was in early negotiations with Earth to Echo director Dave Green to helm the sequel, also revealing Jonathan Liebesman was no longer a part of the project ● Known briefly as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Half Shell, Paramount revealed in December 2015 that the title had officially been changed to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows WRITING ● Josh Appelbaum and Andre Nemec, the writers of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows, have inked a twoyear, firstlook feature deal with Paramount Pictures ○ The duo have become goto scribes for the studio, having worked on the Paramount franchise pic Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol, which earned nearly $700 million worldwide, and the initial Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles reboot, which grossed almost $500 million. They also are -

Bridesmaids”: a Modern Response to Patriarchy

“Bridesmaids”: A Modern Response to Patriarchy A Senior Project presented to The Faculty of the Communication Studies Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Blair Buckley © 2013 Blair Buckley Buckley 2 Table of Contents Introduction......................................................................................... 3 Bridesmaids : The Film....................................................................... 6 Rhetorical Methods............................................................................. 9 Critiquing the Artifact....................................................................... 14 Findings and Implications................................................................. 19 Areas for Future Study...................................................................... 22 Works Cited...................................................................................... 24 Buckley 3 Bridesmaids : A Modern Response to Patriarchy Introduction We see implications of our patriarchal world stamped across our society, not only in our actions, but in the endless artifacts to which we are exposed on both a conscious and subconscious basis. One outlet which constantly both reflects and enables patriarchy is our media; the movie industry in particular plays a critical role in constructing gender roles and reflecting our cultural attitudes toward patriarchy. Film and sociology scholars Stacie Furia and Denise Beilby say, -

Shaun Boylan

Shaun Boylan Los Angeles, CA Height: 6”4’ | Weight: 215 lbs | Hair color: brown | Eye Color: blue FILM THE END Supporting Dir. Anthony Jerjen THIS IS HOW YOU DIE Supporting Dir. Michael Mohan SPRAYED Supporting Dir. Jacqueline Richards PARAMECIUM PETE Lead Dir. Kathryn Fuss THE BEST MAN Supporting Dir. Justin Lazernik TELEVISION/WEB THAT’S WHAT SHE SAID Guest Star Dir. Ryan Kelly & Andrew Heder EAGLES FANS Guest Star Dir. Ryan Kelly & Andrew Heder THE MAN WHO CREATED THE EMOJI Co-star Dir. Ryan Kelly & Andrew Heder OPEN HOUSE Guest Star Dir. Erin Hees SURPRIZE TEAM Series Regular Dir. Russell Ford CO-WORKERS Guest Star Dir. Nick Corirossi COMMERCIAL MAKESPACE Principal Dir. Gaelan Draper DORITOS Principal Dir. Andrew Adams SHARPIE Principal Dir. Danny Foxx POWERING CALIFORNIA Voiceover Dir. Trent Stockton POWERING CALIFORNIA Host Dir. Trent Stockton IMPROV/SKETCH SECOND CITY Hollywood, CA Undateable IMPROV OLYMPIC Chicago, IL Improv Graduate WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA Mission Improvable WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA Bear Supply WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA Cobranauts WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA The Diary Show SF SKETCHFEST San Francisco, CA Festival Show L.A. IMPROV FESTIVAL Hollywood, CA Festival show JUST THE FUNNY Miami, FL Festival show LAS VEGAS IMPROV FESTIVAL Las Vegas, NV Festival Show TRAINING Lesly Kahn Los Angeles, CA Work Session The Groundlings Hollywood, CA Improv - Core Track Second City Hollywood, CA Conservatory Program iO (Improv Olympic) Chicago, IL Improv Graduate M.I.’s Westside Comedy Theater Santa Monica, CA Instructor/Improv Graduate AK Studios LA Los Angeles, CA Acting/Commercial Workshops SPECIAL SKILLS Voice and Speech - English, Russian, Mexican Spanish and German accents; various impressions Weaponry - Glock 17 (on-set) Athletics - Basketball, Soccer, Frisbee, Volleyball and Cycling; Licensed driver . -

MICHIGAN MONTHLY ______January/Feb

MICHIGAN MONTHLY ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ January/Feb. 2020 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DETROIT RED WINGS – LITTLE CAESARS DETROIT PISTONS – LITTLE CAESAR’S ARENA ARENA – on FSD unless otherwise stated Jan. 2 at L.A. Clippers; 10:30 pm Jan. 3 at Dallas Stars; 8:30 pm Jan. 4 at Golden State Warriors; 8:30 pm Jan. 5 at Chicago Blackhawks; 7:30 pm Jan. 5 at L.A. Lakers; 10 pm Jan. 7 vs. Montreal Canadiens; 7:30 pm Jan. 7 at Cleveland Cavaliers; 7 pm Jan. 10 vs. Ottawa Senators; 7:30 pm Jan. 9 vs. Cleveland Cavaliers; 7 pm Jan. 12 vs. Buffalo Sabres; 5 pm Jan. 11 vs. Chicago Bulls; 7 pm Jan. 14 at New York Islanders; 7 pm Jan. 13 vs. New Orleans Pelicans; 7 pm Jan. 17 vs. Pittsburgh Penguins; 7:30 pm Jan. 15 at Boston Celtics; 7 pm Jan. 18 vs. Florida Panthers; 7 pm Jan. 18 at Atlanta Hawks; 7:30 pm Jan. 20 at Colorado Avalanche; 3 pm Jan. 20 at Washington Wizards; 2 pm Jan. 22 at Minnesota Wild; 8 pm Jan. 22 vs. Sacramento Kings; 7 pm Jan. 31 at New York Rangers; 7 pm Jan. 24 vs. Memphis Grizzlies; 7 pm Feb. 1 vs. New York Ranges; 7 pm Jan. 25 vs. Brooklyn Nets; 7 pm Feb. 3 vs. Philadelphia Flyers; 7:30 pm Jan. 27 vs. Cleveland Cavaliers; 7 pm Feb. 6 at Buffalo Sabres; 7 pm Jan. 29 at Brooklyn Nets; 7:30 pm; ESPN Feb. 7 at Columbus Blue Jackets; 7 pm Jan. 31 vs. Toronto Raptors; 7 pm Feb. -

The Life and Times of Phil Hartman

8VVS56RSSMZ3 \ Kindle # You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman Y ou Migh t Remember Me: Th e Life and Times of Ph il Hartman Filesize: 2.39 MB Reviews This ebook can be worth a read, and superior to other. Yes, it is actually perform, nonetheless an amazing and interesting literature. Your daily life period will probably be convert as soon as you comprehensive reading this article ebook. (Elisha O'Conner II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA DZ5PG9YIGAHQ < Kindle \ You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman YOU MIGHT REMEMBER ME: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF PHIL HARTMAN To get You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman PDF, you should access the hyperlink beneath and download the document or get access to additional information that are related to YOU MIGHT REMEMBER ME: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF PHIL HARTMAN ebook. Audible Studios on Brilliance, 2016. CD-Audio. Condition: New. Unabridged. Language: English . Brand New. Beloved TV comedic actor Phil Hartman is best known for his eight brilliant seasons on Saturday Night Live, where his versatility and comedic timing resulted in some of the funniest and most famous sketches in the television show s history. Besides his hilarious impersonations of Phil Donahue, Frank Sinatra and Bill Clinton, Hartman s other indelible characters included Cirroc the Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer, Eugene the Anal Retentive Chef and, of course, Frankenstein. He also starred as pompous radio broadcaster Bill McNeal in the NBC sitcom NewsRadio and voiced numerous classic roles--most memorably washed-up actor and commercial pitchman Troy McClure--on Fox s long-running animated hit The Simpsons. -

'Live from New York'

Thursday, October 11, 2018 • APG News B5 5 2 0 part of the cast for _______ years. 9. He served as the original anchor for the “Weekend Update” segment of “Saturday - + ( 19. She was the first woman to host Night Live.” % “Saturday Night Live.” 11. Colin Jost and _________ currently serve as 20. “The Unfrozen Caveman __________,” was a co-anchors on the recurring “SNL” sketch # recurring character created by Jack Handey “Weekend Update.” " 5! and played by Phil Hartman on “Saturday 55 Night Live” from 1991 through 1996. 13. Actor Alec Baldwin has hosted “Saturday Night Live” more than anyone else, _________ 52 50 21. This original “SNL” cast member played a times between 1990 and 2017. 5- samurai in several sketches. 16. “Saturday TV________” was the title of a 5+ 23. Enid Strict, better known as “The recurring skit on “Saturday Night Live” 5( 5% _________Lady”, is a recurring character from featuring cartoons created by “SNL” writer aseries of sketches on “Saturday Night Live,” Robert Smigel. that was created and played by cast 5# 5" member Dana Carvey. 17. This comedian was the first to host 2! “Saturday Night Live,” in the debut October 25 24. An “SNL” episode normally begins with a 1975 episode. ________ open sketch that ends with 22 20 someone breaking character and 18. This co-creator and writer of the hit NBC 2- proclaiming, “Live from New Yo rk, it’s show “Seinfeld” briefly wrote for “SNL.” Saturday Night!” 2+ 19. This current “SNL” cast member has 2( 25. “The Boston __________” are fictional impersonated celebrities like Roseanne Barr, characters featured on “Saturday Night Live,” Meghan Trainor, Rebel Wilson and Adele. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

PRODUCTION INFORMATION Michelangelo, Donatello, Leonardo, and Raphael Return to Theaters This Summer to Battle Bigger, Badder Vi

PRODUCTION INFORMATION Michelangelo, Donatello, Leonardo, and Raphael return to theaters this summer to battle bigger, badder villains, alongside April O’Neil (Megan Fox), Vern Fenwick (Will Arnett), and a newcomer: the hockey-masked vigilante Casey Jones (Stephen Amell). After supervillain Shredder (Brian Tee) escapes custody, he joins forces with mad scientist Baxter Stockman (Tyler Perry) and two dimwitted henchmen, Bebop (Gary Anthony Williams) and Rocksteady (WWE Superstar Stephen “Sheamus” Farrelly), to unleash a diabolical plan to take over the world. As the Turtles prepare to take on Shredder and his new crew, they find themselves facing an even greater evil with similar intentions: the notorious Krang. Paramount Pictures and Nickelodeon Movies present a Platinum Dunes Production , A Gama Entertainment / Mednick Production / Smithrowe Entertainment Production, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows. The film is directed by Dave Green (Earth to Echo) , written by Josh Appelbaum & André Nemec (Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol) and produced by Michael Bay (the blockbuster Transformers franchise, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles), Andrew Form, Brad Fuller, Galen Walker and Scott Mednick. The executive producers are Denis L. Stewart, Grant Curtis, Eric Crown and Napoleon Smith III, André Nemec and Josh Appelbaum. The film stars Megan Fox, Will Arnett, Laura Linney, Stephen Amell, Noel Fisher, Jeremy Howard, Pete Ploszek, Alan Ritchson, and Tyler Perry. Rounding out the cast are Brian Tee, Stephen “Sheamus” Farrelly, Gary Anthony Williams, Brittany Ishibashi and Jane Wu. A NEW DIMENSION “Our story begins where the first film ends, in real life and in the movie,” says producer Andrew Form. -

The Creative Life of 'Saturday Night Live' Which Season Was the Most Original? and Does It Matter?

THE PAGES A sampling of the obsessive pop-culture coverage you’ll find at vulture.com ost snl viewers have no doubt THE CREATIVE LIFE OF ‘SATURDAY experienced Repetitive-Sketch Syndrome—that uncanny feeling NIGHT LIVE’ WHICH Mthat you’re watching a character or setup you’ve seen a zillion times SEASON WAS THE MOST ORIGINAL? before. As each new season unfolds, the AND DOES IT MATTER? sense of déjà vu progresses from being by john sellers 73.9% most percentage of inspired (A) original sketches season! (D) 06 (B) (G) 62.0% (F) (E) (H) (C) 01 1980–81 55.8% SEASON OF: Rocket Report, Vicki the Valley 51.9% (I) Girl. ANALYSIS: Enter 12 51.3% new producer Jean Doumanian, exit every 08 Conehead, Nerd, and 16 1975–76 sign of humor. The least- 1986–87 SEASON OF: Samurai, repetitive season ever, it SEASON OF: Church Killer Bees. ANALYSIS: taught us that if the only Lady, The Liar. Groundbreaking? breakout recurring ANALYSIS: Michaels Absolutely. Hilarious? returned in season 11, 1990–91 character is an unfunny 1982–83 Quite often. But man-child named Paulie dumped Billy Crystal SEASON OF: Wayne’s SEASON OF: Mr. Robinson’s unbridled nostalgia for Herman, you’ve got and Martin Short, and Neighborhood, The World, Hans and Franz. SNL’s debut season— problems that can only rebuilt with SNL’s ANALYSIS: Even though Whiners. ANALYSIS: Using the second-least- be fixed by, well, more broadest ensemble yet. seasons 4 and 6 as this is one of the most repetitive ever—must 32.0% Eddie Murphy. -

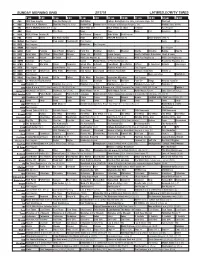

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min. -

Thesis Vol.2 5:23:18

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Performance of Play Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2rj918rh Author Jones, Lauren Brianna Publication Date 2018 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2rj918rh#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO The Performance of Play, Lauren Jones A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Music by Lauren Jones Committee in charge: Professor Susan Narucki, Chair Professor Sarah Hankins Professor Stephanie Richards 2018 The Thesis of Lauren Jones is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………iv List of Supplemental Videos………………………………………………………………………v Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………….vi Epigraph………………………………………………………………………………………… vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………………...viii Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….1 Play as a Creative State……………………………………………………………………………4 Pee-wee’s Playhouse: A Performance of Play………………………………………………….. 11 Pocket Music………………….……………………………………………………………….....17 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 References…………………………………………………………………………………...…...23 iv LIST OF SUPPLEMENTAL VIDEOS jones_01_bossy_screen.wav -

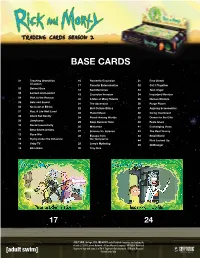

Rick and Morty Season 2 Checklist

TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 BASE CARDS 01 Teaching Grandkids 16 Romantic Excursion 31 Emo Streak A Lesson 17 Parasite Extermination 32 Get It Together 02 Behind Bars 18 Bad Memories 33 Teen Angst 03 Locked and Loaded 19 Cromulon Invasion 34 Important Member 04 Rick to the Rescue 20 A Man of Many Talents 35 Human Wisdom 05 Safe and Sound 21 The Ascension 36 Purge Planet 06 No Code of Ethics 22 Bird Culture Ethics 37 Aspiring Screenwriter 07 Roy: A Life Well Lived 23 Planet Music 38 Going Overboard 08 Silent But Deadly 24 Peace Among Worlds 39 Dinner for the Elite 09 Jerryboree 25 Keep Summer Safe 40 Feels Good 10 Racial Insensitivity 26 Miniverse 41 Exchanging Vows 11 Beta-Seven Arrives 27 Science Vs. Science 42 The Real Tammy 12 Race War 28 Escape from 43 Small World 13 Flying Under the Influence the Teenyverse 44 Rick Locked Up 14 Unity TV 29 Jerry’s Mytholog 45 Cliffhanger 15 Blim Blam 30 Tiny Rick 17 24 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. A Time Warner Company. All Rights Reserved. Cryptozoic logo and name is a TM of Cryptozoic Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 CHARACTERS chase cards (1:3 packs) C1 Unity C7 Mr. Poopybutthole C2 Birdperson C8 Fourth-Dimensional Being C3 Krombopulos Michael C9 Zeep Xanflorp C4 Fart C10 Arthricia C5 Ice-T C11 Glaxo Slimslom C6 Tammy Gueterman C12 Revolio Clockberg Jr. C1 C3 C9 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network.