Valleys Taskforce: Stakeholders Interviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc Version 5 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Treorchy is a town and electoral ward in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf in the Rhondda Fawr valley. Treorchy is one of the 16 communities that make up the Rhondda. Treorchy is bordered by the villages of Cwmparc and Ynyswen which are included within the profile. The population is 7,694, 4,404 of which are working age. Treorchy has a thriving high street with many shops and cafes and is in the running as one of the 3 Welsh finalists for Highs Street of the Year award. There are 2 large supermarkets and an Treorchy High Street industrial estate providing local employment. There is also a High school with sixth form Cwmparc Community Centre opportunities for young people in the area Cwmparc is a village and district of the community of Treorchy, 0.8 miles from Treorchy. It is more of a residential area, however St Georges Church Hall located in Cwmparc offers a variety of activities for the community, including Yoga, playgroup and history classes. Ynyswen is a village in the community of Treorchy, 0.6 miles north of Treorchy. It consists mostly of housing but has an industrial estate which was once the site of the Burberry’s factory, one shop and the Forest View Medical Centre. Although there are no petrol stations in the Treorchy area, transport is relatively good throughout the valley. However, there is no Sunday bus service in Cwmparc. Treorchy has a large population of young people and although there are opportunities to engage with sport activities it is evident that there are fewer affordable activities for young women to engage in. -

COMMUNITY COORDINATOR BULLETIN March 2018

COMMUNITY COORDINATOR BULLETIN March 2018 CONTENTS Rhondda Valleys Page no. 2 Cynon Valley 4 Taff Ely 5 Merthyr Tydfil 6 Health 7 Cwm Taf general information 8 1 Rhondda Valleys Contact: Meriel Gough Tel: 07580 865938 or email: [email protected] Seasons Dance Spring Sequence Dance th Tuesday 6 March 2-4pm, NUM Tonypandy, Llwynypia Rd. Live music with an organist. Bar will be open for light refreshments. Entry £2. Everyone Welcome. Contact Lynda: 07927 038 922 Over 50’s Walking Group Maerdy Every Thursday from 10:30am – 12:30pm at Teify House, Station Terrace, Maerdy, Ferndale, CF43 4BE You’re sure of a friendly welcome! To find out more call 0800 161 5780 or email [email protected] Walking Football Programme in Clydach Vale This is a new programme: The group meet at 11am until noon every Tuesday at the 3G pitch Clydach Vale.Qualified Coaches oversee the group. Everyone welcome! The first three visits are free and then £2 each thereafter. Contact Cori Williams 01443 442743 / 07791 038918 email: [email protected] Actif Woods Treherbert: Come and try out some woodland activities for FREE! 12-week woodland activity programmes in the Treherbert/RCT area. sessions are run by Woodland Leaders and activities are for Carers and people aged 54+ Come and try out some woodland activities, learn new skills, meet new people and see how woodlands can benefit you! Woodland activities range from short, easy walks, woodland crafts to basic bushcraft skills and woodland management. All activities will be tailored to suit the abilities and needs of the group. -

Inspection Report Pontrhondda Primary School Eng 2012

A report on Pontrhondda Primary School, Pontrhondda Road, Llwynypia, Tonypandy, CF40 2SZ Date of inspection: May 2012 by Dr David Gareth Evans for Estyn, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate for Education and Training in Wales During each inspection, inspectors aim to answer three key questions: Key Question 1: How good are the outcomes? Key Question 2: How good is provision? Key Question 3: How good are leadership and management? Inspectors also provide an overall judgement on the school’s current performance and on its prospects for improvement. In these evaluations, inspectors use a four-point scale: Judgement What the judgement means Excellent Many strengths, including significant examples of sector-leading practice Good Many strengths and no important areas requiring significant improvement Adequate Strengths outweigh areas for improvement Unsatisfactory Important areas for improvement outweigh strengths The report was produced in accordance with Section 28 of the Education Act 2005. Every possible care has been taken to ensure that the information in this document is accurate at the time of going to press. Any enquiries or comments regarding this document/publication should be addressed to: Publication Section Estyn Anchor Court, Keen Road Cardiff CF24 5JW or by email to [email protected] This and other Estyn publications are available on our website: www.estyn.gov.uk © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012: This report may be re-used free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is re-used accurately and not used in a misleading context. The copyright in the material must be acknowledged as aforementioned and the title of the report specified. -

120 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

120 bus time schedule & line map 120 Blaencwm - Caerphilly via Porth View In Website Mode The 120 bus line (Blaencwm - Caerphilly via Porth) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blaen-Cwm: 6:12 AM - 8:15 PM (2) Caerphilly: 6:32 AM - 7:08 PM (3) Pontypridd: 6:40 PM (4) Porth: 7:20 AM - 9:30 PM (5) Porth: 3:35 PM - 9:13 PM (6) Tonypandy: 5:25 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 120 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 120 bus arriving. Direction: Blaen-Cwm 120 bus Time Schedule 103 stops Blaen-Cwm Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:05 AM - 4:05 PM Monday 6:12 AM - 8:15 PM Interchange, Caerphilly Station Terrace, Caerphilly Tuesday 6:12 AM - 8:15 PM South Gate Square, Caerphilly Wednesday 6:12 AM - 8:15 PM Cardiff Road, Caerphilly Thursday 6:12 AM - 8:15 PM Castle Entrance, Caerphilly Friday 6:12 AM - 8:15 PM The Piccadilly (Nantgarw Road), Caerphilly Saturday 6:12 AM - 8:15 PM 3 Nantgarw Road, Caerphilly Crescent Road, Caerphilly Aber Station, Caerphilly 120 bus Info Direction: Blaen-Cwm Martin's Farm, Caerphilly Stops: 103 Trip Duration: 111 min Cwrt Rawlin Inn, Caerphilly Line Summary: Interchange, Caerphilly, South Gate Nantgarw Road, Caerphilly Square, Caerphilly, Castle Entrance, Caerphilly, The Piccadilly (Nantgarw Road), Caerphilly, Crescent Cwrt Rawlin School, Castle View Road, Caerphilly, Aber Station, Caerphilly, Martin's Farm, Caerphilly, Cwrt Rawlin Inn, Caerphilly, Cwrt Clos Enfys, Castle View Rawlin School, Castle View, Clos Enfys, Castle View, Ffordd Traws Cwm, Caerphilly -

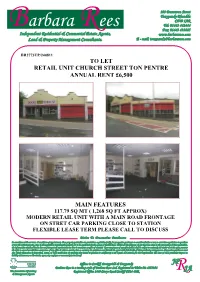

R JA Barbara Rees

103 Dunraven Street Tonypandy Rhondda CF40 1AR arbara ees Tel: 01443 442444 B R Fax: 01443 433885 Independent Residential & Commercial Estate Agents, www.barbararees.com Land & Property Management Consultants. E - mail; [email protected] BR2773TP/240811 TO LET RETAIL UNIT CHURCH STREET TON PENTRE ANNUAL RENT £6,500 MAIN FEATURES 117.79 SQ MT ( 1,268 SQ FT APPROX) MODERN RETAIL UNIT WITH A MAIN ROAD FRONTAGE ON STRET CAR PARKING CLOSE TO STATION FLEXIBLE LEASE TERM PLEASE CALL TO DISCUSS Notice To Prospective Purchasers In accordance with our terms & conditions of appointment, these property particulars are provided as a guideline (only), for prospective purchasers to consider whether or not, to enter into negotiations to purchase or rent the subject property. Any & all negotiations regarding the property are to be conducted via the agency of Barbara Rees. Whilst all due diligence & care has been taken in the preparation of these particulars, the information contained herein does not form part of any contract nor does it constitute an offer of contract. Upon acceptance of any offer (which shall be subject to contract), the vendor & or the agent, reserves the right to amend or withdraw acceptance of any offer & prior to entering into a contract, the purchaser must furnish the agent with full details of their purchasing arrangements. Prospective purchasers must also satisfy themselves by inspection, survey, or other means that the property they intend to purchase is satisfactory in all regards and suitable for their requirements. The issue of these particulars impose no liability whatsoever, on the vendor, agent, any employee or connected person thereof. -

Weekly-List-Published-05-October

CYNGOR BWRDEISTREF SIRIOL RHONDDA CYNON TAF - Page 1 of 10 RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL WARD : Aberaman North Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/1063/08 [RP] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Single storey extension & step lift to access rear garden. Arfaethedig / Proposal: Lleoliad / Location: 2 BEDDOE STREET, ABERAMAN, ABERDAR, CF44 6UP ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / CONTACT Cyfeirnodau CONTACT NAME AND ADDRESS NAME AND ADDRESS Grid / Grid Mr P Watts e: 301263 Rhondda Cynon Taf Council Housing Grants n: 201567 Sardis House Sardis Road, Pontypridd CF37 1DU WARD : Church Village Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/1055/10 [RP] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Construction of a single storey extension. Arfaethedig / Proposal: Lleoliad / Location: 13 DYFFRYN Y COED, CHURCH VILLAGE, PONTYPRIDD, CF38 1PJ ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / CONTACT Cyfeirnodau CONTACT NAME AND ADDRESS NAME AND ADDRESS Grid / Grid Mr M Camilleri Mr & Mrs Scofield e: 308862 Cardiff Orangeries 13 The Coach House Dyffryn Y Coed n: 185541 The Common Church Village Whitchurch Pontypridd Cardiff CF38 1PJ CF14 1DW Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/1059/10 [RP] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Single storey rear extension. Arfaethedig / Proposal: Lleoliad / Location: 1 PEN-YR-EGLWYS, CHURCH VILLAGE, PONTYPRIDD, CF38 1UA ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / CONTACT Cyfeirnodau CONTACT NAME AND ADDRESS NAME AND ADDRESS Grid / Grid Mr Paul Rees Mr J Burnell e: 308169 3 Heol-y-Parc 1 Pen-yr-Eglwys Efail Isaf Church Village n: 186427 Pontypridd Pontypridd CF38 1AN CF38 1UA WARD : Cilfynydd Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/0708/10 [JE] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Change of use of land to extend garden curtilage (retrospective) (Amended Plans Arfaethedig / Received 14/09/18). -

Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS REPORT AND PROPOSALS COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 3. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 4. DRAFT PROPOSALS 5. REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 6. ASSESSMENT 7. PROPOSALS 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT APPENDIX 1 GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDIX 2 EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 3 PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 4 MINISTER’S DIRECTIONS AND ADDITIONAL LETTER APPENDIX 5 SUMMARY OF REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO DRAFT PROPOSALS The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk FOREWORD This is our report containing our Final Proposals for Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council. In January 2009, the Local Government Minister, Dr Brian Gibbons asked this Commission to review the electoral arrangements in each principal local authority in Wales. Dr Gibbons said: “Conducting regular reviews of the electoral arrangements in each Council in Wales is part of the Commission’s remit. The aim is to try and restore a fairly even spread of councillors across the local population. It is not about local government reorganisation. Since the last reviews were conducted new communities have been created in some areas and there have been shifts in population in others. -

Community Profile – Treherbert, Blaencwm, Blaenrhondda, Tynewydd and Penyrenglyn

Community Profile – Treherbert, Blaencwm, Blaenrhondda, Tynewydd and Penyrenglyn Version 6 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Treherbert is a village and community situated at the head of the Rhondda Fawr valley in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales. Treherbert is a former industrial coal mining village which was at its economic peak between 1850 and 1920. Treherbert is the upper most community of the Rhondda Fawr and encompasses the districts of Blaencwm, Blaenrhondda, Tynewydd and Pen-yr-englyn. Blaen-y-Cwm and Blaenrhondda are at the head the Rhondda Fawr valley. With Treherbert, Tynewydd, Blaencwm, Blaenrhondda and Pen-yr-englyn it is part of a community of Treherbert. Rhondda Fawr is the larger of the Rhondda Valleys. Treherbert mural on the corner of Station street Dunraven Hotel as you approach the railway station. The entire upper Rhondda has beautiful outdoor green spaces and although each village is its own community as they mostly run straight into each other communities are well linked. There are very few shops in Tynewydd, Blaencwm and Blaenrhondda but Treherbert has an active busy high street. Whilst there is a lack of variety of activities for young people the very close proximity of towns and village in the Rhondda Fawr mean that people from Treherbert to Blaencwm drive through / visit Treorchy which is the main hub of the Upper Rhondda on almost a daily basis. The Welcome to our Woods, Create Your Space Programme is a long-term Lottery funded placed based approach to supporting the community improve health and wellbeing and the local economy through better use of the natural assets in the Upper Rhondda working to connect villages - the activities taking place in the area, especially the Welcome to Our Woods activities are connecting people living in the local villages. -

Glamorgan's Blood

Glamorgan’s Blood Colliery Records for Family Historians A Guide to Resources held at Glamorgan Archives Front Cover Illustrations: 1. Ned Griffiths of Coegnant Colliery, pictured with daughters, 1947, DNCB/14/4/33/6 2. Mr Lister Warner, Staff Portrait, 8 Feb 1967 DNCB/14/4/158/1/8 3. Men at Merthyr Vale Colliery, 7 Oct 1969, DNCB/14/4/158/2/3 4. Four shaft sinkers in kibble, [1950s-1960s], DNCB/14/4/158/2/4 5. Two Colliers on Surface, [1950s-1960s], DNCB/14/4/158/2/24 Contents Introduction 1 Summary of the collieries for which Glamorgan Archives hold 3 records containing information on individuals List of documents relevant to coalfield family history research 6 held at Glamorgan Archives (arranged by the valley/area) Collieries in Aber Valley 6 Collieries in Afan Valley 6 Collieries in Bridgend 8 Collieries in Caerphilly 9 Collieries in Clydach Vale 9 Collieries in Cynon Valley 10 Collieries in Darren Valley 11 Collieries in Dowlais/Merthyr 13 Collieries in Ebbw Valley 15 Collieries in Ely Valley 17 Collieries in Garw Valley 17 Collieries in Ogmore Valley 19 Collieries in Pontypridd 21 Collieries in Rhondda Fach 22 Collieries in Rhondda Fawr 23 Collieries in Rhondda 28 Collieries in Rhymney Valley 29 Collieries in Sirhowy Valley 32 Other (non-colliery) specific records 33 Additional Sources held at Glamorgan Archives 42 External Resources 43 Introduction At its height in the early 1920s, the coal industry in Glamorgan employed nearly 180,000 people - over one in three of the working male population. Many of those tracing their ancestors in Glamorgan will therefore sooner or later come across family members who were coal miners or colliery surface workers. -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY the History of the Jewish Diaspora in Wales Parry-Jones

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The history of the Jewish diaspora in Wales Parry-Jones, Cai Award date: 2014 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Contents Abstract ii Acknowledgments iii List of Abbreviations v Map of Jewish communities established in Wales between 1768 and 1996 vii Introduction 1 1. The Growth and Development of Welsh Jewry 36 2. Patterns of Religious and Communal Life in Wales’ Orthodox Jewish 75 Communities 3. Jewish Refugees, Evacuees and the Second World War 123 4. A Tolerant Nation?: An Exploration of Jewish and Non-Jewish Relations 165 in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Wales 5. Being Jewish in Wales: Exploring Jewish Encounters with Welshness 221 6. The Decline and Endurance of Wales’ Jewish Communities in the 265 Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries Conclusion 302 Appendix A: Photographs and Etchings of a Number of Wales’ Synagogues 318 Appendix B: Images from Newspapers and Periodicals 331 Appendix C: Figures for the Size of the Communities Drawn from the 332 Jewish Year Book, 1896-2013 Glossary 347 Bibliography 353 i Abstract This thesis examines the history of Jewish communities and individuals in Wales. -

Gwendoline Street, Treherbert, Treorchy, Rhondda, Cynon, Taff

Gwendoline Street, Treherbert, Treorchy, Rhondda, Cynon, Taff. CF42 5BW 65,000 • No Chain • Mid Terrace • 3 Bedrooms • Lounge • Kitchen • Ground Floor Bathroom • Rear Garden • Close To Local Aminities • Combi Boiler Ref: PRA10632 Viewing Instructions: Strictly By Appointment Only General Description Call the office to arrange to view this 3 bed, mid terrace property situated in Treherbert, This property comprises of 3 bedrooms, lounge, kitchen, ground floor bathroom and enclosed rear garden. This property is ideally located close to amenities and benefits from beautiful views. No Chain. Accommodation Entrance Upvc door leading to porch area, wood panels on walls, textured ceiling, fitted carpet, cupboard housing consumer unit and access to lounge. Lounge (21' 10" x 14' 5") or (6.66m x 4.39m) 2 Upvc double glazed windows to front and rear, plastered walls, textured ceiling, fitted carpet, under stair storage cupboard, gas fire and surround, radiator, power points and access to stairs and kitchen. Kitchen (14' 3" x 8' 10") or (4.34m x 2.70m) Upvc double glazed window to side, tiled and plastered walls, textured ceiling, vinyl flooring, fitted wall and base units with integrated stainless steel sink and drainer unit, gas hob, electric oven, extractor fan, cupboard housing combi boiler, space for white goods, radiator, power points and access to ground floor bathroom and rear garden. Ground Floor Bathroom 2 Upvc double glazed windows to rear, tiled walls, textured ceiling, vinyl flooring, panel bath with overhead shower, low level W/C, pedestal sink, radiator and access to loft. Landing Upvc double glazed window to rear, plastered walls, textured ceiling, fitted carpet, built in storage cupboards, radiator, power points, access to loft and bedrooms. -

Members Interests - March 2019

Glamorgan Family History Society - Members Interests - March 2019 Mem Surname Place County Date Range No ABRAHAM (Any) Llansamlet/Swansea GLA All 6527 ABRAHAM Griffith Llansamlet (Bargeman) GLA 1775+ 6527 ABRAHAMS Florence May Bedminster Bristol -Born 1896? GLA -1962 6126 ACE Reynoldston GLA All 6171 ACE Bridgend GLA ANY 3143 ACE Samuel Gower GLA 1750 - 1795 5302 ACE Samuel Swansea / Llanelli CMN 1827 – 1879 10353 ACE Thomas Gower – Swansea GLA 1783 – 1823 10353 ACTESON all GLA 1860- 5566 ACTESON Elizabeth Pant St. St Thomas S'ea GLA 1870 - 1960 5433 ADAMS Glamorgan GLA 1800+ 4631 ADAMS John Lewis Haverfordwest GLA c1845 3536 ADDICOTT Job North Petherton & Cowbridge SOM 1837 - 1919 5931 AHERNE Aberdare GLA 1865+ 3667 ALISON Bertha Halstead Milnsbridge YKS 1878+ 6163 ALLAN Albina Llanelli CMN 1901+ 9235 ALLAN Evelyn Loughor GLA 1901+ 9235 ALLAN Frederick Gowerton GLA 1901+ 9235 ALLAN Lotty Gowerton GLA 1901+ 9235 ALLAN Winnie Llanelli CMN 1901+ 9235 ALLAN Maggie Llanelli CMN 1901+ 9235 ALLEN Cardiff GLA 1860 - 1910 4159 ALLEN Aberdare - Cardiff GLA 1840 - 1900 5191 ALLEN Aaron Glamorgan GLA 1858+ 10344 ALLEN Aaron Glamorgan GLA 1858+ 10344 ALLEN Edwin` Birmingham WAR 1791 - 1860 8382 ALLEN Mary Ann Cardiff - Whitchurch GLA 1870 - 1900 6150 ALLEN Mary Jane Newport MON 1852+ 6488 ALLEN William Birmingham WAR 1818 – 1880 8382 ALLIN / ALLEYN Devon DEV 1750-1900 3210 ALLIN / ALLEYN Neath, Swansea GLA 1750-1900 3210 ALLRIGHT Elizabeth Mapledurnell HAM 1700+ 5590 ANDERSON Ann(e) Cowbridge GLA 1806-1862 10499 ANDERSON Ann(e) Newport MON 1806-1862