Why Wilderness?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2018 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2018 As of September 30, 2018 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover photo courtesy of: Chris Chavez Statistics are current as of: 10/15/2018 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,948,059 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 506 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 128 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 446 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The FS also administers several other types of nationally-designated areas: 1 National Historic Area in 1 State 1 National Scenic Research Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Recreation Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Wildlife Area in 1 State 2 National Botanical Areas in 1 State 2 National Volcanic Monument Areas in 2 States 2 Recreation Management Areas in 2 States 6 National Protection Areas in 3 States 8 National Scenic Areas in 6 States 12 National Monument Areas in 6 States 12 Special Management Areas in 5 States 21 National Game Refuge or Wildlife Preserves in 12 States 22 National Recreation Areas in 20 States Table of Contents Acreage Calculation ........................................................................................................... -

TCWP Newsletter No

TENNESSEE CITIZENS for WILDERNESS PLANNING Newsletter No. 214 January 19, 1997 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1. Big South Fork .. P· 4 A. GMP under w.ty B. Oppose Beu CrHk landfill C Black bears 2. Obed Wilier news ........................ p.4 A. Oear Creek Dam study near end C. Objective: Stale ONRW designation B. Obed selected for national program D. Water Resour'e Mngt Plan 3. State parks and other state lands .. .. .. p. S A. St.tle Parks reform initiative C. Appeal stripmine .tdjacent to Frozen Head B. Support Fall Creek Falls protection D. Acquisitions of state lands 4. The Tennessee legislature .. P· 7 A. Makeup of new General Assembly C Forestry legisl.ttion B. Gilbert's Stale Pnks bill D. Beverilgeo<ontainer deposit l.lw 5. Othersl.tle news .. P· 8 A. Scotts Gulf update D. Greenw�ys B. Sequatchie Valley pump stouge: E. Stripmine de�nup very slow pl�n ch�nged, project still b�d F. Upper Clinch conservation efforts C Ch�nge in Administr�tion G. Tenn.'s new feder�lly endangered plant 6. Smokies (�!so see 112F) .................... P· 9 A. C�t�loochee development concepts B. Cochran Creek acquisition 7. Cherokee National Forest... p.10 A. Ocoee Natl. Rea. Area? B. Appeal Cherokee decision C. Report on USFS 8. TVA's Duck River EIS and other maHers . p. 11 A. F�te of lands acquired for deceased Columbia Dam C Law forbids dock fees B. St�le: TVA recommending too much development D. Wamp heads uucus 9. Prospects for the new Congress. , , .. .. .. .. p. 12 A. Environment �nd election B. -

Where to Go Camping Guidebook

2010 Greater Alabama Council Where to Go Camp ing Guidebook Published by the COOSA LODGE WHERE TO GO CAMPING GUIDE Table of Contents In Council Camps 2 High Adventure Bases 4 Alabama State Parks 7 Georgia State Parks 15 Mississippi State Parks 18 Tennessee State Parks 26 Wildlife Refuge 40 Points of Interest 40 Wetlands 41 Places to Hike 42 Sites to See 43 Maps 44 Order of the Arrow 44 Future/ Wiki 46 Boy Scouts Camps Council Camps CAMPSITES Each Campsite is equipped with a flagpole, trashcan, faucet, and latrine (Except Eagle and Mountain Goat) with washbasin. On the side of the latrine is a bulletin board that the troop can use to post assignments, notices, and duty rosters. Camp Comer has two air-conditioned shower and restroom facilities for camp-wide use. Patrol sites are pre-established in each campsite. Most campsites have some Adarondaks that sleep four and tents on platforms that sleep two. Some sites may be occupied by more than one troop. Troops are encouraged to construct gateways to their campsites. The Hawk Campsite is a HANDICAPPED ONLY site, if you do not have a scout or leader that is handicapped that site will not be available. There are four troop / campsites; each campsite has a latrine, picnic table and fire ring. Water may be obtained at spigots near the pavilion. Garbage is disposed of at the Tannehill trash dumpster. Each unit is responsible for providing its trash bags and taking garbage to the trash dumpster. The campsites have a number and a name. Make reservations at a Greater Alabama Council Service Center; be sure to specify the campsite or sites desired. -

Draft Small Vessel General Permit

ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, COASTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAM PUBLIC NOTICE The United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region 5, 77 W. Jackson Boulevard, Chicago, Illinois has requested a determination from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources if their Vessel General Permit (VGP) and Small Vessel General Permit (sVGP) are consistent with the enforceable policies of the Illinois Coastal Management Program (ICMP). VGP regulates discharges incidental to the normal operation of commercial vessels and non-recreational vessels greater than or equal to 79 ft. in length. sVGP regulates discharges incidental to the normal operation of commercial vessels and non- recreational vessels less than 79 ft. in length. VGP and sVGP can be viewed in their entirety at the ICMP web site http://www.dnr.illinois.gov/cmp/Pages/CMPFederalConsistencyRegister.aspx Inquiries concerning this request may be directed to Jim Casey of the Department’s Chicago Office at (312) 793-5947 or [email protected]. You are invited to send written comments regarding this consistency request to the Michael A. Bilandic Building, 160 N. LaSalle Street, Suite S-703, Chicago, Illinois 60601. All comments claiming the proposed actions would not meet federal consistency must cite the state law or laws and how they would be violated. All comments must be received by July 19, 2012. Proposed Small Vessel General Permit (sVGP) United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) SMALL VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS LESS THAN 79 FEET (sVGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act, as amended (33 U.S.C. -

1975/01/03 S3433 Eastern Wilderness” of the White House Records Office: Legislation Case Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 20, folder “1975/01/03 S3433 Eastern Wilderness” of the White House Records Office: Legislation Case Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Exact duplicates within this folder were not digitized. Digitized from Box 20 of the White House Records Office Legislation Case Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library ACTION THE WHITE HOUSE Last Day: January 4 WASHINGTON s January 2, 1975 I lot ?b ~ . () ,, , 5 MEMORANDUM FOR THE ~ESiiNT FROM: KEN~ SUBJECT: Enrolled Bill S. 3433 Eastern Wilderness Attached for your consideration is S. 3433, sponsored by Senator Aiken and 21 others, which designates 16 National Forest wilderness areas as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System. In addition, 17 National Forest areas would be studied as to their suitability or non-suitability for preservation as wilderness, and the President would be required to make his recommendations to Congress within five years. -

Hiking the Appalachian and Benton Mackaye Trails

10 MILES N # Chattanooga 70 miles Outdoor Adventure: NORTH CAROLINA NORTH 8 Nantahala 68 GEORGIA Gorge Hiking the Appalachian MAP AREA 74 40 miles Asheville co and Benton MacKaye Trails O ee 110 miles R e r Murphy i v 16 Ocoee 64 Whitewater Center Big Frog 64 Wilderness Benton MacKaye Trail 69 175 Copperhill TENNESSEE NORTH CAROLINA Appalachian Trail GEORGIA GEORGIA McCaysville GEORGIA 75 1 Springer Mountain (Trail 15 Epworth spur T 76 o 60 Hiwassee Terminus for AT & BMT) 2 c 2 5 c 129 Cohutta o Wilderness S BR Scenic RRa 60 Young 2 Three Forks F R Harris 288 iv e 3 Long Creek Falls r Mineral 14 Bluff Woody Gap 2 4 Mercier Brasstown 5 Neels Gap, Walasi-Yi Orchards F Bald S 64 13 Lake Morganton Blairsville Center Blue 515 17 6 Tesnatee Gap, Richard Ridge old Blue 76 Russell Scenic Hwy. Ridge 129 A s 7 Unicoi Gap k a 60 R oa 180 8 Toccoa River & Swinging Benton TrailMacKaye d 7 12 10 Bridge 9 Vogel 9 Wilscot Gap, Hwy 60 11 Cooper Creek State Park Scenic Area Shallowford Bridge Rich Mtn. 75 10 Wilderness 11 Stanley Creek Rd. 515 8 180 5 Toccoa 6 12 Fall Branch Falls 52 River 348 BMT Trail Section Distances (miles) 13 Dyer Gap (6.0) Springer Mountain - Three Forks 19 Helen (1.1) Three Forks - Long Creek Falls 3 60 14 Watson Gap (8.8) Three Forks - Swinging Bridge FS 15 Jacks River Trail Ellijay (14.5) Swinging Bridge - Wilscot Gap 58 Suches (7.5) Wilscot Gap - Shallowford Bridge F S Three (Dally Gap) (33.0) Shallowford Bridge - Dyer Gap 4 Forks 4 75 (24.1) Dyer Gap - US 64 2 2 Appalachian Trail 129 alt 16 Thunder Rock Atlanta 19 Campground -

Ocoee and Hiwassee Rivers Corridor Management Plan

USDA Ocoee and Hiwassee Rivers United States Department of Corridor Management Plan Agriculture Forest Service Region 8 Cherokee National Forest February 2008 Prepared by USDA Forest Service Center for Design & Interpretation The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. The Ocoee and Hiwassee Rivers Corridor Management Plan Prepared by _____________________________________________________________________________ Lois Ziemann, Interpretive Planner Date _____________________________________________________________________________ Sarah Belcher, Landscape Architect Date Recommended by _____________________________________________________________________________ Doug -

Coker Creek Falls 4

«¬101 ¤£27 «¬285 BLEDSOE icon legend STATE 12 waterfalls of FOREST !( SPRING CITY Watts Bar southeast tennessee Lake Safe to Swim (!8 «¬304 «¬58 8 Piney FALL CREEK FALLS River Leashed Dogs On the Cover: STATE PARK «¬68 Welcome ?? !( PIKEVILLE R H E A Photo courtesy of ?? Easy Hike (!119 Tennessee «¬30 River B L E D S O E «¬305 Moderate B L E D S O E !( DECATUR 56 !( NIOTA «¬ ¤£127 Hike !( DAYTON «¬307 Difficult BEERSHEBA SPRINGS «¬303 G R U N D Y !( «¬399 Hike 5 !( !( ATHENS !( SOUTH CUMBERLAND GRAYSVILLE ALTAMONT SAVAGE GULF !( Restrooms AREA «¬8 HIWASSEE 4 7 WILDLIFE M E II G S ENGLEWOOD 3 REFUGE «¬33 6 «¬39 !( !( DUNLAP !( PALMER 10 «¬111 !( ¤£11 «¬50 Chickamauga M C M II N N !( ETOWAH COALMONT S E Q U A T C H II E Lake «¬310 9 !( CALHOUN !( «¬163 «¬283 SODDY-DAISY CHARLESTON !( TRACY CITY «¬108 !( «¬306 ¨¦§75 «¬319 HIWASSEE «¬315 !( 2 OCOEE H A M II L T O N STATE PARK(!1143 B R A D L E Y Hiwassee WHITWELL !( LAKESITE River !( !( CHESTER HARRISON BAY !( CLEVELAND «¬153 FROST (!15 STATE !( BENTON 14 1 WALDEN PARK 1124 POWELLS CROSSROADS !( PARK «¬ PRENTICE COOPER «¬40 P O L K STATE !( (!16 FOREST Tennessee 15 «¬28 SIGNAL MOUNTAIN 314 River «¬ !13 CHEROKEE BOOKER T. ( 12 «¬123 ¨¦§24 !( RED BANK WASHINGTON NATIONAL STATE PARK FOREST FRANKLIN Tennessee STATE FOREST River CHATTANOOGA ¬313 ¤£411 (! « 16 64 !( JASPER !( Ocoee Lake ¤£ KIMBALL !( COLLEGEDALE «¬156 !( DUCKTOWN Nickajack «¬2 !( RIDGESIDE «¬60 !( «¬74 Lake Ocoee River SOUTH PI!(TTSBURG !( «¬317 !( RED CLAY ORME LOOKOUT!( MOUNTAIN !( EAST RIDGE STATE !( HIST PARK COPPERHILL ¤£72 NEW HOPE «¬134 «¬17 «¬321 South Cumberland State Park Cumberland Trail Cherokee National Forest 1. -

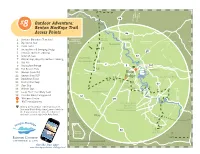

Benton Mackaye Trail Access Points 64

CAROLINA NORTH TENNESSEE ee o c R O i v er 68 # Outdoor Adventure: 18 8 Benton MacKaye Trail Access Points 64 Big Frog Copperhill 1 Springer Mountain (Terminus) TENNESSEE Mountain Big Stamp Gap 2 GEORGIA McCaysville GEORGIA 3 Three Forks 17 4 Toccoa River & Swinging Bridge T spur o c 60 5 Hwy 60, southern crossing 2 c 2 o a S 6 Skeenah Gap F R 60 iv Cohutta e 7 Wilscot Gap, Hwy 60, northern crossing r Wilderness 8 Dial Rd. 16 2 5 515 Shallowford Bridge 9 old 76 Fall Branch Falls Lake 10 FS 64 15 Morganton Blue 11 Weaver Creek Rd. FANNIN COUNTY Blue Ridge 12 Georgia Hwy 515 GILMER COUNTY 13 Ridge A Skeenah Gap Road Boardtown Road s 13 14 k 12 a 14 Bushy Head Gap 11 R Rich oa 60 15 Dyer Gap Mtn d Wilderness 8 FANNIN COUNTY FANNIN 16 Watson Gap 10 6 COUNTY UNION Boardtown Road 7 17 Jacks River Trail (Dally Gap) 9 18 Thunder Rock Campground 52 Welcome Center 515 5 BMT Headquarters 4 Stanley Creek Road To a cco River Old Dial Road Getting to Aska Road: From Highway 515, S u Newport Road turn onto Windy Ridge Road, go one block to r r Doublehead Gap Road the 3 way stop intersection, then turn left o FS u and make a quick right onto Aska Road. n 58 d Ellijay e 3 F Three d S B 4 Forks y 2 F o re st 2 s 52 1 GEORGIA Springer Mountain MAP AREA AT N BMT 10 MILES Get the free App! ©2016 TreasureMaps®.com All rights reserved www.blueridgemountains.com/App.html Fort Loudoun Lake Rockford Lenoir City Mentor E HUNT RD Cherokee National Forest SU Pigeon Forge G D T AR R Watts Bar Lake en L Fort Loudoun Lake Alcoa P Watts Bar Lake n I Y e M 1 ig s B R -

The Wilderness Act of 1964

The Wilderness Act of 1964 Source: US House of Representatives Office of the Law This is the 1964 act that started it all Revision Counsel website at and created the first designated http://uscode.house.gov/download/ascii.shtml wilderness in the US and Nevada. This version, updated January 2, 2006, includes a list of all wilderness designated before that date. The list does not mention designations made by the December 2006 White Pine County bill. -CITE- 16 USC CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM 01/02/2006 -EXPCITE- TITLE 16 - CONSERVATION CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -HEAD- CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -MISC1- Sec. 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of policy; wilderness areas; administration for public use and enjoyment, protection, preservation, and gathering and dissemination of information; provisions for designation as wilderness areas. (b) Management of area included in System; appropriations. (c) "Wilderness" defined. 1132. Extent of System. (a) Designation of wilderness areas; filing of maps and descriptions with Congressional committees; correction of errors; public records; availability of records in regional offices. (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classifications as primitive areas; Presidential recommendations to Congress; approval of Congress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado. (c) Review by Secretary of the Interior of roadless areas of national park system and national wildlife refuges and game ranges and suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; authority of Secretary of the Interior to maintain roadless areas in national park system unaffected. (d) Conditions precedent to administrative recommendations of suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; publication in Federal Register; public hearings; views of State, county, and Federal officials; submission of views to Congress. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 207/Monday, October 26, 2020

67818 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 207 / Monday, October 26, 2020 / Proposed Rules ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION All submissions received must include 1. General Operation and Maintenance AGENCY the Docket ID No. for this rulemaking. 2. Biofouling Management Comments received may be posted 3. Oil Management 40 CFR Part 139 without change to https:// 4. Training and Education B. Discharges Incidental to the Normal [EPA–HQ–OW–2019–0482; FRL–10015–54– www.regulations.gov, including any Operation of a Vessel—Specific OW] personal information provided. For Standards detailed instructions on sending 1. Ballast Tanks RIN 2040–AF92 comments and additional information 2. Bilges on the rulemaking process, see the 3. Boilers Vessel Incidental Discharge National 4. Cathodic Protection Standards of Performance ‘‘General Information’’ heading of the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION section of 5. Chain Lockers 6. Decks AGENCY: Environmental Protection this document. Out of an abundance of 7. Desalination and Purification Systems Agency (EPA). caution for members of the public and 8. Elevator Pits ACTION: Proposed rule. our staff, the EPA Docket Center and 9. Exhaust Gas Emission Control Systems Reading Room are closed to the public, 10. Fire Protection Equipment SUMMARY: The U.S. Environmental with limited exceptions, to reduce the 11. Gas Turbines Protection Agency (EPA) is publishing risk of transmitting COVID–19. Our 12. Graywater Systems for public comment a proposed rule Docket Center staff will continue to 13. Hulls and Associated Niche Areas under the Vessel Incidental Discharge provide remote customer service via 14. Inert Gas Systems Act that would establish national email, phone, and webform. We 15. Motor Gasoline and Compensating standards of performance for marine Systems encourage the public to submit 16. -

Vision for Restoring and Protecting Eastern Forests

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2001 Vision for restoring and protecting Eastern forests Kristen Sykes The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sykes, Kristen, "Vision for restoring and protecting Eastern forests" (2001). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4020. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4020 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ••Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** / Yes, I grant permission )d— No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature: .11 Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 A VISION FOR RESTORING AND PROTECTING EASTERN FORESTS by Kristen Sykes B.A. California State University, Sacramento, 1995 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science The University of Montana May 2001 (^Kair^rsoi^< Dean, Graduate School 5.30-01 Date UMI Number: EP34461 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.