A Survey Mapping the Conflict in Mindanao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo Family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: PHL33460 Country: Philippines Date: 2 July 2008 Keywords: Philippines – Manila – Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide references to any recent, reliable overviews on the treatment of homosexual men in the Philippines, in particular Manila. 2. Do any reports mention the situation for homosexual men in Lanao del Norte? 3. Are there any reports or references to the treatment of homosexual Muslim men in the Philippines (Lanao del Norte or Manila, in particular)? 4. Do any reports refer to Maranao attitudes to homosexuals? 5. The Dimaporo family have a profile as Muslims and community leaders, particularly in Mindanao. Do reports suggest that the family’s profile places expectations on all family members? 6. Are there public references to the Dimaporo’s having a political, property or other profile in Manila? 7. Is the Dimaporo family known to harm political opponents in areas outside Mindanao? 8. Do the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) recruit actively in and around Iligan City and/or Manila? Is there any information regarding their attitudes to homosexuals? 9. -

Quarterly Report

MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Quarterly Report FY 2020 3rd Quarter – April 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020 Submission Date: July 31, 2020 Cooperative Agreement Number: 72049218CA000007 Activity Start Date and End Date: August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 Submitted by: Plan International USA, Inc. This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development Philippine Mission (USAID/Philippines). PROJECT PROFILE USAID/PHILIPPINES Program: MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Activity Start Date and August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 End Date: Name of Prime Plan USA International Inc. Implementing Partner: Cooperative Agreement 72049218CA00007 Number: Names of Ecosystems Work for Essential Benefits (ECOWEB) Subcontractors/Sub Maranao People Development Center, Inc. (MARADECA) awardees: IMPL Project (IMPL) Major Counterpart Organizations Geographic Coverage Lanao del Sur, Marawi City, Lanao del Norte & Iligan City (cities and or countries) Reporting Period: April 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020 2 CONTENTS PROJECT PROFILE .................................................................................................................................... 2 CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................. 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... -

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: a Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: A Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution Jamail A. Kamlian Professor of History at Mindanao State University- ILigan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT), ILigan City, Philippines ABSTRACT Filipina kini menghadapi masalah serius terkait populasi mioniritas agama dan etnis. Bangsa Moro yang merupakan salah satu etnis minoritas telah lama berjuang untuk mendapatkan hak untuk self-determination. Perjuangan mereka dilancarkan dalam berbagai bentuk, mulai dari parlemen hingga perjuangan bersenjata dengan tuntutan otonomi politik atau negara Islam teroisah. Pemberontakan etnis ini telah mengakar dalam sejarah panjang penindasan sejak era kolonial. Jika pemberontakan yang kini masih berlangsung itu tidak segera teratasi, keamanan nasional Filipina dapat dipastikan terancam. Tulisan ini memaparkan latar belakang historis dan demografis gerakan pemisahan diri yang dilancarkan Bangsa Moro. Setelah memahami latar belakang konflik, mekanisme resolusi konflik lantas diajukan dalam tulisan ini. Kata-Kata Kunci: Bangsa Moro, latar belakang sejarah, ekonomi politik, resolusi konflik. The Philippines is now seriously confronted with problems related to their ethnic and religious minority populations. The Bangsamoro (Muslim Filipinos) people, one of these minority groups, have been struggling for their right to self-determination. Their struggle has taken several forms ranging from parliamentary to armed struggle with a major demand of a regional political autonomy or separate Islamic State. The Bangsamoro rebellion is a deep- rooted problem with strong historical underpinnings that can be traced as far back as the colonial era. It has persisted up to the present and may continue to persist as well as threaten the national security of the Republic of the Philippines unless appropriate solutions can be put in place and accepted by the various stakeholders of peace and development. -

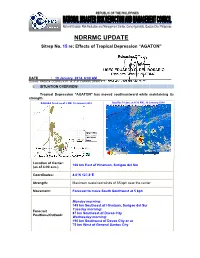

Nd Drrm C Upd Date

NDRRMC UPDATE Sitrep No. 15 re: Effects of Tropical Depression “AGATON” Releasing Officer: USEC EDUARDO D. DEL ROSARIO Executive Director, NDRRMC DATE : 19 January 2014, 6:00 AM Sources: PAGASA, OCDRCs V,VII, IX, X, XI, CARAGA, DPWH, PCG, MIAA, AFP, PRC, DOH and DSWD I. SITUATION OVERVIEW: Tropical Depression "AGATON" has moved southeastward while maintaining its strength. PAGASA Track as of 2 AM, 19 January 2014 Satellite Picture at 4:32 AM., 19 January 2014 Location of Center: 166 km East of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur (as of 4:00 a.m.) Coordinates: 8.0°N 127.8°E Strength: Maximum sustained winds of 55 kph near the center Movement: Forecast to move South Southwest at 5 kph Monday morninng: 145 km Southeast of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur Tuesday morninng: Forecast 87 km Southeast of Davao City Positions/Outlook: Wednesday morning: 190 km Southwest of Davao City or at 75 km West of General Santos City Areas Having Public Storm Warning Signal PSWS # Mindanao Signal No. 1 Surigao del Norte (30-60 kph winds may be expected in at Siargao Is. least 36 hours) Surigao del Sur Dinagat Province Agusan del Norte Agusan del Sur Davao Oriental Compostela Valley Estimated rainfall amount is from 5 - 15 mm per hour (moderate - heavy) within the 300 km diameter of the Tropical Depression Tropical Depression "AGATON" will bring moderate to occasionally heavy rains and thunderstorms over Visayas Sea travel is risky over the seaboards of Luzon and Visayas. The public and the disaster risk reduction and management councils concerned are advised to take appropriate actions II. -

Quarterly Report

MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Quarterly Report FY 2020 1st Quarter – October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 Submission Date: January 31, 2020 Cooperative Agreement Number: 72049218CA00007 Activity Start Date and End Date: August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 Submitted by: Plan International USA, Inc. This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development Philippine Mission (USAID/Philippines). 1 PROJECT PROFILE Program: USAID/PHILIPPINES MARAWI RESPONSE PROJECT (MRP) Activity Start Date and End August 29, 2018 – August 28, 2021 Date: Name of Prime Plan USA International Inc. Implementing Partner: Cooperative Agreement 72049218CA00007 Number: Names of Subcontractors/ Ecosystems Work for Essential Benefits (ECOWEB) and Sub-awardees: Maranao People Development Center, Inc. (MARADECA) Major Counterpart Organizations Geographic Coverage Lanao del Sur, Marawi City, Lanao del Norte and Iligan City (cities and or countries) Reporting Period: October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 2 CONTENTS PROJECT PROFILE .......................................................................................................... 2 CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................... 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 5 2. PROJECT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. -

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

4. Resources, Security and Livelihood

Violent Conflicts and Displacement in Central Mindanao 4. RESOURCES, SECURITY AND LIVELIHOOD This section examines households’ perceptions of their surrounding environment (e.g. security). It looks at their resources or capital (social, natural, economic) available to households, as well as how those resources were being used to shape livelihood strategies and livelihood outcomes such as food security. The results give insights into the complex interaction between, on the one hand, displacement and settlement options, and, on the other hand, access to basic needs, services and livelihood strategies. Services and Social Relations Access to Services Across the study strata, about one-third of the households ranked their access to services negatively, including access to education (22%), access to (35%) and quality of (32%) health care, and access to roads (37%). Respondents in Maguindanao ranked on average all services more negatively than any other strata. Disaggregated by settlement status, respondents who were displaced at the time of the survey were more likely to rank services negatively compared to others, with the exception of access to roads. Nearly the same percentage of households who were displaced at the time of survey and those returned home found the road to be bad of very bad (47% and 55%, respectively). Figure 11: Ranking of services (% bad - very bad) Two-thirds (67%) of the sampled households had children aged 6-12 years, and among them nearly all had children enrolled in primary school (97%). However, 36 percent of the households reported that their school-enrolled children missed school for at least a week within the 6 months prior to the survey. -

The Regional Development Report Scorecard Xix Joint RDC IX and RPOC IX Resolution Xxi Foreword Xxiii Message Xxiv Executive Summary Xxv

Zamboanga Peninsula 2019Regional Development Report Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations iii List of Tables and Figures xi The Regional Development Report Scorecard xix Joint RDC IX and RPOC IX Resolution xxi Foreword xxiii Message xxiv Executive Summary xxv Chapter 02 Global and Regional Trends and Prospects 1 Chapter 03 Overlay of Economic Growth, Demographic Trends and 5 Physical Characteristics Chapter 04 Zamboanga Peninsula Regional Development Plan 2017-2022 9 Overall Framework Chapter 05 Ensuring People-Centered, Clean and Efficient Governance 13 Chapter 06 Pursuing Swift and Fair Administration of Justice 21 Chapter 07 Promoting Philippine Culture and Values 29 Chapter 08 Expanding Economic Opportunities in Agriculture, Forestry, 33 and Fisheries Chapter 09 Expanding Economic Opportunities in Industry and Services 49 through Trabaho at Negosyo Chapter 10 Accelerating Human Capital Development 57 Chapter 11 Reducing Vulnerability of Individuals and Families 67 Chapter 12 Building Safe and Secure Communities 71 Chapter 13 Reaching for the Demographic Dividend 75 Chapter 14 Vigorously Advancing Science, Technology and Innovation 79 Chapter 15 Ensuring Sound Macroeconomic Policy 85 Chapter 17 Attaining Just and Lasting Peace 95 Chapter 18 Ensuring Security, Public Order and Safety 105 Chapter 19 Accelerating Infrastructure Development 117 Chapter 20 Ensuring Ecological Integrity, Clean and Healthy 133 Environment Chapter 22 Plan Implementation and Monitoring 145 Glossary of Terms 153 2019 Zamboanga Peninsula Regional Development -

DSWD DROMIC Report #1 on the Armed Conflict in Lanao Del Sur As of 22 June 2018, 1AM

DSWD DROMIC Report #1 on the Armed Conflict in Lanao del Sur as of 22 June 2018, 1AM SUMMARY On 16 June 2018, at around 10:00PM, Armed conflict incident transpired in Tubaran, Lanao del Sur B between the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and alleged “ISIS group. This resulted in the massive evacuation of affected families. 1. Status of Affected Families/ Persons 3,121 families or 14,873 persons were affected by the armed conflict (see Table 1). Table 1. Affected Families/ Persons NUMBER OF AFFECTED REGION / PROVINCE / MUNICIPALITY Barangays Families Persons GRAND TOTAL 19 3,121 14,873 ARMM 19 3,121 14,873 Lanao del Sur B 19 3,121 14,873 Tubaran 10 1,816 8,614 Pagayawan 7 1,258 6,134 Calanugas 1 15 45 Marogong 1 32 80 Source: DSWD-Field Office XII 2. Status of Displaced Families/Individuals Inside Evacuation Center 739 families or 3,532 persons are currently staying in 17 evacuation centers (see Table 2). Table 2. Displaced Families / Persons Inside Evacuation Centers NUMBER OF NUMBER OF SERVED EVACUATION INSIDE ECs REGION / PROVINCE / CENTERS MUNICIPALITY (ECs) Families Persons CUM NOW CUM NOW CUM NOW GRAND TOTAL 17 17 739 739 3,532 3,532 ARMM 17 17 739 739 3,532 3,532 Lanao del Sur B 17 17 739 739 3,532 3,532 Tubaran 4 4 439 439 2,200 2,200 Pagayawan 5 5 117 117 615 615 Binidayan 3 3 74 74 378 378 Page 1 of 3|DSWD DROMIC Report #1 on the Armed Conflict in Lanao del Sur as of June 22, 2018, 1AM NUMBER OF NUMBER OF SERVED EVACUATION INSIDE ECs REGION / PROVINCE / CENTERS MUNICIPALITY (ECs) Families Persons CUM NOW CUM NOW CUM NOW Ganassi 4 4 98 98 283 283 Madamba 1 1 11 11 56 56 Source: DSWD-Field Office XII Outside Evacuation Center 2,382 families or 11,341 persons are temporarily staying with relatives (see Table 3). -

Agusan Del Norte

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Parel, Danileen Kristel C.; Detros, Keith C.; Salinas, Christine Ma. Grace R. Working Paper Bottom-up Budgeting Process Assessment: Agusan del Norte PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2015-26 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Parel, Danileen Kristel C.; Detros, Keith C.; Salinas, Christine Ma. Grace R. (2015) : Bottom-up Budgeting Process Assessment: Agusan del Norte, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2015-26, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127035 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Bottom-up Budgeting Process Assessment: Agusan del Norte Danileen Kristel C. -

Application for the Approval of the Renewable Energy Supply Agreement Between Zamboanga Del Sur I Electric Cooperative, Inc

Oc1cT 16 APR 26 P4 :40 REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSJtJNDnv: —. — SAN MIGUEL AVENUE, PASIG CITY IN THE MAflER OF THE APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF THE RENEWABLE ENERGY SUPPLY AGREEMENT BETWEEN ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR I ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (ZAMSURECO I) AND ASTRONERGY DEVELOPMENT PAGADIAN, INC. (ASTRONERGY), WITH PRAYER FOR THE ISSUANCE OF PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY, ERC Case No. 2016- 0-c'2RC ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR I ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (ZAMSURECO I) AND ASTRONERGY DEVELOPMENT PAGADIAN INC. (ASTRONERGY), Applicants. APPLICATION WITH MOTION FOR CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT OF INFORMATION AND PRAYER FOR ISSUANCE OF PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY Joint Applicants, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR I ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (ZAMSURECO I) and ASTRONERGY DEVELOPMENT PAGADIAN INC. (ASTRONERGY) through counsel, unto this Honorable Commission1 respectfully allege, that: ljPage THE APPLICANTS 1. ZAMSURECO I is a non-stock, non-profit electric cooperative, organized and existing by virtue of Presidential Decree No. 269, as amended, with principal office at Gov. Vicente M. Cerilles St., Pagadian City, Zamboanga del Sur. It is engaged in the distribution of electric light and power within its service area which covers the City of Pagadian and certain municipalities of the province of Zamboanga Del Sin, namely: Aurora, Dimataling, Dinas, Dumalinao, Dumingag,Guipos,1Labangan, Lapuyan, Mahayag, Margosatubig, Midsalip, Molave, R. Magsaysay, San Miguel, San Pablo, Tabina,Tambulig, Tigbao, 2Tukuran, Sominot (formerly Don Mariano Marcos), 3Pitogo, Josefina and Vincenzo Sagun, and the municipality of Don Victoriano in the province of Misamis Occidental4 . Copies of ZAMSURECO I's Articles of Incorporation and By-Laws, Certificate of Franchise, NEA Certificate of Registration and latest Audited Financial Statements are attached hereto and made integral parts hereof as Annexes "A", "B", "C", "D" and "E", respectively.