Download (1674Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News from and About Members

News from and about Members Rutland 2013-14 After my Declaration ceremony on 12 April 2013 I realised the relevance of the motto of Rutland, Multum in Parvo, adopted by the County Council in 1950. Rutland has the smallest population of any unitary authority in mainland England, but I have been kept extremely busy.The preparation given at the Burghley seminars and the regional conferences was thorough and extremely useful and I recommend them wholeheartedly to any High Sheriff in nomination. My main aim was to maintain the historic role of this ancient office, but at the same time to make people aware of its presence in modern society. During the year I was responsible for organising the very significant Biennial My High Sheriff’s Awards with the historic backdrop of the horseshoes at Oakham Castle Justice Service and Court Sitting which Left to right: Mount Group Riding for the Disabled; Angela Humphreys, a volunteer almost takes place in Rutland, to keep everywhere I went; Staff Sergeant Instructor Georgina Crosby; Margaret Demaine, Oakham Castle as the longest-running Dementia Friends; Paul Beech, volunteer at Warning Zone; seat of justice for over 850 years. It was Rob Persani of Rutland Radio. a day to remember with wonderful Before my Declaration ceremony, I had Warning Zone has been a significant support from all the neighbouring High been approached to organise the East focus for me this year and I have visited Sheriffs in the East Midlands Region. Midlands regional conference, which it with nearly every Year 6 at school in was a challenge for me as a new High Rutland.This charity very much In Rutland we do not have regular Sheriff, but the support I received from involves the important historic role of court sittings, a cathedral or a university the Association was excellent. -

Lordship of Kettlethorpe Hall

Lordship of Kettlethorpe Hall Ketton Principal Victoria County Parish/ County Rutland Source Histories Date History of Lordship Monarchs 871 Creation of the English Monarchy Alfred the Great 871-899 Edward Elder 899-924 Athelstan 924-939 Edmund I 939-946 Edred 946-955 Edwy 955-959 Edgar 959-975 Edward the Martyr 975-978 Ethelred 978-1016 Edmund II 1016 Canute 1016-1035 Harold I 1035-1040 Harthacnut 1040-1042 Edward the Confessor 1042-1066 Harold II 1066 1066 Norman Conquest- Battle of Hastings William I 1066-1087 1086 Domesday William II 1087-1100 Henry I 1100-35 Stephen 1135-54 Henry II 1154-89 Richard I 1189-99 1215 Magna Carta John 1199-1216 1215-1217 First Barons War Henry III 1216-72 1264-1267 Second Barons War 1301 Robert Luterel is licenced to grant lands (a manor) in Ketton to Edward I 1272-1307 the Priory of Sempringham, Lincolnshire. Edward II 1307-27 1342 Hasculph de Whitwell adds (a manor or grange) to the Priory’s Edward III 1327-77 lands with the direction that the income be devoted to the maintenance of a chaplain. Richard II 1377-1399 Henry IV 1399-1413 Henry V 1413-22 1455-1487 War of the Roses Henry VI 1422-61 1470-71 Edward IV 1461-70 1471-83 Edward V 1483 Richard III 1483-5 © Copyright Manorial Counsel Limited 2014 Lordship of Kettlethorpe Hall Date History of Lordship Monarchs Henry VII 1485-1509 1534 The Act of Supremacy – Church of England Henry VIII 1509-47 The Priory is dissolved, and the two manors are taken by the Crown. -

Doing It Differently

RUTLAND News from and about members Doing it differently THE BBC described Friday 13 March 2020 as ‘The weekend the world changed’; for me it was the day I gave up work to focus on the year ahead. I had been advised that it is not about ‘being High Sheriff’ but ‘doing High Sheriff’; 2020-21 was about doing it differently. We quickly rearranged my Declaration from Oakham Castle to its car park with just the handful of essential people attending and witnessed by a confused dog walker. The following week the Rutland Times headline stated ‘I will be a virtual High Sheriff’. I had no idea what that meant but soon went to places I had never been before – Twitter and Instagram. As lockdown took hold, letter-writing, Stocken Prison Hidden Heroes Day with Lord-Lieutenant, Prison Governor Neil Thomas and High Sheriff’s Cadet Bradie Smith emails and Zoom replaced planned visits as I realised that flexibility is everything. The East Midlands High Sheriff team met regularly over Skype which was invaluable for sharing ideas and maintaining morale! As High Sheriff during the COVID-19 crisis it was vital to be a ‘glass half full person’ and make the most of what you could do. A key part of the role is to work closely with the Lord-Lieutenant; Dr Sarah Furness and I wrote to every town and Presenting a ‘How the Police keep me safe’ Completing the Rutland Round walk with Nick parish council seeking nominees to receive poster competition winner’s certificate to Alfie Clarke on market day in Uppingham greeted letters of thanks for the help they had with PC Joe Lloyd by Deputy Mayor Liz Clarke given others to cope with the challenges of COVID. -

Rutland Record No. 19

No 19 (1999) Journal of the Rutland Local History & Record "Society Rutland cal isto ecord ciety The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology and History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in an aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700273 PRESIDENT Prince Yuri Galitzine CHAIRMAN J Field VICE-CHAIRMEN P N Lane HONORARY SECRETARY P Rayner, c/o Rutland County Museum, Oakham, Rutland HONORARY TREASURER Dr M Tillbrook, 7 Redland Road, Oakham, Rutland HONORARY MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Mrs E Clinton, c/o Rutland County Museum, Oakham, Rutland HONORARY EDITOR T H McK Clough HONORARY ARCHIVIST C Harrison, Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester & Rutland HONORARY LEGAL ADVISER J B Ervin EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The Officers of the Society and the following elected members: M E Baines, D Carlin, Mrs S Howlett, Mrs E L Jones, Professor A Rogers, D Thompson EDITORIAL COMMITTEE ME Baines, TH McK Clough (convenor), J Field, Prince Yuri Galitzine, R P Jenkins, P N Lane, Dr M Tillbrook HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE D Carlin ARCHAEOLOGICAL COMMITTEE Chairman: Mrs EL Jones HONORARY MEMBERS Sqn Ldr A W Adams, Mrs O Adams, Miss E B Dean, B Waites Enquiries relating to the Society's activities, such as membership, editorial matters, historic buildings, or programme of events, should be addressed to the appropriate Officer of the Society. -

The Traditional Touch ALSO INSIDE: ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2019 WINTER 2019 ANTONIA PUGH-THOMAS

The traditional touch ALSO INSIDE: ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2019 WINTER 2019 ANTONIA PUGH-THOMAS Haute Couture Shrieval Outfits for Lady High Sheriffs 0207731 7582 659 Fulham Road London, SW6 5PY www.antoniapugh-thomas.co.uk Volume 38 Issue 2 Winter 2019 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL Officers and Council November 08 14 2019 to November 2020 OFFICERS Chairman The Hon H J H Tollemache Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary 21 32 J H A Williams Esq MBE Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory Esq DL Thorpland Hall, Fakenham Norfolk NR21 0HD Tel 01328 862392 Email [email protected] COUNCIL Canon S E A Bowie DL T H Birch Reynardson Esq D C F Jones Esq DL J A T Lee Esq OBE Mrs V A Lloyd DL Mrs A J Parker JP DL Dr R Shah MBE JP DL Lt Col A S Tuggey CBE DL W A A Wells Esq TD (Hon Editor of The High Sheriff ) S J Young Esq MC JP DL The High Sheriff is published twice a year by Hall-McCartney Ltd for the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales Hon Editor Andrew Wells Email [email protected] ISSN 1477-8548 ©2019 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales 4 From the Editor 13 Recent Events – 42 High Sheriffs The Association is not as a body of England and Wales responsible for the opinions expressed Lady High Sheriffs in The High Sheriff unless it is stated Diary 2019-20; new members; that an article or a letter officially 5 represents the Council’s views. -

Parish Priest's Postscript, February 2017. 1. the High Sheriff of Rutland

Parish Priest’s Postscript, February 2017. 1. The High Sheriff of Rutland, Dr. Sarah Furness has invited all the parishes in the region to a big service in Peterborough Cathedral on 26 February at 3.30pm. As she comes towards the end of her Shrivel Year, Dr. Furness, in the company of The Lord Lieutenant, has also invited a real sheriff to attend: The Rutland Sheriff from Vermont USA complete with his uniform – though horse will be optional! I do hope a number of people from the Benefice will give their support to this service partly because the next High Sheriff of Rutland is actually living in the Benefice: Craig Mitchell from Barrowden. To support this event will also help us to understand what Craig Mitchell’s appointment will signify. There will be a party afterwards with much cake so please email [email protected] to inform the authorities how many people will be travelling in your car. 2. The Welland-Fosse Benefice now has a website! It contains information about our five parishes; news of forthcoming events, services rotas and – if you have the stomach for it – old sermons! It is free to use but it an enormous leap forward in communication terms to enable the whole world to know of our existence and the quality of life which we enjoy. My primary concern is not the whole world but the communication with you and the rest of the benefice which is, of its very nature, complicated and sometimes dismally slow. Please use it! We need your email address so that you can receive immediate news via the website. -

J\S-Aacj\ Cwton "Wallop., $ Bl Sari Of1{Ports Matd/I

:>- S' Ui-cfAarria, .tffzatirU&r- J\s-aacj\ cwton "Wallop., $ bL Sari of1 {Ports matd/i y^CiJixtkcr- ph JC. THE WALLOP FAMILY y4nd Their Ancestry By VERNON JAMES WATNEY nATF MICROFILMED iTEld #_fe - PROJECT and G. S ROLL * CALL # Kjyb&iDey- , ' VOL. 1 WALLOP — COLE 1/7 OXFORD PRINTED BY JOHN JOHNSON Printer to the University 1928 GENEALOGirA! DEPARTMENT CHURCH ••.;••• P-. .go CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Omnes, si ad originem primam revocantur, a dis sunt. SENECA, Epist. xliv. One hundred copies of this work have been printed. PREFACE '•"^AN these bones live ? . and the breath came into them, and they ^-^ lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.' The question, that was asked in Ezekiel's vision, seems to have been answered satisfactorily ; but it is no easy matter to breathe life into the dry bones of more than a thousand pedigrees : for not many of us are interested in the genealogies of others ; though indeed to those few such an interest is a living thing. Several of the following pedigrees are to be found among the most ancient of authenticated genealogical records : almost all of them have been derived from accepted and standard works ; and the most modern authorities have been consulted ; while many pedigrees, that seemed to be doubtful, have been omitted. Their special interest is to be found in the fact that (with the exception of some of those whose names are recorded in the Wallop pedigree, including Sir John Wallop, K.G., who ' walloped' the French in 1515) every person, whose lineage is shown, is a direct (not a collateral) ancestor of a family, whose continuous descent can be traced since the thirteenth century, and whose name is identical with that part of England in which its members have held land for more than seven hundred and fifty years. -

To Rutland Record 21-30

Rutland Record Index of numbers 21-30 Compiled by Robert Ovens Rutland Local History & Record Society The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology & History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in all aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700723 The main contents of Rutland Record 21-30 are listed below. Each issue apart from RR25 also contains annual reports from local societies, museums, record offices and archaeological organisations as well as an Editorial. For details of the Society’s other publications and how to order, please see inside the back cover. Rutland Record 21 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 31 9 Letters of Mary Barker (1655-79); A Rutland association for Anton Kammel; Uppingham by the Sea – Excursion to Borth 1875-77; Rutland Record 22 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 32 7 Obituary – Prince Yuri Galitzine; Returns of Rutland Registration Districts to 1851 Religious Census; Churchyard at Exton Rutland Record 23 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 33 4 Hoard of Roman coins from Tinwell; Medieval Park of Ridlington;* Major-General Lord Ranksborough (1852-1921); Rutland churches in the Notitia Parochialis 1705; John Strecche, Prior of Brooke 1407-25 -

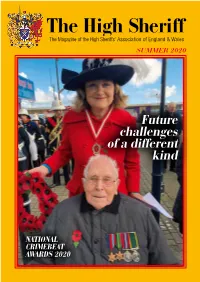

Future Challenges of a Different Kind

SUMMER 2020 Future challenges of a different kind NATIONAL CRIMEBEAT AWARDS 2020 www Lady Shrieval .antoniapugh-thom High Ant Haute dr ess Sheriffs onia for Coutur Pugh- as.co.uk eW omensw Thomas 020 ear 7731 7582 Photo courtesy of Harald Altmaier Volume 39 Issue 1 Summer 2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL 12 15 Officers and Council 2020 OFFICERS Chairman The Hon H J H Tollemache Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary 34 38 J H A Williams Esq MBE Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory Esq DL Thorpland Hall, Fakenham Norfolk NR21 0HD Tel 01328 862392 Email [email protected] COUNCIL Canon S E A Bowie DL T H Birch Reynardson Esq D C F Jones Esq DL J A T Lee Esq OBE DL Mrs V A Lloyd DL Mrs A J Parker JP DL Dr R Shah MBE JP DL Lt Col A S Tuggey CBE DL W A A Wells Esq TD (Hon Editor of The High Sheriff ) S J Young Esq MC JP DL The High Sheriff is published twice a year by Hall-McCartney Ltd for the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales Hon Editor Andrew Wells Email [email protected] ISSN 1477-8548 ©2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales 4 From the Editor 12 General Election 44 Association regalia The Association is not as a body responsible for the opinions expressed and publications in The High Sheriff unless it is stated The ‘Red Mass’ that an article or a letter officially Diary 15 represents the Council’s views. -

The Rutland Record Index for Records 11

rutland record index COVER:Layout 1 13/10/2011 14:27 Page 1 Rutland Record Journal of the Rutland Local History & Record Society Index of numbers 11-20 Compiled by Robert Ovens rutland record index COVER:Layout 1 13/10/2011 14:27 Page 2 RutlandRutland Local Local History History & & Record Record Society Society The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology & History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in all aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700723 These are the main contents of Rutland Record 11-20. Each issue also contains annual reports from local societies, museums, record offices and archaeological organisations. For details of the Society’s other publications and how to order, please see inside the back cover. Rutland Record 11 (OP) ISBN 978 0 907464 16 7 Rutland, Russia and Shakespeare; A medieval bishop in Rutland; Industrial archaeology in Rutland; The fifth Earl of Lonsdale in the Arctic; The survival of elms in Rutland Rutland Record 12 (£2.00, members £1.50) ISBN 978 0 907464 17 4 Flitteris and Cold Overton: two medieval deer parks; A village archive: Preston parish records; The great educational experiment: Edward Thring at Uppingham School; Jeremiah Whittaker: a turbulent -

Ellis Wasson the British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 1

Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 1 Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 1 Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński ISBN 978-3-11-054836-5 e-ISBN 978-3-11-054837-2 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2017 Ellis Wasson Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Thinkstock/bwzenith Contents Acknowledgements XIII Preface XIV The Entries XV Abbreviations XVII Introduction 1 List of Parliamentary Families 5 Dedicated to the memory of my parents Acknowledgements A full list of those who helped make my research possible can be found in Born to Rule. I remain deeply in debt to the inspiration and mentorship of David Spring. Preface In this list cadet, associated, and stem families are arranged in a single entry when substantial property passed between one and the other providing continuity of parliamentary representation (even, as was the case in a few instances, when no blood or marriage relationship existed). Subsidiary/cadet families are usually grouped under the oldest, richest, or most influential stem family. Female MPs are counted with their birth families, or, if not born into a parliamentary family, with their husband’s family. -

Descendants of John Hanbury

Descendants of John Hanbury Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of John Hanbury 1-John Hanbury John married someone. He had three children: Edward, (No Given Name), and Richard. 2-(Is This John's Son?) Edward Hanbury Edward married someone. He had one son: Humphrey. 3-Humphrey Hanbury, son of (Is This John's Son?) Edward Hanbury, died in 1501 in Hanbury, Worcestershire. Humphrey married someone. He had one son: Anthony. 4-Anthony Hanbury Anthony married Anne Jennettes. They had one son: Walter. 5-Walter Hanbury1 died in 1590. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as an Of Beanhall, Worcester. Walter married Cicley Rous, daughter of John Rous and Ann Montagu. They had one son: John. 6-Sir John Hanbury John married Mary Whethill. They had two children: Edward and Mary. 7-Edward Hanbury1 died in 1656. Noted events in his life were: • He had a residence in Kelmarsh, Northamptonshire. Edward married Lucy Martin. Edward next married Mary Shuckburgh, daughter of Edward Shuckburgh. They had one son: John. 8-John Hanbury John married Mary Waller, daughter of Thomas Waller. They had two children: John and Thomas. 9-John Hanbury John married Catherine Gore, daughter of Sir William Gore. They had one daughter: Elizabeth. 10-Elizabeth Hanbury died on 9 Jan 1799. Elizabeth married Jacob Bosanquet1 on 18 Jan 1748. Jacob was born on 22 Dec 1713 and died on 9 Jun 1767 at age 53. They had one son: William. Noted events in his life were: • He had a residence in London. 11-William Bosanquet1 was born on 4 Jul 1757 and died on 21 Jun 1800 at age 42.