Pappu Venugopala Rao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

2006-Journal 13Th Issue

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2006 Thirteenth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA September 2006, Thirteenth Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. R.Nagaswami Dr.T.K.Venkatasubramaniam Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. T.K. Venkatasubramaniam Prof. Vijaya Ramaswamy Dr. A. Satyanarayana Published by C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org Subscription Rs.95/- (for 2 issues) Rs.180/-(for 4 issues) 2 September 2006, Thirteenth Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS ANCIENT HISTORY Bhima Deula : The Earliest Structure on the Summit of Mahendragiri - Some Reflections 9 Dr. R.C. Misro & B.Subudhi The Contribution of South India to Sanskrit Studies in Asia - A Case Study of Atula’s Mushikavamsa Mahakavya 16 T.P. Sankaran Kutty Nair The Horse and the Indus Saravati Civilization 33 Michel Danino Gender Aspects in Pallankuli in Tamilnadu 60 Dr. V. Balambal Ancient Indian and Pre-Columbian Native American Peception of the Earth ( Mythology, Iconography and Ritual Aspects) 80 Jayalakshmi Yegnaswamy MEDIEVAL HISTORY Antiquity of Documents in Karnataka and their Preservation Procedures 91 Dr. K.G. Vasantha Madhava Trade and Urbanisation in the Palar Valley during the Chola Period - A.D.900 - 1300 A.D. -

SRUTI-India Carnatic Music,India Dance & Music Magazine

SRUTI-India Carnatic Music,india dance & music magazine Internet Edition February & March 2001 India's premier music and dance magazine Home Editor's Note News & Notes (Continued) Spotlight Reproduced from Sruti 197 (February 2001). Brief Notes HOMAGE TO MAX MUELLER IN CHENNAI Main Feature PRESENTATIONS OF MUSIC, DANCE & DRAMA Back o' & Feedback Form Max Mueller Bhavan (German Cultural Institute) in Chennai organised a clutch of Sruti - Issue 197 cultural programmes and a seminar during 28-30 November 2000 to mark the death February 2001 centenary of Max Mueller, a great Indologist. Born in 1823, Mueller died when he was 77. Mueller is remembered for stimulating widespread interest in Indology, mythology, philosophy, comparative religion, linguistics and social criticism. The special cultural relations between India and Germany are largely attributed to his works. Mueller never visited India. But, had he come to India, he would likely have sought the company of musicians and scholars in the field of the performing arts, considering that he wanted to become a musician and belonged to a family that considered music and poetry a way of life. His first love was indeed music which he would have taken up as a profession but for the unfavourable climate for such a pursuit in his days. The famous Indologist is best known all over the world for the publication of the Sacred Books of the East (51 volumes), amongst several other works. He was an ardent promoter of Indian independence and cultural self-assertion. Max Mueller Bhavan, Chennai, entrusted Ludwig Pesch, a German who has spent years learning and studying Carnatic music, with the task of planning a befitting programme of tribute in Chennai in the wider context of a major German festival under way in India. -

“I Cannot Live Without Music”

INTERVIEW “I cannot live without music” Swati Tirunal was undoubtedly one of the most important modern composers, one who included Hindustani styles in his compositions. Nowadays it has become fashionable to say you must avoid Hindustani in Carnatic music or the other way around. But looking back, Bhimsen Joshi was among those south Indians who became luminaries in the north Indian style. How many south Indians are really open to Hindustani music is debatable. The late M.S. Gopalakrishnan was very competent in the Hindustani field, and my colleague Sanjay Subrahmanyan is a Carnatic musician open to Hindustani ragas – he sings a Rama Varma at the Swarasadhana workshop focussing on Swati Tirunal’s compositions pallavi in Bagesree, for instance. Then again there are ‘fundamentalist’ groups Well known Carnatic vocalist Rama Varma was in Chennai recently to who think Behag, Sindhubhairavi, conduct a two-day workshop (9 and 10 February 2013) Swarasadhana, Yamunakalyani, Sivaranjani and their at the Satyananda Yoga Centre at Triplicane. Here he speaks of the event, ilk should be totally done away with. his journey in classical music and his thoughts on the changing trends of the art form. Rama Varma How did Swarasadhana happen? in conversation with I have been teaching in a village called Perla near Mangalore for the past M. Ramakrishnan four years, at a music school called Veenavadini, run by the musician Yogeesh Sharma. He invites musicians to visit there once a year. Four years ago Veenavadini invited me. They enjoyed my teaching and Do you follow the same style of teaching I enjoyed being there too, and my visits became regular. -

Sample Quizzes

SAMPLE QUIZZES Two quizzes follow, each of them representing different topics of information to be acquired by students, who are themselves at different levels of learning. They are only a sampler of what might be developed as an assessment of student learning of the musical culture of Bulgaria. Quiz 1. Multiple Choice. Choose the best or most appropriate answer. 1. In the medieval period of Indian music (12th through 17th centuries), painters were commission to paint sets of miniature paintings of entire rag (or raga) families, called (a) rāginis, (b) rāgamālas, (c) rāgamālikas, (d) Bhairagi. 2. The old vocal music form consisting of a slow abstract beginning which gathers momentum, “restarts” with a fixed composition, and climaxes with a fast rhythmic section, and which has influenced most later North Indian classical forms, is known as (a) dhrupad, (b) khyāl, (c) jor, (d) alāap. 3. Syllables that are used by musicians to construct rhythmic patterns (such as “taka”, “takita”, and “takadimi”) are known as (a) talās, (b) lāyas, (c) chhands, and (d) jātīs. 4. Syllables for pitches in a scale are sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni-sa, known collectively as (a) sruti, (b) sārgām, (c) gintī, (d) rāga. 1. The oldest scriptures in India, dating from 1500 BCE and comprised of sacred hymns, poetic descriptions of the gods and nature, rituals, and blessings, are known as the (a) Bharatā Natyam, (b) Vedas, (c) Vikritis, (d) Mantrās. 2. Which of the following is not a general quality common to all ragas? (a) A rāga must have at least five notes and cannot omit Sa, (b) There is an ascending and descending format, (c) Some form of Re must be present, (d) Certain moods are associated with each. -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

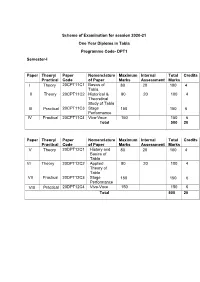

Scheme of Examination for Session 2020-21 One Year Diploma in Tabla Programme Code- DPT1 Semester-I Paper Theory/ Practical

Scheme of Examination for session 2020-21 One Year Diploma in Tabla Programme Code- DPT1 Semester-I Paper Theory/ Paper Nomenclature Maximum Internal Total Credits Practical Code of Paper Marks Assessment Marks I Theory 20CPT11C1 Basics of 80 20 100 4 Tabla II Theory 20CPT11C2 Historical & 80 20 100 4 Theoretical Study of Tabla III Practical 20CPT11C3 Stage 150 150 6 Performance IV Practical 20CPT11C4 Viva-Voce 150 150 6 Total 500 20 Paper Theory/ Paper Nomenclature Maximum Internal Total Credits Practical Code of Paper Marks Assessment Marks V Theory 20DPT12C1 History and 80 20 100 4 Basics of Tabla VI Theory 20DPT12C2 Applied 80 20 100 4 Theory of Tabla VII Practical 20DPT12C3 Stage 150 150 6 Performance VIII Practical 20DPT12C4 Viva-Voce 150 150 6 Total 500 20 The candidate has to answer five questions by selecting atleast one question from each Unit. Maximum Marks 80 Internal Assessment 20 marks Semester 1 Theory Paper - I Programme Name One Year Diploma Programme Code DPT1 in Tabla Course Name Basics of Tabla Course Code 20CPT11C1 Credits 4 No. of 4 Hours/Week Duration of End 3 Hours Max. Marks 100 term Examination Course Objectives:- 1. To impart Practical knowledge about Tabla. 2. To impart knowledge about theoretical aspects of Tabla in Indian Music. 3. To impart knowledge about Tabla and specifications of Taala 4. To impart knowledge about historical development of Tabal and it’s varnas(Bols) Course Outcomes 1. Students would able to know specifications of Tabla and Taalas 2. Students would gain knowledge about Historical development of Tabla 3. -

Warhammer Vermintide 2 Beta

Warhammer vermintide 2 beta Continue Trying to figure out the best 10 books Malayalam has ever had, through Goodreads. The book's overall score is based on several factors, including the number of people who voted for it, and how highly these voters rated the book. You must have account goodreads to vote. To vote on the existing books from the list, next to each book there is a link to vote for this book clicking it will add this book to their votes. To vote for a book not on the list or books that you couldn't find on the list, you can click on the tab to add books to that list and then choose from your books, or just search. Shown 1-50 of 68 Gaumukh Yatra Unknown Count : 2279 File size : 1.11 MB India Charithravalokam Panikkar Read Count : 1586 File size : 53.98 MB Simhabhoomi Pottekkatt Read Count : 1586 File size : 20.04 MB Uma Vivaham Unknown Count : 880 File size : 8.39 MB Sringara Tilakam Kalidasaki Prani Kalidhasan Read Count : 504 File size : 3.3 MB Vemana Kumaar Rabindra Read Count : 997 File size : 2.43 MB Mangalodhayam Book-8 Ramawarma Apam Tabburan Read Count : 858 File size : 69.7 MB Katya Panjab Unknown Count : 1154 File size : 4.02 MB Copyright © 2020, Matrubharti Technologies Pvt. LLC All rights reserved. 580,893 581K Sreyas Spiritual E-Books PDF - - Collection of Spiritual E-Books (PDF File) in Malayalam, Digitized by the Sreyas Foundation, on www.sreyas.in favoritefavoritefavoritefavoritefavorite (1 reviews) Topics: Sreyas, Malayalam, Spiritual Pt.1. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

List of Kathakali Videos (Complimentary Copies Available Only for Members of Drisyavedi)

List of Kathakali Videos (Complimentary copies available only for members of Drisyavedi) Sl.No. DVD No. Story/Artistes Total DVDs 001 009 Padakatchery 24-07-06 2 Kala. Sankaran Embranthiri/Meledam Narayanan Namputhiri Krishnadas/Ratnakaran 002 010 Ravanavijayam 01-08-06 1 Madavoor Vasudevan Nair/Kala. Rajasekharan/ Kal. Ravikumar/Thiruvalla Gopikuttan/Kal. Krishnankutty/ Kuroor Vasudevan Namputhiri/Kalanilayam Manoj 003 020 Nizhalkutth 11-09-06 2 Inchakattu Ramachandran Pillai/Attingal Peethambaran Margi: Balasubramanyam/Suresh/Murali/Chavara Parukutty/ Kala. Shanmukhan/Madhu Varanasi/Kala. Krishnankutty/ FACT Damu/Kalabharathi Unnikrishnan/Margi Ravindran 004 021 Thoranayuddham 16-10-06 2 Naripatta Narayanan Namputhiri/Kottarakkara Ganga/ Peesapally Rajeevan/Margi Harivalsan/Kala. Subramanyam/ Kalanilayam Nandakumar/Kala. Nandakumar/Kala. Sreekanth/ Kala. Venukuttan/Margi Baby 005 029 Keechakavadham (Whole story) 24/25-12-06 4 Kala. Krishnakumar/Margi. Vijayakumar/Sadanam Bhasi/ Kala. Kesavan Namputhiri/Kala. Shanmukhan/Kala. Prasanth/ Natyasala Suresh/Kottackal Ravikumar/Margi Suresh/Haripriya Namputhiri/Margi Murali/Kala. Krishnankutty/Kalanilayam Nanadakumar/Kalanilayam Rajeevan/Kala. Narayanan Varanasi/ Kalabharathi Unnikrishnan/Kala. Sreekanth/Margi Baby 006 030 Utharaswayamvaram 26/28/29-12-06 6 Kala. Balasubramanyam/Nelliyodu Vasudevan Namputhiri/ Inchakkat Ramachandran Pillai/Kottackal Chandrasekharan/ Kala. Anilkumar/Kala. Kalyanakrishnan/Kala. Vijayakumar/ Kala. Ratheesan/Kala. Mukundan/Attingal Peethambaran/Vishnu Nelliyodu/FACT -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology.