Mono Lake: Streams Taken and Given Back, but Still Waiting David B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Map of the Long Valley Caldera, Mono-Inyo Craters

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-1933 US. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF LONG VALLEY CALDERA, MONO-INYO CRATERS VOLCANIC CHAIN, AND VICINITY, EASTERN CALIFORNIA By Roy A. Bailey GEOLOGIC SETTING VOLCANISM Long Valley caldera and the Mono-Inyo Craters Long Valley caldera volcanic chain compose a late Tertiary to Quaternary Volcanism in the Long Valley area (Bailey and others, volcanic complex on the west edge of the Basin and 1976; Bailey, 1982b) began about 3.6 Ma with Range Province at the base of the Sierra Nevada frontal widespread eruption of trachybasaltic-trachyandesitic fault escarpment. The caldera, an east-west-elongate, lavas on a moderately well dissected upland surface oval depression 17 by 32 km, is located just northwest (Huber, 1981).Erosional remnants of these mafic lavas of the northern end of the Owens Valley rift and forms are scattered over a 4,000-km2 area extending from the a reentrant or offset in the Sierran escarpment, Adobe Hills (5-10 km notheast of the map area), commonly referred to as the "Mammoth embayment.'? around the periphery of Long Valley caldera, and The Mono-Inyo Craters volcanic chain forms a north- southwestward into the High Sierra. Although these trending zone of volcanic vents extending 45 km from lavas never formed a continuous cover over this region, the west moat of the caldera to Mono Lake. The their wide distribution suggests an extensive mantle prevolcanic basement in the area is mainly Mesozoic source for these initial mafic eruptions. Between 3.0 granitic rock of the Sierra Nevada batholith and and 2.5 Ma quartz-latite domes and flows erupted near Paleozoic metasedimentary and Mesozoic metavolcanic the north and northwest rims of the present caldera, at rocks of the Mount Morrisen, Gull Lake, and Ritter and near Bald Mountain and on San Joaquin Ridge Range roof pendants (map A). -

Ephydra Hians) Say at Mono Lake, California (USA) in Relation to Physical Habitat

Hydrobiologia 197: 193-205, 1990. F. A. Comln and T. G. Northcote (eds), Saline Lakes. 193 © 1990 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in Belgium. Distribution and abundance of the alkali fly (Ephydra hians) Say at Mono Lake, California (USA) in relation to physical habitat David B. Herbst Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory, University of California, Star Route 1, Box 198, Mammoth Lakes, CA 93546, USA Key words: Ephydra, life cycle, development, distribution, Mono Lake, substrate Abstract The distribution and abundance of larval, pupal, and adult stages of the alkali fly Ephydra hians Say were examined in relation to location, benthic substrate type, and shoreline features at Mono Lake. Generation time was calculated as a degree-day model for development time at different temperatures, and compared to the thermal environment of the lake at different depths. Larvae and pupae have a contagious distribution and occur in greatest abundance in benthic habitats containing tufa (a porous limestone deposit), and in least abundance on sand or sand/mud substrates. Numbers increase with increasing area of tufa present in a sample, but not on other rocky substrates (alluvial gravel/cobble or cemented sand). Standing stock densities are greatest at locations around the lake containing a mixture of tufa deposits, detrital mud sediments, and submerged vegetation. Shoreline adult abundance is also greatest in areas adjacent to tufa. The shore fly (ephydrid) community varies in composition among different shoreline habitats and shows a zonation with distance from shore. The duration of pupation (from pupa formation to adult eclosion) becomes shorter as temperature increases. The temperature dependence of pupa development time is not linear and results in prolonged time requirements to complete development at temperatures below 20 ° C. -

Yosemite, Lake Tahoe & the Eastern Sierra

Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe PCC EXTENSION YOSEMITE, LAKE TAHOE & THE EASTERN SIERRA FEATURING THE ALABAMA HILLS - MAMMOTH LAKES - MONO LAKE - TIOGA PASS - TUOLUMNE MEADOWS - YOSEMITE VALLEY AUGUST 8-12, 2021 ~ 5 DAY TOUR TOUR HIGHLIGHTS w Travel the length of geologic-rich Highway 395 in the shadow of the Sierra Nevada with sightseeing to include the Alabama Hills, the June Lake Loop, and the Museum of Lone Pine Film History w Visit the Mono Lake Visitors Center and Alabama Hills Mono Lake enjoy an included picnic and time to admire the tufa towers on the shores of Mono Lake w Stay two nights in South Lake Tahoe in an upscale, all- suites hotel within walking distance of the casino hotels, with sightseeing to include a driving tour around the north side of Lake Tahoe and a narrated lunch cruise on Lake Tahoe to the spectacular Emerald Bay w Travel over Tioga Pass and into Yosemite Yosemite Valley Tuolumne Meadows National Park with sightseeing to include Tuolumne Meadows, Tenaya Lake, Olmstead ITINERARY Point and sights in the Yosemite Valley including El Capitan, Half Dome and Embark on a unique adventure to discover the majesty of the Sierra Nevada. Born of fire and ice, the Yosemite Village granite peaks, valleys and lakes of the High Sierra have been sculpted by glaciers, wind and weather into some of nature’s most glorious works. From the eroded rocks of the Alabama Hills, to the glacier-formed w Enjoy an overnight stay at a Yosemite-area June Lake Loop, to the incredible beauty of Lake Tahoe and Yosemite National Park, this tour features lodge with a private balcony overlooking the Mother Nature at her best. -

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

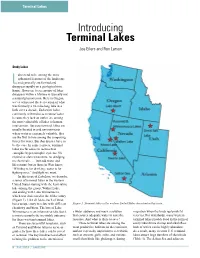

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Open-File/Color For

Questions about Lake Manly’s age, extent, and source Michael N. Machette, Ralph E. Klinger, and Jeffrey R. Knott ABSTRACT extent to form more than a shallow n this paper, we grapple with the timing of Lake Manly, an inconstant lake. A search for traces of any ancient lake that inundated Death Valley in the Pleistocene upper lines [shorelines] around the slopes Iepoch. The pluvial lake(s) of Death Valley are known col- leading into Death Valley has failed to lectively as Lake Manly (Hooke, 1999), just as the term Lake reveal evidence that any considerable lake Bonneville is used for the recurring deep-water Pleistocene lake has ever existed there.” (Gale, 1914, p. in northern Utah. As with other closed basins in the western 401, as cited in Hunt and Mabey, 1966, U.S., Death Valley may have been occupied by a shallow to p. A69.) deep lake during marine oxygen-isotope stages II (Tioga glacia- So, almost 20 years after Russell’s inference of tion), IV (Tenaya glaciation), and/or VI (Tahoe glaciation), as a lake in Death Valley, the pot was just start- well as other times earlier in the Quaternary. Geomorphic ing to simmer. C arguments and uranium-series disequilibrium dating of lacus- trine tufas suggest that most prominent high-level features of RECOGNITION AND NAMING OF Lake Manly, such as shorelines, strandlines, spits, bars, and tufa LAKE MANLY H deposits, are related to marine oxygen-isotope stage VI (OIS6, In 1924, Levi Noble—who would go on to 128-180 ka), whereas other geomorphic arguments and limited have a long and distinguished career in Death radiocarbon and luminescence age determinations suggest a Valley—discovered the first evidence for a younger lake phase (OIS 2 or 4). -

2021 Falling for the Migration

Falling for the Migration: Bridgeport, Crowley, Mono American Avocets in flight, photo by Bob Steele August 20–22, 2021 ● Dave Shuford $182 per person / $167 for Mono Lake Committee members enrollment limited to 10 participants Welcome to our field seminar on the fall migration of birds in the Bridgeport Valley and the adjacent Sierra, the Mono Basin, Crowley Lake, Long Valley, and the outskirts of Mammoth Lakes. Beginners as well as experts will enjoy this introduction to the area’s birdlife found in a wide variety of habitats, from the shimmering shores of Mono Lake to lofty Sierra peaks. We will identify about 100 species by plumage and calls, and probe the secrets of their natural history. This seminar will include informal discussions on migration strategies, behavior, and ecology that complement our field observations. This seminar will involve easy hiking at elevations ranging from 6,400 to 9,600 feet above sea level. We will hike 1–2 miles a day, mostly on level terrain. The first stop Friday morning is at Bridgeport Reservoir, a mecca for migrant and late‐breeding waterbirds. For those who prefer to meet the seminar at this location (arriving Friday morning from points north), please contact Nora Livingston at [email protected] or (760) 647‐6595 to obtain directions. Dave Shuford is an expert birder, avid naturalist and teacher, and a retired professional ornithologist. Dave’s bird research in the region includes a long‐term study on the ecology of Mono Lake’s California Gull colony, an atlas of breeding birds in the Glass Mountain area, and surveys of Snowy Plovers at Mono and Owens lakes. -

Chapter 3K. Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation Measures - Cultural Resources

Chapter 3K. Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation Measures - Cultural Resources This chapter addresses potential impacts of the alternatives on cultural resources in Mono Basin and Upper Owens River basin. Impacts are generally in the realm of potential disturbance to cultural resource sites from channel erosion, recreational activity, and restoration activities along the diverted streams and Owens River. Few effects would result from establishing higher or lower lake levels because no sites are expected to be present on the relicted lands. As described below, some diminishment in the use of the lake's food resources by Native Americans may have occurred during the diversion period, but choice of an alternative would little affect future resource utilization as long as resources of Native American importance are avoided during restoration activities. SOURCES OF INFORMATION Background Research A record search was conducted at the Eastern Information Center of the California Archaeological Inventory, University of California, Riverside, to determine the types and locations of known cultural resources within the areas of concern. Primary and secondary archeological, ethnographic, and historical sources were consulted for information pertaining to the areas of concern, including: # the National Register of Historic Places, # California Historical Landmarks, and # California Inventory of Historical Resources. Literature considered in this process is cited in the following discussions. Information on the Mono Lake Paiute is presented by Davis (1959, 1961, 1965, 1962, 1963, 1964), Curtis (1926), Kroeber (1925), and Merriam (1955, 1966:Part 1). Primary accounts of the Owens Valley Paiute are contained in Steward (1929, 1933, 1934, 1936, 1938a, 1938b). Additional information can be found in Davis (1961), Driver (1937), Kroeber (1925, 1939, 1959), and Merriam (1955). -

Biogeography and Physiological Adaptations of the Brine Fly Genus Ephydra (Diptera: Ephydridae) in Saline Waters of the Great Basin

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 59 Number 2 Article 3 4-30-1999 Biogeography and physiological adaptations of the brine fly genus Ephydra (Diptera: Ephydridae) in saline waters of the Great Basin David B. Herbst University of California, Mammoth Lakes and University of California, Santa Barbara Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Herbst, David B. (1999) "Biogeography and physiological adaptations of the brine fly genus Ephydra (Diptera: Ephydridae) in saline waters of the Great Basin," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 59 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol59/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 59(2), ©1999, pp. 127-135 BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYSIOLOGICAL ADAPTATIONS OF THE BRINE FLY GENUS EPHYDRA (DIPTERA: EPHYDRIDAE) IN SALINE WATERS OF THE GREAT BASIN David B. Herbst1 ABSTRACf.-Four species of the genus Ephydra are commonly found in saline waters within the hydrologic Great Basin: E. hians, E. gracilis, E. packardi, and E. auripes. Though none of these brine flies is endemic (distributions also occur outside the Great Basin), they all inhabit distinctive habitat types and form the characteristic benthic insect fauna ofinland saline-water habitats. The affinities ofeach species for different salinity levels and chemical compositions, and ephemeral to perennial habitats, appear to form the basis for biogeographic distribution patterns. -

Full Issue, Vol. 59 No. 2

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 59 Number 2 Article 16 4-30-1999 Full Issue, Vol. 59 No. 2 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation (1999) "Full Issue, Vol. 59 No. 2," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 59 : No. 2 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol59/iss2/16 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. T H E GREAT baslBASIBASIN naturalistNATURALI ST mot A VOLUME 59 NO 2 APRIL 1999 ML BEAN LIFE SCIENCE MUSEUM BRIGHAM YOUNG university GREAT BASIN naturalist httpwwwlibbyueduhttpwwwlibbyuedunmsamsnms FAX 8013783733801 378 3733 editor assistant editor richardwbaumannrighardRICHARD W BAUMANN NATHAN M SMITH 290 MLBM 190 MLBM PO box 20200 PO box 26879 brigham young university brigham young university provo UT 84602020084602 0200 provo UT 84602687984602 6879 8013785492801 378 5492 8013786688801 378 6688 emailE mail richarclbaumannbyuedurichardriehard baumannbyuedu emailE mail nathan smithbyuedu associate editors JAMES C CALLISON JR JERRY H SCRIVNER department of environmental technology department of biology utah valley state college ricks college orem UT 84058 redburgrexburgRexburg ID 83460110083460 1100 JEFFREY R JOHANSEN STANLEY D SMITH department of biology john carroll university -

Kutsavi, a Great Basin Indian Food

KUTSAVI, A GREAT BASIN INDIAN FOOD Robert F. Heizer When one becomes preoccupied with a topic or an area he ti apt to accumulate formidable piles of notee and references on cultural traits which are intriguing, but not highly significent. Often these accumu- lations evade utilization In the student's published works. The present note ts a by-product of a long and continuing interest in the archaeology and ethnology of the Great Basin, and because these data will probably never, to me have any particular significance, I offer them here in the hope that some other student may benefit from my literary gleanings. One of the most Interesting foods of tho Indians of the Intermon- tane-Platepu was kuteavi, the larva of a small fly (Ephydra hians Say) which was to be found from northern Neveda to Mono Lake on the eastern border of Celifornia. Native exploitation of this oconomic resource has been discusod by 0. Esslg (1) and J, Steward.(2) The present note will show the essential distribution of the use of Ephydra larvae ae. food. Among the earliest references to kutsavi collecttng at Mono Lake is that of Zenas Leonard in 1833. He BesY:k3) The water in ¾ihs lelke becomes stagnant and very disagreeable -- its surfece being covered with a green substence, similar to a. stagnant frog pond. In warm weether there is a. fly, about the size and similar to a grain of wheat, on this lake, in great num- bers. ... IWhen the wind rolls the waters onto the shore, these flies are left on the beech -- the female Indiens then carefully gether them into beekets made of willow .branches, and lay them exposed to the sun until they become perfectly dry, when theyg are laid away for winter provender.