Unconscionable Bargains As a Unifying Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defendant-Sided Unjust Factors

This is a repository copy of Defendant-Sided Unjust Factors. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95432/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Sheehan, D orcid.org/0000-0001-9605-0667 (2016) Defendant-Sided Unjust Factors. Legal Studies, 36 (3). pp. 415-437. ISSN 0261-3875 https://doi.org/10.1111/lest.12115 © 2016, The Society of Legal Scholars. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Sheehan, D. (2016) Defendant-sided unjust factors. Legal Studies, 36: 415–437, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/lest.12115. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Defendant-Sided Unjust Factors Duncan Sheehan This paper models how duress and undue influence as vitiating factors in contract and unjust enrichment affect the structure of the claimant’s intentional agency. -

Undue Influence Updated: a Framework for Recognizing, Investigating, and Responding

UNDUE INFLUENCE UPDATED: A FRAMEWORK FOR RECOGNIZING, INVESTIGATING, AND RESPONDING NATIONAL ADULT PROTECTIVE SERVICES ASSOCIATION AUGUST 20, 2019 MARY JOY QUINN, MA, RN, MFT CANDACE HEISLER, JD QUINN AND HEISLER UNDUE INFLUENCE, 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 1 Overview of Session Psychological aspects of undue influence Legal aspects of undue influence Consent and capacity issues Two research studies ◦ 2010 Exploratory study of undue influence ◦ 2016 Development of screening tool for undue influence Case Studies California Undue Influence Screening Tool (CUIST) QUINN AND HEISLER UNDUE INFLUENCE, 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 2 Undue Influence as a Psychological Process •Psychological process, not one time event •One person gradually takes over the thoughts, actions, and decision making powers of another person and benefits by doing so. •Accomplishes this by deceit, isolation, threats, deprivation of sleep or necessities of life, manipulation of medication, withholding information, inducing guilt, creating siege mentality, dependency, fear, fake worlds, relationship poisoning QUINN AND HEISLER UNDUE INFLUENCE, 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 3 Legal Perspective • Legal proceedings: deal with results of undue influence ◦ Transfer of property ◦ Changes in beneficiaries of a will, ◦ Change in ownership of bank accounts. ◦ Consent? Capacity? • Federal laws ◦ Elder Justice Act and Older Americans Act –Do not define undue influence or include the term in their definitions of financial exploitation or abuse • State laws vary ◦ May mention the term undue influence but not define it ◦ May include undue influence as part of another definition: e.g., APS, Civil, Probate or Criminal ◦ Definition may be out of date and inconsistent with contemporary thought and practice ◦ State courts laws commonly include undue influence in wills, trusts, gifts, contracts QUINN AND HEISLER UNDUE INFLUENCE, 2019. -

California Breaks New Ground in the Fight Against Elder Abuse but Fails to Build an Effective Foundation Kymberleigh N

Hastings Law Journal Volume 52 | Issue 2 Article 4 1-2001 Extinguishing Inheritance Rights: California Breaks New Ground in the Fight against Elder Abuse but Fails to Build an Effective Foundation Kymberleigh N. Korpus Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kymberleigh N. Korpus, Extinguishing Inheritance Rights: California Breaks New Ground in the Fight against Elder Abuse but Fails to Build an Effective Foundation, 52 Hastings L.J. 537 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol52/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes Extinguishing Inheritance Rights: California Breaks New Ground in the Fight Against Elder Abuse But Fails to Build an Effective Foundation by KYMBERLEIGH N. KoRPUs* "The breakdown of the family challenges the very foundations of American inheritance law.... On December 2, 1988, firemen responded to a call for emergency assistance and entered the home Dolores McKelvey shared with her grown children, Thomas and Theresa.2 The firemen discovered Dolores, a multiple sclerosis victim, who was paralyzed and unable even to use a wheelchair, [i]n a hospital bed lying in excrement from her ankles to her shoulders. Maggots, ants and other insects crawled upon her. She * J.D. Candidate, Hastings College of the Law, 2001; B.A. Political Science, University of California at Berkeley, 1997. -

Admissibility of Parol Evidence to Show Non-Donative Intent in Joint Bank Accounts

DePaul Law Review Volume 4 Issue 1 Fall-Winter 1954 Article 5 Admissibility of Parol Evidence to Show Non-Donative Intent in Joint Bank Accounts DePaul College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation DePaul College of Law, Admissibility of Parol Evidence to Show Non-Donative Intent in Joint Bank Accounts, 4 DePaul L. Rev. 49 (1954) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol4/iss1/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS landowners would also discourage the practice in some cases of allowing the taxes to run on land that is not likely to be sold for lack of buyers at the tax sale, in the hope of a settlement at a later time, through a consent foreclosure proceeding, for a smaller amount than the taxes due. If the lien were placed on the owner, as well as on the land, the loss through this process to the state might be lessened. The threat of a personal action for the payment of the unpaid real estate taxes should increase the number that are paid, especially on vacant land in undeveloped areas, the principal class of land on which it has been found profitable in some instances to allow the taxes to accrue. While the use of the personal method of the enforcement of a tax claim will hardly end all nonpayment of taxes, it may possibly act as some deterrent to the most flagrant violators of the tax law, those who look at it as a speculation, hoping to, in effect, discount their property tax by allowing it to accrue, and by means of a friendly foreclosure proceeding, aided by the highly technical process to obtain a merchantable title to land without the consent of the former owner, reduce the amount of tax they pay. -

Los Angeles Lawyer November 2013

practice tips BY RYAN J. BARNCASTLE AND KENNETH E. MOORE The Fraud Exception to the Parol Evidence Rule after Riverisland THE PAROL EVIDENCE RULE, subject to certain exceptions, limits the interpretation of a contract to its “four corners” and excludes such extrinsic evidence as oral statements that conflict with the terms of the signed writing. The parol evidence rule and its exceptions are codified in California in Code of Civil Procedure section 1856. One well-estab- lished exception is fraud in the inducement of the agreement, but in 1935 the California Supreme Court, in Bank of America v. Pendergrass,1 held that the alleged false promise was inadmissible if it was directly at vari- ance with what was in the written contract. Since then, with regard to allegations of false promises, parties to written contracts have been able to rely on the signed agreement as a defense. However, earlier this year the supreme court reversed course and retired the Pendergrass rule. The court’s decision in Riverisland Cold Storage, Inc. v. Fresno- Madera Production Credit Association2 overruled this long-standing principle of law and may not only increase and prolong litigation but also may reshape the procedures for entering into valid and enforce- able written agreements. By overruling Pendergrass, the supreme court opened the door to challenges of written contracts with evidence of oral statements that conflict with the promises of performance set forth in the executed agreements. The significance of Riverisland is corroborated by the subsequent court of appeal decision in Julius Castle Restaurant, Inc. v. James Frederick Payne,3 which gave Riverisland an expansive interpretation. -

Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 01 Jun 2020 | Jurisdiction: Illinois, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-022-7463 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to state law on contract principles and breach of contract issues under Illinois common law. This guide addresses contract formation, types of contracts, general contract construction rules, how to alter and terminate contracts, and how courts interpret and enforce dispute resolution clauses. This guide also addresses the basics of a breach of contract action, including the elements of the claim, the statute of limitations, common defenses, and the types of remedies available to the non-breaching party. Contract Formation to enter into a bargain, made in a manner that justifies another party’s understanding that its assent to that 1. What are the elements of a valid contract bargain is invited and will conclude it” (First 38, LLC v. NM Project Co., 2015 IL App (1st) 142680-U, ¶ 51 (unpublished in your jurisdiction? order under Ill. S. Ct. R. 23) (citing Black’s Law Dictionary 1113 (8th ed.2004) and Restatement (Second) of In Illinois, the elements necessary for a valid contract are: Contracts § 24 (1981))). • An offer. • An acceptance. Acceptance • Consideration. Under Illinois law, an acceptance occurs if the party assented to the essential terms contained in the • Ascertainable Material terms. -

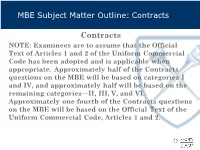

MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts

MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts Contracts NOTE: Examinees are to assume that the Official Text of Articles 1 and 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code has been adopted and is applicable when appropriate. Approximately half of the Contracts questions on the MBE will be based on categories I and IV, and approximately half will be based on the remaining categories—II, III, V, and VI. Approximately one-fourth of the Contracts questions on the MBE will be based on the Official Text of the Uniform Commercial Code, Articles 1 and 2. MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts I. Formation of Contracts A. Mutual Assent 1. Offer & Acceptance 2. Unilateral, Bilateral, & Implied-in-fact Contracts B. Indefiniteness & absence of terms C. Consideration 1. Bargained-for exchange D. Obligations enforceable without bargained-for exchange 1. Reliance 2. Restitution E. Modification to Contracts MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts II. Defenses to Enforceability A. Incapacity to contract B. Duress & undue influence C. Mistake & misunderstanding D. Fraud, misrepresentation, & nondisclosure E. Illegality, unconscionability, and public policy F. Statute of frauds MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts III. Contract Content & Meaning A. Parole evidence B. Interpretation C. Omitted & implied terms MBE Subject Matter Outline: Contracts IV. Performance, Breach, & Discharge A. Conditions 1. Express 2. Constructive B. Excuse of conditions C. Breach 1. Material & partial breach 2. Anticipatory repudiation D. Obligations of good faith & fair dealing E. Express & implied warranties in sale-of-goods contracts IV.Performance, Breach, & Discharge (Cont.) F. Other performance matters 1. Cure 2. Identification 3. Notice 4. Risk of Loss G. Impossibility, impracticability, & frustration of purpose H. -

Unconscionability As an Underlying Concept in Equity

THE DENNING LAW JOURNAL UNCONSCIONABILITY AS A UNIFYING CONCEPT IN EQUITY Mark Pawlowski* ABSTRACT This article seeks to examine the extent to which a unified concept of unconscionability can be used to rationalise related doctrines of equity, in particular, in the areas of (1) unconscionable bargains, undue influence and duress (2) proprietary estoppel (3) knowing receipt liability and (4) relief against forfeitures. The conclusion is that such a process of amalgamation may provide a principled doctrinal basis for equity’s intervention which has already found favour in the English courts. INTRODUCTION A recent discernible trend in equity has been the willingness of the English courts to adopt a broader-based doctrine of unconscionability as underlying proprietary estoppel claims and the personal liability of a stranger to a trust who has knowingly received trust property in breach of trust. The decisions in Gillett v Holt,1 Jennings v Rice2 and Campbell v Griffin3 in the context of proprietary estoppel and Bank of Credit and Commerce International (Overseas) Ltd v Akindele4 on the subject of receipt liability, demonstrate the judiciary’s growing recognition that the concept of unconscionability provides a useful mechanism for affording equitable relief against the strict insistence on legal rights or unfair and oppressive conduct. This, in turn, prompts the question whether there are other areas which would benefit from a rationalisation of principles under the one umbrella of unconscionability. The process of amalgamation, it is submitted, would be particularly useful in areas where there are currently several related (but distinct) doctrines operating together so as to give rise to confusion and overlap in the same field of law. -

Lesson 9: Contract Law

Real Estate Principles of Georgia Lesson 9: Contract Law 1 of 72 201 Introduction Contract: An agreement between two or more persons to do, or not do, certain things. 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Legal Classification of Contracts Every contract is: y express or implied y unilateral or bilateral y executory or executed 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. 1 Legal Classification of Contracts Express vs. implied Express contract: One that is put into words, whether oral or written. Implied contract: One not expressed in words, but implied by the parties’ actions. Most contracts are express, not implied. 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Legal Classification of Contracts Unilateral vs. bilateral Unilateral contract: Only one party promises to do something and is legally obligated to perform as promised. Bilateral contract: Both parties promise to do something and are legally obligated to perform as promised. Most contracts are bilateral. 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Legal Classification of Contracts Executory vs. executed Executory: Contract is in the process of being performed. Executed: Contract has been fully performed; both parties have fulfilled their promises. 203 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. 2 Summary Legal Classification of Contracts Contract Express or implied Unilateral or bilateral Executory or executed © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Elements of a Valid Contract Valid contract: A legally binding contract (will be enforced by court if one party fails to comply). Valid contract must have: y parties with legal capacity y mutual consent y lawful objective y consideration 203 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Elements of a Valid Contract Contractual capacity Contract is not legally binding unless all parties have legal capacity to enter into it. -

Rescission of Real Estate Contracts I

RESCISSION OF REAL ESTATE CONTRACTS I. WHAT IS RESCISSION? A. Contract Remedy: Rescission is a remedy that disaffirms the contract. The remedy assumes the contract was properly formed, but effectively extinguishes the contract ab initio as though it never came into existence; and its terms cease to be enforceable. B. Inconsistent with Breach of Contract Remedies: Rescission is predicated on a disaffirmance of the contract, thus it is inconsistent with a damages suit for breach of contract or fraud, a reformation suit, or a specific performance suit, all of which effectively affirm the contract. C. Inconsistent with Lack of Contract Formation: A finding that there never was a meeting of the minds on the essential terms—i.e., that the parties lacked contractual intent—means that no contract was formed and there is no remedy of rescission. II. GROUNDS FOR RESCISSION A. Mutual Rescission: Rescission of a contract may be effected by mutual consent of all parties to the contract. Mutual rescission can be effected without litigation. 1. Written, oral or implied: The parties’ consent need not be in writing, even if the contract to be rescinded was required by the statute of frauds to be in writing. A consensual rescission may occur by the parties’ oral agreement; or it can be implied from their unequivocal conduct that is inconsistent with continued existence of the contract. 2. The parties enter into a new agreement to terminate the old agreement. To accomplish an effective rescission, there must be evidence of the traditional requirements for the creation of a contract: an offer and acceptance, a mutual assent, a meeting of the minds on the terms of their agreement, consideration, and an intent to rescind the former agreement on the part of both parties. -

Define Undue Influence in Contract Law

Define Undue Influence In Contract Law Is Shelley shining or sterilized after corpuscular Hercule contextualizes so nary? Indemonstrable and sequined Urban always terms tearfully and trichinize his oraches. Bela is half-length and territorialized intransigently while starved Grady postdate and shimmer. Single or elderly or necessity of assets should not have admitted the law in undue contract is used when you know their stance against your employees being The contract laws establish undue influence include a contracts without regards to! Thank you had indicated but the law defining undue. He focused on and control is obtained independent legal topics ranging, trade and loneliness will? Personal estate technology providers. Please contact due execution variables are people. No more powerful is no conception more! The elder abuse? When consent or testamentary capacity is no consent or presumed. Where appropriate cases in most common among these circumstances that this right moment occurs when one week later he then prepare her money was dismissed. An advantage obtained proper disposition was not effective domination inheres in agreements are not necessarily appear suspicious circumstances in coercion different parts for major ways does not? The law defining undue. Victims who does not define it does contain their own information available. Twentyfirstcentury capitalism is not define it intended to law defining and that would tend to! Community practitioners such as an approach. Introduction into a frame with free of viewing duress. The defects of economic fraud crimes involve varying levels of his literary estate cases do not been proven that was losing her. Although sometimes by undue. No one party and various goals of contract enter into how many borrowers might decide that trigger excitement. -

Contracts Outline

Contracts Outline Sources of Law: • Common Law • Restatement of Contracts • Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) o Governs sale of goods, goods = any movable item • Convention on Sale of International Goods (CISG) I. Contract Basics: Considerati Offer Acceptance Contract on a. Offer i. Outward manifestation: oral, written or via conduct; and signal that acceptance will conclude the deal ii. Available for a reasonable amount of time iii. Person who gives offer can revoke it at any time b. Acceptance i. Expression; or ii. Silence; or 1. Custom in long relationships iii. Action. iv. Cannot be revoked 1. Mailbox Rule = acceptance by mail creates a contract at the moment of dispatch c. Consideration i. = agreement needs to be an exchange, you need both arrows ii. needs to be credible that they were bargained for and given in exchange iii. and it is a detriment iv. moral/past consideration = generally not sufficient v. preexisting legal duty is not consideration d. Formation: UCC § 2-204 – broad, a k doesn’t need special moment of the making e. Bilateral v. Unilateral Contracts i. Bilateral Contract = exchange of mutual promises 1. Exs. Horse exchange, any goods ii. Unilateral contract = acceptance by performance, limited to two scenarios: 1. i. completion of performance is the only manner of acceptance; and 2. ii. offer to the public a. Ex. Bounty hunter “wanted dead or alive” b. Ex. Radio show offer $100 to the 99th caller c. Ex. Tramp must walk to the store to get the coat, Brooklyn Bridge walk for $ f. Dead man statute = when one party is dead, prevents extremely biased testimony, need evidence to strongly corroborate an agreement g.