A Socio-Historical Profile of the Nomads in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muzaffargarh

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - Muzaffargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhattiwala Kherawala !Molewala Siwagwala ! Mari PuadhiMari Poadhi LelahLeiah ! ! Chanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ladhranwala Kherawala! ! ! ! Lerah Tindawala Ahmad Chirawala Bhukwala Jhang Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala ! Pehar MorjhangiMarjhangi Anwarwal!a Khairewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wali Dadwala MuhammadwalaJindawala Faqirewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MalkaniRetra !Shah Alamwala ! Bhindwalwala ! ! ! ! ! Patti Khar ! ! ! Dargaiwala Shah Alamwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sultanwala ! ! Zubairwa(24e6)la Vasawa Khiarewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Jhok Bodo Mochiwala PakkaMochiwala KumharKumbar ! ! ! ! ! ! Qaziwala ! Haji MuhammadKhanwala Basti Dagi ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala Vasawa ! ! ! Mirani ! ! Munnawala! ! ! Mughlanwala ! Le! gend ! Sohnawala ! ! ! ! ! Pir Shahwala! ! ! Langanwala ! ! ! ! Chaubara ! Rajawala B!asti Saqi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BuranawalaBuranawala !Gullanwala ! ! ! ! ! Jahaniawala ! ! ! ! ! Pathanwala Rajawala Maqaliwala Sanpalwala Massu Khanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhandniwal!a Josawala ! ! Basti NasirBabhan Jaman Shah !Tarkhanwala ! !Mohanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basti Naseer Tarkhanwala Mohanawala !Citiy / Town ! Sohbawala ! Basti Bhedanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohaganwala Bhurliwala ! ! ! ! Thattha BulaniBolani Ladhana Kunnal Thal Pharlawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ganjiwala Pinglarwala Sanpal Siddiq Bajwa ! ! ! ! ! Anhiwala Balochanwala ! Pahrewali ! ! Ahmadwala ! ! ! -

Final Merit List of Candidates Applied for Admission in Bs Medical Laboratory

BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION - 2020-2021 FINAL MERIT LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR ADMISSION IN BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION 2020-2021 LIAQUAT UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, JAMSHORO DISTRICT - BADIN (BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) - 01 - SEAT - MERIT) Test Test Int. Total Merit Inter A / Level Test Form No. Name of Candidates Fathers Name Surname Gender DOB District Seat Marks 50% score Positon Obt 50% Year Inter% Grade No. Marks 1 4841 Habesh Kumar Veero Mal Khattri Male 1/11/2001 BADIN 2019 905 82.273 A1 719 82 41 41.136 82.136 District: BADIN - WAITING Menghwar 1496 Akash Kumar Mansingh Male 10/16/2001 BADIN 2020 913 83 A1 167 78 39 41.5 80.5 2 Bhatti 3 1215 Janvi Papoo Kumar Lohana Female 2/11/2002 BADIN 2020 863 78.455 A 894 82 41 39.227 80.227 4 3344 Bushra Muhammad Ayoub Kamboh Female 9/30/2000 BADIN 2019 835 75.909 A 490 82 41 37.955 78.955 5 1161 Chanderkant Papoo Kumar Lohana Male 3/8/2003 BADIN 2020 889 80.818 A1 503 76 38 40.409 78.409 6 3479 Bushra Amjad Amjad Ali Jat Female 4/20/2001 BADIN 2019 848 77.091 A 494 73 36.5 38.545 75.045 7 4306 Noor Ahmed Ghulam Muhammad Notkani Male 10/12/2001 BADIN 2020 874 79.455 A 1575 70 35 39.727 74.727 Muhammad Talha 2779 Hasan Nasir Rajput Male 7/21/2001 BADIN 2020 927 84.273 A1 1378 65 32.5 42.136 74.636 8 Nasir 9 3249 Vandna Dev Anand Lohana Female 3/21/2002 BADIN 2020 924 84 A1 2294 65 32.5 42 74.5 10 2231 Sanjai Eshwar Kumar Luhano Male 8/17/2000 BADIN 2020 864 78.546 A 1939 70 35 39.273 74.273 RANA RAJINDAR 3771 RANA AMAR -

Public Sector Development Programme 2019-20 (Original)

GOVERNMENT OF BALOCHISTAN PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT PUBLIC SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2019-20 (ORIGINAL) Table of Contents S.No. Sector Page No. 1. Agriculture……………………………………………………………………… 2 2. Livestock………………………………………………………………………… 8 3. Forestry………………………………………………………………………….. 11 4. Fisheries…………………………………………………………………………. 13 5. Food……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 6. Population welfare………………………………………………………….. 16 7. Industries………………………………………………………………………... 18 8. Minerals………………………………………………………………………….. 21 9. Manpower………………………………………………………………………. 23 10. Sports……………………………………………………………………………… 25 11. Culture……………………………………………………………………………. 30 12. Tourism…………………………………………………………………………... 33 13. PP&H………………………………………………………………………………. 36 14. Communication………………………………………………………………. 46 15. Water……………………………………………………………………………… 86 16. Information Technology…………………………………………………... 105 17. Education. ………………………………………………………………………. 107 18. Health……………………………………………………………………………... 133 19. Public Health Engineering……………………………………………….. 144 20. Social Welfare…………………………………………………………………. 183 21. Environment…………………………………………………………………… 188 22. Local Government ………………………………………………………….. 189 23. Women Development……………………………………………………… 198 24. Urban Planning and Development……………………………………. 200 25. Power…………………………………………………………………………….. 206 26. Other Schemes………………………………………………………………… 212 27. List of Schemes to be reassessed for Socio-Economic Viability 2-32 PREFACE Agro-pastoral economy of Balochistan, periodically affected by spells of droughts, has shrunk livelihood opportunities. -

Malir-Karachi

Malir-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180381 GBLSS - HUSSAIN BLAOUCH Middle Boys 14,324 2,865 8,594 5,729 2,865 11,459 45,836 11,459 57,295 2 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180436 GBELS - HAJI IBRAHIM BALOUCH Elementary Mixed 24,559 4,912 19,647 4,912 4,912 19,647 78,588 19,647 98,236 3 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180426 GBELS - HASHIM KHASKHELI Elementary Boys 42,250 8,450 33,800 8,450 8,450 33,800 135,202 33,800 169,002 4 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180434 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 OLD Elementary Mixed 35,865 7,173 28,692 7,173 7,173 28,692 114,769 28,692 143,461 5 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180435 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 NEW Elementary Mixed 24,882 4,976 19,906 4,976 4,976 19,906 79,622 19,906 99,528 6 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180073 GBELS - AL-HAJ DUR MUHAMMAD BALOCH Elementary Boys 36,374 7,275 21,824 14,550 7,275 29,099 116,397 29,099 145,496 7 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180428 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.1 Elementary Mixed 33,116 6,623 26,493 6,623 6,623 26,493 105,971 26,493 132,464 8 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 3-Gujhro 408180441 GBELS - SIRAHMED VILLAGE Elementary Mixed 38,725 7,745 30,980 7,745 7,745 30,980 123,919 -

Oscillating in a Chasm 2 | P a G E

SPEARHEAD RESEARCH 1 | P a g e SPECIAL REPORT October 2012 Balochistan: Oscillating in a Chasm 2 | P a g e Balochistan: Oscillating in a Chasm By Zoon Ahmed Khan http://spearheadresearch.org Email: [email protected] Tel: +92 42 3662 2335 +92 42 3662 2336 Fax: +92 42 3662 2337 Office 17, 2nd Floor, Parklane Towers, 172 Tufail Road, Cantonment Lahore - Pakistan 3 | P a g e Abstract “Rule the Punjabis, intimidate the Sindhis, buy the Pashtun and honour the Baloch” For the colonial master a delicate balance between resource exploitation and smooth governance was the fundamental motive. Must we assume that this mindset has seeped into the governmentality of Islamabad? And if it has worked: are these provinces in some way reflective of stereotypes strong enough to be regarded as separate nations? These stereotypes are reflective of the structural relationships in these societies and have been discovered, analyzed and, at times, exploited. In the Baloch case the exploitation seems to have become more apparent because this province has been left in the waiting room of history through the prisms of social, political and economic evolution. Balochistan’s turmoil is a product of factors that this report will address. Looking into the current snapshot, and stakeholders today, the report will explain present in the context of a past that media, political parties and other stakeholders are neglecting. 4 | P a g e 5 | P a g e Contents Introduction: ............................................................................................................................ -

“TELLING the STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: a Regional Perspective (2011-2016)

“TELLING THE STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective (2011-2016) Emma Hooper (ed.) This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. © 2016 CIDOB This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. CIDOB edicions Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona Tel.: 933 026 495 www.cidob.org [email protected] D.L.: B 17561 - 2016 Barcelona, September 2016 CONTENTS CONTRIBUTOR BIOGRAPHIES 5 FOREWORD 11 Tine Mørch Smith INTRODUCTION 13 Emma Hooper CHAPTER ONE: MAPPING THE SOURCES OF TENSION WITH REGIONAL DIMENSIONS 17 Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective .......... 19 Zahid Hussain Mapping the Sources of Tension and the Interests of Regional Powers in Afghanistan and Pakistan ............................................................................................. 35 Emma Hooper & Juan Garrigues CHAPTER TWO: KEY PHENOMENA: THE TALIBAN, REFUGEES , & THE BRAIN DRAIN, GOVERNANCE 57 THE TALIBAN Preamble: Third Party Roles and Insurgencies in South Asia ............................... 61 Moeed Yusuf The Pakistan Taliban Movement: An Appraisal ......................................................... 65 Michael Semple The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan ....................................................................... -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

Reimagine a F G H a N I S T a N

REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N A N I N I T I A T I V E B Y R A I S I N A H O U S E REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N INTRODUCTION . Afghanistan equals Culture, heritage, music, poet, spirituality, food & so much more. The country had witnessed continuous violence for more than 4 ................................................... decades & this has in turn overshadowed the rich cultural heritage possessed by the country, which has evolved through mellinnias of Cultural interaction & evolution. Reimagine Afghanistan as a digital magazine is an attempt by Raisina House to explore & portray that hidden side of Afghanistan, one that is almost always overlooked by the mainstream media, the side that is Humane. Afghanistan is rich in Cultural Heritage that has seen mellinnias of construction & destruction but has managed to evolve to the better through the ages. Issued as part of our vision project "Rejuvenate Afghanistan", the magazine is an attempt to change the existing perception of Afghanistan as a Country & a society bringing forward that there is more to the Country than meets the eye. So do join us in this journey to explore the People, lifestyle, Art, Food, Music of this Adventure called Afghanistan. C O N T E N T S P A G E 1 AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY PROFILE P A G E 2 - 4 PEOPLE ETHNICITY & LANGUAGE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 5 - 7 ART OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 8 ARTISTS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 9 WOOD CARVING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 0 GLASS BLOWING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 1 CARPETS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 2 CERAMIC WARE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 3 - 1 4 FAMOUS RECIPES OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 5 AFGHANI POETRY P A G E 1 6 ARCHITECTURE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 7 REIMAGINING AFGHANISTAN THROUGH CINEMA P A G E 1 8 AFGHANI MOVIE RECOMMENDATION A B O U T A F G H A N I S T A N Afghanistan Country Profile: The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is a landlocked country situated between the crossroads of Western, Central, and Southern Asia and is at the heart of the continent. -

Motion Anwar Lal Dean, Bahramand Khan Tangi

SENATE SECRETARIAT ORDERS OF THE DAY for the meeting of the Senate to be held at 02:00 p.m. on Thursday, the 1'r August, 20 19. 1, Recitation from the Holy Quran. MOTION 2, SENATORS RAJA MUHAMMAD ZAFAR-UL-HAQ, LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION, ATTA UR REHMAN, MOLVI FAIZ MUHAMMAD, ABIDA MUHAMMAD AZEEM, AGHA SHAHZAIB DURRANI, RANA MAHMOOD UL HASSAN, PERVAIZ RASHEED, MUSADIK MASOOD MALIIC SITARA AYAZ, MUHAMMAD JAVED ABBASI, MUHAMMAD USMAN KHAN KAKAR, MIR KABEER AHMED MUHAMMAD SHAHI, MOLANA ABDUL GHAFOOR HAIDERI, MUHAMMAD TAHIR BIZINJO, MUSHAHID ULLAH KHAN, SALEEM ZIA, MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI KHAN JUNEJO, GHOUS MUHAMMAD KHAN NIAZI, RANA MAQBOOL AHMAD, DR. ASIF KIRMANI, DR. ASAD ASHRAF, SARDAR MUHAMMAD SHAFIQ TAREEN, SHERRY REHMAN, MIAN RAZA RABBANI, FAROOQ HAMID NAEK, ABDUL REHMAN MALIK DR. SIKANDAR MANDHRO, ISLAMUDDIN SHAIKH, RUBINA KHALID, GIANCHAND, KHANZADA KHAN, SASSUI PALIJO, MOULA BUX CHANDIO, MUSTAFA NAWAZ KHOKHA& SYED MUHAMMAD ALI SHAH ]AMOT, IMAMUDDIN SHOUQEEN, ENGR. RUKHSANA ZUBERI, QURATULAIN MARRI, KESHOO BAI, ANWAR LAL DEAN, BAHRAMAND KHAN TANGI AND MIR MUHAMMAD YOUSAF BADINI, tO MOVC,- "That leave be granted to move a resolution for the removal of Senator Muhammad Sadiq Sanjrani from the office of the Chairman, Senate of Pakistan." 2 RESOLUTION 3. SENATORS RAJA MUHAMMAD ZAFAR-UL-HAQ, LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION, ATTA UR REHMAN, MOLVI FAIZ MUHAMMAD, ABIDA MUHAMMAD AZEEMI AGHA SHAHZAIB DURRANI' RANA MAHMOOD UL HASSAN, PERVAIZ RASHEED, MUSADIK MASOOD MALIK, SITARA AYAZ, MUHAMMAD JAVED ABBASI, MUHAMMAD USMAN KHAN KAKAR, MIR KABEER AHMED MUHAMMAD SHAHI, MOLANA ABDUL GHAFOOR HAIDERT, MUHAMMAD TAHIR BIZINJO, MUSHAHID ULLAH KHAN, SALEEM ZI^^ MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI KHAN JUNEJO, GHOUS MUHAMMAD KHAN NIAZI, RIANA MAQBOOL AHMAD, DR. -

UNIVERSITA CA'foscari VENEZIA CHAUKHANDI TOMBS a Peculiar

UNIVERSITA CA’FOSCARI VENEZIA Dottorato di Ricerca in Lingue Culture e Societa` indirizzo Studi Orientali, XXII ciclo (A.A. 2006/2007 – A. A. 2009/2010) CHAUKHANDI TOMBS A Peculiar Funerary Memorial Architecture in Sindh and Baluchistan (Pakistan) TESI DI DOTTORATO DI ABDUL JABBAR KHAN numero di matricola 955338 Coordinatore del Dottorato Tutore del Dottorando Ch.mo Prof. Rosella Mamoli Zorzi Ch.mo Prof. Gian Giuseppe Filippi i Chaukhandi Tombs at Karachi National highway (Seventeenth Century). ii AKNOWLEDEGEMENTS During my research many individuals helped me. First of all I would like to offer my gratitude to my academic supervisor Professor Gian Giuseppe Filippi, Professor Ordinario at Department of Eurasian Studies, Universita` Ca`Foscari Venezia, for this Study. I have profited greatly from his constructive guidance, advice, enormous support and encouragements to complete this dissertation. I also would like to thank and offer my gratitude to Mr. Shaikh Khurshid Hasan, former Director General of Archaeology - Government of Pakistan for his valuable suggestions, providing me his original photographs of Chuakhandi tombs and above all his availability despite of his health issues during my visits to Pakistan. I am also grateful to Prof. Ansar Zahid Khan, editor Journal of Pakistan Historical Society and Dr. Muhammad Reza Kazmi , editorial consultant at OUP Karachi for sharing their expertise with me and giving valuable suggestions during this study. The writing of this dissertation would not be possible without the assistance and courage I have received from my family and friends, but above all, prayers of my mother and the loving memory of my father Late Abdul Aziz Khan who always has been a source of inspiration for me, the patience and cooperation from my wife and the beautiful smile of my two year old daughter which has given me a lot courage. -

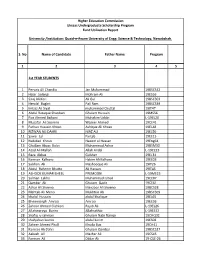

S. No Name of Candidate Father Name Program 1 2 3 4 5 1St YEAR STUDENTS 1 Pervaiz Ali Chandio Jan Muhammad 19BSCS42 2 Halar

Higher Education Commission Ehsaas Undergraduate Scholarship Program Fund Utilization Report University /Institution: Quaid-e-Awam University of Engg: Science & Technology, Nawabshah. S. No Name of Candidate Father Name Program 1 2 3 4 5 1st YEAR STUDENTS 1 Pervaiz Ali Chandio Jan Muhammad 19BSCS42 2 Halar Solangi Mohram Ali 19ES16 3 Siraj Ali Kori Ali Gul 19BSCS03 4 Heralal Baghri Pali Ram 19BSCS39 5 Imtiaz Ali Siyal muhammad Chuttal 19IT47 6 Abdul Razaque Shanbani Ghulam Hussain 19MS56 7 Fiaz Ahmed Bajkani Muhakim Uddin L-19EL20 8 Muzafar Ali Soomro Wazeer Ahmed 19CE41 9 Farhan Hussain Khoso Ashique Ali Khoso 19EL48 10 RIZWAN ALI DAHRI NIAZ ALI 19EL50 11 Sawai Lal Partab 19EE15 12 Nabidad Khoso Naeem ul Hassan 19Eng64 13 Ghullam Abass Kaloi Muhammad Achar 19BSM30 14 Azad Ali Mallah Allah Andal L-19CE23 15 Raza Abbas Gulsher 19EL34 16 Kamran Kalhoro Hakim Ali Kalhoro 19EE03 17 Subhan Ali Mashooque Ali 19IT26 18 Abdul Raheem Bhutto Ali Hassan 19IT45 19 ASHOOK KUMAR BHEEL PREMOON L-19ME23 20 Salman Lakho Muhammad Ismail 19CE07 21 Qambar Ali Ghulam Qadir 19CE61 22 Azhar Ali Sheeno Manzoor Ali Sheeno 19BCS28 23 Mehtab Ali Meno Mukhtiar Ali 19BSCS09 24 khalid Hussain abdul khalique 19EL65 25 Bheemsingh Amroo Amroo 19EE36 26 Zahoor Ahmed Gishkori Rajab Ali L-19EL26 27 Allahwarayo Buriro Allahrakhio L-19ES32 28 Shafiq u rahman Ghulam Nabi Narejo 19CHQ32 29 shahjahan keerio abdul karim 19ES02 30 Zaheer Ahmed Phull Khuda Bux 19CH41 31 Kamran Ali Dahri Ghulam Qambar 19BSCS27 32 Aakash Ali Mazhar Ali 19CS45 33 Farman Ali Dildar Ali 19-CSE-26 34 -

Chronologica Dictionary of Sind Chronologial Dictionary of Sind

CHRONOLOGICA DICTIONARY OF SIND CHRONOLOGIAL DICTIONARY OF SIND (From Geological Times to 1539 A.D.) By M. H. Panhwar Institute of Sindhology University of Sind, Jamshoro Sind-Pakistan All rights reserved. Copyright (c) M. H. Panhwar 1983. Institute of Sindhology Publication No. 99 > First printed — 1983 No. of Copies 2000 40 0-0 Price ^Pt&AW&Q Published By Institute of Sindhlogy, University of Sind Jamshoro, in collabortion with Academy of letters Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Education Islamabad. Printed at Educational Press Dr. Ziauddin Ahmad Road, Karachi. • PUBLISHER'S NOTE Institute of Sindhology is engaged in publishing informative material on - Sind under its scheme of "Documentation, Information and Source material on Sind". The present work is part of this scheme, and is being presented for benefit of all those interested in Sindhological Studies. The Institute has already pulished the following informative material on Sind, which has received due recognition in literary circles. 1. Catalogue of religious literature. 2. Catalogue of Sindhi Magazines and Journals. 3. Directory of Sindhi writers 1943-1973. 4. Source material on Sind. 5. Linguist geography of Sind. 6. Historical geography of Sind. The "Chronological Dictionary of Sind" containing 531 pages, 46 maps 14 charts and 130 figures is one of such publications. The text is arranged year by year, giving incidents, sources and analytical discussions. An elaborate bibliography and index: increases the usefulness of the book. The maps and photographs give pictographic history of Sind and have their own place. Sindhology has also published a number of articles of Mr. M.H. Panhwar, referred in the introduction in the journal Sindhology, to make available to the reader all new information collected, while the book was in press.