Katanga Calling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FROM COERCION to COMPENSATION INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSES to LABOUR SCARCITY in the CENTRAL AFRICAN COPPERBELT African Economic

FROM COERCION TO COMPENSATION INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSES TO LABOUR SCARCITY IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN COPPERBELT African economic history working paper series No. 24/2016 Dacil Juif, Wageningen University [email protected] Ewout Frankema, Wageniningen University [email protected] 1 ISBN 978-91-981477-9-7 AEHN working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. The papers have not been peer reviewed, but published at the discretion of the AEHN committee. The African Economic History Network is funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Sweden 2 From Coercion to Compensation Institutional responses to labour scarcity in the Central African Copperbelt* Dácil Juif, Wageningen University Ewout Frankema, Wageningen University Abstract There is a tight historical connection between endemic labour scarcity and the rise of coercive labour market institutions in former African colonies. This paper explores how mining companies in the Belgian Congo and Northern Rhodesia secured scarce supplies of African labour, by combining coercive labour recruitment practices with considerable investments in living standard improvements. By reconstructing internationally comparable real wages we show that copper mine workers lived at barebones subsistence in the 1910s-1920s, but experienced rapid welfare gains from the mid-1920s onwards, to become among the best paid manual labourers in Sub-Saharan Africa from the 1940s onwards. We investigate how labour stabilization programs raised welfare conditions of mining worker families (e.g. medical care, education, housing quality) in the Congo, and why these welfare programs were more hesitantly adopted in Northern Rhodesia. By showing how solutions to labour scarcity varied across space and time we stress the need for dynamic conceptualizations of colonial institutions, as a counterweight to their oft supposed persistence in the historical economics literature. -

Tangled! Congolese Provincial Elites in a Web of Patronage

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Tangled! Congolese provincial elites in a web of patronage Working paper 64 Lisa Jené and Pierre Englebert January 2019 Written by Lisa Jené and Pierre Englebert SLRC publications present information, analysis and key policy recommendations on issues relating to livelihoods, basic services and social protection in conflict-affected situations. This and other SLRC publications are available from www.securelivelihoods.org. Funded by UK aid from the UK Government, Irish Aid and the EC. Disclaimer: The views presented in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies or represent the views of Irish Aid, the EC, SLRC or our partners. ©SLRC 2018. Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce material from SLRC for their own publications. As copyright holder SLRC requests due acknowledgement. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium Overseas Development Institute (ODI) 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 3817 0031 F +44 (0)20 7922 0399 E [email protected] www.securelivelihoods.org @SLRCtweet Cover photo: Provincial Assembly, Lualaba. Lisa Jené, 2018 (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). B About us The Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) is a global research programme exploring basic services, livelihoods and social protection in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Funded by UK Aid from the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID), with complementary funding from Irish Aid and the European Commission (EC), SLRC was established in 2011 with the aim of strengthening the evidence base and informing policy and practice around livelihoods and services in conflict. -

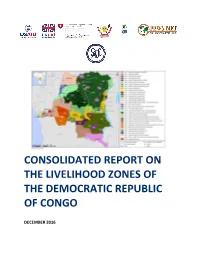

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

A Silent Crisis in Congo: the Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika

CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika Prepared by Geoffroy Groleau, Senior Technical Advisor, Governance Technical Unit The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 920,000 new Bantus and Twas participating in a displacements related to conflict and violence in 2016, surpassed Syria as community 1 meeting held the country generating the largest new population movements. Those during March 2016 in Kabeke, located displacements were the result of enduring violence in North and South in Manono territory Kivu, but also of rapidly escalating conflicts in the Kasaï and Tanganyika in Tanganyika. The meeting was held provinces that continue unabated. In order to promote a better to nominate a Baraza (or peace understanding of the drivers of the silent and neglected crisis in DRC, this committee), a council of elders Conflict Spotlight focuses on the inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu composed of seven and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika. This conflict illustrates how representatives from each marginalization of the Twa minority group due to a combination of limited community. access to resources, exclusion from local decision-making and systematic Photo: Sonia Rolley/RFI discrimination, can result in large-scale violence and displacement. Moreover, this document provides actionable recommendations for conflict transformation and resolution. 1 http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2017/pdfs/2017-GRID-DRC-spotlight.pdf From Harm To Home | Rescue.org CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT ⎯ A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika 2 1. OVERVIEW Since mid-2016, inter-ethnic violence between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups has reached an acute phase, and is now affecting five of the six territories in a province of roughly 2.5 million people. -

Concordant Ages for the Giant Kipushi Base Metal Deposit (DR Congo) from Direct Rb–Sr and Re–Os Dating of Sulfides

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Miner Deposita (2007) 42:791–797 DOI 10.1007/s00126-007-0158-y LETTER Concordant ages for the giant Kipushi base metal deposit (DR Congo) from direct Rb–Sr and Re–Os dating of sulfides Jens Schneider & Frank Melcher & Michael Brauns Received: 30 May 2007 /Accepted: 27 June 2007 / Published online: 24 July 2007 # Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract We report concordant ages of 451.1±6.0 and (upper) crust. The concordant Re–Os and Rb–Sr ages 450.5±3.4 Ma from direct Rb–Sr and Re–Os isochron obtained in this study provide independent proof of the dating, respectively, of ore-stage Zn–Cu–Ge sulfides, geological significance of direct Rb–Sr dating of sphalerite. including sphalerite for the giant carbonate-hosted Kipushi base metal (+Ge) deposit in the Neoproterozoic Lufilian Keywords Kipushi . Base metals . Copperbelt . Congo . Arc, DR Congo. This is the first example of a world-class Rb–Sr isotopes . Re–Os isotopes . Pb isotopes sulfide deposit being directly dated by two independent isotopic methods. The 451 Ma age for Kipushi suggests that the ore-forming solutions did not evolve from metamorphogenic fluids mobilized syntectonically during Introduction the Pan-African-Lufilian orogeny but rather were generated in a Late Ordovician postorogenic, extensional setting. The Precise constraints on the timing of mineralization are of homogeneous Pb isotopic composition of the sulfides fundamental importance in understanding the genesis of indicates that both Cu–Ge- and Zn-rich orebodies of the hydrothermal ore deposits. -

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa: A Threat Assessment Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org OrgAnIzed CrIme And Instability In CenTrAl AFrica A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2011 – 750 October 2011 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa A Threat Assessment Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Acknowledgements This study was undertaken by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA). Researchers Ted Leggett (lead researcher, STAS) Jenna Dawson (STAS) Alexander Yearsley (consultant) Graphic design, mapping support and desktop publishing Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Kristina Kuttnig (STAS) Supervision Sandeep Chawla (Director, DPA) Thibault le Pichon (Chief, STAS) The preparation of this report would not have been possible without the data and information reported by governments to UNODC and other international organizations. UNODC is particularly thankful to govern- ment and law enforcement officials met in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda while undertaking research. Special thanks go to all the UNODC staff members - at headquarters and field offices - who reviewed various sections of this report. The research team also gratefully acknowledges the information, advice and comments provided by a range of officials and experts, including those from the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCO (including the UN Police and JMAC), IPIS, Small Arms Survey, Partnership Africa Canada, the Polé Institute, ITRI and many others. -

A Functional View of Linguistic Meaning

SWAHILI FORUM 22 (2015): vi-viii REVIEW Le swahili de Lubumbashi. Grammaire, textes, lexique [The Swahili from Lubumbashi. Grammar, texts, lexicon]. Aurélia Ferrari, Marcel Kalunga, and Georges Mulumbwa. 2014. Paris: Editions Karthala, 226 pp., ISBN 978-2-8111- 1130-4. Swahili is one of the four national languages of the Democratic Republic of Congo, together with Ciluba, Kikongo and Lingala, spoken by many millions mainly located in the eastern provinces. This interesting volume, appeared amongst the recent contributions to the Karthala series “Dictionnaires et Langues” (Dictionaries and Languages) directed by Henri Tourneux, is devoted 1 to a specific variety of Congolese Swahili, i.e. the Swahili of Lubumbashi , an originally vehicular and hexogen language which, as a result of the colonial language policy (Fabian 1986), has increasingly been spoken among urban residents, principally, but not exclusively, in oral 2 communication and performance , thus entering an ongoing process of vernacularisation and becoming the first language for a part of the population of the Katangese region. The work is a result of the collaboration between Aurélia Ferrari, specialist in emerging African language varieties, presently lecturer at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and two scholars from the DRC, experts in Swahili and Bantu languages, namely Marcel Kalunga, professor at the Universities of Lubumbashi and Kalemie, and Georges Mulumbwa, senior assistant in linguistics at the University of Lubumbashi. The book consists of three parts, the first -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Eortcrepublic Democratic Ftecongo the Of

Democratic Republic of the Congo Democratic Republic of the Congo Main objectives Reintegration and Resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) in cooperation with UNDP, the ssist local authorities to improve the national UN Observer Mission in DRC (MONUC) and the Asystem of asylum; help to increase awareness World Bank. of refugees’ rights within the Government and civil society; promote and facilitate the repatriation in safety and dignity of Rwandan and Burundian refu- Impact gees respectively, as well as the voluntary repatria- tion of Angolan refugees; prepare and organize the • UNHCR signed tripartite agreements for the repa- repatriation of Sudanese and Congolese refugees triation of DRC refugees from the Central African when conditions in their home countries have Republic (CAR) and the Republic of the Congo improved sufficiently; ensure that all refugees who (RoC). Some 2,000 DRC refugees (20 per cent of wish to remain in the Democratic Republic of the the refugee population) returned home from Congo (DRC) enjoy international protection; pro- CAR. Nearly 350 RoC refugees (representing vide international protection and humanitarian some five per cent of the refugee population) assistance to residual groups and urban refugees to were repatriated. help them to become self-reliant; support initiatives for Demobilization, Disarmament, Repatriation, UNHCR Global Report 2004 142 • In total, UNHCR in DRC assisted some 28,000 Working environment people to return home (over 20,000 of them Angolans). From eastern DRC, the Office repatri- ated more than 8,000 Rwandans who were scattered in the provinces of North and South The context Kivu. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic Main objectives Impact • UNHCR provided international protection to some In 2005, UNHCR aimed to strengthen the protection 204,300 refugees in the DRC of whom some 15,200 framework through national capacity building, registra- received humanitarian assistance. tion, and the prevention of and response to sexual and • Some of the 22,400 refugees hosted by the DRC gender-based violence; facilitate the voluntary repatria- were repatriated to their home countries (Angola, tion of Angolan, Burundian, Rwandan, Ugandan and Rwanda and Burundi). Sudanese refugees; provide basic assistance to and • Some 38,900 DRC Congolese refugees returned to locally integrate refugee groups that opt to remain in the the DRC, including 14,500 under UNHCR auspices. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); prepare and UNHCR monitored the situation of at least 32,000 of organize the return and reintegration of DRC Congolese these returnees. refugees into their areas of origin; and support initiatives • With the help of the local authorities, UNHCR con- for demobilization, disarmament, repatriation, reintegra- ducted verification exercises in several refugee tion and resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country locations, which allowed UNHCR to revise its esti- Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) mates of the beneficiary population. in cooperation with the UN peacekeeping mission, • UNHCR continued to assist the National Commission UNDP and the World Bank. for Refugees (CNR) in maintaining its advocacy role, urging local authorities to respect refugee rights. UNHCR Global Report 2005 123 Working environment Recurrent security threats in some regions have put another strain on this situation. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

Kipushi Project Democratic Republic of Congo NI 43-101 Technical Report (Revision 2) September 2012

Kipushi Project Democratic Republic of Congo NI 43-101 Technical Report (Revision 2) September 2012 Prepared for Ivanplats Limited Document Ref.: 984C-R-13 Qualified persons: Victor Kelly, BA, FAusIMM, P Eng. - Geologist Julian Bennett, BSc, FIMMM, C Eng. - Mining engineer David JF Smith CEng – IMC Director of Mining Kipushi Zinc Mine Project Democratic Republic of Congo NI 43-101 Technical Report (Revision 2) FINAL REPORT Page i Table of Contents 1 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 1 2 INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF REFERENCE ............................................................... 5 3 RELIANCE ON OTHER EXPERTS ................................................................................... 6 4 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION ................................................................... 6 4.1 Legal Title ............................................................................................................................ 7 4.1.1 Mineral Property and Title in the DRC ................................................................................ 7 4.1.2 Surface Rights Title ............................................................................................................ 10 4.1.3 Royalties ............................................................................................................................ 10 4.1.4 Environmental Obligations............................................................................................... -

Musebe Artisanal Mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo

Gold baseline study one: Musebe artisanal mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo Gregory Mthembu-Salter, Phuzumoya Consulting About the OECD The OECD is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. About the OECD Due Diligence Guidance The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Due Diligence Guidance) provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is for use by any company potentially sourcing minerals or metals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. It is one of the only international frameworks available to help companies meet their due diligence reporting requirements. About this study This gold baseline study is the first of five studies intended to identify and assess potential traceable “conflict-free” supply chains of artisanally-mined Congolese gold and to identify the challenges to implementation of supply chain due diligence. The study was carried out in Musebe, Haut Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. This study served as background material for the 7th ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in Paris on 26-28 May 2014. It was prepared by Gregory Mthembu-Salter of Phuzumoya Consulting, working as a consultant for the OECD Secretariat.