P.214-223 HOTYD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FUTURE FOLK Wild Up: Is a Modern Music Collective; an Beach Music Festival

About the Artists Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director PRESENTS wild Up: ABOUT THE ORCHESTRA FUTURE FOLK wild Up: is a modern music collective; an Beach Music Festival. They played numerous Music Festival; taught classes on farm sounds, adventurous chamber orchestra; a Los Angeles- programs with the Los Angeles Philharmonic spatial music and John Cage for a thousand based group of musicians committed to creating including the Phil’s Brooklyn Festival, Minimalist middle schoolers; played solo shows at The Getty, visceral, thought-provoking happenings. wild Up Jukebox Festival, Next on Grand Festival, and a celebrated John Adams 70th birthday with a show Future Folk Personnel Program believes that music is a catalyst for shared experiences, twelve hour festival of Los Angeles new music called “Adams, punk rock and player piano music” ERIN MCKIBBEN, Flute and that a concert venue is a place to challenge, hosted by the LA Phil at Walt Disney Concert Hall at VPAC . ART JARVINEN excite and ignite a community of listeners. called: noon to midnight. They started a multi- BRIAN WALSH, Clarinets Endless Bummer year education partnership with the Colburn While the group is part of the fabric of classical ARCHIE CAREY, wild Up has been called “Best in Classical Music School, taught Creativity and Consciousness at music in L.A., wild Up also embraces indie music Bassoon / Amplified Bassoon ROUNTREE/KALLMYER/CAREY 2015” and “…a raucous, grungy, irresistibly Bard’s Longy School, led composition classes with collaborations. The group has an album on for La Monte Young exuberant…fun-loving, exceptionally virtuosic the American Composers Forum and American Bedroom Community Records with Bjork’s choir ALLEN FOGLE, Horn family” by Zachary Woolfe of the New York Times, Composers Orchestra, created a new opera Graduale Nobili, vocalist Jodie Landau, and JONAH LEVY, Trumpet MOONDOG “Searing. -

Song Lyrics ©Marshall Mitchell All Rights Reserved

You Don’t Know - Song Lyrics ©Marshall Mitchell All Rights Reserved Freckled Face Girl - Marshall Mitchell © All Rights Reserved A freckled face girl in the front row of my class Headin’ Outta Wichita - Harvey Toalson/Marshall Mitchell On the playground she runs way too fast © All Rights Reserved And I can’t catch her so I can let her know I think she is pretty and I love her so Headin’ outta Wichita; we’re headed into Little Rock tonight And we could’ve had a bigger crowd but I think the band was sounding pretty tight She has pigtails and ribbons in her hair With three long weeks on this road there ain’t nothing left to do, you just listen to the radio When she smiles my heart jumps into the air And your mind keeps a’reachin’ back to find that old flat land you have the nerve to call your home And all through high school I wanted her to know That I thought she was pretty and I loved her so Now, you can’t take time setting up because before you know it’s time for you to play And you give until you’re giving blood then you realize they ain’t a’listenin’ anyway I could yell it in assembly And then you tell yourself that it can’t get worse and it does, and all you can think about is breaking down I could write it on the wall And then you find yourself back on the road following a dotted line to another town Because when I am around her I just cannot seem to speak at all I wanna see a starlit night and I wanna hold my baby tight again While in college I saw her now and then And I’m really tired of this grind and I’d sure like to see the face -

Julius Eastman: the Sonority of Blackness Otherwise

Julius Eastman: The Sonority of Blackness Otherwise Isaac Alexandre Jean-Francois The composer and singer Julius Dunbar Eastman (1940-1990) was a dy- namic polymath whose skill seemed to ebb and flow through antagonism, exception, and isolation. In pushing boundaries and taking risks, Eastman encountered difficulty and rejection in part due to his provocative genius. He was born in New York City, but soon after, his mother Frances felt that the city was unsafe and relocated Julius and his brother Gerry to Ithaca, New York.1 This early moment of movement in Eastman’s life is significant because of the ways in which flight operated as a constitutive feature in his own experience. Movement to a “safer” place, especially to a predomi- nantly white area of New York, made it more difficult for Eastman to ex- ist—to breathe. The movement from a more diverse city space to a safer home environ- ment made it easier for Eastman to take private lessons in classical piano but made it more complicated for him to find embodied identification with other black or queer people. 2 Movement, and attention to the sonic remnants of gesture and flight, are part of an expansive history of black people and journey. It remains dif- ficult for a black person to occupy the static position of composer (as op- posed to vocalist or performer) in the discipline of classical music.3 In this vein, Eastman was often recognized and accepted in performance spaces as a vocalist or pianist, but not a composer.4 George Walker, the Pulitzer- Prize winning composer and performer, shares a poignant reflection on the troubled status of race and classical music reception: In 1987 he stated, “I’ve benefited from being a Black composer in the sense that when there are symposiums given of music by Black composers, I would get perfor- mances by orchestras that otherwise would not have done the works. -

SMYC 2013 CD Booklet

SPECIAL MULTISTAKE YOUTH CONFERENCE 2013 MUSIC SOUNDTRACK Audio CD_Booklet.indd 1 10/18/2013 9:04:08 AM Stand Chorus Chorus: Joy of Life Singer: Megan Sackett No, I can’t say that I know for certain, but, Singers: Savanna Liechty & Hayden Gillies Every choice, every step, I’m feelin’ somethin’ deep inside my heart Morning sun fill the earth, every moment, I wanna say that I know for certain, Sunlight breaking through the shadows fill the shadows, point my course, set my path but for now it’s a good start. stand lighting all we see fill my soul with light. make me ready. taking in each single moment Sacred light, holy house, I’ve been trying things out a bit, with the air we breath Steady flame, steady guide, loving Father, wanting to know what’s real still so much that lies before us steady voice of peace bind my heart, fill my life I don’t know what will come of it but still so much within our reach lead me through the night. with this promise to stand… if I keep it up I will. of life joy Chorus: Won’t give in, won’t give up And be not moved, together I know there’s someone who after all I can do Every day won’t give out at all Stand makes it all alright brings another moment ‘til my heart is right. In a holy place Then I hear a voice that whispers to me every time Stand… Oh Stand that I’ve known it all my life. -

Project VIP Spring2020 Manuscript

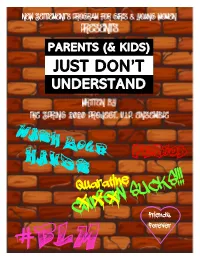

PARENTS (& KIDS) JUST DON’T UNDERSTAND PERIOD Friends Forever #BLM PARENTS (& KIDS) JUST DON’T UNDERSTAND Table of Contents I. Ensemble Photos pg 2 II. Directors’ Note pg 3 III. Scripts: 1. Some Things We Wish Our Parents Would Have Told Us pg 4 2. Period Piece pg 5 3. Sister Sister pg 10 4. What I Wish I could Tell You pg 12 5. Wear What I Want pg 13 6. Party At A Friend’s pg 19 7. Things Heard During Covid-19 Quarantine pg 23 Written by the Ensemble: Jendayi Benjamin, Sariya Western Boyd, Aniyah Campos, Ashanti Campos, Shea Davis, Deshante Deberry, Atseda Johnson, Annalise Rios Mercado, Jaslene Rios Mercado, Tia Sledge & Nakayla Teagle 1 Dear Aniyah, Annalise, Ashante, Atseda, Deshante, Jaslene, Jendayi, Nakayla, Sariya, Shea & Tia: What an interesting semester we have had! We came in talking about parents and all the craziness we had to endure with them … remember watching Will Smith’s video for Parents Just Don’t Understand, and then the corny (but funny) song “Kids” from Bye Bye Byrdie? And improvising (hilarious) inner voice/outer voice conversations? And then our world turned upside down. We’ve never had a semester like this where so much of our work was completed online. No rehearsals, no more theatre games, no more seeing each other in person. Yet despite all this we came up with some great scripts and poems to show how parent and child relationships work in 2020. We loved the energy you brought to the group. Thank you for all your hard work in class and online. -

I Wanna Go Home by David Catrow (Illustrator) and Karen Kaufman Orloff (Author)

A Choose to Read Ohio Toolkit I Wanna Go Home By David Catrow (illustrator) and Karen Kaufman Orloff (author) Use this toolkit to plan library About the Book programs as well as Alex is not happy about being sent to activities for the his grandparents’ retirement daycare, community while his parents go on a classroom, or fabulous vacation. What could be family. worse than tagging along to Grandma’s boring bridge game or Meet Ohio illustrator enduring the sight of Grandpa’s David Catrow and dentures? Hudson Valley New York author Karen But as the week goes on, Alex’s Kaufman Orloff. desperate emails to his parents turn into stories about ice cream before Read, write, sing, dinner and stickball with Grandpa. and play together Before he knows it, Alex has made a Permission to use book jacket image and book description granted by Penguin Random House. with engaging surprising discovery: grandparents are extensions inspired way cooler than he thought! by the adventures of Alex and his G. P. Putnam’s Sons/Penguin Group (USA), 2014. siblings and ISBN 9780399254079. Ages 5-8. 32 pages. grandparents. Leveled Reading: AR Points 0.5. ATOS Book Level 3.3. AD610L Lexile penguin.com/book/i-wanna-go-home-by-karen-kaufman-orloff-illustrated-by-david Explore fun -catrow/9780399254079 activities that align with Ohio’s Learning Available as an ebook through the Ohio Digital Library: ohiodigitallibrary.com Standards for kindergarten through grade 3. I Wanna Go Home is the third in the I Wanna series of books about Alex, his siblings, and his fun-loving family and pets. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1812

S1812 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 27, 2014 and Mr. Somphone’s safe return to his years has grown to be a mainstay of public service in many other venues family, his disappearance is still unex- our regional and State agricultural and that the seventh generation plained. economy. Allenholm Farm will continue to A respected member of the develop- In 1870, Ray Allen’s great-grand- thrive under his leadership. ment community, Mr. Somphone has father purchased the current farm, Marcelle and I think of Ray and Pam lived and worked for many years in marking the beginning of a family as very special friends and cherished Laos and his efforts to strengthen Lao- farming tradition on lovely Grand Isle, Vermonters. tian civil society are well documented. VT. Today, Ray and his wife Pam run f the Allenholm Farm with the help of The circumstances of his disappearance RECOGNIZING SUNDY BEST are mysterious, and, given his high their children, grandchildren, and now profile, more than troubling. Further- great-grandchildren. Mr. MCCONNELL. Mr. President, I more, the lack of effort on the part of The chain of islands running up the rise today to recognize an exception- the Laotian government to investigate center of Lake Champlain was once ally talented country music duo from what has been described by many inter- home to more than 100 commercial my home State of Kentucky. Kris national observers as a forced dis- apple orchards. Today there are fewer, Bentley and Nick Jamerson have vault- appearance is deeply disappointing. but the Allen’s have thrived through ed their band, Sundy Best, from the Mr. -

Kidtribe Fitness Par-Tay!

www.kidtribe.com KidTribe’s “Hooper-Size” CD “What Up? Warm Up!” / KidTribe Theme / Hoop Party / Hooper-Size Me / Hoop-Hop-Don’t-Stop / Hooper’s Delight / Peace Out! Warm-Up What Up? Warm Up – KidTribe / Start the Commotion – The Wiseguys / Put Your Hands Up In the Air (radio edit) - Danzel Don’t Stop the Party, I Gotta Feeling, Let’s Get It Started – Black-Eyed Peas / Right Here Right Now – Fatboy Slim I Like to Move It – Chingy (Please get from “Madagascar” soundtrack, otherwise there’s a slight content issue – use of the word “sexy” in one part – easy to cheer over it though.) /Get the Party Started – Pink / Cooler Than Me – Mike Posner Free-Style / Skill Building (current hip-hop / pop music) – make sure ALL are CLEAN or RADIO EDITS All Grades (rated G / PG): o Anything & everything by Michael Jackson, Lady Gaga, Step Up Soundtracks o Gangnam Style - Psi o Party Rock Anthem - LMFAO o Chasing the Sun, Wish You Were Here – The Wanted, o Scream & Shout (RADIO EDIT)- Will. I.Am o Don’t Stop the Party, I Gotta Feeling, Rock That Body, Boom Boom Pow (RADIO EDIT)– Black Eyed Peas o We Found Love, Where Have You Been, Only Girl, Disturbia, Umbrella, Pon de Replay, SOS – Rihanna o All Around the World, Beauty and the Beat (Justin Bieber) o Firework, California Girls, ET – Katie Perry o Good Time – Owl City o Moves Like Jagger, Pay Phone, one More Night – Maroon 5 o Good Feeling, Wild Ones, Where Them Girls At, Club Can’t Handle Me, Right Round, In the Ayer, Sugar – Flo Rida o Live While We’re Young – One Direction o Starships – Nicki Minage -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

The Musical Worlds of Julius Eastman Ellie M

9 “Diving into the earth”: the musical worlds of Julius Eastman ellie m. hisama In her book The Infinite Line: Re-making Art after Modernism, Briony Fer considers the dramatic changes to “the map of art” in the 1950s and characterizes the transition away from modernism not as a negation, but as a positive reconfiguration.1 In examining works from the 1950s and 1960s by visual artists including Piero Manzoni, Eva Hesse, Dan Flavin, Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, and Louise Bourgeois, Fer suggests that after a modernist aesthetic was exhausted by mid-century, there emerged “strategies of remaking art through repetition,” with a shift from a collage aesthetic to a serial one; by “serial,” she means “a number of connected elements with a common strand linking them together, often repetitively, often in succession.”2 Although Fer’s use of the term “serial” in visual art differs from that typically employed in discussions about music, her fundamental claim I would like to thank Nancy Nuzzo, former Director of the Music Library and Special Collections at the University at Buffalo, and John Bewley, Archivist at the Music Library, University at Buffalo, for their kind research assistance; and Mary Jane Leach and Renée Levine Packer for sharing their work on Julius Eastman. Portions of this essay were presented as invited colloquia at Cornell University, the University of Washington, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Peabody Conservatory of Music, the Eastman School of Music, Stanford University, and the University of California, Berkeley; as a conference paper at the annual meeting of the Society for American Music, Denver (2009), and the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, Kansas City (2009); and as a keynote address at the Michigan Interdisciplinary Music Society, Ann Arbor (2011). -

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co.