Prelude: of Dance & the Extraordinary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Standards- Based Creativity in the Arts

Teaching Standards-based Creativity in the Arts Issued by Office of Academic Standards South Carolina Department of Education Jim Rex State Superintendent of Education 2007 1 Table of Contents CONTRIBUTORS ................................................................................. 3 WHY CREATIVITY? ............................................................................. 5 CULTIVATING CREATIVITY IN ARTS EDUCATION: MYTHS, MISCONCEPTIONS, AND PRACTICAL PROCEDURES………………………..7 DANCE: .......................................................................................... 100 GRADES PREK-K ............................................................................... 101 GRADES 1-2 .................................................................................... 111 GRADES 3-5 .................................................................................... 122 GRADES 6-8 .................................................................................... 139 GRADES 9-12 .................................................................................. 162 GRADES 9-12 ADVANCED .................................................................... 186 DANCE CREATIVITY RESOURCE LIST ........................................................ 208 MUSIC ............................................................................................ 213 MUSIC: GENERAL ............................................................................. 214 GRADES PREK-K .............................................................................. -

NEO-Orientalisms UGLY WOMEN and the PARISIAN

NEO-ORIENTALISMs UGLY WOMEN AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE, 1905 - 1908 By ELIZABETH GAIL KIRK B.F.A., University of Manitoba, 1982 B.A., University of Manitoba, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA . October 1988 <£> Elizabeth Gail Kirk, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date October, 1988 DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT The Neo-Orientalism of Matisse's The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, both of 1907, exists in the similarity of the extreme distortion of the female form and defines the different meanings attached to these "ugly" women relative to distinctive notions of erotic and exotic imagery. To understand Neo-Orientalism, that is, 19th century Orientalist concepts which were filtered through Primitivism in the 20th century, the racial, sexual and class antagonisms of the period, which not only influenced attitudes towards erotic and exotic imagery, but also defined and categorized humanity, must be considered in their historical context. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications a Finding Aid

The Mary Baker Eddy Library Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications a finding aid mbelibrary.org [email protected] 200 Massachusetts Ave. Boston, MA 02115 617-450-7218 Collection Description Collection #: 11 MBE Collection Title: Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications Creator: Eddy, Mary Baker Inclusive Dates: 1856-1910, 1912 Extent: 15.25 __LF Provenance: Transferred from Mary Baker Eddy’s last home at Chestnut Hill (400 Beacon St.) on the following dates: August 26, 1932, June 1938, May 7, 1951, and April 1964. Copyright Materials in the collection are subject to applicable copyright laws. Restrictions: Scope and Content Note Mary Baker Eddy Pamphlets and Serial Publications consists of over 600 items chiefly from Mary Baker Eddy's files from her last residence at Chestnut Hill. All of the items in the collection were published during Eddy’s lifetime except "The Children’s Star" dated October 1912 (PE00030) and "A Funeral Sermon: Occasioned by the death of Mr. George Baker," 1679 (PE00109). Many of the items were annotated, marked, and requested by Eddy to be saved (see PE00055.033, PE00185-PE00189, PE00058.127). The collection consists of two series: Series I, Pamphlets and Series II, Serial Publications. Series I, Pamphlets, consists mostly of the writings of Mary Baker Eddy as small leaflets or booklets. The series also consists of writings by persons significant to the history of Christian Science (Edward A. Kimball, Bliss Knapp, Septimus J. Hanna, etc.). Some of the pamphlets were never published such as "Why is it?" by Mary Baker Eddy (PE00262). Pamphlets also include "Christ My Refuge" sheet music (PE00032) and a Science and Health advertisement (PE00220). -

Numero 24 Marzo-Aprile 2015 BIMESTRALE - POSTE ITALIANE S.P.A

ISSN 2280-8817 anno v numero 24 marzo-aprile 2015 BIMESTRALE - POSTE ITALIANE S.P.A. SPED. IN A.P. 70% - ROMA - COPIA EURO 0,001 - COPIA 70% - ROMA A.P. SPED. IN S.P.A. BIMESTRALE - POSTE ITALIANE I PUBBLICI DEI MUSEI NUMERI E GRAFICI ARTE & LETTERATURA LOMBARDIA, MILANO, BERGAMO QUATTRO MESI A NEW YORK IL MERCATO DELLE GALLERIE DAVID FOSTER WALLACE MAPPE E CONSIGLI DI VIAGGIO CITTÀ-STATO: REPORTAGE TOTO COTUGNO BANCHE & ARTE DA SINGAPORE A MALTA UNA FOTO CONCETTUALE UBS, ART BASEL E LA GAM àncora di salvezza sul dissesto della cultura nella Capitale del Paese – dissesto di cui incessantemente parliamo da anni – potrebbe in maniera inaspettata giungere dal Vaticano. L’annuncio del Giubileo Straordinario da parte di Papa Bergoglio schiude opportunità impensabili per una città che ha totalmente perduto, dal punto di vista della programmazione museale, il treno di Expo 2015, ma che ora ha la chance di prendere quello del Giubileo 2016. L’allure del cambio di millennio non c’è, i soldi che vi furono allora non ci sono (3mila miliardi e mezzo di TONELLI lire), non c’è neppure un papa dallo spessore di Giovanni Paolo II sebbene Francesco abbia un seguito non indifferente. Quel che potrebbe esserci è l’afflusso di pubblico da tutto il mondo. Anzi la quantità di pellegrini e di turisti che utilizzeranno il Giubileo come scusa per visitare la Città Eterna potrebbe aumentare perché MASSIMILIANO la propensione a spostarsi è enormemente aumentata rispetto al 2000. Ci sono le low cost e all’epoca non c’erano. Ci sono i treni veloci e allora non c’erano. -

"The Dance of the Future"

Chap 1 Isadora Duncan THE DANCER OF THE FUTURE I HE MOVEMENT OF WAVES, of winds, of the earth is ever in the T same lasting harmony. V·le do not stand on the beach and inquire of th€ E>t:ea:n what was its movement in the past and what will be its movement in the future. We realize that the movement peculiar to its nature is eternal to its nature. The movement of the free animals and birds remains always in correspondence to their nature, the necessities and wants of that nature, and its correspond ence to the earth nature. It is only when you put free animals under ~~restr iction s that the"y lose the power-or moving lnlla rr'n o~y with nature, and adopt a movement expressive of the restncflons placed about thel!l. · . ------~- ,. So it has been with civili zed man. The movements of the savage, who lived in freedom in constant touch with Nature, were unrestricted, natural and beautiful. Only the movements of the r:ilkeJ..J22.9.y_ca~ be p:rfectl): 12_a~al. Man, arrived at the end of civilization, will have to return to nakedness, not to tl1e uncon scious nakedness of the savage, but to the conscious and acknow ledged nakedness of the mature Man,· whose body will be th~ harmonious expression of his spiritual being And the movements of tl1is Man will be natural and beautiful like those of the free animals. The movement of the universe concentrating in an individual becomes what is termed the will; for example, tl1e movement of the earth, being the concentration of surrounding· forces, gives to the earth its individuality, its will of movement. -

775M Eh 7¢Ate¢

C opyright 1 962 R evision C o pyright 1 96 3 by Arthur C orey 5 X 5 7 4 5 £ 5 7 Prin ted in Th e Un ited States o f America MORE CLASS N OTES The L os Gatos - Saratoga class taught at my home, Casita Cresta, accommodated but a minor fraction of the applicants . Thus it seemed a happy fortuity when substantial notes taken of that an aly tical exploration of applied metaphysics were made available to me afterward . Their publication in 1956 n o t only provided review materials for those who came from various parts of the field for the n e eve t, but it enabled the absent stud nts to share, in . at least some measure, in the undertaking Now, with this greatly enlarged edition of the orig inal pamphlet it is possible to include additional material found useful by the many who attended the San Francisco class later on . The present paper does not purport to be a com n o r prehensive restatement of either course, can it be regarded as a rounded presentation o f even the bare essentials . Nevertheless, however fragmentary it may be it does cover some of the cardinal points made, points which the students generally felt should be made a part of the permanent record for s u continuing t dy . It is a commonplace that class notes are seldom r r ve y accu ate . That does not mean they are worth less . On the contrary, every veteran Scientist can o ut testify, as Bicknell Young pointed to his pupils, that such n otes can on occasion prove priceless . -

A History of the New Thought Movement

RY OF THE r-lT MOVEMEN1 DRESSER I Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO by Victoria College A HISTORY OF THE NEW THOUGHT MOVEMENT BY HORATIO W. DRESSER AUTHOR OF "THE POWER OF SILENCE," * 'HANDBOOK OF THE NEW THOUGHT," "THE SPIRIT OF THE NEW THOUGHT," ETC. NEW YORK THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY PUBLISHERS JUL COPYRIGHT, 1919. BY THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY PREFACE FOR several years there has been a demand for a history of the liberal wing of the mental-healing movement known as the "New Thought." This demand is partly due to the fact that the move- ment is now well organized, with international headquarters in Washington, D. C., hence there is a desire to bring its leading principles together and see in their in to inter- them unity ; and part est in the pioneers out of whose practice the present methods and teachings have grown. The latter interest is particularly promising since the pioneers still have a message for us. Then, too, we are more interested in these days in trac- ing the connection between the ideas which con- cern us most and the new age out of which they have sprung. We realize more and more clearly that this is indeed a new age. Hence we are in- creasingly eager to interpret the tendencies of thought which express the age at its best. In order to meet this desire for a history of the New Thought, Mr. James A. Edgerton, president of the International New Thought Alliance, decided in 1916 to undertake the work. -

Officially.Approves Requirements .Election Resolution

.,\ ~;. \ All The 'News ~~l~~ Of All , , ._~"t. The Pointes ,. ~very Thursday Morning VOLUME. I5-NO~ 15 Fully Paid Circulation \ U~ADL~ES 01 I,'J. ~ .Board.of Education Ask $30,000 WEEK -. ,_., .: I. " • # For Budget As C;ompiled by Ih. OffIcIally.Approves Requirements Gross. Point. News • Tliursday, April 8 Total' of $93,500 Needed to SABURO KURUSU, who was .Election Resolution .' Maintain and Operate . negotiating peace with the United Center Next Year States when Japan dropped her bombs on Pearl Harbor on De- ~. I PI F N F S' I AI 'The Grosse Pointe War cember. 7, 1951, is dead at the Organizationa ans. ~r ewer r y choo so Memorial AssociatiDn's annual age of 69. He had long. been re- Adopted; Over-crowded Condition at Pierce campaign for funds to. main .. ga~ded. as pro-Western, and all along insisted he had no advanced Ju..n.ior. High Brings. Action tain and operate the Center in knowledge of the imperials staff's ------ Lake Shore road begins today, intention to strike at Pearl Hat;- At its regular monthly meeting on April 7 the Board df April 15. It will 'continue until bor. Education officially adopted a resolutiDn setting fort~ the pro- Memorial Day. Residents are He was never brought to trial' , posals which will be submitted to ,the voters. at the Animal being asked to contribute .s a war criminal, ,but was 'ba.l- School Ele'ction on June 14. The resolution was formally $30,000, . ned from holding public office adopte'd following a series of regular and special board meet- The' amount established as the by the Allied occupation, ings in which many c~tizen delegations strongly urged the goal of this year's drive is $5,O~ • • • Board to take immediate steps to alleviate se\\eral serious more than the $25,000sought last Friday, Aprll 9 h 1 bl '" I year. -

Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline

Guiding Document: Humanities Course Outline Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline The Humanities To study humanities is to look at humankind’s cultural legacy-the sum total of the significant ideas and achievements handed down from generation to generation. They are not frivolous social ornaments, but rather integral forms of a culture’s values, ambitions and beliefs. UNIT ONE-ENLIGHTENMENT AND COMPARATIVE GOVERNMENTS (18th Century) HISTORY: Types of Governments/Economies, Scientific Revolution, The Philosophes, The Enlightenment and Enlightenment Thinkers (Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Jefferson, Smith, Beccaria, Rousseau, Franklin, Wollstonecraft, Hidalgo, Bolivar), Comparing Documents (English Bill of Rights, A Declaration of the Rights of Man, Declaration of Independence, US Bill of Rights), French Revolution, French Revolution Film, Congress of Vienna, American Revolution, Latin American Revolutions, Napoleonic Wars, Waterloo Film LITERATURE: Lord of the Flies by William Golding (summer readng), Julius Caesar by Shakespeare (thematic connection), Julius Caesar Film, Neoclassicism (Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedie excerpt, Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man”), Satire (Oliver Goldsmith’s Citizen of the World excerpt, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels excerpt), Birth of Modern Novel (Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe excerpt), Musician Bios PHILOSOPHY: Rene Descartes (father of philosophy--prior to time period), Philosophes ARCHITECTURE: Rococo, Neoclassical (Jacques-Germain Soufflot’s Pantheon, Jean- Francois Chalgrin’s Arch de Triomphe) -

Team Gallery, Inc., 83 Grand St New York, Ny 10013 Tel. 212.279.9219 Fax

www.teamgal.com For Immediate Release: Sam McKinniss Daisy Chain 07 January through 25 February 2018 306 Windward Avenue Team (bungalow) is pleased to announce a show of work by New York-based artist Sam McKinniss. The show, entitled “Daisy Chain”, will run from 07 January through 25 February 2018. The Bungalow is located at 306 Windward Avenue in Venice Beach, California. “I was meant to know the plot, but all I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no ‘meaning’ beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting-room experience.” -- Joan Didion, The White Album, 1979 McKinniss has made a grouping of nine new paintings to be exhibited together under the title “Daisy Chain”. The city of Los Angeles inspired the choice of subjects, although a narrative of innocence and its destruction is the real thread here. The paintings, all intimately scaled, depict movie stars, pop singers, animals, book illustrations, landscapes. These images stitch themselves together, revealing a national obsession with creating, then desecrating, icons of purity. Behind these beatific paintings – a fantasia of greeting card images – lurk cults, suicide, murder and drug addiction. In selecting the images that make up this exhibition, McKinniss has touched upon popular and mass culture, middle and high-brow. In the degree to which a visitor recognizes one or more of these subjects, a shortcut is forged between the painter and his audience, a shortcut that bypasses irony, erases distance and eases the triggering of emotional effects. McKinniss’s choices both limit his audience — “I don’t like Drew Barrymore.” “Who is A$AP Rocky?” — while privileging those who remain, validating the viewer’s own cultural knowledge and enveloping them in a memory of love — “That’s Whitney Houston when she sang the ‘Star Spangled Banner’”. -

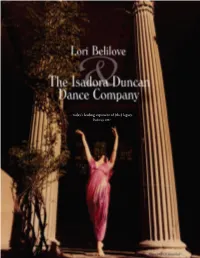

Today's Leading Exponent of (The) Legacy

... today’s leading exponent of (the) legacy. Backstage 2007 THE DANCER OF THE FUTURE will be one whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of that soul will have become the movement of the human body. The dancer will not belong to a nation but to all humanity. She will not dance in the form of nymph, nor fairy, nor coquette, but in the form of woman in her greatest and purest expression. From all parts of her body shall shine radiant intelligence, bringing to the world the message of the aspirations of thousands of women. She shall dance the freedom of women – with the highest intelligence in the freest body. What speaks to me is that Isadora Duncan was inspired foremost by a passion for life, for living soulfully in the moment. ISADORA DUNCAN LORI BELILOVE Table of Contents History, Vision, and Overview 6 The Three Wings of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation I. The Performing Company 8 II. The School 12 ISADORA DUNCAN DANCE FOUNDATION is a 501(C)(3) non-profit organization III. The Historical Archive 16 recognized by the New York State Charities Bureau. Who Was Isadora Duncan? 18 141 West 26th Street, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10001-6800 Who is Lori Belilove? 26 212-691-5040 www.isadoraduncan.org An Interview 28 © All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation. Conceived by James Richard Belilove. Prepared and compiled by Chantal D’Aulnis. Interviews with Lori Belilove based on published articles in Smithsonian, Dance Magazine, The New Yorker, Dance Teacher Now, Dancer Magazine, Brazil Associated Press, and Dance Australia.