Zambia 2017 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Brief Zambia 50/50

50/50 POLICY BRIEF ZAMBIA MARCH 2020 Key facts This country policy brief sets out key issues and options for the increased represen- tation of women in politics in Zambia following the 2016 elections in which women's political representation at national and local level is still far below the 50% espoused in various commitments made by Zambia. The issue is of critical importance given the fact that: • The country's next elections are in 2021. • Unlike many ESARO countries, there is no provision at all for Temporary Special Measures (TMS) to promote women's political participation at any level of governance in Zambia. • The Constitution Amendment Bill of 2019 presents an opportunity to introduce changes. • There is considerable traction in Zambia around electoral reform at national, A differently abled voter casting her vote at Loto Primary School in Mwense District. though not local level. Photo: Electoral Commission of Zambia Last No of seats/ No of % of election/ Next Electoral system candidates/ women women announcement elections appointments elected elected Local government 2016 2021 FPTP 1455 132 9% House of Assembly 2016 2021 FPTP 167 30 18% Presidential elections 2016 2021 FPTP 16 1 6% Cabinet 2016 2021 FPTP 32 8 25% 1 Domestication: The provisions on women's political Barriers to women's political participation have been domesticated through participation the Gender Equality Act (see below); however these provisions are still far from being realised in reality. Zambian women face a multitude of formal and informal barriers to political participation. Despite National Policy Frameworks: Zambia's National the appointment of women to key decision- Gender Policy (NGP) states that: “Women's parti- making positions such as Vice-President, Chief cipation in decision-making has been identified Justice, Head of the Anti-Corruption Commission, as critical to sustainable development. -

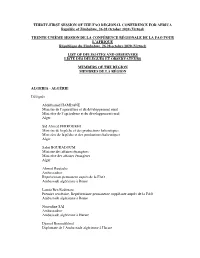

List of Delegates and Observers Liste Des Délégués Et Observateurs

THIRTY-FIRST SESSION OF THE FAO REGIONAL CONFERENCE FOR AFRICA Republic of Zimbabwe, 26-28 October 2020 (Virtual) TRENTE-UNIÈME SESSION DE LA CONFÉRENCE RÉGIONALE DE LA FAO POUR L’AFRIQUE République du Zimbabwe, 26-28 octobre 2020 (Virtuel) LIST OF DELEGATES AND OBSERVERS LISTE DES DÉLÉGUÉS ET OBSERVATEURS MEMBERS OF THE REGION MEMBRES DE LA RÉGION ALGERIA - ALGÉRIE Délégués Abdelhamid HAMDANE Ministre de l’agriculture et du développement rural Ministère de l’agriculture et du développement rural Alger Sid Ahmed FERROUKHI Ministre de la pêche et des productions halieutiques Ministère de la pêche et des productions halieutiques Alger Sabri BOUKADOUM Ministre des affaires étrangères Ministère des affaires étrangères Alger Ahmed Boutache Ambassadeur Représentant permanent auprès de la FAO Ambassade algérienne à Rome Lamia Ben Redouane Premier secrétaire, Représentante permanente suppléante auprès de la FAO Ambassade algérienne à Rome Nacerdine SAI Ambassadeur Ambassade algérienne à Harare Djamel Benmakhlouf Diplomate de l’Ambassade algérienne à Harare 31 ARC SALAH CHOUAKI Directeur central Ministère de l'agriculture et du développement rural Alger Mimi HADJARI Docteur vétérinaire principale Ministère de la pêche et des productions halieutiques Alger Meriem ASSAMEUR Ingénieur d'État des pêches Ministère de la pêche et des productions halieutiques Alger Achwak Bourorga Conservateur divisionnaire des forêts Direction générale des Forêts Alger Karima Ghoul Chargée d'études et de synthèse Ministère de la pêche et des productions halieutiques -

Linking Women with Agribusiness in Zambia: Corporate Social

Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURE GLOBAL PRACTICE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized LINKING WOMEN WITH AGRIBUSINESS IN ZAMBIA CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY, CREATING Public Disclosure Authorized SHARED VALUE, AND HUMAN RIGHTS APPROACHES Pamela White, Gerry Finnegan, Eija Pehu, Pirkko Poutiainen, and Marialena Vyzaki WORLD BANK GROUP REPORT NUMBER 97510-ZM JUNE 2015 Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURE GLOBAL PRACTICE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PAPER LINKING WOMEN WITH AGRIBUSINESS IN ZAMBIA Corporate Social Responsibility, Creating Shared Value, and Human Rights Approaches Pamela White, Gerry Finnegan, Eija Pehu, Pirkko Poutiainen, and Marialena Vyzaki © 2015 World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org Email: [email protected] All rights reserved This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Executive Directors of World Bank Group or the governments they represent. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of World Bank Group concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. World Bank Group encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. -

National Tripartite Dialogue on Maternity Protection

National Tripartite Dialogue on Maternity Protection Dates: 27-28 March 2013 Venue: New Government Complex Main Theme: Toward ratification of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) in Zambia Day 1-Wednesday 27th March 2013 Time Session Moderator: Ms. Mable Mung’omba 08:00-08:25 Arrival and registration of participants, Senior Government Officials, invited Guests Secretariat - Government of Zambia 08:25 Arrival Guest of Honour 08:25 – 08:30 National Anthem and Prayer Opening Session 08:30-10:00 Remarks by the International Labour Organization(ILO) - Mr. Martin Clemmenson, Director ILO (Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique) Remarks by Zambia Federation of Employers (ZFE) - Mr. Alfred Masupha, President Remarks by Federation of Free Trade Unions of Zambia (FFTUZ) - Ms. Joyce Nonde Simukoko, President Remarks by Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) - Mr. Leonard Hikaumba, President ENTERTAINMENT - Drama Remarks by Minister of Labour and Social Security - Hon. Fackson Shamenda Minister of Gender and Child development - Hon. Inonge Wina Key Note Address by Guest of Honour, Dr. Christine KasebaSata (Presentation of Maternity Protection Poster “Every Woman Counts”) 10:00 – 10:30 Photo Opportunity-Refreshments 10:30–11.30 1. Maternity Protection Commitments Zambia’s national, international and regional commitments on Gender and Maternity Protection Ministry of Gender and Child Development 2. Legal and policy frameworks governing the implementation of MaternityProtection in Zambia National Gender Policy Ministry of Gender and Child Development Zambian Labour Laws/ OSH (Employment Act, Minimum Wage Act, etc…) Ministry of Labour and Social Security Maternal Health Policy Ministry of Community Development 11:30-12:00 Q&A Session 12:00 – 12:15 Key elements of maternity protection in Conventions Nos 103, 183 and accompanying Ms. -

UN Women, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, with the Support of the United Nations Regional Commissions

Directory of NATIONAL MECHANISMS for Gender Equality July 2013 6 This page is intentionally left blank 7 Directory of NATIONAL MECHANISMS for Gender Equality July 2013 The Directory of National Mechanisms for Gender Equality is maintained by UN Women, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, with the support of the United Nations Regional Commissions. In order to ensure that the information in the Directory is as comprehensive and accurate as possible, Governments are kindly invited to provide relevant information corrections and/or additions regarding their national machineries to: UN Women United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women New York, NY 10017 Phone: (646) 781-4426 E-mail: [email protected] National Mechanism Country: Name: Address: Telephone: FAX: E-Mail: URL: Head of National Mechanism Name: Title: Appointed by: 8 Secondary data entry form - National mechanisms for gender equality* Country: Name of mechanism: Address: Telephone: FAX: Email: URL: Head of mechanism Name: Title: * For purposes of the Directory, the term ‘national mechanisms for gender equality’ is understood to include those bodies and institutions within different branches of the State (legislative, executive and judicial branches) as well as independent, accountability and advisory bodies that, together, are recognized as ‘national mechanisms for gender equality’ by all stakeholders. They may include, but not be limited to: The national mechanisms for the advancement of women within Government (e.g. a Ministry, Department, or Office. See paragraph 201 of the Beijing Platform for Action) inter-ministerial bodies (e.g. task forces/working groups/commissions or similar arrangements) advisory/consultative bodies, with multi-stakeholder participation gender equality ombud gender equality observatory Parliamentary committee 9 This page is intentionally left blank 10 Afghanistan Women's Affairs Address Park Road Name Mrs. -

Country Gender Profile: Zambia Final Report

Country Gender Profile: Zambia Final Report March 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Japan Development Service Co., Ltd. (JDS) EI JR 16-098 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) commissioned Japan Development Service Co., Ltd. to carry out research for the Country Gender Profile for Zambia from October 2015 to March 2016. This report was prepared based on a desk review and field research in Zambia during this period as a reference for JICA for its implementation of development assistance for Zambia. The views and analysis contained in the publication, therefore, do not necessarily reflect the views of JICA. SUMMARY I. General Situation of Women and Government’s Efforts towards Gender Equality General Situation of Women in the Republic of Zambia In the Republic of Zambia (hereinafter referred to as “Zambia”, there exists a deep-rooted concept of an unequal gender relationship in which men are considered to be superior to women. This biased view regarding gender equality originates from not only traditional cultural and social norms but also from the dual structure of statutory law and customary law. Rights, which are supposed to be protected under statutory law, are not necessarily observed and women endure unfair treatment in terms of child marriage, unequal distribution of property, etc. Meanwhile, there have been some positive developments at the policy level, including the establishment of an independent Ministry of Gender, introduction of specific gender policies and revision of certain provisions of the Constitution, which epitomise gender inequality (currently being deliberated). According to a report1 published in 2015, Zambia ranks as low as 11th of 15 countries surveyed among Southern African Development Community (SADC) members in the areas of women’s participation in politics. -

Chap2 Baro 2015 Govfin2

Forgotten by families Anushka Virahsawmy CHAPTER 2 Gender and governance Articles 12-13 Namibia scored a goal for gender equality in its November 2014 elecions. KEY POINTS Photo courtesy of All Africa.com • The year 2015 marks the deadline for the SADC region to have reached gender parity in all areas of decision-making. No country has reached the 50% target of women's representation in parliament, cabinet or local government. • Over the past six years, women's overall representation in parliament has gone up by only two percentage points from 25% in 2009 to 27% in 2015. Seychelles (4th) and South Africa (7th) are the only two SADC countries in the top ten global ranking of women parliamen- tarians. However as a region SADC is five percentage points ahead of the global average of women in parliament (22%). • Women's representation in local government has increased by a mere one percentage point from 23% in 2009 to 24% in 2015. • Women's representation in cabinet has virtually remained stagnant at 22% since 2009. • Women in eight SADC countries have, for the first time, occupied top positions during the monitoring period. In June, Mauritius became the second SADC country after Malawi to have a woman President. SADC currently has a woman vice president in Zambia, as well as a woman prime minister and deputy prime minister in Namibia. • Between July 2015 and the end of 2016, seven more SADC countries - DRC (local); Lesotho (local), Madagascar (local), Tanzania (Tripartite) and Zambia (National), South Africa and Namibia (local) are due to hold elections. -

Joint Programme on Gender Based Violence

Country : Zambia GRZ - UN JOINT PROGRAMME ON GENDER - BASED VOILENCE Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ)-United Nations (UN) Joint Programme on Gender Based Violence Joint Programme Goal: Reduce Gender Based Violence (GBV) cases in Zambia Joint Programme Objective: To establish an integrated and multi-sectoral mechanism for the implementation of the Anti-Gender Based Violence Act Joint Programme Outcomes: Outcome 1: GBV survivors have increased access to timely and appropriate health services Outcome 2: GBV survivors have increased access to an efficient justice delivery system. Outcome 3: Survivors of GBV have increased access to protection and support services Outcome 4: GCDD has coordinated an affective, evidence based and multi-sectoral response to GBV in Zambia. National Execution Agency: Ministry of Finance and National Planning (MoFNP) Implementing Partner: Gender and Child Development Division (GCDD) Other Partners: Programme Duration: 4 years Total estimated budget*: USD15,800,000 Programme ID: Out of Which: Anticipated start/end dates: May 2012- May 2016 1. Funded Budget: Fund Management Option(s): Combination of Parallel 2. Unfunded Budget: and Pass through *Total estimated budget includes both programme costs and Managing or Administrative Agent: United Nations indirect support costs Development Programme (UNDP) Sources of funded budget ILO : IOM : UNDP : UNFPA : UNICEF : WHO : Government : Other : 1 Endorsed by the United Nations Country Team and National Counterparts: UN organizations UN organizations ILO IOM Name of Representative: Martin Chief of Mission: Andrew Choga Clemensson Signature Signature Date Date UNDP WHO Country Director: Viola Morgan Name of Representative: Olusegun Babaniyi Signature Signature Date Date UNFPA UNICEF Name of Representative: Duah Name of Representative: Iyorlumun Uhaa Owusu-Sarfo Signature Signature Date Date ______________________________________ Ms. -

Zambia CP Assessment and Mapping Report

MINISTRY OF GENDER AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT 2012 Child protection system mapping & assessment report (Zambia) Acknowledgements Foreword It gives me great pleasure as Minister of Gender and Child Development to present the report on the research that was conducted on the child protection system in Zambia. The purpose of the research was to establish the This report on the Child Protection System Mapping I am also grateful to various institutions and gaps, strengths and weaknesses in child protection and assessment has been made possible through organisations who have conducted extensive and come up with clear recommendations in the participation of various Government Ministries/ research on Child related issues in Zambia. The order to strengthen the various components of the Institutions, co-operating partners, civil society and findings in their reports provided much of the child protection system, including development of community members. essential background information during this clearly elaborated and user-friendly child protection research. framework which will facilitate the development of a First and foremost, I would like to express my National Child Protection Policy. The National Child sincere gratitude to UNICEF for providing financial Lastly, I would like to thank respondents Protection Policy once developed will form a basis for and technical support towards the process. drawn from the communities in the districts of all child protection initiatives and upon which the child Lusaka, Luangwa, Ndola, Mpongwe, Chipata, protection frame will be anchored. Furthermore, I would like to thank Children in Lundazi, Mongu, Senanga, Solwezi, Mwinilunga, Need Network (CHIN) for their input and support in Kabwe, Mumbwa, Mansa, Nchelenge, Kasama, It is expected that an improved child protection system spearheading the research and report writing. -

Gender Equality Plans in Latin America and the Caribbean Road Maps for Development Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean STUDIES 1

Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean STUDIES 1 Gender equality plans in Latin America and the Caribbean Road maps for development Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean STUDIES 1 Gender equality plans in Latin America and the Caribbean Road maps for development Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Antonio Prado Deputy Executive Secretary María Nieves Rico Chief, Division for Gender Affairs Ricardo Pérez Chief, Publications and Web Services Division This document was prepared under the supervision of Alicia Bárcena, Executive Secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). The work was coordinated by María Nieves Rico, Chief of the Division for Gender Affairs of ECLAC. The text was drafted by María Cristina Benavente and Alejandra Valdés Barrientos, Researchers with the Division for Gender Affairs. The authors wish to express particular thanks for the collaboration of Iliana Vaca-Trigo, Associate Social Affairs Officer in the Division for Gender Affairs; Marina Casas, Research Associate with the Division for Gender Affairs; and Pablo Tapia and Vivian Souza, Assistants with the Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. Thanks are also due to Karen Armas and Gabriela Sanzana. The preparation of this study has been made possible by the contributions of the member countries of the Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean, which regularly input qualitative and quantitative information to the Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean and to ECLAC, to analyse the progress of gender equality policies in the region. ECLAC also wishes to express gratitude for the financial and technical cooperation provided by the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID). -

Report of the Committee on Legal Affairs, Governance, Human Rights

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON LEGAL AFFAIRS, GOVERNANCE, HUMAN RIGHTS, GENDER MATTERS AND CHILD AFFAIRS ON THE REPORT OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF GENDER MAINSTREAMING ACTIVITIES IN ZAMBIA Consisting of: Mr J J Mwiimbu, MP (Chairperson); Mr S Chisanga, MP; Ms C Namugala, MP; Mr M A Malama, MP; Dr L M Kaingu, MP; Mr S Mushanga, MP; Mr J M Kapyanga, MP; and Mr K K Hamudulu, MP. The Honourable Mr Speaker National Assembly Parliament Buildings P O Box 31299 LUSAKA Sir, Your Committee has the honour to present its report on Auditor-General’s for the Report of the Gender Mainstreaming activities in Zambia. Functions of the Committee 2. In addition to any other duties conferred upon it by Mr Speaker or any Standing Order or any other order of the Assembly, the duties of the Committee on Legal Affairs, Governance, Human Rights, Gender Matters and Child Affairs are as follows: (a) to study, report and make appropriate recommendations to the Government through the House on the mandate, management and 1 operations of the Government ministries, departments and/or agencies under its portfolio; (b) to carry out detailed scrutiny of certain activities being undertaken by the Government ministries, departments and/or agencies under its portfolio and make appropriate recommendations to the House for ultimate consideration by the Government; (c) to make, if considered, necessary, recommendations to the Government on the need to review certain policies and certain existing legislation; and (d) to consider any Bills that may be referred to it by the House. Meetings of the Committee 3. -

Zambia GJLG Summit Report

MoGCW LGAZ REPORT ZAMBIA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND GENDER JUSTICE NATIONAL SUMMIT AND AWARDS Cresta Golf view Hotel, Lusaka, Zambia 7-8 March 2012 Official Opening of the Zambia GJLG Summit 2012 by Lusaka City Council Deputy Mayor – Albert Ngosa 1 Executive summary QUICK FACTS: . 51 Entries, 73 participants (28 females, 45 males) . 18 Entries from women, 33 Entries by men in 7 categories.(Prevention, Local economic Development, Leadership, Centres of Excellence ,HIV/AIDS ,Gender and Governance) . 5 women and 1 men are runners up . 3 women and 5 men are winners The First ever Zambia Gender Justice and Local Government Summit and Awards was held in Lusaka from the 7 – 8 March 2012 with awards given to 5 women and 5 men whose work on the ground won the highest accolades from judges and participants during presentations a detailed participants list is attached at Annex A outlining the contact details of all the delegates who attended the two day summit. The Summit was successfully held in partnership with Ministry of Gender and Child Development, Local Government Association of Zambia and was sponsored by GL and UNICEF Zambia. The summit featured 51 entries from 5 Provinces in a variety of categories including prevention, response, support, Local Economic Development, leadership, HIV/AIDS and Care Work, 16 Days campaigns (and Cyber dialogues), Institutional COE excellence awards. See Annex C for the featured entries. A full summit and awards programme outlining all of the key activities is attached at Annex B. Under the banner “365 days of local action to end violence and empower women” the summit and awards brought together journalists, local government authorities, municipalities, NGOs and representatives from ministries of gender and local government.