Songbook the Complete Mark Stone Stephen Barlow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Syphilis' Impact on Late Works of Classical Music Composers

SYPHILIS’ IMPACT ON LATE WORKS OF CLASSICAL MUSIC COMPOSERS Rempelakos L1, Poulakou-Rebelakou E1, Tsiamis C1, Rempelakos A2 1History of Medicine, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece 2Urologic Department, Hippocrateion Hospital, Athens, Greece INTRODUCTION & OBJECTIVE: To present the effects of the tertiary stage syphilis on the last works of some famous European classical music composers who suffered from the disease. METHODS: The review of the biographies of seven documented syphilis cases of composers, focusing on the events of their last period of life and the review of the critics for their artistic expression under disease-affected circumstances. RESULTS: The 19th century is undeniably considered as the golden age of classical music but, at the same time, some of the most famous composers were victims of this disease-menace, strongly stigmatizing themselves and their families, the latter trying to keep the shameful secret, aftermath destructing sources and documents. Seven cases of musicians with syphilis have been studied: Franz Schubert died at the age of 31, while Robert Schumann and Hugo Wolf (age at death 46 and 43 respectively), both attempted suicide and passed the rest of their lives in insane asylums. Moreover, Gaetano Donizetti infected his wife, Virginia, who died in childbirth before his own death occurring between catatonic symptoms and bouts of persecution mania. Bedrich Smetana predicted his death entitling his composition “final page” and indeed, he did not compose anymore and died soon in a mental asylum. Frederick Delius lived for fifteen years blind and paralyzed dictating his scores to a young follower of his music, although the quality of the late compositions cannot be compared with the priors. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Volume One of the Frederick Delius

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Volume One of the Frederick Delius Songbook to be Released in the United States this September ASHFORD, CONNECTICUT (August 22, 2011) – In honor of the 150th anniversary of the birth of the great English composer Frederick Delius (1862-1934), The Complete Delius Songbook – Volume 1 will be released as a CD in the U.S. on September 13, 2011. This is the first volume in a two-volume series that will comprise the first-ever complete recording of all 61 surviving songs of Frederick Delius for voice and piano. This recording features baritone Mark Stone accompanied by Stephen Barlow on piano. Michael Maglaras of 217 Records is Executive Producer. Produced and released first in the United Kingdom on July 18, 2011 on the Stone Records label, and produced in association with 217 Records, this eventual two-volume journey through the Delius songbook will be a delight to listeners everywhere. Pictured: Stephen Barlow and Mark Stone. “We at 217 Records cannot imagine a finer exponent of the English art song than baritone Mark Stone. That he possesses a superb instrument is clear to everyone who knows his work. But he is also a singer of rare intelligence and refinement, and this recording bears his unmistakable stamp,” said Michael Maglaras. “Stephen Barlow is the logical successor to Gerald Moore. He is a great English pianist who brings not only gracious support to this undertaking, but helps create, in every song, an immediate sense of both the drama and the deeper meaning of Delius’s work.” Volume 1, which includes first-time recordings of five of these songs, features all of Delius’s songs to English and Norwegian texts, the latter being sung in English translation. -

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No 298662) President Lionel Carley BA, PhD Vice Presidents Roger Buckley Sir Andrew Davis CBE Sir Mark Elder CBE Bo Holten RaD Piers Lane AO, Hon DMus Martin Lee-Browne CBE David Lloyd-Jones BA, FGSM, Hon DMus Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Anthony Payne Website: delius.org.uk ISSN-0306-0373 THE DELIUS SOCIETY Chairman Position vacant Treasurer Jim Beavis 70 Aylesford Avenue, Beckenham, Kent BR3 3SD Email: [email protected] Membership Secretary Paul Chennell 19 Moriatry Close, London N7 0EF Email: [email protected] Journal Editor Katharine Richman 15 Oldcorne Hollow, Yateley GU46 6FL Tel: 01252 861841 Email: [email protected] Front and back covers: Delius’s house at Grez-sur-Loing Paintings by Ishihara Takujiro The Editor has tried in good faith to contact the holders of the copyright in all material used in this Journal (other than holders of it for material which has been specifically provided by agreement with the Editor), and to obtain their permission to reproduce it. Any breaches of copyright are unintentional and regretted. CONTENTS EDITORIAL ..........................................................................................................5 COMMITTEE NOTES..........................................................................................6 SWEDISH CONNECTIONS ...............................................................................7 DELIUS’S NORWEGIAN AND DANISH SONGS: VEHICLES OF -

Now We Are 126! Highlights of Our 3 125Th Anniversary

Issue 5 School logo Sept 2006 Inside this issue: Recent Visits 2 Now We Are 126! Highlights of our 3 125th Anniversary Alumni profiles 4 School News 6 Recent News of 8 Former Students Messages from 9 Alumni Noticeboard 10 Fundraising 11 A lot can happen in 12 just one year In Memoriam 14 Forthcoming 16 Performances Kim Begley, Deborah Hawksley, Robert Hayward, Gweneth-Ann Jeffers, Ian Kennedy, Celeste Lazarenko, Louise Mott, Anne-Marie Owens, Rudolf Piernay, Sarah Redgwick, Tim Robinson, Victoria Simmons, Mark Stone, David Stout, Adrian Thompson and Julie Unwin (in alphabetical order) performing Serenade to Music by Ralph Vaughan Williams at the Guildhall on Founders’ Day, 27 September 2005 Since its founding in 1880, the Guildhall School has stood as a vibrant showcase for the City of London's commitment to education and the arts. To celebrate the School's 125th anniversary, an ambitious programme spanning 18 months of activity began in January 2005. British premières, international tours, special exhibits, key conferences, unique events and new publications have all played a part in the celebrations. The anniversary year has also seen a range of new and exciting partnerships, lectures and masterclasses, and several gala events have been hosted, featuring some of the Guildhall School's illustrious alumni. For details of the other highlights of the year, turn to page 3 Priority booking for members of the Guildhall Circle Members of the Guildhall Circle are able to book tickets, by post, prior to their going on sale to the public. Below are the priority booking dates for the Autumn productions (see back cover for further show information). -

Disability and Music

th nd 19 November to 22 December UKDHM 2018 will focus on Disability and Music. We want to explore the links between the experience of disablement in a world where the barriers faced by people with impairments can be overwhelming. Yet the creative impulse, urge for self expression and the need to connect to our fellow human beings often ‘trumps’ the oppression we as disabled people have faced, do face and will face in the future. Each culture and sub-culture creates identity and defines itself by its music. ‘Music is the language of the soul. To express ourselves we have to be vibrating, radiating human beings!’ Alasdair Fraser. Born in Salford in 1952, polio survivor Alan Holdsworth goes by the stage name ‘Johnny Crescendo’. His music addresses civil rights, disability pride and social injustices, making him a crucial voice of the movement and one of the best-loved performers on the disability arts circuit. In 1990 and 1992, Alan co- organised Block Telethon, a high-profile media and community campaign which culminated in the demise of the televised fundraiser. His albums included Easy Money, Pride and Not Dead Yet, all of which celebrate disabled identity and critique disabling barriers and attitudes. He is best known for his song Choices and Rights, which became the anthem for the disabled people’s movement in Britain in the late 1980s and includes the powerful lyrics: Choices and Right That’s what we gotta fight for Choices and rights in our lives I don’t want your benefit I want dignity from where I sit I want choices and rights in our lives I don’t want you to speak for me I got my own autonomy I want choices and rights in our lives https://youtu.be/yU8344cQy5g?t=14 The polio virus attacked the nerves. -

2017 Season 2

1 2017 SEASON 2 Eugene Onegin, 2016 Absolutely everything was perfection. You have a winning formula Audience member, 2016 1 2 SEMELE George Frideric Handel LE NOZZE DI FIGARO Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE Claude Debussy IL TURCO IN ITALIA Gioachino Rossini SILVER BIRCH Roxanna Panufnik Idomeneo, 2016 Garsington OPERA at WORMSLEY 3 2017 promises to be a groundbreaking season in the 28 year history of Cohen, making his Garsington debut, and directed by Annilese Miskimmon, Garsington Opera. Artistic Director of Norwegian National Opera, who we welcome back nine years after her Il re pastore at Garsington Manor. We will be expanding to four opera productions for the very first time and we will now have two resident orchestras as the Philharmonia Orchestra joins us for Our fourth production will be a revival from 2011 of Rossini’s popular comedy, Pelléas et Mélisande. Il turco in Italia. We are delighted to welcome back David Parry, who brings his conducting expertise to his 13th production for us, and director Martin Duncan Our own highly praised Garsington Opera Orchestra will not only perform Le who returns for his 6th season. nozze di Figaro, Il turco in Italia and Semele, but will also perform the world premiere of Roxanna Panufnik’s Silver Birch at the conclusion of the season. To cap the season off we are very proud to present a brand new work commissioned by Garsington from composer Roxanna Panufnik, to be directed Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy’s only opera and one of the seminal works by our Creative Director of Learning & Participation, Karen Gillingham, and I of the 20th century, will be conducted by Jac van Steen, who brought such will conduct. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

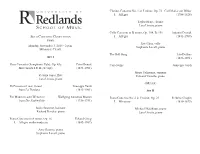

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

DELIUS BOOKLET:Bob.Qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1

DELIUS BOOKLET:bob.qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1 second piece, Summer Night on the River, is equally evocative, this time suggested by the river Loing that lay at the the story of a voodoo prince sold into slavery, based on an episode in the novel The Grandissimes by the American bottom of Delius’s garden near Fontainebleau, the kind of scene that might have been painted by some of the French writer George Washington Cable. The wedding dance La Calinda was originally a dance of some violence, leading to painters that were his contemporaries. hysteria and therefore banned. In the Florida Suite and again in Koanga it lacks anything of its original character. The opera Irmelin, written between 1890 and 1892, and the first attempt by Delius at the form, had no staged Koanga, a lyric drama in a prologue and three acts, was first heard in an incomplete concert performance at St performance until 1953, when Beecham arranged its production in Oxford. The libretto, by Delius himself, deals with James’s Hall in 1899. It was first staged at Elberfeld in 1904. With a libretto by Delius and Charles F. Keary, the plot The Best of two elements, Princess Irmelin and her suitors, none of whom please her, and the swine-herd who eventually wins is set on an eighteenth century Louisiana plantation, where the slave-girl Palmyra is the object of the attentions of her heart. The Prelude, designed as an entr’acte for the later opera Koanga, makes use of four themes from Irmelin.