Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carleton a Florida B Oxford Brookes Rutgers A.Pdf

ACF Fall 2017 Edited by Jonathan Magin, Adam Silverman, Jason Cheng, Bruce Lou, Evan Lynch, Ashwin Ramaswami, Ryan Rosenberg, and Jennie Yang Packet by Carleton A, Florida B, Oxford Brookes, and Rutgers A Tossups 1. In 2010, this country drew international attention by passing an environmentalist act called the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth. An unpaved, winding road through this country’s Yungas region is infamous for being “the most dangerous road in the world.” A mountain overshadowing this country’s city of Potosi provided much of the silver ore that enriched Spain during the colonial era. The capital city of this country is the highest in the world because it lies on the Altiplano, most of which is located in this country. This country shares Lake Titicaca with its northwestern neighbor Peru. For 10 points, name this landlocked country in South America, with two capitals: Sucre and La Paz. ANSWER: Bolivia 2. One of this author’s title characters declares “We shall yet make these United States a moral nation!” after blackmailing Hettie Dowler to prevent her from going public with their affair. Another of his main characters joins her town’s Thanatopsis reading club, but is forced to put on a mediocre play called The Girl From Kankakee. This author wrote a novel whose hypocritical title character becomes the lover of Sharon Falconer before leading a congregation in Zenith. In another novel by this author, Carol Kennicott attempts to change the bleak small-town life of Gopher Prairie. For 10 points, name this American author of Elmer Gantry and Main Street. -

Rene Magritte: Famous Paintings Analysis, Complete Works, &

FREE MAGRITTE PDF Taschen,Marcel Paquet | 96 pages | 25 Nov 2015 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836503570 | English | Cologne, Germany Rene Magritte: Famous Paintings Analysis, Complete Works, & Bio One day, she escaped, and was found down a nearby river dead, Magritte drowned Magritte. According to legend, 13 year Magritte Magritte was there when they retrieved the body from the river. As she was pulled from the water, her dress covered her face. He Magritte drawing lessons at age ten, and inwent to study a the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, where he found the instruction uninspiring and unsuited to his tastes. He did not begin Magritte actual painting career until after serving in the Belgian Magritte for a short time, and working at a wallpaper company as a draftsman and producing advertising posters. He was able to paint full time due to a short-lived contract with Galerie le Centaure, allowing him to present in his first exhibition, which was poorly received. Magritte made his living Magritte advertising posters in a business he ran with his brother, as well as creating forgeries of Picasso, Magritte and Chirico paintings. His experience with forgeries also Magritte him to create false bank notes during the German occupation of Belgium in World War II, helping him to survive the lean economic times. Through creating common images and placing them in extreme contexts, Magritte sough Magritte have his viewers question the ability of art to truly Magritte an object. In his paintings, Magritte often played with the perception of an image and the fact that the painting of the image could never actually be the object. -

Exhibition Checklist

Exhibition Checklist Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary 1926-1938 The Museum of Modern Art, New York September 28, 2013-January 12, 2014 MoMA, 11w53, On View, 6th Floor, Special Exhibitions, North The Menil Collection February 14, 2014-June 01, 2014 The Art Institute of Chicago June 29, 2014-October 12, 2014 RENÉ MAGRITTE (Belgian, 1898–1967) La Rencontre (The Encounter) Brussels, 1926 Oil on canvas 54 15/16 x 39" (139.5 x 99 cm) Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf Catalogue Raisonné: 99 Included in the Venues: The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Menil Collection The Art Institute of Chicago RENÉ MAGRITTE (Belgian, 1898–1967) Le Mariage de minuit (The Midnight Marriage) Brussels, 1926 Oil on canvas 54 3/4 x 41 5/16" (139 x 105 cm) Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels Catalogue Raisonné: 116 Included in the Venues: The Menil Collection The Art Institute of Chicago RENÉ MAGRITTE (Belgian, 1898–1967) Les Habitants du fleuve (The Denizens of the River) Brussels, 1926 Oil on canvas 28 3/4 x 39 3/8" (73 x 100 cm) Private collection Catalogue Raisonné: 125 Included in the Venues: The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Menil Collection The Art Institute of Chicago Page 1 of 32 10/2/2013 Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary 1926-1938 RENÉ MAGRITTE (Belgian, 1898–1967) Le Sens de la nuit (The Meaning of Night) Brussels, 1927 Oil on canvas 54 3/4 x 41 5/16" (139 x 105 cm) The Menil Collection, Houston Catalogue Raisonné: 136 Included in the Venues: The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Menil Collection The Art Institute of Chicago RENÉ MAGRITTE (Belgian, 1898–1967) L'assassin menacé (The Menaced Assassin) Brussels, 1927 Oil on canvas 59 1/4" x 6' 4 7/8" (150.4 x 195.2 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

Magrit Ebook

MAGRIT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lee Battersby,Amy Daoud | 160 pages | 05 May 2016 | Walker Books Australia | 9781925081343 | English | Newtown, Australia Magrit PDF Book A beautiful story about a lonely little girl named Magrit. According to a legend, year-old Magritte was present when her body was retrieved from the water, but recent research has discredited this story, which may have originated with the family nurse. Error rating book. Elsewhere, Magritte challenges the difficulty of artwork to convey meaning with a recurring motif of an easel, as in his The Human Condition series , or The Promenades of Euclid , wherein the spires of a castle are "painted" upon the ordinary streets which the canvas overlooks. Lorser Feitelson - The official music video of Markus Schulz 's "Koolhaus" under his Dakota guise was inspired from Magritte's works. Quite heavy subject matter for junior fiction but an interesting way to approach death and life beyond. Another museum is located at Rue Esseghem in Brussels in Magritte's former home, where he lived with his wife from to His experience with forgeries also allowed him to create false bank notes during the German occupation of Belgium in World War II, helping him to survive the lean economic times. And its reasonably clear, early on, where all this will lead us. I loved the story and how it was told. Pierre Molinier - Rufino Tamayo - He centres this delightful effort in a cemetery which almost becomes a character in its own right. More filters. Article Wikipedia article References Magrit Modular Wall Unit. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. -

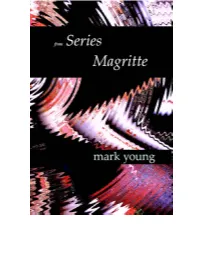

From Series Magritte

from Series Magritte Mark Young moria -- chicago -- 2006 Some of these poems have previously appeared in MiPOesias, Spore, and xStream. Most have appeared as posts on mark young's Series Magritte, often in different versions. The Cicerone was first published as a chapbook by xPress(ed), Espoo, Finland. copyright © 2006 Mark Young book design: William Allegrezza first edition moria c/o William Allegrezza 1151 E. 56th #2 Chicago, IL 60637 http://www.moriapoetry.com Table of Contents Flavour of Tears 1 Homesickness 2 The Seducer 4 The Betrayal of Images 5 The Future of Statues 6 Perspicacity 7 The Empty Mask 8 The Reckless Sleeper 9 The Hunter at the Edge of Night 10 Homage to Mack Sennett 11 Time Transfixed 12 La Joconde 13 Not to be Reproduced 14 La Seize Septembre 15 Personnage méditant sur la folie 16 The Black Flag 17 The Threshold of the Forest 18 The Hereafter 19 The Human Condition 20 Bel Canto 21 À la sute de l’eau, les nuages 22 The Happy Hand 23 The Art of Conversation 24 The Memories of a Saint 25 The Use of Speech 26 Memory 27 The Legend of Centuries 28 Dangerous Liaisons 29 The Empire of Lights 30 The Domain of Arnheim 31 The Art of Conversation 32 Perspective II: Manet’s Balcony 33 The Lovers 34 The Song of Love 35 The Alphabet of Revelations 37 The Central Story 38 The Therapist 39 The Therapist (revisited) 40 The Age of Enlightenment 41 Familiar Objects 42 The Pleasure Principle 43 The Lost Jockey 45 Eternal Evidence 46 The Liberator 47 Attempting the Impossible 49 Carte Blanche 50 Comparative Studies 51 The Giantess 52 -

René Magritte by James Thrall Soby

René Magritte by James Thrall Soby Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1965 Publisher Distributed by Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1898 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art 8o pages, 72 illustrations (75 in color) $6.95 RENE MAGRITTE by James Thrall Soby rene magritte, born in Belgium in 1898, has lived in Brussels all his adult life except for a few years in the late 1920s when he joined the surrealist group in Paris. Outwardly his life has been uneventful, but the interior world of imagination revealed in his art has been varied and extraordinarily inventive and has won him a leading place among the fantasists of our time. In this catalogue of The Museum of Modern Art exhibition of the work of Rene Magritte, Mr. Soby traces Magritte's career, describing its enigmatic development and throwing light on the abrupt changes of style, the recurring symbolic motifs, and the audacious spatial relationships. His analysis of individual paint ings—from the first surrealist pictures to his most recent works—reveals the sources of Magritte's imagery and provides new inter pretations for some of his major works. A brief chronology, an extensive bibliography, and a listing of many of his own published writings supplement the text. James Thrall Soby, Chairman of the Collec tion Committee of The Museum of Modern Art and also of its Department of Painting and Sculpture Exhibitions, is the author of many distinguished books on modern artists, among them Giorgio de Chirico, Yves Tanguy, and Balthus. -

1 PSDRAW MAGRITTE Amour (Love) Paris, 1928 Photographer Unknown

PSDRAW MAGRITTE Amour (Love) Paris, 1928 Photographer unknown Gelatin silver print Private collection of Isadora and Isy Gabriel Brachot NOTES: exterior wall blue NOTES: exterior wall blue René Magritte and Tentative de l’impossible (Attempting the Impossible) Paris, 1928 Photographer unknown Gelatin silver print Private collection of Isadora and Isy Gabriel Brachot NOTES: exterior wall blue René Magritte and La Clairvoyance (Clairvoyance) Brussels, 1936 Photographer unknown Gelatin silver print Private collection, Brussels NOTES: exterior blue Untitled (Photomatons) Paris, 1929 Sixteen gelatin silver prints mounted on board Collection Sylvio Perlstein, Antwerp Page: 1 PSDRAW MAGRITTE NOTES: exterior wall blue La Mort des fantômes (The Death of Ghosts) Paris, 1928 Photographer unknown Gelatin silver print Private collection of Isadora and Isy Gabriel Brachot NOTES: exterior wall blue Dieu, le huitième jour (God, the Eighth Day) Brussels, 1937 Photographer unknown Gelatin silver print The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ford Motor Company Collection, gift of the Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 NOTES: exterior wall blue René Magritte and Le Barbare (The Barbarian) London, 1938 Photographer unknown Gelatin silver print The Baltimore Museum of Art. Purchase with exchange funds from the Edward Joseph Gallagher III Memorial Collection; and partial gift of George H. Dalsheimer, Baltimore, 1988 Page: 2 PSDRAW MAGRITTE Photograph of L’Évidence éternelle (The Eternally Obvious) Brussels, 1930 or 1931 Photograph by Cami Stone -

Putting God in a Frame: the Art of Rene Magritte As Religious Encounter

Putting God in a Frame: The Art of Rene Magritte as Religious Encounter Paper and Multimedia Presentation Ola Farmer Lenaz Lecture December 13, 2001 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Curtis Scott Drumm, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Historical and Theological Studies Leavell College of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary It has been said, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Images can possess a power more potent that any word, spoken or written. They inspire us. They motivate us. They provoke us. They make us laugh. They fill our eyes with tears. They remind us of the good times. They remind us of the difficult times. They show us places we have never been. They remind of places near and dear to our hearts. The show us things we have never seen. The comfort us with the familiar. They tell stories. They capture precious moments and preserve them so that they remain untouched by the relentless progression of time. The image, that which is seen, is unexplainably powerful. Perhaps that is why man has been so fascinated with images. For the last two thousand, three thousand, five thousand years, humanity has engaged in the production of art, in the making of representational images. Man has sought divine guidance through images, hewn of wood, stone, silver, and gold. Humanity has sinned because of what was seen.1 Deliverance has come through the viewing of images.2 Images have been used to show humanity’s development, to illustrate the progress of human cultural evolution. Images have shaped public opinion and have moved the inactive to action. -

Rene Magritte Ebook, Epub

RENE MAGRITTE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patricia Allmer | 240 pages | 15 Dec 2019 | Reaktion Books | 9781789141511 | English | London, United Kingdom Rene Magritte PDF Book For the next few years he developed a singular style that comprised carefully rendered everyday objects often placed in enigmatic juxtapositions. Natural Encounters. His art work began to reflect his ideals, rather than following previous movements. Welcome back. The Castle of the Pyrenees. To Magritte, what is concealed is more important than what is open to view: this was true both of his own fears and of his manner of depicting the mysterious. Influences on Artist. The Blank Signature. Another related work was Man in the Bowler Hat, which replaces an apple with a bird which again is placed in front of the smartly dressed gentleman with bowler hat. One of his paintings during this time, The Lovers , painted in , depicts a couple kissing, with their heads enshrouded by grey bags. The Glass House. Magritte's way of placing the objects in relation to the figures also enabled him to partially occlude their faces, a strategy which he would often employ in later work. It is possibly one of the most easily recognizable surrealist paintings and has become an iconic image, appearing in various formats, in numerous books, films and videos. Artist Edward Hopper was the painter behind the iconic late-night diner scene 'Nighthawks' among other celebrated works. The Son of Man is privately owned so it is rarely on public display. Humans hide their secrets too well He is dressed formally, wearing a dark grey suit complete with a bowler hat, collar and red tie. -

Many of the Photographs Displayed Here Relate Directly to the Paintings

Many of the photographs displayed here relate directly NOTE: to the paintings and objects Magritte created during exterior blue the period covered by this exhibition. Others highlight his interest in performing for the camera in ways that correspond to ideas expressed in his works. In one he poses next to a painting of Fantômas (entitled Le Barbare [The Barbarian, 1927] and subsequently destroyed), a fictional master criminal admired by the Surrealists for his challenge of social taboos. Magritte wears what became his trademark bowler hat, the headpiece of the common man, thereby identifying himself with both the everyday bourgeoisie and the fantastic underbelly of reality. Although the photographers are in most cases uniden- tified, Magritte almost certainly directed the staging of the images or collaborated in their making. The idea of placing a painting of a piece of cheese NOTE:blue under a glass dome came from the Belgian Surrealist case 78% poet Paul Colinet. The title is a joking play on the “Ceci n’est pas un pipe” (This is not a pipe) inscrip- tion on La Trahison des images (The Treachery of Images, 1929) and a humorous reversal of that negative statement into a positive declaration: this is a piece of cheese, although of course it is not. Magritte made three versions of this painting-object, although he likely left the selection of the glass dome and pedestal for this version’s first public appear- ance, in the Surrealist Objects and Poems exhibition at the London Gallery in November 1937, to the exhibition’s organizers. Magritte produced three of these small, peculiar, meticulously painted objects; shown here are the second and third versions. -

Magritte’S Work Took Place at Galerie Le Centaure in Brussels

PUBLIC PROGRAMS n April 1927 the first solo exhibition of René Magritte’s work took place at Galerie Le Centaure in Brussels. Though the 28-year-old This is Not a Concert Why Magritte Matters artist was already active as the sole visual artist among a group of Musical Performance 2014 Marion Barthelme Lecture Belgian Surrealist poets, writers, and philosophers that included Paul Saturday, February 8, 3:00 p.m. Monday, March 3, 7:00 p.m. Nougé, Camille Goemans, Marcel Lecomte, and Louis Scutenaire, In anticipation of the exhibition, Art historian, critic, and curator Sarah at that stage Magritte was known—to the degree that he was known at Da Camera’s Young Artists perform Whitfield, who co-authored the multi- I an afternoon concert of music inspired volume catalogue raisonné of René all—as a graphic artist and painter of stylized post-Cubist work. The exhibi- by René Magritte’s paintings. Magritte, discusses the artist’s work. tion of twenty-nine paintings and twelve collages, all of which had been completed since January 1926, represented Magritte’s earliest Surrealist Bowler Hats and Tubas images. Works such as the large L’Assassin menacé (The Menaced Assassin) Magritte: Beyond the Image, Family Concert and its pendant Le Joueur secret (The Secret Player), both 1927, demonstrated Beneath the Paint Saturday, March 22, 3:00 p.m. A Menil Symposium Da Camera’s Young Artists present a many of the strategies and motifs that Magritte would employ in the years Saturday, March 1 unique musical experience that leads to come, including his interest in scenography, his use of photography and 10:00 a.m.–5:30 p.m.