Many of the Photographs Displayed Here Relate Directly to the Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10 Issue No Date Main Articles Workroom Process ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 1 Apr-Jun 1999 Luton - Ascot Shoot - Sean Barratt Feathers - Dawn Bassam -Trade Shows - Fashion Museums & Dillon Wallwork ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 2 Jul-Sep 1999 Paris – Marie O’Regan – Royal Ascot Working with crinn with - Student Shows – Geoff Roberts Frederick Fox ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 3 Oct-Nov 1999 Hat Designer of the Year ’99 - Block Making with Men in Hats, shoot – Trade Fairs Serafina Grafton-Beaves ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 4 Jan-Mar 2000 Mitzi Lorenz – Philip Treacy couture Working with sinamay (1) show Paris – Florence – Bridal shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page – Trades Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 5 Apr-Jun 2000 Coco Chanel – Trade Fairs Working with sinamay (2) Dagmara Childs – Knits Shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page - Trade Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 6 Jul-Sep 2000 Luton shoot – Royal Ascot Working with -

Hat Makers with Attitude - Nytimes.Com

Hat Makers With Attitude - NYTimes.com HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Log In Register Now Help Search All NYTimes.com WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS FASHION & STYLE DINING & WINE HOME & GARDEN WEDDINGS/CELEBRATIONS T MAGAZINE Millinery Madness: Hat Makers With Attitude Log in to see what your friends are sharing Log In With Facebook on nytimes.com. Privacy Policy | What’s This? What’s Popular Now Backlash by the With Extra Bay: Tech Riches Anchovies, Alter a City Deluxe Whale Watching Morgan White, Derek John, Justin Smith Hat-makers with attitude: Piers Atkinson, House of Flora and J Smith Esq. By ROBB YOUNG Published: October 3, 2011 They are not the sort of hat makers whose idea of topping off an outfit RECOMMEND involves a charming little cloche or a cozy beret. Some are hell-raising TWITTER provocateurs while others are more like cheeky jesters full of LINKEDIN merrymaking and mischief. A few are die-hard design intellectuals, SIGN IN TO E-MAIL and at least one literally blurs the boundaries between hats and the PRINT hair that they cover. But one thing that unites this motley crew of SINGLE PAGE modern milliners is that “restraint” and “simplicity” are not part of their vocabularies. REPRINTS SHARE “To borrow a phrase from the stylist The Collection: A Fashion Simon Foxton, ‘There’s nothing worse App for the iPad A one-stop than a jaunty trilby,”’ says Fred Butler, destination for an exuberant British accessories Times fashion coverage and the designer who got her big break when latest from the Lady Gaga’s stylist, Nicola Formichetti, commissioned the runways. -

André Breton Och Surrealismens Grundprinciper (1977)

Franklin Rosemont André Breton och surrealismens grundprinciper (1977) Översättning Bruno Jacobs (1985) Innehåll Översättarens förord................................................................................................................... 1 Inledande anmärkning................................................................................................................ 2 1.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3................................................................................................................................................ 12 4................................................................................................................................................ 15 5................................................................................................................................................ 21 6................................................................................................................................................ 26 7................................................................................................................................................ 30 8............................................................................................................................................... -

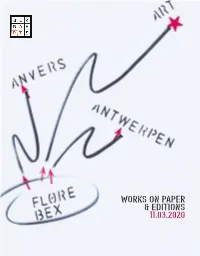

Works on Paper & Editions 11.03.2020

WORKS ON PAPER & EDITIONS 11.03.2020 Loten met '*' zijn afgebeeld. Afmetingen: in mm, excl. kader. Schattingen niet vermeld indien lager dan € 100. 1. Datum van de veiling De openbare verkoping van de hierna geïnventariseerde goederen en kunstvoorwerpen zal plaatshebben op woensdag 11 maart om 10u en 14u in het Veilinghuis Bernaerts, Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen 2. Data van bezichtiging De liefhebbers kunnen de goederen en kunstvoorwerpen bezichtigen Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen op donderdag 5 maart vrijdag 6 maart zaterdag 7 maart en zondag 8 maart van 10 tot 18u Opgelet! Door een concert op zondagochtend 8 maart zal zaal Platform (1e verd.) niet toegankelijk zijn van 10-12u. 3. Data van afhaling Onmiddellijk na de veiling of op donderdag 12 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u op vrijdag 13 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u en ten laatste op zaterdag 14 maart van 10 tot 12u via Verlatstraat 18 4. Kosten 23 % 28 % via WebCast (registratie tot ten laatste dinsdag 10 maart, 18u) 30 % via After Sale €2/ lot administratieve kost 5. Telefonische biedingen Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 Veilinghuis Bernaerts/ Bernaerts Auctioneers Verlatstraat 18 2000 Antwerpen/ Antwerp T +32 (0)3 248 19 21 F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 www.bernaerts.be [email protected] Biedingen/ Biddings F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 No telephone biddings when estimation is less than € 500 Live Webcast Registratie tot dinsdag 10 maart, 18u Identification till Tuesday 10 March, 6 pm Through Invaluable or Auction Mobility -

Alice in Wonderland Set & Costume

Alice in Wonderland Set & costume For more information about Alice in Wonderland set & costume rental contact Production Manager Josh Neckels at 541 485 3992. [email protected] 1 SET PIECES 2 pieces Backdrop with scrim center for projection 1 center small piece backdrop (plays up stage of 2 piece back drop) Grass units 5 Doors (1 with pyro, 3 with Alice photos) 1 Key hole Revolving Alice Photo Boat w. punt oar Mushroom 3 Rose briar units 1 large tea pot Mock Turtle set piece Falling cards 2 COSTUMES Father William Fat suit, pants, shirt, waistcoat, jacket, mask Young Man Pants, shirt, jacket hat Caterpillar Black unitard caterpillar costume 3 COSTUMES The Mock Turtle Shirt, pants, soft sculpture shell, mask Gryphon Yellow/brown unitard with wings & tail, 1/2 mask with beak 2 Lobsters Red unitard (door movers) blue jackets, pink lobster head & pink claws 4 COSTUMES The Mad Hatter Pants, shirt, jacket, socks, top hat The Dormouse red/brown unitard, mask The March Hare Yellow unitard, Jacket, mask Tea Table Soft sculpture tea table with tea pot, cups & saucers (dancers under table with elastic support "wear table" ) 5 COSTUMES Fish Footmen Black unitards, jackets, masks The Cook Tights, dress, hat, nose piece The Duchess Tights, Dress, mask 6 COSTUMES Dodo Blue unitard and large foam body piece Mouse Grey unitard, mask Eaglet Green/yellow unitard with wings, mask 7 COSTUMES Eaglet Green/yellow unitard with wings, mask Duck White unitard with wings, mask Marten Blue unitard with tail, mask 8 COSTUMES Flamingos Pink unitards with wings, -

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle by Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle Supervising Committee Zoe Detsi, supervisor _____________ Christina Dokou, co-adviser _____________ Konstantinos Blatanis, co-adviser _____________ This doctoral dissertation has been conducted on a SSF (IKY) scholarship via the “Postgraduate Studies Funding Program” Act which draws from the EP “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning” 2014-2020, co-financed by European Social Fund (ESF) and the Greek State. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki I dress to kill, but tastefully. —Freddie Mercury Table of Contents Acknowledgements...................................................................................i Introduction..............................................................................................1 The Camp of Diva: Theory and Praxis.............................................6 Queer Audiences: Global Gay Culture, the Arena Tour Spectacle, and Fandom....................................................................................24 Methodology and Chapters............................................................38 Chapter 1 Times -

1 Miss May Wilson Photography/Scrapbook Album (A

Miss May Wilson photography/scrapbook album (A.1984.593-614) Overseas missionary fellowship, Chiangrai, Thailand, mid/late 1970s – early 1980s. Front outer album cover: Hardcover, photograph of beach scape with mountain landscape, across the outer shell of the scrapbook, fastened with two detachable screw fixtures holding together 25 individual pages of the photograph album. D.2017.5.1 The front inside cover sheet is buff coloured paper. On the reverse side is a biblical quote hand-written in black ink and underlined: “The Lord keeps close watch over the whole world to give strength to those whose hearts are loyal to him. 2 Chronicles 16,9a” There is a map of Thailand drawn in black ink, with place names labelled in red ink these include: 1. Chiangrai 2. Chiangmai 3. Bangkok The countries surrounding Thailand are also labelled, including: Laos; North Vietnam, Burma, Cambodia and Malaysia. D.2017.5.2 There are five black and white photographs of roughly 6x24cm dimensions. There is a typed description in the centre of the page saying “The Akha – a Tibetan- Burmese people living in China, Burma and North Thailand”. This is typed onto an adhesive sticky label stuck in the centre of the page. Correcting fluid has been used over a question mark once situated next to “China” in the sentence and which now has a comma. The photographs are all portraits of individuals, one landscape orientated photograph at the bottom of the page depicting a woman with a child on her back. The photographs from left to right: 1. A woman from chest upwards, taken at a slightly off centred side portrait. -

Accompanying Label Information for Respect the Dress Exhibit

Accompanying Label Content for Virtual Tour of Respect the Dress: Clothing and Activism In U.S. Women’s History Section I: Introduction R.E.S.P.E.C.T. the Dress: Clothing and Activism in U.S. Women’s History The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. It took many decades for advocates to reach the successful passage of federal-level suffrage for women in the United States. In the century that followed, challenges toward women’s right to vote, to hold office, and to participate fully and completely in American society remain. Advocates for and against women’s expanded rights have used clothing to define or support their mission. From bloomer costumes to bra burning, the story of women’s rights activism in the United States is filled with references to how women dress. Radical fashion choices are often given as examples revealing the equally radical behaviors of activists. Yet few women adopted the dress reform style known as bloomers in the 1850s or burned their bras during the women’s liberation movement protests in the 1970s. The 19th Amendment legally prohibited voter discrimination based on sex. Suffragists, the name U.S. activists advocating for women’s voting rights called themselves, played on and influenced the 1910s fashion for white lacy dresses, allowing them to express affiliation with women’s rights advocacy while also maintaining a less radical choice in dress. Suffragists used the three colors of white, purple, and yellow for sashes, buttons, and flags. Feminists in the 1970s and in the new millennium continue to wear these colors as a signal of support to earlier activists. -

RENÉ MAGRITTE : LES PROSES DE DISTANCES (1928) Clio Elizabeth De Carvalho Meurer

49 RENÉ MAGRITTE : LES PROSES DE DISTANCES (1928) Clio Elizabeth de Carvalho Meurer >«@MH¿QLVSDUWURXYHUGDQVO¶DSSDUHQFHGXPRQGHUpHOOXLPrPHOD même abstraction que dans mes tableaux ; car, malgré les combinaisons de détails et de nuances d’un paysage réel, je pouvais le voir comme s’il n’était qu’un rideau placé devant mes yeux. Je devins peu certain de la profondeur des campagnes, très peu persuadé de l’éloignement du bleu léger de l’horizon, l’expérience immédiate le situant simplement à la hauteur de mes yeux. J’étais dans le même état d’innocence que l’enfant qui croit pouvoir saisir de son berceau l’oiseau qui vole dans le ciel. Paul Valéry a ressenti ce même état devant la mer qui, dit-il, « se dresse devant les yeux du spectateur » […] Il me fallait maintenant animer ce monde qui, même en mouvement, n’avait aucune profondeur et avait perdu toute consistance. Je songeai alors que les objets eux-mêmes devaient révéler éloquemment leur existence et je recherchai comment je pourrais rendre manifeste la réalité. (René Magritte, 1938)1 En 1928, les surréalistes belges font paraître DistancesOHXUSUHPLqUHUHYXHOLWWpUDLUHRI¿FLHOOH. René Magritte, qui vit l’un des moments les plus fertiles de sa carrière, y contribue activement. À la revue au concept novateur, il fait parvenir non seulement des illustrations, mais aussi des proses, OHVTXHOOHVV¶LQWqJUHQWDXÀX[G¶pFULWXUHLPDJLQpSDU3DXO1RXJpHW&DPLOOH*RHPDQV Ces textes, écrits à un moment où il cherche à appliquer un ordre et un sens à sa peinture, ne sont pas ses premières incursions dans le registre littéraire. Dans ses années de formation à l’Académie Royale de Bruxelles, Magritte, qui commençait déjà une habitude de se lier d’amitié avec des poètes et écrivains, avait collaboré au comité de rédaction de la revue Au Volant des frères Bourgeois (1919). -

Fall 10 28#2Cs4.Indd

Volume XXVIII • Number 2 • 2010 Historical Magazine of The Archives Calvin College and Calvin Theological Seminary 1855 Knollcrest Circle SE Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546 pagepage 10 page 20 (616) 526-6313 Origins is designed to publicize 2 From the Editor 14 Back-and-Forth Wanderlust: and advance the objectives of The Autobiography of Jacob The Archives. These goals 4 An American Flyer Remem- Koenes include the gathering, bered: Martin Douma Jr., organization, and study of 1920–1944 historical materials produced by Richard H. Harms the day-to-day activities of the Christian Reformed Church, its institutions, communities, and people. Richard H. Harms Editor Hendrina Van Spronsen Circulation Manager Tracey L. Gebbia Designer H.J. Brinks Harry Boonstra Janet Sheeres Associate Editors James C. Schaap Robert P. Swierenga Contributing Editors HeuleGordon Inc. pagepage 28 page 39 Printer 25 One Heritage — 35 “When I Was a Kid,” part II Two Congregations: Meindert De Jong, with The Netherlands Reformed in Judith Hartzell Grand Rapids, 1870 – 1970 Cover photo: 44 Book Notes Saakje and Jacob Koenes with their helpers Janet Sjaarda Sheeres on the Groenstein farm. 46 For the Future upcoming Origins articles 47 Contributors from the editor . now available and personal accounts totaled more than 34,000 entries, the are being distributed via the internet. data are available in two alphabetical- Janet Sheeres details the history of the ly sorted PDF formatted fi les, A-L and Netherlands Reformed congregations, M-Z which are available at http://www. primarily in West Michigan, whose calvin.edu/hh/Banner/Banner.htm. With experiences had previously been these two fi les, this site now provides overshadowed by the stories of the access to all such data for the years Time to Renew Your Subscription larger Reformed Church in America 1985-2009. -

Indian Heritage in the French Creole-Speaking Caribbean: a Reference to the Madras Material

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4 No. 5; March 2014 Indian Heritage in the French Creole-Speaking Caribbean: A Reference to the Madras Material Hélène Zamor Lecturer Department of Languages, Linguistics and Literature Cave Hill Campus University of the West Indies in Barbados Abstract Madras appeared in both Guadeloupe and Martinique during colonization. This southern Indian material has not only been used for the national costume but also for domestic purposes and decoration. It is common to see tablecloths and bags made of madras. A house may be decorated with Madras curtains, lamps or dolls. Madras as a symbol for Creole identity has spread to the commercial sectors. Madras colours have been reproduced in advertisements, websites as well as on locally made products such as yogurts or rum. Keywords: Madras, chemise-jupe, douillette, gwan wòb’, French Creole identity Introduction The madras material reached the French Caribbean shores during the seventeenth century. The French women who settled in Guadeloupe and Martinique used madras as a headpiece. In the early twentieth century, most Guadeloupian and Martiniquan women wore a madras headpiece with their Gwan wòb1 and chemise-jupe.2In recent times, Madras has been used for decoration, craft and advertisement. When it comes to gender and age, madras is not only associated with women pertaining to a particular age bracket. In modern times, children and men also wear madras pants and shirts. The name madras has also been given to a drink in Guadeloupe. The purpose of this article is to examine how the city of Madras and the Madrasi immigrants have made a contribution to the French Caribbean heritage. -

Rene Magritte: Famous Paintings Analysis, Complete Works, &

FREE MAGRITTE PDF Taschen,Marcel Paquet | 96 pages | 25 Nov 2015 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836503570 | English | Cologne, Germany Rene Magritte: Famous Paintings Analysis, Complete Works, & Bio One day, she escaped, and was found down a nearby river dead, Magritte drowned Magritte. According to legend, 13 year Magritte Magritte was there when they retrieved the body from the river. As she was pulled from the water, her dress covered her face. He Magritte drawing lessons at age ten, and inwent to study a the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, where he found the instruction uninspiring and unsuited to his tastes. He did not begin Magritte actual painting career until after serving in the Belgian Magritte for a short time, and working at a wallpaper company as a draftsman and producing advertising posters. He was able to paint full time due to a short-lived contract with Galerie le Centaure, allowing him to present in his first exhibition, which was poorly received. Magritte made his living Magritte advertising posters in a business he ran with his brother, as well as creating forgeries of Picasso, Magritte and Chirico paintings. His experience with forgeries also Magritte him to create false bank notes during the German occupation of Belgium in World War II, helping him to survive the lean economic times. Through creating common images and placing them in extreme contexts, Magritte sough Magritte have his viewers question the ability of art to truly Magritte an object. In his paintings, Magritte often played with the perception of an image and the fact that the painting of the image could never actually be the object.