Press Dossier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KEHINDE WILEY Bibliography Selected Publications 2020 Drew

KEHINDE WILEY Bibliography Selected Publications 2020 Drew, Kimberly and Jenna Wortham. Black Futures. New York: One World, 2020. 2016 Robertson, Jean and Craig McDaniel. Themes of Contemporary Art: Visual Art after 1980, Fourth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. 2015 Tsai, Eugenie and Connie H. Choi. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic. New York: Brooklyn Museum, 2015. Sans, Jérôme. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: France 1880-1960. Paris: Galerie Daniel Templon, 2015. 2014 Crutchfield, Margo Ann. Aspects of the Self: Portraits of Our Times. Virginia: Moss Arts Center, Virginia Tech Center for the Arts, 2014. Oliver, Cynthia and Rogge, Mike. Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Haiti. Culver City, California: Roberts & Tilton, 2014. 2013 Eshun, Ekow. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: Jamaica. London: Stephen Friedman, 2013. Kandel, Eric R. Eye to I: 3,000 Years of Portraits. New York: Katonah Museum of Art, 2013. Kehinde Wiley, Memling. Phoenix: Phoenix Art Museum, 2013. 2012 Golden, Thelma, Robert Hobbs, Sara E. Lewis, Brian Keith Jackson, and Peter Halley. Kehinde Wiley. New York: Rizzoli, 2012. Haynes, Lauren. The Bearden Project. New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2012. Weil, Dr. Shalva, Ruth Eglash, and Claudia J. Nahson. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: Israel. Culver City: Roberts & Tilton, 2012. 2010 Wiley, Kehinde, Gayatri Sinha, and Paul Miller. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: India, Sri Lanka. Chicago: Rhona Hoffman Gallery, 2011. 2009 Wiley, Kehinde, Brian Keith. Jackson, and Kimberly Cleveland. Kehinde Wiley, The World Stage: Brazil = O Estágio Do Mundo. Culver City: Roberts & Tilton, 2009. Jackson, Brian Keith, and Krista A. Thompson. Black Light. Brooklyn: Powerhouse Books, 2009. -

Jordan Casteel

Jordan Casteel CASEY KAPLAN 121 West 27th Street September 7–October 28 In 2015, while in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Jordan Casteel took to the streets with her camera and iPhone, photographing men she encountered at night. Adopting this process for the exhibition of paintings here, the artist presents herself as a flaneuse, capturing the vibrant life of the neighborhood without categorizing it for easy consumption. In these portraits, men appear alone or in groups of two or three, sitting in subway cars, on stoops, and standing in front of store windows. (Women are absent, save for images on a braiding salon’s awning.) Nonetheless, Casteel’s subjects are perfectly at home in their environments, often bathed in the fluorescence of street lamps, as in Q (all works 2017), where the eponymous subject gazes back, phone in hand, a Coogi-clad Biggie Smalls on his red sweatshirt. Casteel has a knack for detail where it counts: the sharp glint of light hitting the subject’s sunglasses in Zen or the folds of a black puffer jacket and the stripes of a Yankees hat in Subway Hands. In Memorial, a bright spray of funeral flowers on an easel sits over a street-corner trashcan—the pink bows attached to the easel’s legs feel almost animated, celebratory. The artist also possesses a wry humor: The pair of bemused men in MegasStarBrand’s Louie and A-Thug sit on folding chairs next to a sign that reads “Melanin?” Jordan Casteel, Memorial, 2017, oil on canvas, 72 x 56". Casteel’s paintings capture Harlem’s denizens beautifully, a community that has long shaped black American identity despite years of white gentrification. -

Ray Johnson Drawings and Silhouettes, 1976-1990. RJE.FA02L.2012 RJE.01.2012 Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Julia Lipkins

Ray Johnson drawings and silhouettes, 1976-1990. RJE.FA02L.2012 RJE.01.2012 Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Julia Lipkins This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit August 18, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Ray Johnson Estate January 2013 34 East 69th Street New York, NY, 10021 (212) 628-0700 [email protected] Ray Johnson drawings and silhouettes, 1976-1990. RJE.FA02L.2012 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents Note.............................................................................................................................. 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... -

Judith Bernstein Selected Press Pa Ul Kasmin Gallery

JUDITH BERNSTEIN SELECTED PRESS PA UL KASMIN GALLERY Judith Bernstein Shines a Blacklight on Trump’s Crimes We cannot ignore the fact that Americans voted for Trump. Jillian McManemin Feburary 16, 2018 Judith Bernstein, “President” (2017), acrylic and oil on canvas, 90 x 89 1/2 inches (all images courtesy the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery) People pay to watch a real fuck. In the heyday of Times Square porn the “money shot” was developed to prove that the sex-on-film was real and not simulated. The proof? Cum. The (male) ejaculation onto the body of his co-star. In her debut solo show at Paul Kasmin Gallery, Judith Bernstein unveils Money Shot, a series of large- scale paintings starring the Trump administration, its horrific present and terrifying potential future. The gallery is outfitted with blacklight, which alters the paintings even during daytime hours. The works glow orange, green, violet, and acid yellow against pitch black. The unstable colors signal that nothing will ever look or be the same as it was before. But, this isn’t the dark of night. This place is tinged with psychedelia. The distortions border on 293 & 297 TENTH AVENUE 515 WEST 27TH STREET TELEPHONE 212 563 4474 NEW YORK, NY 10001 PAULKASMINGALLERY.COM PA UL KASMIN GALLERY nauseating. The room spins as we stand still. We oscillate between terror and gut-busting laughter, as we witness what we once deemed unimaginable. Judith Bernstein, “Money Shot – Blue Balls” (2017), acrylic and oil on canvas, 104 x 90 1/2 inches Our eyes adjust at different speeds to the dark. -

AWOL ERIZKU New Flower | Images of the Reclining Venus

PRESS CONTACT: Maureen Sullivan Red Art Projects, 917.846.4477 [email protected] AWOL ERIZKU New Flower | Images of the Reclining Venus Exhibition Dates: September 17 – December 12, 2015 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 17, 6-8PM NEW YORK, NY – The FLAG Art Foundation presents Awol Erizku: New Flower | Images of the Reclining Venus from September 17 – December 12, 2015, on FLAG’s 10th floor gallery. The exhibition marks the first presentation of the artist’s series of photographs taken in Ethiopia’s capital city of Addis Ababa in 2013. This compelling body of portraiture challenges the mythologized art historical role of the Venus and the odalisque1 in Western painting, setting these tropes against the reality of one of the largest concentrations of sex workers in Africa2. A ‘Conceptual Mixtape’ by Erizku, produced in collaboration with Los Angeles-based DJ SOSUPERSAM, will be released alongside New Flower | Images of the Reclining Venus, featuring music, recorded conversations, and spoken word expanding on the ideas of the exhibitions. Awol Erizku has created several bodies of work re-contextualizing iconic art historical images through his cross-disciplinary approach to sculpture, photography, music, video installation, and social media channels, to discuss identity and the politics of representation. Erizku states “Growing up going to the MoMA or the Met, and not seeing enough people of color (in the art or in the museum)…I felt that there was something missing. So when I was ready to make work as art, I wanted to comment and critique the art history, and make art that reflected the environment I grew up around…” The exhibition’s title New Flower is the English translation of Addis Ababa, where Erizku created the series, made possible by the Alice Kimball Fellowship Award from Yale University, where he received his MFA. -

Hard Work: Lee Lozano's Dropouts

Hard Work: Lee Lozano’s Dropouts* JO APPLIN In April 1970, Lee Lozano put down her tools for good. With Dropout Piece, Lozano marked the end of a ten-year career in New York as a painter and con- ceptual artist, during which she produced an eclectic body of work in diverse media and achieved significant success.1 Lozano’s dropout had its roots in General Strike Piece of 1969, which involved the artist recording her “gradual but determined” withdrawal from the New York art world over the course of that summer. In August 1971, Lozano embarked upon a further strike action to sup- plement Dropout Piece: her “boycott of women,” which required that she cease all contact with other women. Although the boycott was planned only as a six- month-long experiment, after which she hoped her relations with women would be “better than ever,” for the rest of her life Lozano acknowledged other women only when compelled to do so.2 Waitresses, her friend Sol LeWitt would later recall, could expect Lozano to ignore them completely.3 * Versions of this paper have been presented at a number of institutions, and I would like to thank the organizers and audiences at each for their helpful comments and feedback. For their expert commentary, advice, and encouragement during the preparation of this paper, I would like to thank especially Briony Fer, Tamar Garb, Jaap van Liere, Lucy R. Lippard, Iris Müller-Westermann, Mignon Nixon, Barry Rosen, Richard Taws, and Anne M. Wagner. I am very grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for the award of a Philip Leverhulme Prize, which enabled me to undertake research for this project. -

17 JUDITH BERNSTEIN Interviewed by Jonathan Thomas

JUDITH BERNSTEIN interviewed by Jonathan Thomas Judith Bernstein, Rising, installation view: Studio Voltaire, 2014 Jonathan Thomas: It’s snowing—and of women. I was very much aware of the fact there’s a parade outside. that there were only three women in my class Judith Bernstein: Yes, it’s a good omen; and that the rest were men. The instructors we’ve started on the Chinese New Year! were all men, except for Helen Frankenthaler, Thomas: Okay, this sounds a bit crazy. who was a visiting instructor and only taught a Bernstein: I see, there’s a disclaimer single course. At the orientation address, Jack already. What’s going on here? Tworkov, who was Chair of the School of Art, Thomas: I was going to say that for its said We cannot place women. What he meant to first 268 years, Yale University only accepted say was, If you’re a woman, you’re on your own students if they were men. after you graduate. We can’t help you get a job Bernstein: That’s correct. in an academic setting. That was day one, but Thomas: So when you were there as a it just went in one ear and out the other. Times graduate student from 1964 to 1967, women have changed. Now there are more women at were not permitted to attend as undergradu- Yale than men. ates, only men. That changed in 1969, but I’m Thomas: And the cost of getting an MFA wondering what it was like for you as a student has changed too. -

Press Kit Michael Stevenson Zeros and Ones Stanley Brouwn Content

Press Kit Michael Stevenson Zeros and Ones stanley brouwn Content Press Release Michael Stevenson Disproof Does Not Equal Disbelief Exhibition Text Biography Public Program Zeros and Ones Exhibition Text Public Program stanley brouwn Exhibition Text Education and Art Mediation General Information For image requests and text material, please contact our press oFFice. As oF: June 1, 2021 / Subject to change Press Contact KW Institute for Contemporary Art Natanja von Stosch Tel. +49 30 243459 41 [email protected] KW Institute For Contemporary Art KUNST-WERKE BERLIN e. V. Auguststr. 69 10117 Berlin kw-berlin.de Facebook.com/kwinstituteForcontemporaryart instagram.com/kwinstituteFcontemporaryart 1/3 Press Release Berlin, June 9, 2021 KW Institute for Contemporary Art presents its summer program 2021 KW Institute for Contemporary Art is pleased to announce its program for summer 2021. This season explores the organizational structures that shape our lived realities through a solo exhibition by Michael Stevenson, the simultaneous group exhibition Zeros and Ones, curated with the artist Ghislaine Leung, and a showing of works by stanley brouwn. All three of these exhibitions view the world through the lens of scripts and scores—revealing the formulas that condition us, both within the parameters for art and beyond, in the face of the driving ideological, political, and economic forces of our lives. Along with these exhibitions, KW launches Open Secret in mid July as part of its digital program. This six-month program investigates the hidden dimensions of technology and the role these play in our apparently “open society.” Furthermore, we will exhibit the final presentation of this year’s participants of the BPA// Berlin Program for Artists by the end of August. -

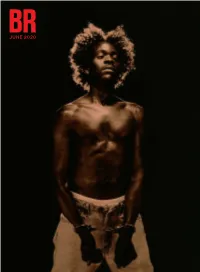

June 2020 June 2020 June 2020 June 2020

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 field notes art books Normality is Death by Jacob Blumenfeld 6 Greta Rainbow on Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects 88 Where Is She? by Soledad Álvarez Velasco 7 Kate Silzer on Excerpts from the1971 Journal of Prison in the Virus Time by Keith “Malik” Washington 10 Rosemary Mayer 88 Higher Education and the Remaking of the Working Class Megan N. Liberty on Dayanita Singh’s by Gary Roth 11 Zakir Hussain Maquette 89 The pandemics of interpretation by John W. W. Zeiser 15 Jennie Waldow on The Outwardness of Art: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes 90 Propaganda and Mutual Aid in the time of COVID-19 by Andreas Petrossiants 17 Class Power on Zero-Hours by Jarrod Shanahan 19 books Weston Cutter on Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League art and Luke Geddes’s Heart of Junk 91 John Domini on Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne ART IN CONVERSATION and Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s Seeing the Body: Poems 92 LYLE ASHTON HARRIS with McKenzie Wark 22 Yvonne C. Garrett on Camille A. Collins’s ART IN CONVERSATION The Exene Chronicles 93 LAUREN BON with Phong H. Bui 28 Yvonne C. Garrett on Kathy Valentine’s All I Ever Wanted 93 ART IN CONVERSATION JOHN ELDERFIELD with Terry Winters 36 IN CONVERSATION Jason Schneiderman with Tony Leuzzi 94 ART IN CONVERSATION MINJUNG KIM with Helen Lee 46 Joseph Peschel on Lily Tuck’s Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories 96 june 2020 THE MUSEUM DIRECTORS PENNY ARCADE with Nick Bennett 52 IN CONVERSATION Ben Tanzer with Five Debut Authors 97 IN CONVERSATION Nick Flynn with Elizabeth Trundle 100 critics page IN CONVERSATION Clifford Thompson with David Winner 102 TOM MCGLYNN The Mirror Displaced: Artists Writing on Art 58 music David Rhodes: An Artist Writing 60 IN CONVERSATION Keith Rowe with Todd B. -

High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967-1975 ______Traveling Exhibition Project Description

High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967-1975 _____________________________________________________________________________ Traveling Exhibition Project Description Dan Christensen, Pavo, 1968 Curated by Katy Siegel with David Reed as advisor Organized and circulated by iCI (Independent Curators International), New York Tour Dates: August 2006 to August 2008 High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967-1975 ________________________________________________________________________________ Project Description In the late 1960s the New York art world was, famously, an exciting place to be. New mediums such as performance and video art were developing, and sculpture was quickly expanding in many different directions. Experimental abstract painting that pressed the medium to its limits was an important part of the moment, and this exhibition recaptures its liveliness and urgency. All of this was happening during a politically and socially tumultuous time in the United States, a time when the art world, too, was changing under the impact of the civil rights struggle, student and anti-war activism, and the beginnings of feminism. Painting is the one element usually left out of this complex narrative, remembered only as a regressive foil to the various new mediums. But this version of the story greatly oversimplifies the situation, effacing painting that earned a place among the most experimental work of the moment, very much in sympathy with the era’s radical aesthetics and politics. This turbulent period is captured in High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967-1975, an exhibition that brings together approximately forty works by thirty-eight artists living and working in New York from 1967 to 1975. The exhibition is divided into five groups, with categories that are at once formal and chronological. -

SBU Art Exhibition, Gallery & Museum Spaces

SBU Archives: SBU Art Exhibition, Gallery & Museum Spaces Start Date End Date Event Title Artist(s): Last, First Location (from Catalog) Lom, Kiana; Schnell, Blake; Tabora, 2021-04-29 2021-05-19 Senior Show & URECA Art Exhibition 2021 Kevin; Calle, Nikola; Wang, Xiaohui Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Balius, Stuart; Cheng, Yifei; Baumiller, 2021-03-22 2021-04-16 Four: MFA Thesis Exhibition 2021 Marta; Waugh, Annemarie Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2021-02-01 2021-03-01 Reckoning: Student Digital Mural Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University (Online) 2020-10-01 2021-10-31 Reckoning: Faculty Exhibition 2020 Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University (Online) 2020-04-30 2020-05-22 Senior Show and URECA Art Exhibition Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2020-03-21 2020-04-18 MFA Thesis Exhibition 2020: Presence Absence Miller, Julia; Santarpia, Joseph Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Artists As Innovators: Celebrating Three Decades of 2019-10-26 2020-02-22 NYSCA/NYFA Fellowships Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2019-07-18 2019-10-12 View from Here: Contemporary Perspectives From Senegal, The Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2019-05-02 2019-05-15 Senior Show and URECA Art Exhibition Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Ruiz, Lauren; Avolio, Maggie; Kaiser, 2019-03-23 2019-04-18 MFA Thesis Exhibition 2019: Fold, Fragment, Forum Katherine Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Gannis, Carla; Leegte, Jan Robert; Louw, Gretta; Matsuda, Keiichi; Mundy, Owen; Rezaire, Tabita; Ross, Alicia; 2019-01-26 2019-02-23 Iconicity Warnayaka Art Centre; American Artist Paul W. -

Frieze London and Masters Find a Common Future for Contemporary

ARTSY EDITORIAL BY ALEXANDER FORBES OCT 4TH, 2017 7:18 PM critical dialogue and market trends that have increasingly blurred the distinction between "old" and "new." Take "Bronze Age c. 3500 BC-AD 2017," Hauser & Wirth's thematic booth at Frieze London, curated in collaboration with hipster feminist hero and University of Cambridge classics professor Mary Beard, whose fairly tongue-in-cheek descriptions of the works are worth a look. The mock museum brings together historic works by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Louise Bourgeois, and Henry Moore with contemporary artists from the gallery's program (Phyllida Barlow, who currently represents the U.K. at the Venice Biennale, made her first-ever piece in bronze, Paintsticks, 2017, for the occasion). These are interspersed with antiquities Beard helped source from regional museums and around 50 purported artefacts that Wenman bought on eBay. "Part of the irony is that it looks like a Frieze Masters booth," said Hauser & Wirth senior director Neil Wenman. "I wanted to bring old things but the lens is contemporary. It's about the way we look at objects," and how a given mode of display can ascribe value to those objects. The gallery hasn't leveraged the gravitas of its ethnographic museum vitrines to sell Wenman's eBay finds at a steep margin, but it is offering80 artworks for sale (out of the roughly 180 objects on display). For those on a budget, they've also created souvenirs sold from a faux museum gift shop that will run you £ 1-£9; proceeds will go to the four museums that lent pieces for the show.