Examining the Impact of Flying Buttresses and Other Innovative Strategies in High Gothic Cathedral Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paris, Brittany & Normandy

9 or 12 days PARIS, BRITTANY & NORMANDY FACULTY-LED INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS ABOUT THIS TOUR Rich in art, culture, fashion and history, France is an ideal setting for your students to finesse their language skills or admire the masterpieces in the Louvre. Delight in the culture of Paris, explore the rocky island commune of Mont Saint-Michel and reflect upon the events that took place during World War II on the beaches of Normandy. Through it all, you’ll return home prepared for whatever path lies ahead of you. Beyond photos and stories, new perspectives and glowing confidence, you’ll have something to carry with you for the rest of your life. It could be an inscription you read on the walls of a famous monument, or perhaps a joke you shared with another student from around the world. The fact is, there’s just something transformative about an EF College Study Tour, and it’s different for every traveler. Once you’ve traveled with us, you’ll know exactly what it is for you. DAY 2: Notre Dame DAY 3: Champs-Élysées DAY 4: Versailles DAY 5: Chartres Cathedral DAY 3: Taking in the views from the Eiff el Tower PARIS, BRITTANY & NORMANDY 9 or 12 days Rouen Normandy (2) INCLUDED ON TOUR: OPTIONAL EXCURSION: Mont Saint-Michel Caen Paris (4) St. Malo (1) Round-trip airfare Versailles Chartres Land transportation Optional excursions let you incorporate additional Hotel accommodations sites and attractions into your itinerary and make the Light breakfast daily and select meals most of your time abroad. Full-time Tour Director Sightseeing tours and visits to special attractions Free time to study and explore EXTENSION: French Riviera (3 days) FOR MORE INFORMATION: Extend your tour and enjoy extra time exploring your efcollegestudytours.com/FRAA destination or seeing a new place at a great value. -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

2019 Pilgrimage Through the French Monasticism Movement

2019 Pilgrimage through the French Monasticism Movement We invite you to pilgrimage through France to observe the French Monasticism movement, the lessons it holds for the church today and for your own personal spiritual growth. We will visit Mont St-Michel, stay in the monastery at Ligugé, spend a weekend immersed in the Taizé Community, and make stops in other historic and contemporary monastic settings. Our days and reflections will be shaped by both ancient and contemporary monastic practices. Itinerary Days 1 and 2 – Arrive Paris and visit Chartres We will begin our pilgrimage by traveling from the Paris airport to Chartres Cathedral where we will begin and dedicate our pilgrimage by walking the massive labyrinth laid in the floor of the nave just as pilgrims have done before us for nearly 800 years. We will spend the night in Chartres at The Hôtellerie Saint Yves, built on the site of an ancient monastery and less than 50 m from the cathedral. Day 3 and 4 – Mont-Saint-Michel and Ligugé In the morning, we will travel to the mystical islet of Mont-Saint-Michel, a granite outcrop rising sharply (to 256 feet) out of Mont-Saint-Michel Bay (between Brittany and Normandy). We will spend the day here and return on Sunday morning to worship as people have since the first Oratory was built in the 8th Century. After lunch on the mount we will head to Ligugé Monastery for the night. Day 5 – Vézelay Following the celebration of Lauds and breakfast at Ligugé, we will depart for the hilltop town of Vézelay. -

The Unifying Role of the Choir Screen in Gothic Churches Author(S): Jacqueline E

Beyond the Barrier: The Unifying Role of the Choir Screen in Gothic Churches Author(s): Jacqueline E. Jung Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, No. 4, (Dec., 2000), pp. 622-657 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3051415 Accessed: 29/04/2008 18:56 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Beyond the Barrier: The Unifying Role of the Choir Screen in Gothic Churches JacquelineE. Jung Thomas Hardy's early novel A Laodicean (first published in in church rituals, "anti-pastoral devices"4 designed to prevent 1881) focuses on the relationship between Paula Power, a ordinary people from gaining access to the sacred mysteries. -

The Analysis on the Collapse of the Tallest Gothic Cathedral

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The Analysis on the Collapse of the Tallest Gothic Cathedral Author: Seong-Woo Hong, Professor, Kyungwoon University Subject: Structural Engineering Keyword: Structure Publication Date: 2004 Original Publication: CTBUH 2004 Seoul Conference Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Seong-Woo Hong The Analysis on the Collapse of the Tallest Gothic Cathedral Seong-Woo Hong1 1 Professor, School of Architecture, Kyungwoon University Abstract At the end of the twelfth century, a new architectural movement began to develop rapidly in the Ile-de-France area of France. This new movement differed from its antecedents in its structural innovations as well as in its stylistic and spatial characteristics. The new movement, which came to be called Gothic, is characterized by the rib vault, the pointed arch, a complex plan, a multi-storied elevation, and the flying buttress. Pursuing the monumental lightweight structure with these structural elements, the Gothic architecture showed such technical advances as lightness of structure and structural rationalism. However, even though Gothic architects or masons solved the technical problems of building and constructed many Gothic cathedrals, the tallest of the Gothic cathedral, Beauvais cathedral, collapsed in 1284 without any evidence or document. There have been two different approaches to interpret the collapse of Beauvais cathedral: one is stylistic or archeological analysis, and the other is structural analysis. Even though these analyses do not provide the firm evidence concerning the collapse of Beauvais cathedral, this study extracts some confidential evidences as follows: The bay of the choir collapsed and especially the flying buttress system of the second bay at the south side of the choir was seriously damaged. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral. -

Mont Saint-Michel, France

Mont Saint-Michel, France The beautiful Mont Saint-Michel at night The timeless treasure of Mont Saint-Michel rises from the sea like a fantasy castle. This small island, located off the coast in northern France, is attacked by the highest tides in Europe. Aubert, Bishop of Avranches, built the small church at the request of the Archangel Michael, chief of the ethereal militia. A small church was dedicated on October 16, 709. The Duke of Normandy requested a community of Benedictines to live on the rock in 966. It led to the construction of the pre-Romanesque church over the peak of the rock. The very first monastery buildings were established along the north wall of the church. The 12th century saw an extension of the buildings to the west and south. In the 14th century, the abbey was protected behind some military constructions, to escape the effects of the Hundred Years War. However, in the 15th century, the Romanesque church was substituted with the Gothic Flamboyant chancel. The medieval castle turned church has become one of the important tourist destinations of France. The township consists of several shops, restaurants, and small hotels. Travel Tips Remember that the tides here are very rough. Do not try to walk over sand as it is dangerous. Get the help of a guide if you wish to take a stroll over the tidal mudflats. The Mount has steep steps; climb carefully. Mont St-Michel Location Map Facts about Mont St-Michel The Mont St-Michel and its Bay were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. -

Gothic Europe 12-15Th C

Gothic Europe 12-15th c. The term “Gothic” was popularized by the 16th c. artist and historian Giorgio Vasari who attributed the style to the Goths, Germanic invaders who had “destroyed” the classical civilization of the Roman empire. In it’s own day the Gothic style was simply called “modern art” or “The French style” Gothic Age: Historical Background • Widespread prosperity caused by warmer climate, technological advances such as the heavy plough, watermills and windmills, and population increase . • Development of cities. Although Europe remained rural, cities gained increasing prominence. They became centers of artistic patronage, fostering communal identity by public projects and ceremonies. • Guilds (professional associations) of scholars founded the first universities. A system of reasoned analysis known as scholasticism emerged from these universities, intent on reconciling Christian theology and Classical philosophy. • Age of cathedrals (Cathedral = a church that is the official seat of a bishop) • 11-13th c - The Crusades bring Islamic and Byzantine influences to Europe. • 14th c. - Black Death killing about one third of population in western Europe and devastating much of Europe’s economy. Europe About 1200 England and France were becoming strong nation-states while the Holy Roman Empire was weakened and ceased to be a significant power in the 13th c. French Gothic Architecture The Gothic style emerged in the Ile- de-France region (French royal domain around Paris) around 1140. It coincided with the emergence of the monarchy as a powerful centralizing force. Within 100 years, an estimate 2700 Gothic churches were built in the Ile-de-France alone. Abbot Suger, 1081-1151, French cleric and statesman, abbot of Saint- Denis from 1122, minister of kings Louis VI and Louis VII. -

What the Middle Ages Knew Gothic Art Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018

What the Middle Ages knew Gothic Art Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know 1 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Economic prosperity – Growing independence of towns from feudal lords – Intellectual fervor of cathedral schools and scholastics – Birth of the French nation-state 2 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Pointed arch (creative freedom in designing bays) – Rib vault (St Denis, Paris) – Flying buttress (Chartres, France) 3 (Suger’s choir, St Denis, Paris) What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Consequences: • High naves • Campaniles, towers, spires: vertical ascent • Large windows (walls not needed for support) • Stained glass windows • Light 4 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Consequences: • The painting (and its biblical iconography) moves from the church walls to the glass windows 5 What the Middle Ages knew • Architectural styles of the Middle Ages 6 Lyon-Rowen- Hameroff: A History of the Western World What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Consequences: • Stained glass windows (Chartres, France) 7 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic – 1130: the most royal church is a monastery (St Denis), not a cathedral – Suger redesigns it on thelogical bases (St Denis preserved the mystical manuscript attributed to Dionysus the Aeropagite) – St Denis built at the peak of excitement for the conquest of Jerusalem (focus on Jesus, the one of the three persons that most mattered to the crusaders) – St Denis built on geometry and arithmetics (influence of Arab -

Avignon Tourisme En Septembre 2019 En 2150 Exemplaires

2020 Avignon, your destination Vibrant, innovative, magical Individuals - Groups - Mice www.avignon-tourisme.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 DISCOVER the unmissable UNESCO world heritage site 4 THE PALACE OF THE POPES 5 THE BRIDGE OF AVIGNON 6 MUSEUMS 7 BE AMAZED by the wealth of heritage! 8 LEARN everything there is to know about wine. 9 ENJOY Provençale cuisine 10 BE BEWITCHED by a city that never stops 11 GO GREEN On Ile de la Barthelasse 12 REACH OUT From Avignon 18 GET A SURPRISE All year long 20 OUTSIDE AVIGNON Edition réalisée par Avignon Tourisme en septembre 2019 en 2150 exemplaires. 21 CHOOSE AVIGNON Maquette et mise en page : Agence Saluces - Avignon to host your bespoke events Impression : Rimbaud- Crédits photos – tous droits réservés : 21 Empreintes d’Ailleurs / E. Larrue / Coll. Blachère / COMING TO AVIGNON F. Olliver / E. Catoliquot / P. Bar / G. Quittard / Aurelio Avignon at your service 22 OPENING TIMES & PRICES Dans un souci de protection de l’environnement, ce guide est édité par un imprimeur IMPRIM’VERT. "# protection, this guide in printed by a green IMPRIM’VERT printer. unesco SITES DISCOVER the unmissable UNESCO world heritage site An old town at heart! Avignon has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1995 for its Historic Centre home to the Palais des Papes, Episcopal Ensemble with Avignon Cathedral, Petit Palais Museum, Pont d’Avignon and it ramparts, forming a mammoth and unique collection. UNESCO Charter In 2018, Arles and Avignon signed a charter to work together to promote their destina- tions to tourists based on the UNESCO World D104 Grotte Chauvet 2 Heritage theme. -

The Shrines of &

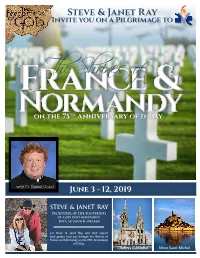

Steve & Janet Ray Invite you on a Pilgrimage to FranceThe Shrines of & Normandyth on the 75 Anniversary of d-day with Fr. Daniel Good June 3 - 12, 2019 STEVE & JANET RAY Producers of the Footprints of God documentaries; Int'l author & speaker Let Steve & Janet Ray and their expert local guides lead you through the Shrines of France and Normandy on the 75th Anniversary of D-Day. Chartres Cathedral Mont Saint Michel Pilgrimage to France with Steve & Janet Ray Planned Tentative Itinerary* You will be accompanied every day by Steve & Janet Ray along with their excellent Roman Catholic local guide. Day 1 : Monday, June 3, 2019 | Depart USA Depart on overnight flights to Paris, France. Day 2 : Tuesday, June 4, 2019 • Arrival in France | Lisieux | Pont-Audemer (D) Arrive at the Paris Airport and meet Steve & Janet Ray and your local French tour manager in the Arrivals Hall. Board your private motor coach for transfer to Lisieux, home of St. Therese, the “Little Flower”. Tour of the Basilica. Time for lunch on your own. Visit the “Buissonnets”, the family home where St. Therese spent her childhood and see the Carmelite convent where she lived until her death. Have time for prayer by her relics at her shrine. Visit the Cathedral of St. Peter where the Martin family went regularly for Mass. Celebrate Mass. Transfer to Pont-Audemer and check in to your hotel. Celebratory welcome dinner and overnight in Pont-Audemer. Note: Itinerary today pending actual flight arrival time. Day 3 : Wednesday, June 5, 2019 • Caen | Arromaches | Normandy Beaches (B|D) Breakfast at your hotel. -

Flying Buttress and Pointed Arch in Byzantine Cyprus

Flying Buttress and Pointed Arch in Byzantine Cyprus Charles Anthony Stewart Though the Byzantine Empire dissolved over five hundred years ago, its monuments still stand as a testimony to architectural ingenuity. Because of alteration through the centuries, historians have the task of disentangling their complex building phases. Chronological understanding is vital in order to assess technological “firsts” and subsequent developments. As described by Edson Armi: Creative ‘firsts’ often are used to explain important steps in the history of art. In the history of medieval architecture, the pointed arch along with the…flying buttress have receive[d] this kind of landmark status.1 Since the 19th century, scholars have documented both flying buttresses and pointed arches on Byzantine monuments. Such features were difficult to date without textual evidence. And so these features were assumed to have Gothic influence, and therefore, were considered derivative rather than innovative.2 Archaeological research in Cyprus beginning in 1950 had the potential to overturn this assumption. Flying buttresses and pointed arches were discovered at Constantia, the capital of Byzantine Cyprus. Epigraphical evidence clearly dated these to the 7th century. It was remarkable that both innovations appeared together as part of the reconstruction of the city’s waterworks. In this case, renovation was the mother of innovation. Unfortunately, the Cypriot civil war of 1974 ended these research projects. Constantia became inaccessible to the scholarly community for 30 years. As a result, the memory of these discoveries faded as the original researchers moved on to other projects, retired, or passed away. In 2003 the border policies were modified, so that architectural historians could visit the ruins of Constantia once again.3 Flying Buttresses in Byzantine Constantia Situated at the intersection of three continents, Cyprus has representative monuments of just about every civilization stretching three millennia.