Contextualizing the Influence of Cinema and Virtual Reality in Artificial Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Magic Kingdom Epcot Animal Kingdom Hollywood Studios

Magic Kingdom Animal Kingdom ● *Seven Dwarfs Mine Train Pick one from this group: ● *Peter Pan's Flight ● *Space Mountain ● *Avatar Flight of Passage ● *Meet Mickey Mouse at Town Square Theater ● *Nav'i River Journey ● *Splash Mountain ● *Enchanted Tales with Belle Then two more from these: ● Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ● Buzz Lightyear's Space Ranger Spin ● *Kilimanjaro Safaris ● Dumbo the Flying Elephant ● *Meet Favorite Disney Pals at Adventurer’s ● Haunted Mansion Outpost (Mickey & Minnie) ● "it's a small world" ● *Expedition Everest ● Jungle Cruise ● Dinosaur ● Mad Tea Party ● Festival of the Lion King ● Meet Ariel at Her Grotto ● Finding Nemo – The Musical ● Meet Cinderella/Elena - Princess Fairytale Hall ● It’s Tough to be a Bug! ● Meet Rapunzel/Tiana - Princess Fairytale Hall ● Kali River Rapids ● Meet Tinker Bell at Town Square Theater ● Primeval Whirl ● Mickey's PhilharMagic ● Rivers of Light ● Monster's, Inc. Laugh Floor ● UP! A Great Bird Adventure ● Pirates of the Caribbean ● The Barnstormer Hollywood Studios (effective 3/4/20) ● The Magic Carpets of Aladdin ● The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh Pick one from this group: ● Tomorrowland Speedway ● Under the Sea - Journey of the Little Mermaid ● *Slinky Dog Dash ● *Millenium Falcon: Smuggler’s Run Epcot ● *Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway Pick one from this "Tier One" group: Then two more from these: ● *Frozen Ever After ● *Toy Story Mania! ● *Soarin' ● *Rock 'n' Roller Coaster Starring Aerosmith ● *Test Track Presented by Chevrolet ● *The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror -

WDW Attractions

O N E P A G E G U I D E ANIMAL KINGDOM ATTRACTIONS TulipAndSnowflake.com ANIMAL KINGDOM PLANNING MADE EASY! Shows? Rides? Animal paths? What exactly is there to do at Disney’s Animal Kingdom? This one-page guide provides information to help you decide which attractions are right for your family, which ones require advanced planning or FastPass reservations, and what time of day you might want to enjoy each one. In addition to basic facts like minimum height requirements and FastPass availability, this guide indicates whether the queue and the attraction itself are indoors, outside, or covered. Use this information to determine which rides should be avoided in the afternoon heat and rain. Queue interest prepares you for boredom and help you decide which attractions you want to FastPass or only attempt with a short posted wait time to avoid a boring line. Wait indicators give you an idea of the line length that these attractions draw. The attraction types and descriptions provide a basic description of each attraction, how your family might be split up, and just how comfortable those theater seats may (or may not!) be. This guide does not include character meetings. Check the Times Guide in the park for character locations and meeting availability times. Let’s start planning your Animal Kingdom park day! Traci TulipAndSnowflake.com ANIMAL KINGDOM ATTRACTIONS GUIDE MIN QUEUE RIDE VEHICLE / ATTRACTION FP HEIGHT QUEUE ATTRACTION INTEREST WAIT TYPE ATTRACTION DESCRIPTION DISCOVERY ISLAND It's Tough to be a Bug! • any indoors -

WDW2020-Tink's Fastpass Tips

WALT DISNEY WORLD: FASTPASS+ TINK’S MAGICAL VACATIONS Fast Pass+ at Walt Disney World Disney FastPass+ service lets you reserve access to select attractions, entertainment and more! With the purchase of a ticket or annual pass, you can start making selections as early as 30 days before you arrive, or up to 60 days (huge benefit!) before check-in when you have a Walt Disney World Resort hotel reservation. There is no extra charge for this complimentary benefit. Before you start, be sure to link your vacation package, or tickets, or your annual pass to your MyDisneyExperience account. Also make sure to add the people you are planning with to your Friends and Family list. You can book up to 3 FastPass+ sixty days before your WDW check in date, starting at 7am in your MyDisneyExperience account. Tink’s recommends making your FastPass+ selections early in order to have a greater variety of options to choose from. After you have used up your first three FastPasses, you can get a 4th, use that up, you can get a 5th, etc. If your ticket includes a Park Hopper Option, after you use your initial FastPass+ selections at the first park, you’ll be able to make additional FastPass+ selections (one at a time) at the second park you visit that day, up to park closing. Just visit a kiosk or use your mobile device to make the additional selections. Note that kiosks allow FastPass+ selections only for the park where the kiosk is located, but you can view and cancel any of your FastPass+ selections, regardless of location. -

Walt Disney World: Fastpass+ Selection Guide with Height Restrictions

Walt Disney World: FastPass+ Selection Guide with Height Restrictions * Magic Kingdom * * Epcot * * Animal Kingdom * * Hollywood Studios * Ariel’s Grotto Barnstormer (35”) Group A (Choose One) Group A (Choose One) Group A (Choose One) Big Thunder Mountain Railroad (40”) Epcot Forever Avatar Flight of Passage (44”) Alien Swirling Saucers (32”) Buzz Lightyear’s Ranger Spin Frozen Ever After Na’vi River Journey Slinky Dog Dash (38”) Dumbo the Flying Elephant Soarin (40”) Toy Story Mania Enchanted Tales with Belle Test Track (40”) Group B (Choose Two) Twilight Tower of Terror (40”) Haunted Mansion DINOSAUR(40”) Rock’ n’ Roller Coaster (48”) it’s a small world Group B (Choose Two) Expedition Everest (44”) Jungle Cruise Disney & Pixar Short Film Festival Festival of the Lion King Group B (Choose Two) Mad Tea Party Journey into Imagination with Figment Finding Nemo the Musical Beauty and the Beast Live on Stage Magic Carpets of Aladdin Living with the Land It’s Tough to be a Bug Disney Junior Live on Stage Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh Mission Space (44”) Kali River Rapids (38”) Fantasmic! Mickey’s PhilharMagic Spaceship Earth Kilimanjaro Safaris For the First Time in Forever: A Frozen Monster’s Inc. Laugh Floor The Seas with Nemo & Friends Adventurers Outpost Sing Along Peter Pan’s Flight Turtle Talk with Crush Character Greeting Indiana Jones Epic Stunt Spectacular Pirates of the Caribbean Primeval Whirl (48”) Muppet Vision 3D Princess Fairy Tale Hall: Meet and Rivers of Light Star Tours: The Adventure Continues (40”) Greet Cinderella and Elena UP! A Great Bird Adventure Voyage of the Little Mermaid OR Rapunzel and Tiana Animation Experience at Seven Dwarf’s Mine Train (38”) Conservation Station NOTE: Millennium Falcon: Smugglers Run and Space Mountain (44”) Rise of the Resistance are not part of Splash Mountain (40”) Choose up to Three FastPasses per day - they all must be in the same park. -

Disney Parks, Experiences and Products Reveals Plans for D23 Expo, Aug

DISNEY PARKS, EXPERIENCES AND PRODUCTS REVEALS PLANS FOR D23 EXPO, AUG. 23-25, 2019 Guests will discover an immersive pavilion, entertaining presentations, and all-new merchandise. BURBANK, Calif. (July 17, 2019) – D23 Expo 2019 will be a must for fans of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products. An immersive pavilion will provide an insider’s look at new themed lands, attractions, shows, and more, in addition to a jam-packed schedule of entertaining presentations and a number of exclusive shopping opportunities for every Disney fan. Showcasing an array of new experiences for guests around the world to enjoy for years to come, the Disney Parks “Imagining Tomorrow, Today” pavilion will give fans a unique look at the exciting developments underway at Disney parks around the world. Attendees will see a dedicated space showcasing the historic transformation of Epcot at Walt Disney World Resort. They will also see Tony Stark’s latest plans to recruit guests to join alongside the Avengers in fully immersive areas filled with action and adventure in Hong Kong, Paris, and California. The fan-favorite Hall D23 presentation with Bob Chapek, chairman of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products, will take place Sunday, August 25, at 10:30 a.m. Guests will be treated to more details on much-anticipated attractions, experiences, and transformative storytelling that set Disney apart. During the three-day event, fans can scoop up never-before-seen collectibles across the Disney Parks, Experiences and Products-operated retail shops on the Expo floor: shopDisney.com | Disney Store, Disney DreamStore, Mickey’s of Glendale, and Mickey’s of Glendale Pin Store. -

21 Ways to Kick Off 2021 with Magic at Walt Disney World Resort

21 Ways to Kick Off 2021 with Magic at Walt Disney World Resort LAKE BUENA VISTA, Fla. (Jan. 1, 2021) – Walt Disney World Resort is ready to help guests make the new year magical. From new and classic attractions to culinary experiences to character interactions and more, The Most Magical Place on Earth has plenty to offer those wanting to immediately turn the page on 2020. Here are 21 reasons to be excited about a visit to Walt Disney World in early 2021: 1. Explore the Taste of EPCOT International Festival of the Arts, Beginning Jan. 8 – Through Feb. 22, guests are invited to an expansive collection of visual, performance and culinary arts throughout the park. 2. Gaze Upon the Reimagined Entrance Fountain at EPCOT – The new water feature in front of Spaceship Earth hearkens back to the park’s origins and highlights a greener, more open and welcoming entry experience for guests. The fountain is the most recent milestone in the historic transformation of EPCOT now underway. 3. Step Inside the Cartoon World of Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway at Disney’s Hollywood Studios – Guests go through the movie screen as Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Engineer Goofy and Pluto take them on a trip through Runnamuck Park … where anything can happen! 4. Embark on a Star Wars Adventure in a Galaxy Far, Far Away – Disney’s Hollywood Studios is also home to Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, the immersive, award-winning land featuring two thrilling attractions: Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance and Millennium Falcon: Smugglers Run. 5. Check Out Cinderella Castle’s Royal Makeover – The treasured icon at the heart of Magic Kingdom Park now features bold, shimmering and regal enhancements befitting its royal status, making for a great photo with family and friends. -

Star Wars: Galaxy's Edge

Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge – In Their Own Words How Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge Redefines What a Disney Experience Can Be Scott Trowbridge, Star Wars Portfolio Creative Executive, Walt Disney Imagineering “Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge redefines what a Disney experience can be. It invites exploration and discovery, where we can become characters in the Star Wars galaxy. More and more, our guests want to lean into these stories; not just be a spectator. We’re giving them the opportunity to do just that in this land, with a new level of detail and immersion. This is an opportunity to play and engage with your friends and family in a shared experience that will forge lifelong memories.” At Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, Guests Get to Change the Course of the Galaxy Scott Trowbridge, Star Wars Portfolio Creative Executive, Walt Disney Imagineering “At the heart of Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge is this fundamental truth: We all have the power to be a hero, making choices that change the course of the galaxy. Whether you’re a lowly moisture farmer on some remote planet or an orphan sitting in a pile of dirt just trying to scrape by, every individual has the power to change the universe.” What Makes a Place Feel Like Star Wars Doug Chiang, Vice President and Executive Creative Director, Lucasfilm “In designing the Star Wars universe, we don’t consider it science fiction or fantasy – we think of it more as a period piece, and we look at it almost from a documentary point of view. -

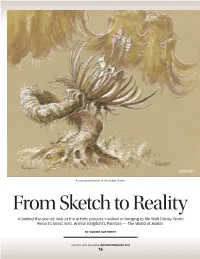

From Sketch to Reality, by Connie Sue White

A conceptual sketch of the Goblin Thistle. From Sketch to Reality A behind-the-scenes look at the artistic process involved in bringing to life Walt Disney World Resort’s latest land, Animal Kingdom’s Pandora — The World of Avatar. BY CONNIE SUE WHITE ORLANDO ARTS MAGAZINE JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018 16 P. 16-19 From Sketch to Reality.indd 16 12/11/17 3:24 PM The passiflora-topped Goblin Thistle grows in a hunched shape and is supported by propped roots in the Valley of Mo’ara at Pandora – The World of Avatar. During the evening bioluminescence, the thistle’s stooped appearance is more pronounced. There are at least 12 Goblin Thistles in Mo’ara. Some of the land’s floating mountains can be seen in the background. rederic Church. Gian Lorenzo Bernini. sci-fi Avatar, Disney’s fictional eco-centric land is Giovanni Battista Piranesi. It may come as a conflict-free, emphasizing the immersive experience surprise to some that stylistic quotations of of Pandora’s Valley of Mo’ara and its two rides: Avatar each of these masters, among others, are alive Flight of Passage, a 3-D simulated ride on the back of a Fand well in Walt Disney World Resort’s latest land, banshee, and the Na’vi River Journey, a “dark” ride Animal Kingdom’s Pandora — The World of Avatar. that takes guests through Pandora’s exotic biolumi- Art history is key when creating a land like Pandora nescent rainforest populated by majestic creatures. in a theme park that is stylistically realistic and not “The world of art history becomes the artists’ refer- fantasy — one that focuses on animals, wildlife ence library for approaching key design problems conservation and the environment. -

Motion Simulator Filmography

Master Class with Douglas Trumbull: Selected Films Created for Motion-Simulator Amusement Park Attractions *mentioned or discussed during the master class ^ride designed and accompanying film directed by Douglas Trumbull Despicable Me: Minion Mayhem. Dir. unknown, 2012, U.S.A. 8 mins. Production Co.: Universal Creative / Illumination Entertainment. Location: Universal Studios Florida; Opened 2012, still in operation, 2012. Star Tours: The Adventures Continue. Dir. unknown, 2011, U.S.A. 5 mins. Production Co.: Lucasfilm / Walt Disney Imagineering. Locations: Disney’s Hollywood Studios (Walt Disney World Resort), Disneyland Anaheim, Tokyo Disneyland; Opened 2011, still in operation, 2012 (Tokyo ride under construction). Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey. Dir. Thierry Coup, 2010, U.S.A. 5 mins. Production Co.: Universal Creative. Locations: Islands of Adventure, Universal Studios Japan, Universal Studios Hollywood; Opened 2010 (Islands of Adventure), ride is under construction at other parks. The Simpsons Ride. Dirs. Mike B. Anderson and John Rice, 2008, U.S.A. 5 mins. Production Co.: 20th Century Fox Television / Reel FX Creative Studios / Blur Studio / Gracie Films / Universal Creative. Location: Universal Studios Florida, Universal Studio Hollywood; Opened 2008, still in operation, 2012. Jimmy Neutron’s Nicktoon Blast. Dir. Mario Kamberg, 2003, U.S.A. 5 mins. Production Co.: Nickelodeon Animation Studios / Universal Creative. Location: Universal Studios Florida; Opened 2003, closed 2011. Mission: SPACE. Dir. Peter Hastings, 2003, U.S.A. 5 mins. Production Co.: Walt Disney Imagineering. Location: Epcot (Walt Disney World Resort); Opened 2003, still in operation, 2012. Soarin’ Over California. Dir. unknown, 2001, U.S.A. 5 mins. Production Co.: Walt Disney Pictures. Location: Disney California Adventure, Epcot (Walt Disney World Resort); Opened 2001, still in operation, 2012. -

Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Announces New Lands, Entertainment and Experiences at D23 EXPO 2015

IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD: https://www.RelayIt.net/?c=mzcGntz5tpHPnJzmHBbJ4 B2DMFdvkHnR5Bp3 Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Announces New Lands, Entertainment and Experiences at D23 EXPO 2015 Star Wars, Toy Story Land, Pandora – The World of AVATAR, Soarin’ and Iron Man among new experiences coming for guests ANAHEIM, Calif. (Aug. 15, 2015) – Today, Disney announced a line- up of new attractions and entertainment coming to its theme parks around the world during the D23 EXPO 2015 in Anaheim, Calif. Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Chairman Bob Chapek gave 7,500 lucky fans a behind-the-scenes look at what’s to come. He was joined by Imagineers working on these projects as well as legendary filmmakers James Cameron and Jon Landau who shared new details about Pandora – The World of AVATAR including the names of the land and E-ticket attraction – AVATAR Flight of Passage. Fans also got a chance to see Marvel legend Stan Lee in a cameo appearance where he posed as an unsuspecting fan during Iron Man’s dramatic entrance. Among the many announcements Chapek shared were new and enhanced Star Wars experiences coming later this year to the Florida and California theme parks, plans for a new Toy Story Land at Disney’s Hollywood Studios, and more details on Pandora—The World of AVATAR, which is already under construction at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Chapek also shared that Soarin’ Around the World will make its U.S. film debut at Epcot and Disney California Adventure taking guests to new places around the world. Additionally, fans got a preview of exclusive video of the first Marvel attraction planned for Disney parks, coming to Hong Kong Disneyland in 2016. -

SUMMER 2010 Vol. 19 No. 2

SUMMER 2010 vol. 19 no. 2 Disney Files Magazine is published by the good people at With all due respect to the tried and true, I’ve long been obsessed with all things Disney Vacation Club ® new. (Don’t worry. I’m not going to rhyme this whole column. That was Dr. Suess’ P.O. Box 10350 Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830 gig, and I’m not a poet. Or a doctor.) This is more than a mere tendency. It’s an outright affliction. I once bought a “NEW” rain-gutter-cleaning tool from an in-flight catalog, which would’ve come in All dates, times, events and prices handy if my house actually had rain gutters. printed herein are subject to And it’s not just a problem at 30,000 feet. Asking me to walk past a new product change without notice. (Our lawyers in the grocery store without reaching for my wallet is like asking a cat to walk past a do a happy dance when we say that.) wounded finch without giving it a little nibble. The cat won’t listen, and neither will I. There must be a support group somewhere for people like me. It doesn’t help that I work in a role that encourages this behavior. I actually get MOVING? Update your mailing address paid to write about all that’s new here in the house of mouse. Pretty indulgent gig for online at www.dvcmember.com someone in my condition. Even if I had managed to kick the habit, this edition of Disney Files Magazine would’ve pushed me off the wagon.