RRTA 475 (26 June 2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transnational Indian Community in Manama, Bahrain

City of Strangers: The Transnational Indian Community in Manama, Bahrain Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Gardner, Andrew M. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 14:12:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195849 CITY OF STRANGERS: THE TRANSNATIONAL INDIAN COMMUNITY IN MANAMA, BAHRAIN By Andrew Michael Gardner ____________________________ Copyright © Andrew Michael Gardner 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Andrew M. Gardner entitled City of Strangers: The Transnational Indian Community in Manama, Bahrain and recommended that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Linda Green __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Tim Finan __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Mark Nichter __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Michael Bonine Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Download Article

Religion, Identity and Citizenship The Predicament of Shia Fundamentalism in Bahrain Abdullah A. Yateem In 2011, Bahrain witnessed an unprecedented wave of political protests that came within a chain of protest movements in other Arab coun- tries, which later came to be known as the “Arab Spring.” Irrespective of the difference in the appellations given to these protests, their oc- currence in Bahrain in particular poses a number of questions, some of which touch upon the social and political roots of this movement, especially that they started in Bahrain, a Gulf state that has witnessed numerous political reformation movements and democratic transfor- mations that have enhanced the country’s social and cultural openness in public and political life. Despite this pro-democratic environment, the political movement rooted in Shi’a origins persisted in developing various forms of political extremism and violence, raising concerns among Sunni and other communities. This work evaluates the origins of Shi’a extremism in Bahrain. Keywords: Middle East, Bahrain, Shi’a fundamentalism, Islam, Arab Spring, violence, Iran In the course of the year 2011, Bahrain witnessed an unprecedented wave of political protests,1 and that came within a chain of protest movements in other Arab countries, which later came to be known as the “Arab Spring”. The names that have been, and are still being, given Scan this article to the Bahrain protests were widely varied: “revolution,” “terror,” “up- onto your rising,” “ordeal,” “protests,” “crisis,” depending on the -

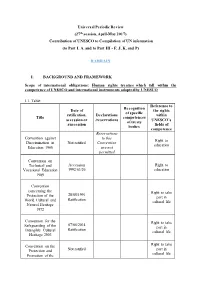

Universal Periodic Review (27Th Session, April-May 2017) Contribution of UNESCO to Compilation of UN Information (To Part I

Universal Periodic Review (27th session, April-May 2017) Contribution of UNESCO to Compilation of UN information (to Part I. A. and to Part III - F, J, K, and P) BAHRAIN I. BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORK Scope of international obligations: Human rights treaties which fall within the competence of UNESCO and international instruments adopted by UNESCO I.1. Table: Reference to Recognition Date of the rights of specific ratification, Declarations within Title competences accession or /reservations UNESCO’s of treaty succession fields of bodies competence Reservations Convention against to this Right to Discrimination in Not ratified Convention education Education 1960 are not permitted Convention on Accession Right to Technical and Vocational Education 1992/03/26 education 1989 Convention concerning the Right to take 28/05/1991 Protection of the part in Ratification World Cultural and cultural life Natural Heritage 1972 Convention for the Right to take 07/06/2014 Safeguarding of the part in Ratification Intangible Cultural cultural life Heritage 2003 Convention on the Right to take Protection and Not ratified part in cultural life Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2005 II. Input to Part III. Implementation of international human rights obligations, taking into account applicable international humanitarian law to items F, J, K, and P Right to education 1. NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK 1.1. Constitutional Framework 1. The Constitution (adopted on 14 February 2002)1 stipulates in its Article 7 that: (a) the State […] guarantees educational and cultural services to its citizens. Education is compulsory and free in the early stages as specified and provided by law. The necessary plan to combat illiteracy is laid down by law. -

The Development of Education National Report

The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) KINGDOM OF BAHRAIN MINISTRY OF EDUCATION THE DEVELOPMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL REPORT OF THE KINGDOM OF BAHRIAN (INCLUSIVE EDUCATION: THE WAY OF THE FUTURE) Presented to the Forty-Eight Session of the International Conference on Education (ICE) Geneva, 25-28 November 2008 Bahrain 2008 1 The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) 2 The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) H. H. Sheikh Khalifa H.M King Hamad Bin H.H Sheikh Salman Bin Bin Salman Al Khalifa Isa Al Khalifa Hamad Al Khalifa The Prime Minister The King of the The Crown prince Kingdom Deputy Supreme Commander of the BDF 3 The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) Report Team Work General Supervision and Edited By: Faeqa Saeed AlSaleh Asst. Under-Secretary for Planning and Information Team Work Ali Salman Zuhair Acting, Head of Handicapped and Talented Section-Directorate of Special Education Amina Abdulla Kamal Acting, Head of Learning Difficulties Section-Directorate of Special Education Layla Ali AlMulla Head of Compulsory Education Unit-General and Technical Education Sector Suliman Mahmood Suliman Head of Financial Auditing-Directorate of Financial Resources Khaled Mohammed AlJawder Acting, head of Educational Planning-Directorate of Educational -

49Th BAHRAIN NATIONAL DAY

An EngineEngine for for economic growtheconomic growth At Tamkeen, we not only encourage Businesses and Bahraini individuals but empower them through diversified solutions which directly lead to economic development. Our primary objectives are to foster the development and growth of enterprises, and provide support to enhance the productivity and training of the national workforce. 2 Bahrain National Day 2020 cover4 pages.indd 4 12/15/20 11:17 AM An EngineEngine for for economic growtheconomic growth 75 Years of At Tamkeen, we not only encourage Businesses and Bahraini individuals but empower them through Luxury diversified solutions which directly lead to economic development. Our primary objectives are to foster the development and growth of enterprises, and provide support to enhance the productivity and training he largest Rolex Boutique in the of the national workforce. Middle East, the Modern Art Studio and Rolex boutique was meticulously over 30 years. In addition to being the largest Art Studio at the time, Heiniger proclaimed designed to embrace Arabian heritage one in the Middle East, it is also one of the it “one of the best Rolex shops in the while maintaining the exclusivity largest Rolex boutiques in the world. world.” One of its notable showcases was synonymous with the Swiss watchmaker, serving The story of Modern Art Studio dates back a display of the exclusive watches cleverly T arranged into individual letters to spell the its discerning clientele from its accessible location to 1936, when its founder Naji Murad had his in City Centre Bahrain. original shop in Government Avenue, Manama. name ROLEX. Today, Modern Art Studio The boutique, which features an exclusive VIP By 1940, history was made when the founder maintains its legacy as a family business suite for private viewings, offers a one-of-a-kind of Rolex Geneva, Hans Wilsdorf, officially as it continues to operate under the wise experience for visitors. -

Media Implications in Bahrain's Textbooks in Light of UNESCO's

Journal of Social Studies Education Research Sosyal Bilgiler Eğitimi Araştırmaları Dergisi 2017:8 (3), 259-281 www.jsser.org Media Implications in Bahrain’s Textbooks in Light of UNESCO's Media Literacy Principles Fawaz Alshorooqi1 & Saleh Moh'd Rawadieh2 Abstract This study aims to identify the media implications of textbooks in the Kingdom of Bahrain in light of the principles of media literacy emanating from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The study is based on the textbooks of Arabic Language and Education for Citizenship for the sixth primary, third intermediate and third secondary schools in the Kingdom of Bahrain for the academic year 2015/2016. The two researchers chose the descriptive and analytical approach to identify the media implications included in the selected textbooks. While conducting their study, the two researchers analyzed the implications of these textbooks based on the principles of media literacy stemming from UNESCO and its three fields, namely: knowledge and understanding of the media implications, assessment of media implications, and creation and use of media implications. The study revealed that these textbooks contained 168 media implications, with many of them concentrated in the field of knowledge and understanding of media implications. Assessment of media implications, and its creation and use came second and third, respectively. In fact, the study particularly revealed that the implications relating to the knowledge of the role of the media in democratic societies and the content of assessing the development of media implications are the most prevalent in the various analyzed school textbooks. This significant finding is highly important from a curricular perspective. -

Documents on Education Development

DocumentsDocuments onon EducatioEducationn DevelopmentDevelopment AfricaAfrica,, MiddlMiddlee East,East, AsiaAsia,, Pacific,Pacific, thethe Americas,Americas, EuropeEurope IDC PUBLISHER SS IDCIDC PublishersPublishers offersoffers a broadbroad rangerange ofof editionseditions foforr ththee disciplinesdisciplines ooff EconomicsEconomics,, StatisticsStatistics andand SocialSocial Sciences.Sciences. FilmedFilmed inin closeclose cooperationcooperation withwith thethe Joint Bank FundFund LibraryLibrary inin WashingtonWashington DC,DC, thesethese editionseditions makemake availableavailable seriesseries ofof officialofficial statistics,statistics, planninplanningg documentsdocuments,, anandd progressprogress reports.reports. InIn manymany cases,cases, IDIDCC PublisherPublisherss offerofferss remarkablremarkablee runrunss ooff thesthesee datadata,, spanninspanningg severaseverall decadedecadess ofof social-economicsocial-economic planningplanning anandd performance.performance. ContentsContents HowHow toto orderorder Africa .....................................................................................................1.1 MiddlMiddlee EasEastt / NortNorthh AfricAfricaa .................................................................1010 PleasePlease sensendd youyourr ordeorderr to the followinfollowingg address:address: EasEastt AsiaAsia ............................................................................................. I1 1l IDIDCC PublisherPublisherss SoutSouthh AsiaAsia ..........................................................................................1313 -

Dr. Mike Diboll: Reflections on My Practice in Bahrain

Reflexive Education, Revolution, and Counter-Revolution: Reflections on my experiences in Bahrain Dr Mike Diboll This reflection arises out of my experience working in education reform in Bahrain during the politically fraught years between 2007 and 2011, and is informed by the concept of ‘reflective practice’ pioneered during the 1970s by MIT educationalist Donald A. Schön, and described in his influential 1983 book The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Since Schön, Education development can been seen as partaking in a new, ‘reflexive’, or ‘second’ modernity, towards which the post-colonial polities of the Arab world are transitioning. Thus, the tensions between the ‘classic institutions’ of the region’s ‘first’ modernity,1 post-colonial states and the expectations of the younger generations whose subjectivities have in part been shaped by ‘reflexive modernity’ change-drivers, ‘super-modernizing forces’, forms part context of the current political contestations on-going in the Arab world since 2011. Similarly, education partakes in the co-construction and mediation of new identities and new forms of political consciousness in ways that were not predicted by the ruling regimes. This leads to the displacement of the post-colonial state’s ‘determinate rules’ as increasingly autonomous citizens assuming the role of ‘rule-seekers’ exercising ‘reflective judgement.’2 I had worked in higher education in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region since 2002. My first degree had been in Arabic, and prior to my work in the GCC, I had worked in Cairo, and travelled extensively in the region. I worked at the College of Arts, University of Bahrain (UoB), 2007-8, and was involved in the start-up of Bahrain Teachers’ College (BTC). -

A Brief History of Discrimination Against Bahara in Bahrain

A BRIEF HISTORY OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST BAHARA IN BAHRAIN A Brief History of Discrimination Against Baharna In Bahrain Eman AbdulZahra A Major Research Paper submitted to the Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Women’s Studies Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada January 8th, 2020 A BRIEF HISTORY OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST BAHARNA IN BAHRAIN Dedication To the people who worshipped Awal in Akkadian, fought alongside Imam Ali (as) with pure intentions, and now, bow to no one but Allah . And to my mother, for being my guardian angel. My father, for his support. My partner, for his patience and relentless love. i A BRIEF HISTORY OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST BAHARNA IN BAHRAIN Abstract The Baharna people, at the hands of Al Khalifa, have had their lands taken, their title as to Bahrain erased, and their jobs limited. This paper explores the hidden history of the slavery (sukhra) of the Baharna, the discriminatory taxes enforced against them, and how security apparatus then and now monitor and never hesitate to use physical force to enforce the law. The women’s movement is also crucial to the understanding of the status of the Baharna, as Bahraini women are also lower-class citizens, especially in terms of inheritance, divorce and marriage laws and practices. ii A BRIEF HISTORY OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST BAHARNA IN BAHRAIN Table of Content Introduction p.1 Significance of the Research p.1 Overview of the Paper p.1 Framework -

Gender, Education and Development - a Partially Annotated and Selective Bibliography - Education Research Paper No

Education research gender, education and development - A partially annotated and selective bibliography - Education Research Paper No. 19, 1997, 250 p. Table of Contents Colin Brock (University of Oxford) Nadine Cammish (University of Hull) with Ruth Aedo- Richmond, Aparna Narayanan and Rose Njoroge January 1997 Reprinted January 1999 Serial No. 19 ISBN: 0902500767 Department For International Development Table of Contents Department for International Development - Education papers Acknowledgements Introduction Global Annotations Sub-Saharan Africa Individual countries Angola Benin Botswana Burkina Faso Cameroon Chad Congo Eritrea Ethiopia Gambia Ghana Guinea Guinea Bissau Ivory Coast Kenya Lesotho Liberia Madagascar Malawi Mali Mauritania Mozambique Namibia Niger Nigeria Rwanda Senegal Sierra Leone Somalia South Africa Sudan Swaziland Tanzania Togo Uganda Zaire Zambia Zimbabwe Annotations - Sub-Saharan Africa Individual countries Zimbabwe Sudan Niger Nigeria Ivory Coast Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe North Africa and Middle East Individual Countries Algeria Bahrain Cyprus Egypt Iran Iraq Jordan Kuwait Lebanon Libya Morocco Oman Palestine Qatar Saudi Arabia Syria Tunisia Turkey United Arab Emirates Yemen Annotations Individual countries Bahrain Saudi Arabia Asia Annotation South Asia Individual countries Afghanistan Bangladesh Bhutan India Nepal Pakistan Sri Lanka Annotations Individual countries Bangladesh India Pakistan Sri Lanka South East Asia Brunei Cambodia Indonesia Laos Malaysia Myanmar Papua New Guinea Phillipines Singapore Thailand -

Engineering Education in Bahrain

Session No 3460, Wednesday, June 23, 2004 Engineering Education in Bahrain Hisham Shihaby Bahrain Society of Engineers Role of Bahrain Society of Engineers in Continuing Education ABSTRACT One of the main objectives of the Bahrain Society of Engineers is to serve engineers, the profession and the community at large. The society started offering its members financial assistance to attend conferences outside Bahrain and went further to partly- finance members applying for graduate studies. More recently, The society has established a training centre offering a variety of courses not only to its members but also to the engineering community throughout the gulf region. This paper will outline the contribution of the Society to continuing engineering education. Background Formal primary education was launched in 1919 through the initiative of a group of enlightened Bahrainis who formed what was then known as the National Committee for Education. Prior to that there were a few private schools with a small student intake & traditional Quoran Learning Centres which offered a limited number of places for both male & female attendees. To start with formal primary education was limited to male students, females had to wait until 1928 when the first all females primary school was inaugurated. By 1930, the duties and responsibilities of the National Committee for Education were taken over by the government of Bahrain. The first batch of the primary school graduates, six male students, were sent to Beirut –Lebanon- to continue their education. Secondary education for males was started in 1940 & for females in 1951. The government, recognizing the need for trained technicians, established the first technical school in 1937. -

Bahrain's Third Cycle

Bahrain’s Third Cycle UPR Cycle Third Bahrain’s Bahrain’s Third Cycle UPR A RECORD OF REPRESSION A comprehensive assessment of the Bahraini government’s implementation of its second-cycle United Nations Universal Periodic Review recommendations, with analysis and of Repression A Record recommendations for the third cycle. ADHRB BIRD BCHR www.adhrb.org Bahrain’s Third Cycle UPR A RECORD OF REPRESSION January 2017 ADHRB – BCHR - BIRD ©2017, Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB), Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), and the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR). All rights reserved. Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain is a non-profit, 501(c) (3) organization based in Washington, D.C. We seek to foster awareness of and support for democracy and human rights in Bahrain and the Middle East. The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy is a London, UK based non-profit organization focusing on advocacy, education and awareness for the calls of democracy and human rights in Bahrain. The Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR) is a non-profit, non-governmental organization, registered with the Bahraini Ministry of Labor and Social Services since July 2002. Despite an order by the authorities in November 2004 to close, the BCHR is still functioning after gaining wide local and international support for its struggle to promote human rights in Bahrain. Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain 1001 Connecticut Ave. Northwest, Suite 205 Washington, DC 20036 202.621.6141 www.adhrb.org Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy www.birdbh.org Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR) www.bahrainrights.org Design and layout by Jennifer Love King Assessment of the Recommendations SECTION A Criminal Justice PAGE 10 1.