Comparing Perceptions of School Principal Effectiveness in the Kingdom of Bahrain with the U.S. Principalship Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transnational Indian Community in Manama, Bahrain

City of Strangers: The Transnational Indian Community in Manama, Bahrain Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Gardner, Andrew M. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 14:12:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195849 CITY OF STRANGERS: THE TRANSNATIONAL INDIAN COMMUNITY IN MANAMA, BAHRAIN By Andrew Michael Gardner ____________________________ Copyright © Andrew Michael Gardner 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Andrew M. Gardner entitled City of Strangers: The Transnational Indian Community in Manama, Bahrain and recommended that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Linda Green __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Tim Finan __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Mark Nichter __________________________________________________ Date: ______________ Michael Bonine Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Download Article

Religion, Identity and Citizenship The Predicament of Shia Fundamentalism in Bahrain Abdullah A. Yateem In 2011, Bahrain witnessed an unprecedented wave of political protests that came within a chain of protest movements in other Arab coun- tries, which later came to be known as the “Arab Spring.” Irrespective of the difference in the appellations given to these protests, their oc- currence in Bahrain in particular poses a number of questions, some of which touch upon the social and political roots of this movement, especially that they started in Bahrain, a Gulf state that has witnessed numerous political reformation movements and democratic transfor- mations that have enhanced the country’s social and cultural openness in public and political life. Despite this pro-democratic environment, the political movement rooted in Shi’a origins persisted in developing various forms of political extremism and violence, raising concerns among Sunni and other communities. This work evaluates the origins of Shi’a extremism in Bahrain. Keywords: Middle East, Bahrain, Shi’a fundamentalism, Islam, Arab Spring, violence, Iran In the course of the year 2011, Bahrain witnessed an unprecedented wave of political protests,1 and that came within a chain of protest movements in other Arab countries, which later came to be known as the “Arab Spring”. The names that have been, and are still being, given Scan this article to the Bahrain protests were widely varied: “revolution,” “terror,” “up- onto your rising,” “ordeal,” “protests,” “crisis,” depending on the -

Secondary School Effectiveness: an Empirical Study in the Country of Bahrain

Secondary school effectiveness: An empirical study in the country of Bahrain By Tahani Hasan Ali Maki A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Brunel Business School Brunel University London August 2017 Abstract Bahrain is a developed country that faces different economic and political challenges. Economically, Bahrain depends mostly on oil. However, there are some attempts to diversify its economy. Bahrain has established several economic projects to boost its economy including Bahrainization (Nationalization), Tamkeen (Labour fund), the Bahrain Business Incubator center, the banking sector, transport and communication, manufacturing and education. The Ministry of Education has established various educational projects to accommodate Bahrain Vision 2030, which aims to diversify the economy of Bahrain, building strategies of government and encouragement of a partnership between the private and public sector and the provision of an effective education system based on well trained teachers, enhancing the performance of public schools, provision of equal education opportunities for all students and improving and encouraging scientific education. This study investigates the different measures of secondary school effectiveness in Bahrain as a result of the new development of the education system in Bahrain including both teaching and improvement programs. These were initiated by the Ministry of Education in Bahrain and educational specialists. The literature reviews showed that secondary school effectiveness has been examined using specific factors – students’ performance, teachers’ performance, leadership. However, other factors such as leader-member exchange, value congruence, supportive supervisor communication and task performance have not been investigated well in the education sector and at the secondary school level in particular. The aim of this research is to investigate the impact of leader-member exchange, value congruence, supportive supervisor communication and task performance on secondary school effectiveness in Bahrain. -

Offshore Wind Energy Potential for Bahrain Via Multi-Criteria Evaluation

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 18 December 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202012.0474.v1 Research Article Offshore Wind Energy Potential for Bahrain via Multi-criteria Evaluation Mohamed Elgabiri 1, Diane Palmer 1,*, Hanan Al Buflasa 2 and Murray Thomson 1 1 Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK; [email protected] 2 University of Bahrain, Kingdom of Bahrain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44 1509 635604. ORCID 0000-0002-5381-0504 Abstract: Current global commitments to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases encourage national targets for renewable generation. Due to its small land mass, offshore wind could help Bahrain to fulfill its obligations. However, no scoping study has yet been carried out. The methodology presented here addresses this research need. It employs Analytical Hierarchy Process and pairwise comparison methods in a Geographical Information Systems environment. Publicly available land use, infrastructure and transport data are used to exclude areas unsuitable for development due to physical and safety constraints. Meteorological and oceanic opportunities are ranked, then competing uses are analyzed to deliver optimal sites for wind farms. The potential annual wind energy yield is calculated by dividing the sum of optimal areas by a suitable turbine footprint, to deliver maximum turbine number. Ten favourable wind farm areas were identified in Bahrain’s territorial waters, representing about 4% of the total maritime area, and capable of supplying 2.68 TWh/yr of wind energy or almost 10% of the Kingdom’s annual electricity consumption. Detailed maps of potential sites for offshore wind construction are provided in the paper, giving an initial plan for installation in these locations. -

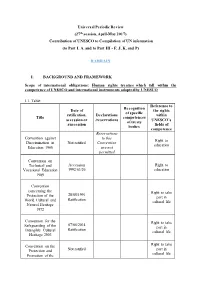

Universal Periodic Review (27Th Session, April-May 2017) Contribution of UNESCO to Compilation of UN Information (To Part I

Universal Periodic Review (27th session, April-May 2017) Contribution of UNESCO to Compilation of UN information (to Part I. A. and to Part III - F, J, K, and P) BAHRAIN I. BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORK Scope of international obligations: Human rights treaties which fall within the competence of UNESCO and international instruments adopted by UNESCO I.1. Table: Reference to Recognition Date of the rights of specific ratification, Declarations within Title competences accession or /reservations UNESCO’s of treaty succession fields of bodies competence Reservations Convention against to this Right to Discrimination in Not ratified Convention education Education 1960 are not permitted Convention on Accession Right to Technical and Vocational Education 1992/03/26 education 1989 Convention concerning the Right to take 28/05/1991 Protection of the part in Ratification World Cultural and cultural life Natural Heritage 1972 Convention for the Right to take 07/06/2014 Safeguarding of the part in Ratification Intangible Cultural cultural life Heritage 2003 Convention on the Right to take Protection and Not ratified part in cultural life Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions 2005 II. Input to Part III. Implementation of international human rights obligations, taking into account applicable international humanitarian law to items F, J, K, and P Right to education 1. NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK 1.1. Constitutional Framework 1. The Constitution (adopted on 14 February 2002)1 stipulates in its Article 7 that: (a) the State […] guarantees educational and cultural services to its citizens. Education is compulsory and free in the early stages as specified and provided by law. The necessary plan to combat illiteracy is laid down by law. -

The Development of Education National Report

The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) KINGDOM OF BAHRAIN MINISTRY OF EDUCATION THE DEVELOPMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL REPORT OF THE KINGDOM OF BAHRIAN (INCLUSIVE EDUCATION: THE WAY OF THE FUTURE) Presented to the Forty-Eight Session of the International Conference on Education (ICE) Geneva, 25-28 November 2008 Bahrain 2008 1 The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) 2 The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) H. H. Sheikh Khalifa H.M King Hamad Bin H.H Sheikh Salman Bin Bin Salman Al Khalifa Isa Al Khalifa Hamad Al Khalifa The Prime Minister The King of the The Crown prince Kingdom Deputy Supreme Commander of the BDF 3 The Development of Education: National Report of the Kingdom of Bahrain (Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future) Report Team Work General Supervision and Edited By: Faeqa Saeed AlSaleh Asst. Under-Secretary for Planning and Information Team Work Ali Salman Zuhair Acting, Head of Handicapped and Talented Section-Directorate of Special Education Amina Abdulla Kamal Acting, Head of Learning Difficulties Section-Directorate of Special Education Layla Ali AlMulla Head of Compulsory Education Unit-General and Technical Education Sector Suliman Mahmood Suliman Head of Financial Auditing-Directorate of Financial Resources Khaled Mohammed AlJawder Acting, head of Educational Planning-Directorate of Educational -

49Th BAHRAIN NATIONAL DAY

An EngineEngine for for economic growtheconomic growth At Tamkeen, we not only encourage Businesses and Bahraini individuals but empower them through diversified solutions which directly lead to economic development. Our primary objectives are to foster the development and growth of enterprises, and provide support to enhance the productivity and training of the national workforce. 2 Bahrain National Day 2020 cover4 pages.indd 4 12/15/20 11:17 AM An EngineEngine for for economic growtheconomic growth 75 Years of At Tamkeen, we not only encourage Businesses and Bahraini individuals but empower them through Luxury diversified solutions which directly lead to economic development. Our primary objectives are to foster the development and growth of enterprises, and provide support to enhance the productivity and training he largest Rolex Boutique in the of the national workforce. Middle East, the Modern Art Studio and Rolex boutique was meticulously over 30 years. In addition to being the largest Art Studio at the time, Heiniger proclaimed designed to embrace Arabian heritage one in the Middle East, it is also one of the it “one of the best Rolex shops in the while maintaining the exclusivity largest Rolex boutiques in the world. world.” One of its notable showcases was synonymous with the Swiss watchmaker, serving The story of Modern Art Studio dates back a display of the exclusive watches cleverly T arranged into individual letters to spell the its discerning clientele from its accessible location to 1936, when its founder Naji Murad had his in City Centre Bahrain. original shop in Government Avenue, Manama. name ROLEX. Today, Modern Art Studio The boutique, which features an exclusive VIP By 1940, history was made when the founder maintains its legacy as a family business suite for private viewings, offers a one-of-a-kind of Rolex Geneva, Hans Wilsdorf, officially as it continues to operate under the wise experience for visitors. -

Media Implications in Bahrain's Textbooks in Light of UNESCO's

Journal of Social Studies Education Research Sosyal Bilgiler Eğitimi Araştırmaları Dergisi 2017:8 (3), 259-281 www.jsser.org Media Implications in Bahrain’s Textbooks in Light of UNESCO's Media Literacy Principles Fawaz Alshorooqi1 & Saleh Moh'd Rawadieh2 Abstract This study aims to identify the media implications of textbooks in the Kingdom of Bahrain in light of the principles of media literacy emanating from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The study is based on the textbooks of Arabic Language and Education for Citizenship for the sixth primary, third intermediate and third secondary schools in the Kingdom of Bahrain for the academic year 2015/2016. The two researchers chose the descriptive and analytical approach to identify the media implications included in the selected textbooks. While conducting their study, the two researchers analyzed the implications of these textbooks based on the principles of media literacy stemming from UNESCO and its three fields, namely: knowledge and understanding of the media implications, assessment of media implications, and creation and use of media implications. The study revealed that these textbooks contained 168 media implications, with many of them concentrated in the field of knowledge and understanding of media implications. Assessment of media implications, and its creation and use came second and third, respectively. In fact, the study particularly revealed that the implications relating to the knowledge of the role of the media in democratic societies and the content of assessing the development of media implications are the most prevalent in the various analyzed school textbooks. This significant finding is highly important from a curricular perspective. -

BH11 Contents:Layout 1

THE REPORT Bahrain 2011 ECONOMY ENERGY INDUSTRY BANKING TOURISM CAPITAL MARKETS INSURANCE REAL ESTATE CONSTRUCTION TRANSPORT TELECOMS & IT INTERVIEWS 9 7 8 1 9 0 7 0 6 5 3 9 2 CONTENTS BAHRAIN 2011 43 Careful oversight: The Central Bank of Bahrain ISBN 978-1-907065-39-2 45 Roundtable: Adel El Labban, Group CEO & Editor-in-Chief: Andrew Jeffreys Managing Director, Ahli United Bank; Editorial Director: Peter Grimsditch Abdulkarim Ahmed Bucheery, CE, BBK; Regional Editor: Oliver Cornock Jamal Ali Al Hazeem, CEO, BMI Bank; and Editorial Manager: Gregory Kramer Abdul Razak Hassan Al Qassim, CEO, National Chief Sub-editor: Alistair Taylor Bank of Bahrain Deputy Chief Sub-editor: Jennie 49 Standard practice: The regulator is in the Patterson Sub-editors: Sam Inglis, Sean Cox, process of implementing Basel III Elyse Franko, Esther Parker 51 Managing the recovery: A measured response Contributing Sub-editors: Miia Bogdanoff, Barbara Isenberg has mitigated the effects of the downturn 53 A fresh approach: Local banks are increasingly Analysts: Nick Anderman, Ben Campbell, Marc Hoffman implementing new strategies Editorial Research Manager: Susan A solid base Mano€lu CAPITAL MARKETS Editorial Researchers: Matt Ghazarian, Page 16 57 Trading up: A new exchange and solid Souhir Mzali fundamentals are expected to contribute to Art Director: Yonca Ergin In recent years Bahrain has increasingly focused future growth Art Editors: Cemre Strugo, Meltem Muzmuz on efforts to diversify its economy, reducing its 61 Interview: Fouad Rashid, Director, Bahrain Illustrations: Shi-Ji Liang dependence on the extraction of its limited Bourse Photography: Jonathan Lewis hydrocarbons resources and turning to a mod- 62 Interview: Arshad Khan, Managing Director and Photo Editor: Mark Hammami el based primarily on services and manufactur- CEO, Bahrain Financial Exchange Production Manager: Selin Bolu ing. -

Bahreyn Insan Hakları Raporu 2013

BAHREYN İNSAN HAKLARI RAPORU 2013 Hazırlayanlar: Abdurrahman Babacan MAZLUMDER Dış İlişkiler Koordinatörü Üzeyir YİĞİT MAZLUMDER Ankara Şube YK Üyesi Mehmet TAHİROĞLU MAZLUMDER Antakya Şubesi Üyesi MAZLUMDER Genel Merkez Mithat Paşa Caddesi No: 62/4 Kızılay/ANKARA Tel: +90 (312) 418 10 46 - Faks: +90 (312) 418 70 93 http://mazlumder.org/ - E-Posta: [email protected] KISALTMALAR BAE: Birleşik Arap Emirlikleri KİK: Körfez İşbirliği Konseyi BBSK: Bahreyn Bağımsız Soruşturma Komisyonu DGDH: Deniz Gücü Destek Hareketi BSG: Bahreyn Savunma Gücü YYK: Yüksek Yargı Konseyi GSYH: Gayri Safi Yurtiçi Hasıla UET: Ulusal Eylem Tüzüğü SH: Selmaniye Hastanesi UBK: Ulusal Birlik Komitesi BİHM: Bahreyn İnsan Hakları Merkezi BSGF: Bahreyn Sendikalar Genel Federasyonu BÖB: Bahreyn Öğretmenler Birliği KHB: Kamu Hizmet Bürosu BTO: Bahreyn Ticaret Odası İÇİNDEKİLER KISALTMALAR 2 TAKDİM 4 I. GİRİŞ 7 II. GENEL ÇERÇEVE VE TARİHSEL ARKAPLAN 9 a) Siyasal Yapı 10 b) Siyasî Hareketlilik 11 c) İktisadî Yapı 13 d) Kimlik Yapısı 15 III. SÜREÇ VE ANALİZİ 18 a) Şubat - Mart 2011’de Yaşananlar 18 b) Gelinen Durum ve Temel İnsan Hakları İhlâlleri 32 IV. GENEL DEĞERLENDİRME VE SONUÇ 41 TAKDİM 2010 yılının Aralık ayında Tunus ile başlayan siyasi ve toplumsal hareketlilik, Kuzey Afrika ve Orta Doğu’ya değişim rüzgârlarını taşımış; önce Tunus, ardından Mısır ve Libya’da yıllardır devam eden otoriter rejimlerin birbiri ardına devrilmesiyle, coğrafyaya halkların meşru taleplerine dönük bir perspektifle bakılmaya başlanmıştır. Bu çerçevede, yine Mart 2011’de Suriye’de de benzer bir süreç başlamış; lakin halkın meşru ve temel talepleri, mevcut rejimce müzakere edilmek yerine kanlı ve insanlık dışı bir yöntemle bastırılmaya çalışılmış, ve dışsal etkilerin de devreye girmesiyle bugün de halen devam etmekte olan bir şiddet ortamına dönüşmüştür. -

Documents on Education Development

DocumentsDocuments onon EducatioEducationn DevelopmentDevelopment AfricaAfrica,, MiddlMiddlee East,East, AsiaAsia,, Pacific,Pacific, thethe Americas,Americas, EuropeEurope IDC PUBLISHER SS IDCIDC PublishersPublishers offersoffers a broadbroad rangerange ofof editionseditions foforr ththee disciplinesdisciplines ooff EconomicsEconomics,, StatisticsStatistics andand SocialSocial Sciences.Sciences. FilmedFilmed inin closeclose cooperationcooperation withwith thethe Joint Bank FundFund LibraryLibrary inin WashingtonWashington DC,DC, thesethese editionseditions makemake availableavailable seriesseries ofof officialofficial statistics,statistics, planninplanningg documentsdocuments,, anandd progressprogress reports.reports. InIn manymany cases,cases, IDIDCC PublisherPublisherss offerofferss remarkablremarkablee runrunss ooff thesthesee datadata,, spanninspanningg severaseverall decadedecadess ofof social-economicsocial-economic planningplanning anandd performance.performance. ContentsContents HowHow toto orderorder Africa .....................................................................................................1.1 MiddlMiddlee EasEastt / NortNorthh AfricAfricaa .................................................................1010 PleasePlease sensendd youyourr ordeorderr to the followinfollowingg address:address: EasEastt AsiaAsia ............................................................................................. I1 1l IDIDCC PublisherPublisherss SoutSouthh AsiaAsia ..........................................................................................1313 -

Dr. Mike Diboll: Reflections on My Practice in Bahrain

Reflexive Education, Revolution, and Counter-Revolution: Reflections on my experiences in Bahrain Dr Mike Diboll This reflection arises out of my experience working in education reform in Bahrain during the politically fraught years between 2007 and 2011, and is informed by the concept of ‘reflective practice’ pioneered during the 1970s by MIT educationalist Donald A. Schön, and described in his influential 1983 book The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Since Schön, Education development can been seen as partaking in a new, ‘reflexive’, or ‘second’ modernity, towards which the post-colonial polities of the Arab world are transitioning. Thus, the tensions between the ‘classic institutions’ of the region’s ‘first’ modernity,1 post-colonial states and the expectations of the younger generations whose subjectivities have in part been shaped by ‘reflexive modernity’ change-drivers, ‘super-modernizing forces’, forms part context of the current political contestations on-going in the Arab world since 2011. Similarly, education partakes in the co-construction and mediation of new identities and new forms of political consciousness in ways that were not predicted by the ruling regimes. This leads to the displacement of the post-colonial state’s ‘determinate rules’ as increasingly autonomous citizens assuming the role of ‘rule-seekers’ exercising ‘reflective judgement.’2 I had worked in higher education in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region since 2002. My first degree had been in Arabic, and prior to my work in the GCC, I had worked in Cairo, and travelled extensively in the region. I worked at the College of Arts, University of Bahrain (UoB), 2007-8, and was involved in the start-up of Bahrain Teachers’ College (BTC).