1 Chinese Online BBS Sphere: What BBS Has Brought to China By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

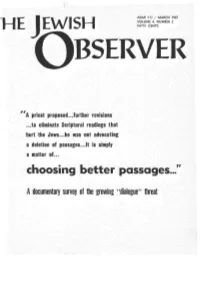

Choosing Better Passages:~."· ?

F' -~ . .. ·· . ( . · .-· · .. .•. ; .· .· , - . ; ·· · . .. .·· ...... ... ··" . .. .. ..· _.. ... - •· .-.· ... ..··· ;· ..· . : .··. ... · . .. ,. .. -· ....H .· , 'E --·_.:··.: . :E.. .·· w·· ··:·_· ._:·:"·1· ·s ··-.H. ·· .._._. · · :_-.·:-. _. ·. ". -. : .: ~~~J~''/ :U~~~~ - ~967 -·::-:.:< ·· · ~- . ·, .. -' .. · FIFTY CENTS · . · · ·- . .. .· . .. ·•· . ... .· .. .. ..· .·.·· .. , .. .. -. .. .·· .· .. ... .- . .. ' . .... ·' . , · . .. - . .. .. .. .. ·" - . -- . .•· . , - . ,, . - ·.... -. - . - .. · · -_-: :. ·.· ">- - -.··.--. : ·" A priest proposed·..• further revisions . : .· · . · · .> . ·~- :: -._ _..··· .-. -->. .. : . · . .. ..· ...- · .· .. · :": .. ~to eliminate Scriptural readings that · _. _ . ...: . ~- . ·: :· . · - . .. hurt the Jews ... he was not advocating . -· .. -· .· .... .·· ..· . .· ·· . " .. · . a deletion of passages.~ .It is simply : _ . _ . ... .. .· .-·· ·· .... -· ... a matter of ... choosing better passages:~." · ?: . ,. .: . -· - ·· ' . .. .· --.. Adocumentary survey of the growing "dialogue" threat -: .- ~ .- ... -·· -.~-~ ·· ~.- .··:.. ·. ... / . · - .. · ·- .· . .. .· _· .· ._ ... : .- ..... ..: . .. · - . ... .. ... · . .. .. .. · :: . - - . .· .. ' . ' - . ~ . ... .. -· .. .: . ·· _,. .. .. - ..· ..· ·· ,· . .. .. .... ~- . - - .. _,. : _.. _.· ·.. ...- .... ..'. .· .. -· -- .· . · ... .· .· · THE JEWISH QBSERVER In this issue ... "CHOOSING BETTER PASSAGES'' ..• A documentary survey of the growing "dialogue" threat. We believe that this survey should be read by thinking Jews far beyond the circle -

Internet and Freedom of Expression

EUROPEAN MASTER DEGREE IN HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATISATION 2000-2001 RAOUL WALLENBERG INSTITUTE Internet and Freedom of expression Rikke Frank Jørgensen© [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. Gregor Noll Abstract Internet challenges the right to freedom of expression. On the one hand, Internet empowers freedom of expression by providing individuals with new means of expressions. On the other hand, the free flow of information has raised the call for content regulation, not least to restrict minors’ access to potentially harmful information. This schism has led to legal attempts to regulate content and to new self- regulatory schemes implemented by private parties. The attempts to regulate content raise the question of how to define Internet in terms of “public sphere” and accordingly protect online rights of expression. The dissertation will argue that Internet has strong public sphere elements, and should receive the same level of protection, which has been given to rights of expression in the physical world. Regarding the tendency towards self- regulation, the dissertation will point to the problem of having private parties manage a public sphere, hence regulate according to commercial codes of consumer demand rather than the principles inherent in the rights of expressions, such as the right of every minority to voice her opinion. The dissertation will conclude, that the time has come for states to take on their responsibility and strengthen the protection of freedom of expression on Internet. 29.600 words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. Point of departure .................................................................................................. 4 1.2. Aim of dissertation................................................................................................. 6 2. System, lifeworld and Internet......................................................................................... -

Alark Joshi Dept

Alark Joshi Dept. of Diagnostic Radiology, Yale University Voice: (203) 737-5995 300 Cedar Street, TAC N138 E-mail: [email protected] New Haven, CT 06511 Website: www.cs.umbc.edu/˜alark1/ August 12th, 2008 RESEARCH INTERESTS Computer Graphics and Visualization. Primary interests and areas of expertise include volume visualiza- tion, non-photorealistic rendering and time-varying data visualization. EDUCATION February 2008 - Present Postdoctoral Associate. Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Yale University. “Novel visualization techniques for neurosurgical planning and stereotactic navigation” Advisor: Dr. Xenophon Papademetris. November 2007 Ph.D. Computer Science. University of Maryland Baltimore County. “Art-inspired techniques for visualizing time-varying data” Advisor: Dr. Penny Rheingans. December 2003 M. S. Computer Science. State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Innovative painterly rendering techniques using graphics hardware” Advisor: Dr. Klaus Mueller. July 2001 M.S. Computer Science. University of Minnesota Duluth. “Interactive Visualization of Models of Hyperbolic Geometry” Advisor: Dr. Douglas Dunham. June 1999 B.E. Engineering/Computer Science, University of Pune, India. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 02/08 - Present Postdoctoral Associate Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Yale University - Working on identifying visualization techniques for visualizing vascular data. - Developing novel interaction techniques for neurosurgical planning and navigation. - Developing visualization and software tools for BioImage Suite, an open -

Art-Inspired Techniques for Visualizing Time-Varying Data, Alark Joshi

APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: Art-inspired techniques for visualizing time-varying data Name of Candidate: Alark Joshi Ph.D. in Computer Science, 2007 Thesis and Abstract Approved: Dr. Penny Rheingans Associate Professor Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering Date Approved: Alark Joshi UniversityofMaryland,BaltimoreCounty Voice:(410)455-6339 Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering Fax: (410) 455-3969 1000 Hilltop Circle E-mail: [email protected] Baltimore,MD21250 Website:http://www.cs.umbc.edu/˜alark1/ RESEARCH INTERESTS Computer Graphics and Visualization. Primary interests and areas of expertise include volume visualization, non-photorealistic rendering and time-varying dataset visualization. EDUCATION Jan 2004 - Present Ph.D. student. University of Maryland Baltimore County. “Effective visualization of time-varying data using art-inspired principles” Advisor: Dr. Penny Rheingans. December 2003 M.S. Computer Science. State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Innovative painterly rendering techniques using graphics hardware” Advisor: Dr. Klaus Mueller. July2001 M.S.ComputerScience. UniversityofMinnesotaDuluth. “Interactive Visualization of Models of Hyperbolic Geometry” Advisor: Dr. Douglas Dunham. June1999 B.E.Engineering/ComputerScience,Universityof Pune, India. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY January 2004-Present Graduate Research Assistant Dept. of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering, University of Maryland, Baltimore County - Working on identifying and implementing non-photorealistic techniques for visu- alizing time-varying datasets. - Developed illustration-inspired techniques for visualizing computational fluid dy- namics time-varying data. - Worked in collaboration with Dr. Lynn Sparling in the Physics department at UMBC to develop visualization tools for conducting research in the field of hurri- cane visualization. - Developed art-inspired techniques to visualize global temperature trends in time- varying data January - May 2005 Instructor Dept. -

Received VERNER' Liipferf BERNHARD' Mcpherson ~ HAND Jul 25 2000 ICHARTEREDI .-W.~L~;Il~ 901- 15M STREET, N.W

-'\'h~INAL ......:j I """ RECEiVED VERNER' LIIPFERf BERNHARD' McPHERSON ~ HAND JUl 25 2000 ICHARTEREDI .-w.~l~;il~ 901- 15m STREET, N.W. tI'IQllf "lliE seal.'TM't WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-2301 (202) 371-6000 FAX: (202) 371-6279 EX PARTE OR LATE FILED WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL (202) 371-6206 July 25, 2000 VIA HAND DELIVERY Ms. Magalie Roman Salas Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, SW Washington, D.C. 20554 Re: Ex Parte ofThe Walt Disney Company in CS Docket No. ..., 00-30», Dear Ms. Salas: Enclosed for filing please find the original and one (1) copy ofthe ex parte filed on behalf ofThe Walt Disney Company in the above-referenced docket. Please stamp and return to this office with the courier the enclosed extra copy ofthis filing designated for that purpose. Please direct any questions that you may have to the undersigned. Enclosures cc: Chairman William, E. Kennard Commissioner Harold Furchtgott-Roth Commissioner Susan Ness Commissioner Michael Powell ~o. oi Copies rec'd Of1 Commissioner Gloria Tristani List ABe 0 E • WASHINGTON. DC • HOUSTON • AUSTIN • HONOLULU • LAS VEGAS • McLEAN • MIAMI Deborah Lathan Bill Johson James Bird Royce Dickens Linda Senecal Darryl Cooper George Vradenberg, III Jill A. Lesser Steven N. Teplitz Richard E. Wiley Timothy Boggs Catherine R. Nolan Aaron I. Fleischman Arthur H. Harding Craig A. Gilley •..;;,'~C'E'\f lCr,-o '" '. 2::; 2000 Before the Federal Communications Commission !'~'-.I'~ oorAllll. Washington, D.C. 20554 &rl"P.,;: iJii ,HE SECAETMr In the Matter of ) ) Applications ofAmerica Online, Inc. ) CS Docket No. 00-30 and Time Warner, Inc. -

Majority Backs Medical Marijuana, but Feds Won't Budge

Advertisement MAIL Search News and Topics Front Page Team Nation World Politics Opinion Weird News More Send Us Feedback MONEY IN POLITICS MEMO TO OBAMA FIRST PERSON BIBLICAL WEAPONS Justices Gut Opinion: Mr. Photos: Back in Haiti, Petraeus Tries to Quell 'Jesus' Gun Campaign-Finance President, Govern as Searching for Friends Questions Restrictions You Promised NATION Majority Backs Medical Marijuana, but Advertisement Feds Won't Budge Updated: 1 day 1 hour ago Print Text Size E-mail More (Jan. 20) -- When it comes to reforming the nation's health care system, Americans are firmly divided. But a surprisingly large majority now agrees that if you're sick, you should be allowed to pass the peace pipe. Eighty-one percent of U.S. adults favor legalizing marijuana in a medical Carl Franzen context, according to a telephone poll conducted by ABC News and the Contributor Washington Post last week. In 1997, 69 percent of respondents were in favor TOP NEWS of the idea. Sphere AP Real-Time Web The news led some, such as the Raw Story's Stephen C. Webster, to conclude that "the medical Justices Gut Campaign-Finance Restrictions marijuana debate among American voters is over." Indeed, voters in nine states have approved Petraeus Tries to Quell 'Jesus' Gun Questions medical marijuana provisions, beginning with California in 1996. Immigrants Have Complex View of Race, Survey Finds Air France Frets Over How to Seat the Obese But it's not just citizens who are catching whiffs of a budding new era: The legislatures of five other Betty Broderick, Symbol of Bitter Divorce, Seeks states, most recently New Jersey, also passed their own laws setting up specific, government- Parole sponsored programs that provide controlled access to the plant to ill patients -- bringing to 14 the Scots May Be Allowed to Get Help in Ending Their Lives grand total of states where medical marijuana is available. -

The Vignette in 21St-Century American Fiction a Dissertation

Glimpses of the World: The Vignette in 21st-Century American Fiction A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of English Caren Irr, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Daniella Gáti May 2021 The signed version of this form is on file in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. This dissertation, directed and approved by Daniella Gáti’s Committee, has been accepted and approved by the Faculty of Brandeis University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Eric Chasalow, Dean Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dissertation Committee: Caren Irr, English Ulka Anjaria, English Jessica Pressman, English and Comparative Literature, San Diego State University Copyright by Daniella Gáti 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to everyone who contributed their unwavering support and who were always on my side, whether in person or in thought, as I moved ever closer to the finish line. This has been the work of years, and like all dissertations, it is incomplete. Even so, it would never have reached this state without the help of my advisors, my academic friends and mentors both official and unofficial, my invaluable writing buddy, with whom we shared the joys and pains of finishing our respective dissertations, and the various academic communities in which I have had the fortune to exchange and discuss ideas. Thank you for all those innumerable hours of shared thinking and writing. Special thanks go to the curators and staff at the Huntington Library, where I was able to engage with wonderful archival material without which this work would not have been possible.