JPA21 Crimble Mill Historic Environment Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

03Cii Appx a Salford Crescent Development Framework.Pdf

October 2020 THE CRESCENT SALFORD Draft Development Framework October 2020 1 Fire Station Square and A6 Crescent Cross-Section Visual Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 Contents 01 Introduction 8 Partners 02 Salford’s Time 24 03 The Vision 40 04 The Crescent: Contextual Analysis 52 05 Development Framework Area: Development Principles 76 06 Character Areas: Development Principles 134 07 Illustrative Masterplan 178 08 Delivering The Vision: Implementation & Phasing 182 Project Team APPENDICES Appendix A Planning Policy Appendix B Regeneration Context Appendix C Strategic Options 4 5 Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 Salford Crescent Visual - Aerial 6 7 Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 01. Introduction 8 9 Draft Crescent Development Framework October 2020 01. Introduction In recent years, Salford has seen a substantial and contributes significantly to Salford’s economy, The next 20 years are going to be very amount of investment in new homes, businesses, but is currently divided by natural and man-made infrastructure and the public realm. The delivery infrastructure including the River Irwell, railway line important for Salford; substantial progress has of major projects such as MediaCityUK, Salford and the A6/Crescent. This has led to parts of the been made in securing the city’s regeneration Central, Greengate, Port Salford and the AJ Bell Framework Area being left vacant or under-utilised. Stadium, and the revitalisation of road and riverside The expansion of the City Centre provides a unique with the city attracting continued investment corridors, has transformed large areas of Salford opportunity to build on the areas existing assets and had a significant impact on the city’s economy including strong transport connections, heritage from all over the world. -

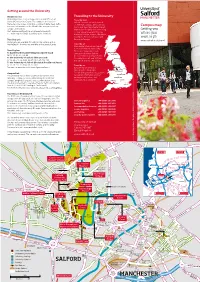

University of Salford (The Crescent) Piccadilly

Getting around the University Disabled access Travelling to the University All buildings have level or ramped access and lifts except Travel by train Horlock/Constantine Courts. The campus is not level, so Salford Crescent station is located there are some slopes, including a couple of quite steep paths. on Peel Park campus. Direct services Campus map For more information on the DisabledGo assessment of our run to and from Manchester Airport, campus and facilities. Manchester Piccadilly (for connecting Getting you Visit: www.equality.salford.ac.uk/page/accessibility to Inter city services) and Victoria, where you See main map for disabled parking space locations. Blackpool, Bolton, Buxton, Blackburn, Southport, Preston, Lancaster and want to go Barrow-in-Furness. Travel by cycle www.salford.ac.uk/travel Cycle parks are available throughout the campus and at MediaCityUK. Showers are available at the Sports Centre. Travel by air Manchester International Airport is 15 miles from the University. Travel by bus There are regular direct train To Castle Irwell Student Village (Cromwell Road) GLASGOW services to and from Salford EDINBURGH M10, 10, 27, 51, 52, 93 Crescent station and Manchester To the University of Salford (The Crescent) Piccadilly. Buses 43 and 105 link NEWCASTLE 8, 12, 26, 31, 32, X34, 36, 37, X61, 67, 50, 100 the airport and the city centre. To the University of Salford (Frederick Road/Broad Street) 8, 12, 26, 31, 32, X34, 36, 37, X61 Travel by car For more information visit: www.tfgm.com/buses Car parking on campus is SALFORD LEEDS LIVERPOOL limited and is chargeable. -

4 Port Salford Heritage Assessment All Sites

Salford City Council Revised Draft Salford Local Plan Heritage Assessments of Site Allocations February 2019 1 Contents Page number Introduction 3 Land west of Hayes Road 12 Charlestown Riverside 18 Brackley Golf Course 33 Land west of Kenyon Way 34 Orchard Street 35 Land south of the Church of St Augustine 48 Land north of Lumber Lane 64 Land at A J Bell Stadium 71 Hazelhurst Farm 80 Land east of Boothstown 81 Western Cadishead and Irlam 91 Extension to Port Salford 107 Appendix A – Historic England Response to the Draft Salford 124 Local Plan Consultation December 2016 Appendix B – Salford City Council Initial Screening Assessment and 136 GMAAS Archaeological Screening Assessment Introduction These background papers have been produced to form part of the evidence base for the local plan. The assessments have been based on the site allocations and boundaries as proposed in the Draft Local Plan (November 2016) and used to inform the development of the Revised Draft Local Plan and specifically, the site requirements included within the site allocation policies. Background The Draft Local Plan was published for consultation for a 10 week period commencing 8 November 2016 to 16 January 2017. In response to the Draft Local Plan consultation, representations were received from Historic England as a statutory consultee in relation, in part, to the supporting evidence base to the local plan. Historic England did not consider that the city council had adequately demonstrated that the policies and proposals contained within the Draft Local Plan had been informed by a proper assessment of the significance of the heritage assets in the area. -

Cotton Mills for the Continent

cotton mills_klartext.qxd 30.05.2005 9:11 Uhr Seite 1 Cotton mills for the continent Sidney Stott und der englische Spinnereibau in Münsterland und Twente Sidney Stott en de Engelse spinnerijen in Munsterland en Twente 1 cotton mills_klartext.qxd 30.05.2005 9:11 Uhr Seite 2 Cotton mills for the continent Bildnachweis/Verantwoording Sidney Stott und der englische Spinnereibau in afbeldingen Münsterland und Twente – Sidney Stott en de Engelse spinnerijen in Munsterland en Twente Andreas Oehlke, Rheine: 6, 47, 110, 138 Archiv Manz, Stuttgard: 130, 131, 132l Herausgegeben von/Uitgegeven door Axel Föhl, Rheinisches Amt für Denkmalpflege, Arnold Lassotta, Andreas Oehlke, Siebe Rossel, Brauweiler: 7, 8, 9 Axel Föhl und Manfred Hamm: Industriegeschichte Hermann Josef Stenkamp und Ronald Stenvert des Textils: 119 Westfälisches Industriemuseum, Beltman Architekten en Ingenieurs BV, Enschede: Dortmund 2005 111, 112, 127oben, 128 Fischer: Besteming Semarang: 23u, 25lo Redaktion/Redactie Duncan Gurr and Julian Hunt: The cotton mills of Oldham: 37, 81r Hermann Josef Stenkamp Eduard Westerhoff: 56, 57 Hans-Joachim Isecke, TECCON Ingenieurtechnik, Zugleich Begleitpublikation zur Ausstel- Stuhr: 86 lung/Tevens publicatie bij de tentoonstelling John A. Ledeboer: Spinnerij Oosterveld: 100 des Westfälischen Industriemuseums John Lang: Who was Sir Philip Stott?: 40 Museum Jannink, Enschede: 19, 98 – Textilmuseum Bocholt, Museum voor Industriële Acheologie en Textiel, des Museums Jannink in Enschede Gent: 16oben und des Textilmuseums Rheine Ortschronik (Stadtarchiv) Rüti: 110 Peter Heckhuis, Rheine: 67u, 137 Publikation und Ausstellung ermöglichten/ Privatbesitz: 15, 25u, 26u, 30, 31, 46, 65, 66, 67oben, 83oben, 87oben, 88u, 88r, 90, 92, 125l Publicatie en tentoonstelling werden Rheinisches Industriemuseum, Schauplatz Ratingen: mogelijk gemaakt door 11, 17 Europäische Union Ronald Stenvert: 26r, 39r, 97, 113oben, 113r, 114, 125r, Westfälisches Industriemuseum 126 Kulturforum Rheine Roger N. -

The Chapel Street Heritage Trail Queen Victoria, Free Parks, the Beano, Marxism, Heat, Vimto

the Chapel Street heritage trail Queen Victoria, free parks, the Beano, Marxism, Heat, Vimto... ...Oh! and a certain Mr Lowry A self-guided walk along Chapel Street There’s more to Salford than its favourite son and his matchstick men from Blackfriars Bridge to Peel Park. and matchstick cats and dogs. Introduction This walk takes in Chapel Street and the Crescent – the main corridor connecting Salford with Manchester city centre. From Blackfriars Bridge to Salford Museum and Art Gallery should take approximately one and a half hours, with the option of then exploring the gallery and Peel Park afterwards. The terrain is easy going along the road, suitable for wheelchair users and pushchairs. Thanks to all those involved in compiling this Chapel Street heritage trail: Dan Stribling Emma Foster Mike Leber Ann Monaghan Roy Bullock Tourism Marketing team www.industrialpowerhouse.co.uk If you’ve any suggestion for improvements to this walk or if you have any memories, stories or information about the area, then do let us know by emailing [email protected] www.visitsalford.com £1.50 Your journey starts here IN Salford The Trail Background Information Chapel Street was the first street in the United Kingdom to be lit by gas way back in 1806 and was one of the main roads in the country, making up part of the A6 from London to Glasgow. Today it is home to artists’ studios, Salford Museum and Art Gallery, The University of Salford, great pubs and an ever- increasing number of businesses and brand new residences, meaning this historic area has an equally bright future. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Planning and Transportation Regulatory Panel, 19/09/2019 11:45

Public Document Pack Planning and Transportation Regulatory Panel Dear Member, You are invited to attend the meeting of the Planning and Transportation Regulatory Panel to be held as follows for the transaction of the business indicated. Miranda Carruthers-Watt Proper Officer DATE: Thursday, 19 September 2019 TIME: 11.45 am VENUE: Salford Suite, Salford Civic Centre, Chorley Road, Swinton In accordance with ‘The Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014,’ the press and public have the right to film, video, photograph or record this meeting. Members attending this meeting with a personal interest in an item on the agenda must disclose the existence and nature of that interest and, if it is a prejudicial interest, withdraw from the meeting during the discussion and voting on the item. AGENDA 1 The Panel is asked to consider whether it agrees to the inclusion of the items listed in Parts 1 and 2 of the agenda. 2 Apologies for absence. 3 Declarations of interest. 4 To approve as a correct record the minutes of the meeting held (Pages 1 - 4) on 25 July 2019. 5 Planning applications and related development control issues. (Pages 5 - 10) 5a 19/73607/FUL 275 - 283 Chapel Street, Salford M3 5JZ (Pages 11 - 30) 5b 19/73543/REM Ashtonfields Site Part of British Coal Yard, (Pages 31 - 44) Ravenscraig Road, Little Hulton M38 9PU 6 Planning applications determined under delegated authority. (Pages 45 - 126) 7 Planning appeals. (Pages 127 - 132) 8 Urgent business. 9 Exclusion of the Public. 10 Part 2 - Closed to the Public. 11 Urgent business. -

The Manchester Investment Portfolio 曼彻斯特 投资组合

THE MANCHESTER INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO 曼彻斯特 投资组合 Manchester – China Forum is delighted to be able to present this document detailing the tremendous array of investment opportunities in Greater Manchester. The Forum is a business-led initiative aimed at increasing Greater Manchester’s commercial connectivity with China. The forum is led by the following companies: The Forum would like to thank Addleshaw Goddard and Deloitte for their kind support and advice with the production of the Investment Portfolio. This publication has been written in general terms and therefore cannot be relied on to cover Photography courtesy of: specific situations; application of the principles set out will depend upon the particular Becky Lane circumstances involved and it is recommended that you obtain professional advice before acting Rick Grange or refraining from acting on any of the contents of this publication. The Manchester-China Ben Page Forum, its Members and the Sponsors of this document accept no duty of care or liability for any TfGM loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any material in this publication. Deloitte refers to Deloitte LLP, the United Kingdom member firm of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (“DTTL”), a UK private company limited by guarantee, and its network of member firms, each of which is a legally separate and independent entity. Please see www.deloitte.co.uk/ about for a detailed description of the legal structure of DTTL and its member firms. © 2014 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Deloitte LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC303675 and its registered office at 2 New Street Square, London, EC4A 3BZ, United Kingdom. -

Campus and Regular Bus Services Stopping 11 Along the Crescent

C A Lowry Car Park VISIT US B 12 The University of Salford is situated just a mile and a Delaney Car Park half from Manchester city centre and we have excellent transport links, with Salford Crescent train station on campus and regular bus services stopping 11 along the Crescent. 18 Frederick Road Our campus at MediaCityUK is a mile and a half Car Park from our main campus and our students and sta PEEL PARK can get the number 50 bus between the main campus 13 and MediaCityUK for free. It runs regularly throughout the day. University Road 17 16 Belvedere Road 10 CAMPUS MAP KEY 15 Food and drink outlets 9 Car Park 14 Accommodation 7 A Peel Park Quarter Mary Seacole Car Park B John Lester Court Salford 8 C Eddie Colman Court Crescent Station Main University Buildings 6 1 Maxwell Building 2 Maxwell Hall 5 3 Gilbert Rooms 4 Peel Building MediaCityUK Broadway 5 Newton Building tram stop 6 Cockcroft Building Broadway 7 Lady Hale Building Salford The Meadow 8 New Adelphi Building 4 Museum 3 9 Cliord Whitworth Library 10 Chapman Building 11 University House 12 Sports Centre Crescent (A6) 2 1 13 Faith Centre 14 Mary Seacole Building BBC ITV 19 15 Brian Blatchford Building Studio10 16 Busy Bees Childrens Nursery R IV 17 Allerton Building 24 20 E R 18 MediaCityUK I Podiatry Clinic 21 R tram stop W E 19 Joule House BBC L L 20 Alumni House 21 The Old Fire Station BBC 22 Crescent House 23 Humphrey Booth House 22 24 University of Salford (MediaCityUK) 23 The Quays The Lowry The Lowry Outlet Mall Theatre Irwell Place Car Park. -

The Textile Mills of Lancashire the Legacy

ISBN 978-1 -907686-24-5 Edi ted By: Rachel Newman Design, Layout, and Formatting: Frtml Cover: Adam Parsons (Top) Tile wcnving shed of Queen Street Mill 0 11 tile day of Published by: its clo~urc, 22 September 2016 Oxford Ar.:haeology North, (© Anthony Pilli11g) Mill 3, Moor Lane Mills, MoorLnJ1e, (Bottom) Tile iconic, Grade Lancaster, /-listed, Queen Street Mill, LAllQD Jlnrlc S.lfke, lire last sun,ini11g example ~fan in fad steam Printed by: powered weaving mill with its Bell & Bain Ltd original loom s in the world 303, Burn field Road, (© Historic England) Thornlieba n k, Glasgow Back Cover: G46 7UQ Tlrt' Beer 1-ln/1 at Hoi till'S Mill, Cfitlwroe ~ Oxford Archaeolog)' Ltd The Textile Mills of Lancashire The Legacy Andy Phelps Richard Gregory Ian Miller Chris Wild Acknowledgements This booklet arises from the historical research and detailed surveys of individual mill complexes carried out by OA North during the Lancashire Textile Mills Survey in 2008-15, a strategic project commissioned and funded by English Heritage (now Historic England). The survey elicited the support of many people, especial thanks being expressed to members of the Project Steering Group, particularly Ian Heywood, for representing the Lancashire Conservation Officers, Ian Gibson (textile engineering historian), Anthony Pilling (textile engineering and architectural historian), Roger Holden (textile mill historian), and Ken Robinson (Historic England). Alison Plummer and Ken Moth are also acknowledged for invaluable contributions to Steering Group discussions. Particular thanks are offered to Darren Ratcliffe (Historic England), who fulfilled the role of Project Assurance Officer and provided considerable advice and guidance throughout the course of the project. -

H3/4 Western Cadishead and Irlam

Greater Manchester Spatial Framework and Salford Local Plan Archaeological Assessment: H3/4 Western Cadishead and Irlam Client: Salford City Council Desk based Assessment: Steve Tamburello © CfAA: Greater Manchester Spatial Framework and Salford Local Plan Archaeological Assessment : H3/4 Western Cadishead and Irlam 1 Site Location: The Site is located to the north-west of Cadishead and Irlam,and is bordered by the A580 to the north and Glaze Brook to the west. NGR: Centred on NGR SJ 71261 93997 Internal Ref: SA/2018/73 Prepared for: Salford City Council Document Title: Greater Manchester Spatial Framework and Salford Local Plan Archaeological Assessment: H3/4 Western Cadishead and Irlam Document Type: Desk-based Assessment Version: Version 1.3 Author: Steve Tamburello Position: Supervising Archaeologist Date: November 2018 Approved by: Ian Miller BA FSA Position: Assistant Director Date: November 2018 Signed: Copyright: Copyright for this document remains with the Centre for Applied Archaeology, University of Salford. Contact: Salford Archaeology, Centre for Applied Archaeology, Peel Building, University of Salford, Salford, M5 4WT Telephone: 0161 295 4467 Email: Disclaimer: This document has been prepared by Salford Archaeology within the Centre for Applied Archaeology, University of Salford, for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be used or relied upon for any other project without an independent check being undertaken to assess its suitability and the prior written consent and authority obtained from the Centre for Applied Archaeology. The University of Salford accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than those for which it was commissioned. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Planning and Transportation

Public Document Pack Planning and Transportation Regulatory Panel Dear Member, You are invited to attend the meeting of the Planning and Transportation Regulatory Panel to be held as follows for the transaction of the business indicated. Miranda Carruthers-Watt Proper Officer DATE: Thursday, 10 May 2018 TIME: 9.30 am VENUE: Salford Suite, Salford Civic Centre, Chorley Road, Swinton In accordance with ‘The Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014,’ the press and public have the right to film, video, photograph or record this meeting. Members attending this meeting with a personal interest in an item on the agenda must disclose the existence and nature of that interest and, if it is a prejudicial interest, withdraw from the meeting during the discussion and voting on the item. Please note that there will be a break for Members at approximately 11.15 a.m. until 11.30 a.m., and at 1.00 p.m. until 1.30 p.m. AGENDA 1 The Panel is asked to consider whether it agrees to the inclusion of the items listed in Parts 1 and 2 of the agenda. 2 Apologies for absence. 3 Declarations of interest. 4 To approve, as a correct record, the minutes of the meeting held (Pages 1 - 2) on 5th April 2018. 5 Planning applications and related development control issues. (Pages 3 - 10) 9:30 A.M. 5a 17/71158/FUL 352 Walkden Road, Worsley M28 7ER (Pages 11 - 28) 5b 18/71423/FUL Broadoak Primary School, Fairmount Road, Swinton (Pages 29 - 34) M27 0EP 5c 17/70056/FUL Land Formerly Griffin Hotel, Lower Broughton Road, (Pages 35 - 56) Salford 5d 18/71347/COU 6 and 8 Bindloss Avenue, Eccles M30 0DU (Pages 57 - 66) 5e 18/71548/HH 123 Worsley Road, Worsley M28 2WG (Pages 67 - 72) 11:30 A.M. -

Hit Ctrl+F to Search This Document Last Refreshed: 02/02/2018 at 08:01

REGISTERED FOOD PREMISES TIP: HIT CTRL+F TO SEARCH THIS DOCUMENT LAST REFRESHED: 02/02/2018 AT 14:01 ESTABLISHMENT ESTABLISHMENT NAME ADDRESS (CLICK TO VIEW ON A MAP) BUSINESS TYPE FOOD DATE OF DATE OF ID HYGIENE LAST NEXT RATING INSPECTION INSPECTION 2329 6 / CUT PIZZA CO. 247-251 MONTON ROAD ECCLES SALFORD M30 9PS RESTAURANT/ 5 12/06/2019 11/06/2021 CAFE/CANTEEN 2041 7 DAYS 62 LIVERPOOL ROAD ECCLES M30 0WA SMALL RETAILER 4 25/11/2019 24/11/2022 157347 AADAMS GRILL UNIT 2A 400 ORDSALL LANE SALFORD M5 3BU TAKE AWAY 3 15/12/2020 16/06/2022 7547 AAHIL CONVENIENCE 74 BARTON ROAD SWINTON M27 5LP SMALL RETAILER 4 02/05/2019 01/05/2021 STORE 2486 ABBEYDALE NURSING 11-12 THE POLYGON ECCLES M30 0DS CARING PREMISES 4 20/09/2019 19/09/2020 HOME 1369 ABBEYFIELD SOCIETY ABBEYFIELD HOUSE BRIDGEWATER ROAD WORSLEY CARING PREMISES 5 07/11/2019 06/11/2022 M28 3JE 2542 ABBEY GROVE ELDERLY ABBEY GROVE RESIDENTIAL HOME 2-4 ABBEY GROVE CARING PREMISES 5 02/09/2021 02/09/2022 PERSONS HM ECCLES SALFORD M30 9QN 2263 ABC EXTRA 202 LIVERPOOL ROAD IRLAM M44 6FE SMALL RETAILER 5 16/03/2021 15/03/2024 1186 ABC FOOD STORE 158 BOLTON ROAD WORSLEY M28 3BW SMALL RETAILER 1 14/12/2020 15/06/2022 21389 ABC MINI STORE LTD GROUND FLOOR 562 LIVERPOOL ROAD IRLAM SMALL RETAILER 5 31/01/2020 30/01/2023 SALFORD M44 6ZA 158776 ABC PRE-SCHOOL LTD WITHIN BOOTHSTOWN METHODIST PRIMARY SCHOOL CARING PREMISES 5 26/03/2019 24/09/2020 BOOTHSTOWN CHAPEL STREET WORSLEY SALFORD M28 1DG 164822 ABM'S LIONBREW CAFE WITHIN LOWER LODGE AGECROFT ROAD SWINTON RESTAURANT/ 3 25/06/2021 25/12/2022