Sunniva Abelli Masterarbete 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beethoven and Banjos - an Annual Musical Celebration for the UP

Beethoven and Banjos - An Annual Musical Celebration for the UP Beethoven and Banjos 2018 festival is bringing Nordic folk music and some very unique instruments to the Finnish American Heritage Center in Hancock, Michigan. Along with the musicians from Decoda (Carnegie Hall’s resident chamber group) we are presenting Norwegian Hardanger fiddler Guro Kvifte Nesheim and Swedish Nyckelharpist Anna Gustavsson. Guro Kvifte Nesheim grew up in Oslo, Norway, and started playing the Hardanger fiddle when she was seven years old. She has learned to play the traditional music of Norway from many great Hardanger fiddle players and has received prizes for her playing in national competitions for folk music. In 2013 she began her folk music education in Sweden at the Academy of Music and Drama in Gothenburg. Guro is composing a lot of music, and has a great interest and love for the old music traditions of Norway and Sweden. In 2011 she went to the world music camp Ethno and was bit by the “Ethno-bug”. Since then she has attended many Ethno Camps as a participant and leader, and setup Ethno Norway with a team of fellow musicians. In spring 2015 she worked at the Opera House of Gothenburg with the dance piece “Shadowland”. The Hardanger fiddle is a traditional instrument from Norway. It is called the Hardanger Fiddle because the oldest known Hardanger Fiddle, made in 1651, was found in the area Hardanger. The instrument has beautiful decorations, traditional rose painting, mother-of-pearl inlays and often a lion’s head. The main characteristic of the Hardanger Fiddle is the sympathetic strings that makes the sound very special – it’s like an old version of a speaker that amplifies the sound. -

1 Sotholms Och Svartlösa Härader

1 SOTHOLMS OCH SVARTLÖSA HÄRADER INNEHÅLL 2 SVARTLÖSA HÄRAD 26 ÖSMODRÄKTEN 3 PÅ BANAN 28 POLONESSEBOKEN 4 SPELMÄN 30 VEM ÄR SOM EJ... )0 DANSEN PÅ SÖDERTÖRN 32 SKIVSPALTEN 18 JAG MINNS 34 HARPOLEK 20 SÄGNER OCH MINNEN 36 SORUNDAVISAN 22 HANDLAREVISAN Omdagsbild: Byspelmannen, målad av den tyske 23 DRÄKTEN PÅ SÖDERTÖRN konstmren Hans Thoma, 1839- 1924. 24 SORUNDADRÄKTEN " '. .h %5z"f*:%:?Z? ' ""'= " " """' "É=..,, ~ "') L' . """ " ', ~j1K q' . , ,, ',. U · " "r"^ pgc. " ,\,\ b - h1· a»,' X' " am v""' ! °""'"'""" r, "=: " " - ' "::0 T' "": ±%v"4 '&" m ""' "' SY . ·:%, ·- -' ' " '" ·x"f;" '"3' " "L. .7yj|::c"^X+"m "" " ·P :k -'e ., ==9"2" ;6 ¢. ' "" , "t?:,:k ' ' "' 'l" ,'" " " W r' " QL"+:S\ja, " :" l V ,/i ,b ,, "¶%1 p -J' l" · t, · l. tk. "", ' n rtarNm. .,~ b- " 0 bm mb n g . · · K ' 0m· vf . V h~~m~' .·· 2?'' b « "brgib, 4 . .~,._+.:' " "" "".. cl Rm"m "' :__ T " " r ' . 0ybW +· M0~ f , 0m. : Q SÖRMLAN%LÅTEN dktribue ra8 till medlemmarna l Södermanland8 SpelmanMörbund och Sörmländska Ungdommngen. Utomstående kan prenumerera på Spelman8förbundet8 cirkulär (Inkl. SÖRMLANDS- LÄTEN) för ett år genom att 8åtta in kr IS: -- på postgiro 12 24 74 - O, adrem Södermanland8 Spelmam- förbund. Skriv "Cfrkulårprenumeration" på Ullongen! Upplaga: I. 750 ex Utkommer 2 gånger per år 2 GIOVANNA BASSI - PREMIÄRDANSÖS OCH SVARTLÖSA HÄRAD SÖRMLÄNDSK GODSÄGARINNA Marianne Strandberg Giovanna var dotter till den italienska hovstdhnästa- ren Stefano Bassi och hans franska hustru Angelique. Svartlösa hdrod har fött sitt namn efter tingsstCMet Hon föddes troligen 13 juni 1762 i Paris. Hon kom till SvartakSt (SvartalC$CSt) eller SvanlCSten (löt, Im troli- Sverige 1783 tilkammans med sin bror och omtalldes gen äng) där ting med Övm Tör (norra Södertöm) Nils som ballerina vid teatern samma år. -

Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using Folk Dance in Secondary Schools

Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using folk dance in secondary schools By Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Scourfield Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part The Full English The Full English was a unique nationwide project unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage by making over 58,000 original source documents from 12 major folk collectors available to the world via a ground-breaking nationwide digital archive and learning project. The project was led by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and in partnership with other cultural partners across England. The Full English digital archive (www.vwml.org) continues to provide access to thousands of records detailing traditional folk songs, music, dances, customs and traditions that were collected from across the country. Some of these are known widely, others have lain dormant in notebooks and files within archives for decades. The Full English learning programme worked across the country in 19 different schools including primary, secondary and special educational needs settings. It also worked with a range of cultural partners across England, organising community, family and adult learning events. Supported by the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Folk Music Fund and The Folklore Society. Produced by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), June 2014 Written by: Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield Edited by: Frances Watt Copyright © English Folk Dance and Song Society, Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield, 2014 Permission is granted to make copies of this material for non-commercial educational purposes. -

The Dissemination of the Nyckelharpa

The Dissemination of the Nyckelharpa The Ethnic and the non-Ethnic Ways Gunnar Ternhag & Mathias Boström, Dalarnas Forskningsråd, Falun, Sweden The Ethnic and the non-ethnic Many traditional instruments are strongly linked to ethnic concepts. These connotations are often well known to musicians and listeners both inside and outside ethnic communities, although they are valued and interpreted differently. Some instruments are regarded as typical of certain cultures; you could even call them emblematic. This is evident when it comes to national cultures. The Finnish kantele and the Norwegian hardanger fiddle are typical examples of this (cf. Torp 1998). Other instruments have ethnic connotations without being symbols for specific cultures. The djembe drum, for instance, is mostly considered as simply “African” in the Western world. These and many similar instruments are more or less accessible to everyone today. The same goes for music and playing styles. Record stores, festivals, workshops and the Internet can easily provide everyone interested with inspiring products. A musician who wants to pick up a traditional musical instrument from a different culture than his or her own has to choose. He or she may try to learn the original music and playing style associated with the instrument; the so-called “tradition.” We will call this the ethnic way of approaching the instrument. The beginner wants to learn the instrument and its music in the same way as if he or she were living in the original community of the instrument. In this way many musicians in Sweden and other similar countries have learned how to play high- land-pipes or bouzouki—and have become Scots or Greeks in their musicianship. -

At May 2013 Proof All.Pdf

2013 SEASON PREVIEW — PAGES 6–7 Q&A WITH HERSCHEND’S JOEL MANEY — PAGES 41–42 © TM Your Amusement Industry NEWS Leader! Vol. 17 • Issue 2 MAY 2013 Merlin Entertainments’ U.S. Legoland Hotel a brickwork bonanza Southern California leap into the destination cat- their perspective that has gone egory. into the planning first and park becomes Officially opened April foremost.” full-fledged resort 5 after several days of me- AT found this in abundant dia previews, the three-story, evidence during a visit to the STORY: Dean Lamanna Special to Amusement Today 250-room inn, like the park, brightly multicolored hotel is designed to immerse fami- — beginning with the giant, CARLSBAD, Calf. — With lies with children aged two stream-breathing green drag- its unique toy theme and se- to 12 in the creative world of on made from some 400,000 ries of tasteful, steadfastly Lego toys. Guests of the hotel, Lego bricks that welcomes kid-focused additions over which is located adjacent to lodgers while guarding the its 14-year history, including Legoland’s entrance gate, will porte cochere from a clock an aquarium in 2008 and a have early-morning access to tower. Inside the lobby, which waterpark in 2010, Legoland the park of up to an hour be- contains a “wading pond” California established itself as fore the general public is ad- filled with Lego bricks, several a serious player in Southern mitted. of the more than 3,500 elabo- California’s heated amuse- “This is a one-of-a-kind rate Lego models adorning the ment market. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

TOCN0004DIGIBKLT.Pdf

NORTHERN DANCES: FOLK MUSIC FROM SCANDINAVIA AND ESTONIA Gunnar Idenstam You are now entering our world of epic folk music from around the Baltic Sea, played on a large church organ and the nyckelharpa, the keyed Swedish fiddle, in a recording made in tribute to the new organ in the Domkirke (Cathedral) in Kristiansand in Norway. The organ was constructed in 2013 by the German company Klais, which has created an impressive and colourful instrument with a large palette of different sounds, from the most delicate and poetic to the most majestic and festive – a palette that adds space, character, volume and atmosphere to the original folk tunes. The nyckelharpa, a traditional folk instrument, has its origins in the sixteenth century, and its fragile, Baroque-like sound is happily embraced by the delicate solo stops – for example, the ‘woodwind’, or the bells, of the organ – or it can be carried, like an eagle flying over a majestic landscape, with deep forests and high mountains, by a powerful northern wind. The realm of folk dance is a fascinating soundscape of irregular pulse, ostinato- like melodic figures and improvised sections. The melodic and rhythmic variations they show are equally rich, both in the musical tradition itself and in the traditions of the hundreds of different types of dances that make it up. We have chosen folk tunes that are, in a more profound sense, majestic, epic, sacred, elegant, wild, delightful or meditative. The arrangements are not written down, but are more or less improvised, according to these characters. Gunnar Idenstam/Erik Rydvall 1 Northern Dances This is music created in the moment, introducing the mighty bells of the organ. -

At a Glance Concert Schedule

At A Glance Concert Schedule SC- Supper Club CH- Concert Hall MB- Music Box Full Venue RT- Rooftop Deck RF- Riverfront Porch PDR- Private Dining Room Wed 11/1 CH Paul Thorn Hammer & Nail 20th Anniversary Tour (Tickets) Thu 11/2 SC Johnny Cash Tribute by The Cold Hard Cash Show Spreading the great word and music of The Man in Black, Johnny Cash! (Tickets) Fri 11/3 CH Kevin Griffin of Better Than Ezra Singer, Guitarist, Alt-Rock Frontman (Tickets) Fri 11/3 SC Hey Mavis Northeast Ohio’s Favorite Americana Folk Rock Band (View Page) Sat 11/4 SC Sugar Blue "One of the foremost harmonica players of our time" - Rolling Stone (Tickets) Sun 11/5 SC Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Brunch Featuring Long Time Gone (View Page) Sun 11/5 CH Elizabeth Cook Outlaw Country Songstress (Tickets) Mon 11/6 CH Lucinda Williams ~ This Sweet Old World 1st set This Sweet Old World, 2nd set Hits & Favorites (View Page) Wed 11/8 SC Strange Tales From Ohio History – Neil Zurcher Cleveland Stories Dinner Parties (View Page) Wed 11/8 CH Tom Rush Blues-Influenced Folk Rocker and Songwriter (Tickets) Fri 11/10 SC Motown & More with Nitebridge Enjoy the jumpin' sounds of your favorite classic hits! (View Page) Fri 11/10 CH Neil Young Tribute by Broken Arrow Spot on rendition of Neil Young hits and standards (Tickets) Sun 11/12 SC Beatles Brunch With The Sunrise Jones (Tickets) Mon 11/13 CH Science Café – Beyond 0’s and 1’s: Using Chemical-Based Memory Devices for Large Scale Data Storage Talk Science, Drink Beer (View Page) Tue 11/14 CH The Electric Strawbs Electric Show -

Trollfågeln the Magic Bird

EMILIA AMPER Trollfågeln The Magic Bird BIS-2013 2013_f-b.indd 1 2012-10-02 11.28 Trollfågeln 1. Till Maria 5'00 2. G-mollpolska efter Anders Gustaf Jernberg 3'25 3. Ut i mörka natten 4'55 4. Isadoras land 3'50 5. Trollfuglen 2'25 6. Polska fra Hoffsmyran 4'02 7. Herr Lager och skön fager 3'08 8. Brännvinslåt från Torsås 2'40 9. Pigopolskan / Den glömda polskan 5'08 10. När som flickorna de gifta sig 4'05 11. Kapad 4'44 12. Bredals Näckapolska 3'01 13. Galatea Creek 3'19 14. Vals från Valsebo 8'56 TT: 59'42 Emilia Amper nyckelharpa, sång Johan Hedin nyckelharpa Anders Löfberg cello Dan Svensson slagverk, gitarr, sång Olle Linder slagverk, gitarr Helge Andreas Norbakken slagverk Stråkar ur TrondheimSolistene: Johannes Rusten och Daniel Turcina violin Frøydis Tøsse viola, Marit Aspaas cello Rolf Hoff Baltzersen kontrabas 2 Trollfågeln innehåller 14 spår som på många sätt illustrerar mig som person och mitt liv som musiker och kompositör. Här är musiken som jag brinner för, en brokig skara låtar där traditionella svenska polskor möter nykomponerad musik inspirerad av andra länders folk- musik, och av pop, rock och kammarmusik. Jag spelar och sjunger solo eller tillsammans med goda vänner från både folkmusik och klassiskt. Som 10-åring förälskade jag mig i nyckelharpan vid första ögonkastet! Barndomens direkta glädje av instrument och melodier övergick efterhand i ett växande intresse för folkmusiken som genre. Jag mötte musik och människor från hela världen, och för mig var det liksom samma språk vi alla talade, ett språk där kopplingen mellan musik och dans är direkt och självklar. -

New Harmonies

Dear Teacher: Welcome to New Harmonies: Celebrating American Roots Music, an exhibition organized by the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum on Main Street program and brought to you by your state humanities council. These materials and activities were compiled to help your students observe, imagine, learn & contribute to the discussion of American roots music during their visit to the exhibition. While it’s desirable to participate in each step, it’s certainly not required. In fact, each individual piece will provide your students with thought-provoking questions and activities. You can easily customize lessons or even develop your own methods of exploring roots music! The lesson plans that accompany New Harmonies will help you create a meaningful experience for your students. Each includes Pre-visit, Visit, and Post-visit activities. All the lessons can be adapted for younger or older audiences, so evaluate each lesson before selecting activities for your students. The Pre-visit step is designed to be simple, to introduce the students to the exhibit topic, and to be easy to implement. This step is intended to stimulate the students’ curiosity and help students gather information for use in visit and post-visit activities. The Visit step is focused on information gathering. This is a time for the students to explore and read the exhibit content, enjoy audio samples, and utilize interactive components. The activity worksheets included in this section will help students gather enough information to apply their knowledge in a later classroom activity. With all activities and worksheets, students can work individually or in groups. The Post-visit step consists of ideas and activities to implement after your return to the classroom. -

Color Front Cover

COLOR FRONT COVER COLOR CGOTH IS I COLOR CGOTH IS II COLOR CONCERT SERIES Welcome to our 18th Season! In this catalog you will find a year's worth of activities that will enrich your life. Common Ground on the Hill is a traditional, roots-based music and arts organization founded in 1994, offering quality learning experiences with master musicians, artists, dancers, writers, filmmakers and educators while exploring cultural diversity in search of a common ground among ethnic, gender, age, and racial groups. The Baltimore Sun has compared Common Ground on the Hill to the Chautauqua and Lyceum movements, precursors to this exciting program. Our world is one of immense diversity. As we explore and celebrate this diversity, we find that what we have in common with one another far outweighs our differences. Our common ground is our humanity, often best expressed by artistic traditions that have enriched human experience through the ages. We invite you to join us in searching for common ground as we assemble around the belief that we can improve ourselves and our world by searching for the common ground in one another, through our artistic traditions. In a world filled with divisive, negative news, we seek to discover, create and celebrate good news. How we have grown! Common Ground on the Hill is a multifaceted year-round program, including two separate Traditions Weeks of summer classes, concerts and activities, held on the campus of McDaniel College, two separate Music and Arts festivals held at the Carroll County Farm Museum, two seven-event Monthly Concert Series held in Westminster and Baltimore, and a new program this summer at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Common Ground on Seminary Ridge. -

Atletscorer Loaded 2012

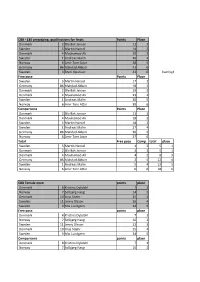

CBB - 180 prejudging, qualifications for finals Points Place Danmark 2 Ole Bak Jensen 11 1 Sweden 5 Martin Hanzel 14 2 Denmark 4 Mouhamad Ali 20 3 Sweden 1 Andreas Malm 26 4 Norway 6 Amir Tore Attar 38 5 Germany 86 Mahdad Akbari 43 6 Sweden 3 Brani Oparusic 43 6 had highest individual score Free pose Points Place Sweden 5 Martin Hanzel 17 1 Germany 86 Mahdad Akbari 18 2 Danmark 2 Ole Bak Jensen 19 3 Denmark 4 Mouhamad Ali 23 4 Sweden 1 Andreas Malm 30 5 Norway 6 Amir Tore Attar 39 6 Comparisons Points Place Danmark 2 Ole Bak Jensen 11 1 Denmark 4 Mouhamad Ali 18 2 Sweden 5 Martin Hanzel 18 2 Sweden 1 Andreas Malm 27 4 Germany 86 Mahdad Akbari 36 5 Norway 6 Amir Tore Attar 37 6 Total Free pose Comp. total place Sweden 5 Martin Hanzel 1 2 5 1 Danmark 2 Ole Bak Jensen 3 1 5 1 Denmark 4 Mouhamad Ali 4 2 8 3 Germany 86 Mahdad Akbari 2 5 12 4 Sweden 1 Andreas Malm 5 4 13 5 Norway 6 Amir Tore Attar 6 6 18 6 CBB Female open points place Denmark 8 Kristina Dybdahl 7 1 Norway 7 Solbjørg Haug 14 2 Denmark 10 Anja Stæhr 25 3 Sweden 11 Jenny Olsson 26 4 Sweden 9 Mia Lundgren 34 5 Free pose points place Denmark 8 Kristina Dybdahl 7 1 Norway 7 Solbjørg Haug 16 2 Sweden 11 Jenny Olsson 21 3 Denmark 10 Anja Stæhr 25 4 Sweden 9 Mia Lundgren 34 5 Comparisons points place Denmark 8 Kristina Dybdahl 7 1 Norway 7 Solbjørg Haug 16 2 Denmark 10 Anja Stæhr 22 3 Sweden 11 Jenny Olsson 25 4 Sweden 9 Mia Lundgren 34 5 total free posing comp.