Pastoral and Nomadic Tribes at the Beginning of the First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Horse Bridle with Cheekpieces As a Marker of Social Change: an Experimental and Statistical Study T

Journal of Archaeological Science 97 (2018) 125–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Early horse bridle with cheekpieces as a marker of social change: An experimental and statistical study T ∗ Igor V. Chechushkova, , Andrei V. Epimakhovb,c, Andrei G. Bersenevd a Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh, 3302 WWPH, Pittsburgh, PA, 15260, USA b Research Educational Centre for Eurasian Research, South Ural State University, Lenina av., 76, Chelyabinsk, 454000, Russia c Institute of History and Archaeology of the Ural Branch of RAS, Kovalevskaya st., 16, Ekaterinburg, 620990, Russia d Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation for Chelyabinsk Region, 3rd International st., 116, Chelyabinsk, 454000, Russia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The morphological similarities/dissimilarities between antler and bone-made cheekpieces have been employed Cheekpieces in several studies to construct a relative chronology for Bronze Age Eurasia. Believed to constitute a part of the Chariot horse bit, the cheekpieces appear in ritual contexts everywhere from the Mycenaean Shaft Graves to the Bronze Bronze age Age kurgan cemeteries in Siberia. However, these general understandings of the function and morphological Experimental archaeology changes of cheekpieces have never been rigorously tested. This paper presents statistical analyses (e.g., simi- Use-wear larities, multidimensional scaling, and cluster analysis) that document differences in cheekpiece morphology, comparing shield-like, plate-formed, and rod-shaped types in the context of temporal change and spatial var- iation. We investigated changes in function over time through the use of experimental replicas used in bridling horses. -

Ulug-Depe and the Transition Period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia

Ulug-depe and the transition period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia. A tribute to V.I. Sarianidi Johanna Lhuillier To cite this version: Johanna Lhuillier. Ulug-depe and the transition period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia. A tribute to V.I. Sarianidi . Dubova, N.A., Antonova, E.V., Kozhin, P.M., Kosarev, M.F., Muradov, R.G., Sataev, R.M. & Tishkin A.A. Transactions of Margiana Archaeological Expedition, To the memory of Professor Viktor Sarianidi, 6, Staryj Sad, pp.509-521, 2016, 978-5-89930-150-6. halshs-01534928 HAL Id: halshs-01534928 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01534928 Submitted on 8 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N.N. MIKLUKHO-MAKLAY INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY OF RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES MARGIANA ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION ALTAY STATE UNIVERSITY TRANSACTIONS OF MARGIANA ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION Volume 6 To the Memory of Professor Victor Sarianidi Editorial board N.A. Dubova (editor in chief), E.V. Antonova, P.M. Kozhin, M.F. Kosarev, R.G. Muradov, R.M. Sataev, A.A. Tishkin Moscow 2016 Туркменистан, Гонур-депе, 9 октября 2005 г. -

A Study on the Scythian Torque

IJCC, Vol, 6, No. 2, 69〜82(2003) A Study on the Scythian Torque Moon-Ja Kim Professor, Dept, of Clothing & Textiles, Suwon University (Received May 2, 2003) Abstract The Scythians had a veritable passion for adornment, delighting in decorating themselves no less than their horses and belongings. Their love of jewellery was expressed at every turn. The most magnificent pieces naturally come from the royal tombs. In the area of the neck and chest the Scythian had a massive gold Torques, a symbol of power, made of gold, turquoise, cornelian coral and even amber. The entire surface of the torque, like that of many of the other artefacts, is decorated with depictions of animals. Scythian Torques are worn with the decorative terminals to the front. It was put a Torque on, grasped both terminals and placed the opening at the back of the neck. It is possible the Torque signified its wearer's religious leadership responsibilities. Scythian Torques were divided into several types according to the shape, Torque with Terminal style, Spiral style, Layers style, Crown style, Crescent-shaped pectoral style. Key words : Crescent-shaped pectoral style, Layers style, Scythian Torque, Spiral style, Terminal style role in the Scythian kingdom belonged to no I • Introduction mads and it conformed to nomadic life. A vivid description of the burial of the Scythian kings The Scythians originated in the central Asian and of ordinary members of the Scythian co steppes sometime in the early first millennium, mmunity is contained in Herodotus' History. The BC. After migrating into what is present-day basic characteristics of the Scythian funeral Ukraine, they flourished, from the seventh to the ritual (burials beneath Kurgans according to a third centuries, BC, over a vast expanse of the rite for lating body in its grave) remained un steppe that stretched from the Danube, east changed throughout the entire Scythian period.^ across what is modem Ukraine and east of the No less remarkable are the articles from the Black Sea into Russia. -

INDO-EUROPEAN COMMUNICATIONS: the MODEL of “NOMADIC HOMELAND” Victor A

Periódico do Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas sobre Gênero e Direito Centro de Ciências Jurídicas - Universidade Federal da Paraíba V. 9 - Nº 04 - Ano 2020 ISSN | 2179-7137 | http://periodicos.ufpb.br/ojs2/index.php/ged/index 427 INDO-EUROPEAN COMMUNICATIONS: THE MODEL OF “NOMADIC HOMELAND” Victor A. Novozhenov1 Elina K. Altynbekova2 Aibek Zh. Sydykov3 Abstract: The authors of the article (Europe and Ural-Kazakh steppes) by studied the origin of Indo-European two main ways (north and south) through tribes in the light of ancient Margiana and Transcaucasia. communications and the spread of the tribes according to wheeled transport Keywords: steppeland culture, relics in the steppe zone of Eastern migrations, wheeled transport, cattle- Eurasia. The authors considered some breeding, tin-mettallurgy, clan- modern theories related to Indo- leadership. European (IE) and Indo-Iranian (IIr) origin, defined IE innovations that 1. Introduction. marked the territories as possible Recently, in connection with homelands for IEs, and localized them the publication of the new paleogenetic on the map and. The authors used the results [Allentoft et al, 2015; Haak et al., method of mapping and analysing of IE 2015; Lazaridis et al, 2014; 2017; innovations for localization of possible Damgaard et al, 2018a; 2018b; Goldberg homeland teritories of IE on the maps et al, 2017], there is sharp increase in the and substantiate the polycentric model of interest of Russian-speaking scholars to the ancestral homeland of IE as model of the problems of IE culture and origin “nomadic homeland”. According to this [http://генофонд.рф/?page_id=3949 model, the IE homeland was localized in Novozhenov, 2015e; Klejn et al, the steppe-lands of Eurasian continent, 2017:71-15]. -

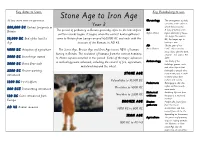

Bronze Age Iron Age Anglo-Saxons the Mayflower Thames Tunnel The

Monday 11th – Friday 15th May 2020 History Think about what the word ancient means. Which description below do you think is the most accurate? 1. Ancient means a period of time five years ago. 2. Ancient means a period of time five hundred years ago. 3. Ancient means a period of time five thousand years ago. This half term, we will be looking at a time in history when people lived many thousands of years ago. People who lived many thousands of years ago lived in what we call ancient times. There were three main time periods (long lengths of time) in ancient times in Britain (the country we live in). We call these periods of time the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. Bronze and iron are types of metal. Why do you think these periods of time were named after metals? Look at the pictures below. Can you match the ancient artefact (object) to the right time period? What clues can you see? We will be looking in more detail at the Bronze Age and Iron Age – they both happened after the Stone Age. The Bronze Age began around 2,100BCE (over 4,000 years ago). It lasted for around 1500 years until 750BCE when the Iron Age began. Bronze Age Anglo-Saxons Thames Tunnel 2,100BCE 750BCE 55BCE 0 410 1620 1825 1940 2020 Iron Age The Mayflower The Blitz Just like the Stone Age when early humans made tools from stone, the Bronze Age was called that because humans started making tools from…bronze! The Bronze Age started at different times around the world – depending on when humans in different countries discovered how to make bronze by mixing other metals together. -

Biocolonization of Stone: Control and Preventive Methods Proceedings from the MCI Workshop Series

Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press smithsonian contributions to museum conservation • number 2 Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press BiocolonizationA Chronology of Stone:of MiddleControl Missouri and Preventive Plains VillageMethods Sites Proceedings from the MCI Workshop Series By CraigEdited M. Johnsonby withA. Elenacontributions Charola, by Stanley ChristopherA. Ahler, Herbert Haas,McNamara, and Georges Bonani and Robert J. Koestler SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of “diffusing knowledge” was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: “It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge.” This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to History and Technology Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report on the research and collections of its various museums and bureaus. The Smithsonian Contributions Series are distributed via mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institu- tions throughout the world. Manuscripts submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press from authors with direct affilia- tion with the various Smithsonian museums or bureaus and are subject to peer review and review for compliance with manuscript preparation guidelines. -

Documenting Carved Stones by 3D Modelling

Documenting carved stones by 3D modelling – Example of Mongolian deer stones Fabrice Monna, Yury Esin, Jérôme Magail, Ludovic Granjon, Nicolas Navarro, Josef Wilczek, Laure Saligny, Sébastien Couette, Anthony Dumontet, Carmela Chateau Smith To cite this version: Fabrice Monna, Yury Esin, Jérôme Magail, Ludovic Granjon, Nicolas Navarro, et al.. Documenting carved stones by 3D modelling – Example of Mongolian deer stones. Journal of Cultural Heritage, El- sevier, 2018, 34 (November–December), pp.116-128. 10.1016/j.culher.2018.04.021. halshs-01916706 HAL Id: halshs-01916706 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01916706 Submitted on 22 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328759923 Documenting carved stones by 3D modelling-Example of Mongolian deer stones Article in Journal of Cultural Heritage · May 2018 DOI: 10.1016/j.culher.2018.04.021 CITATIONS READS 3 303 10 authors, including: Fabrice Monna Yury Esin University -

Stone Age to Iron Age All Dates Shown Below Are Approximate

Key dates to learn: Key Vocabulary to use: Stone Age to Iron Age All dates shown below are approximate. Chronology The arrangement of dates or events in the order in 800,000 BC Earliest footprints in Year 3 which they occurred. Britain The period of prehistory in Britain generally refers to the time before BC A way of dating years written records began. It begins when the earliest hunter-gatherers Before Christ before the birth of Jesus. The bigger the number 10,000 BC End of the last Ice came to Britain from Europe around 450,000 BC and ends with the BC, the longer ago in Age invasion of the Romans in AD 43. history is was. AD “In the year of our 4000 BC Adoption of agriculture The Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age covers 98% of human Anno Domini Lord”. AD is used to show dates after the birth history in Britain. The evolution of humans from the earliest hominins of Jesus. This year is AD 3000 BC Stonehenge started to Homo sapiens occurred in this period. Some of the major advances 2019. in technology were achieved, including the control of fire, agriculture, Archaeology The study of the 3000 BC Skara Brae built buildings, graves, tools metalworking and the wheel. and other objects that 2300 BC Bronze working belonged to people who STONE AGE lived in the past, in order introduced to learn about their Palaeolithic to 10,000 BC culture and society. 1200 BC First hillforts Prehistoric Belonging to the time Mesolithic to 4000 BC before written records 800 BCE Ironworking introduced were made. -

Andronovo Problem: Studies of Cultural Genesis in the Eurasian Bronze Age

Open Archaeology 2021; 7: 3–36 Review Stanislav Grigoriev* Andronovo Problem: Studies of Cultural Genesis in the Eurasian Bronze Age https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2020-0123 received June 8, 2020; accepted November 28, 2020. Abstract: Andronovo culture is the largest Eurasian formation in the Bronze Age, and it had a significant impact on neighboring regions. It is the important culture for understanding many historical processes, in particular, the origins and migration of Indo-Europeans. However, in most works there is a very simplified understanding of the scientific problems associated with this culture. The history of its study is full of opposing opinions, and all these opinions were based on reliable grounds. For a long time, the existence of the Andronovo problem was caused by the fact that researchers supposed they might explain general processes by local situations. In fact, the term “Andronovo culture” is incorrect. Another term “Andronovo cultural-historical commonality” also has no signs of scientific terminology. Under these terms a large number of cultures are combined, many of which were not related to each other. In the most simplified form, they can be combined into two blocks that existed during the Bronze Age: the steppe (Sintashta, Petrovka, Alakul, Sargari) and the forest-steppe (Fyodorovka, Cherkaskul, Mezhovka). Often these cultures are placed in vertical lines with genetic continuity. However, the problems of their chronology and interaction are very complicated. By Andronovo cultures we may understand only Fyodorovka and Alakul cultures (except for its early stage); however, it is better to avoid the use of this term. Keywords: Andronovo culture, history of study, Eurasia 1 Introduction The Andronovo culture of the Bronze Age is the largest archaeological formation in the world, except for the cultures of the Scytho-Sarmatian world of the Early Iron Age. -

Unit 10 Chalcolithic and Early Iron Age-I

UNIT 10 CHALCOLITHIC AND EARLY IRON AGE-I Structure 10.0 Objectives 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Ochre Coloured Pottery Culture 10.3 The Problems of Copper Hoards 10.4 Black and Red Ware Culture 10.5 Painted Grey Ware Culture 10.6 Northern Black Polished Ware Culture 10.6.1 Structures 10.6.2 Pottery 10.6.3 Other Objects 10.6.4 Ornaments 10.6.5 Terracotta Figurines 10.6.6 Subsistence Economy and Trade 10.7 Chalcolithic Cultures of Western, Central and Eastern India 10.7.1 Pottery: Diagnostic Features 10.7.2 Economy 10.7.3 Houses and Habitations 10.7.4 Other 'characteristics 10.7.5 Religion/Belief Systems 10.7.6 Social Organization 10.8 Let Us Sum Up 10.9 Key Words 10.10 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 10.0 OBJECTIVES In Block 2, you have learnt about'the antecedent stages and various aspects of Harappan culture and society. You have also read about its geographical spread and the reasons for its decline and diffusion. In this unit we shall learn about the post-Harappan, Chalcolithic, and early Iron Age Cultures of northern, western, central and eastern India. After reading this unit you will be able to know about: a the geographical location and the adaptation of the people to local conditions, a the kind of houses they lived in, the varieties of food they grew and the kinds of tools and implements they used, a the varietie of potteries wed by them, a the kinds of religious beliefs they had, and a the change occurring during the early Iron age. -

Barbaric Splendour: the Use of Image Before and After Rome Comprises a Collection of Essays Comparing Late Iron Age and Early Medieval Art

Martin with Morrison (eds) Martin with Morrison Barbaric Splendour: the use of image before and after Rome comprises a collection of essays comparing late Iron Age and Early Medieval art. Though this is an unconventional approach, Barbaric Splendour there are obvious grounds for comparison. Images from both periods revel in complex compositions in which it is hard to distinguish figural elements from geometric patterns. Moreover, in both periods, images rarely stood alone and for their own sake. Instead, they decorated other forms of material culture, particularly items of personal adornment and The use of image weaponry. The key comparison, however, is the relationship of these images to those of Rome. Fundamentally, the book asks what making images meant on the fringe of an expanding or contracting empire, particularly as the art from both periods drew heavily before and after Rome from – but radically transformed – imperial imagery. Edited by Toby Martin currently works as a lecturer at Oxford University’s Department for Continuing Education, where he specialises in adult and online education. His research concentrates on theoretical and interpretative aspects of material culture in Early Medieval Europe. Toby Toby F. Martin with Wendy Morrison has also worked as a field archaeologist and project officer in the commercial archaeological sector and continues to work as a small finds specialist. Wendy Morrison currently works for the Chilterns Conservation Board managing the NLHF funded Beacons of the Past Hillforts project, the UK’s largest high-res archaeological LiDAR survey. She also is Senior Associate Tutor for Archaeology at the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education. -

The “Steppe Belt” of Stockbreeding Cultures in Eurasia During the Early Metal Age

TRABAJOS DE PREHISTORIA 65, N.º 2, Julio-Diciembre 2008, pp. 73-93, ISSN: 0082-5638 doi: 10.3989/tp.2008.08004 The “Steppe Belt” of stockbreeding cultures in Eurasia during the Early Metal Age El “Cinturón estepario” de culturas ganaderas en Eurasia durante la Primera Edad del Metal Evgeny Chernykh (*) ABSTRACT estepario” sucedió en una fecha tan tardía como los si- glos XVIII- XIX AD. The stock-breeding cultures of the Eurasian “steppe belt” covered approximately 7-8 million square km2 from Key words: Nomadic stock-breeding cultures; Eurasia; the Lower Danube in the West to Manchuria in the East Early Metal Age; Archaeometallurgy; Radiocarbon chro- (a distance of more than 8000 km). The initial formation nology. of the “steppe belt’cultures coincided with the flourishing of the Carpatho-Balkan metallurgical province (V millen- Palabras clave: Culturas ganaderas nómadas; Eurasia; nium BC). These cultures developed during the span of Primera Edad del Metal; Arqueometalurgia; Cronología the Circumpontic metallurgical province (IV-III millen- radiocarbónica. nium BC). Their maturation coincided with the activity of the various centers of the giant Eurasian and East-Asian metallurgical provinces (II millennium BC). The influ- ence of these stock-breeding nomadic cultures on the his- I. INTRODUCTORY NOTES: THE VIEW torical processes of Eurasian peoples was extremely OF A HISTORIAN AND strong. The collapse of the “steppe belt” occurred as late ARCHEOLOGIST as the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries AD. Modern research shows that at their apogee the stockbreeding cultures of the Eurasian RESUMEN “steppe belt” covered a gigantic territory. From West to East, from the Middle Danube basin to Las culturas ganaderas del “cinturón estepario” de Manchuria the distances exceeded 8000 kilome- Eurasia cubrieron aproximadamente 7-8 millones de ters without any noticeable breaks.