Margaret Mackall Smith Taylor, First Lady 1788-1852

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defining the Role of First Lady

- Defining the Role of First Lady An Honors College Thesis (Honors 499) By Denise Jutte - Thesis Advisor Larry Markle Ball State University Muncie, IN Graduation Date: May 3, 2008 ;' l/,~· ,~, • .L-',:: J,I Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction: Defining the Role of First Lady 4 First Ladies Ranking 11 Individual Analysis of First Ladies 12 Chronological Order Observations on Leadership and Comparisons to Previous Presidential Rankings 177 Conclusion: The Role ofthe Future First Spouse 180 Works Cited 182 Appendix A: Ranking of Presidents 183 Appendix B: Presidential Analysis 184 Appendix C: Other Polls and Rankings of the First Ladies 232 1 Abstract In the Fall Semester of 2006, I took an honors colloquium taught by Larry Markle on the presidents of the United States. Throughout the semester we studied all of the past presidents and compiled a ranked list of these men based on our personal opinion of their greatness. My thesis is a similar study of their wives. The knowledge I have gained through researching presidential spouses has been very complementary to the information I learned previously in Mr. Markle's class and has expanded my understanding of one ofthe most important political positions in the United States. The opportunity to see what parallels developed between my ran kings of the preSidents and the women that stood behind them has led me to a deeper understanding ofthe traits and characteristics that are embodied by those viewed as great leaders. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dad for helping me to participate in and understand the importance of history and education at a young age. -

Bailing of Jeff Davis

CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM By George P. Lathrop Shortly after daybreak of a morning star near the end of June 1865, Horace Greeley came to the house of George Shea (then Corporation Attorney, and afterwards Chief- Justice of the Marine Court), in New York. His errand was urgent. The preceding day he had received a letter, dated June 22, from Mrs. Varina Davis, whose husband, Jefferson Davis, was a prisoner at Fort Monroe. The “Bureau of Military Justice”, headed by General Joseph Holt, had already charged him with guilty knowledge concerning the assassination of Lincoln. Mrs. Davis wrote from Savannah, and implored Greeley to obtain, if possible, a speedy public trial of Davis on this charge, and on any inferred charge of cruelty to prisoners of war. Greeley could not believe that Davis had anything to do with the assassination. He added that Davis had personally received from Francis P. Blair, in the preceding winter, sufficient assurance of Lincoln’s kindly intentions toward the South. He then asked Mr. Shea to interest himself professionally on Davis’s behalf and said : “We can have with us those with whom you have been in confidential relations during the last two years”. Shea said that unless the Government were willing to abandon the charge against Wirz for cruelty to prisoners, it could not overlook his superior, Davis, popularly supposed to be responsible. He should hesitate to act as counsel, if the case came before a military tribunal. Greeley said he did not know Mr. Davis, and Shea said : “Neither do I. But I know those who are intimate with him ; and his reputation among them is universal for kindness of heart amounting, in a ruler, almost to weakness.” Greeley feared that the head of the Confederacy could not be held blameless, and that Wirz’s impending trial had a “malign aspect” for Davis. -

Eighth Grade Social Studies

Eighth Grade Social Studies Activity 2 knoxschools.org/kcsathome 8th Grade Social Studies *There will be a short video lesson of a Knox County teacher to accompany this task available on the KCS YouTube Channel and KCS TV. Grade: 8th Topic: Civil War Leaders Goal(s): Identify the roles and significant contributions of Civil War leaders. Standards: 8.62 & 8.63 (in part) The Better Leader Task Directions: Using your background knowledge, information from the videoed lesson, the attached biographies, and from the Battlefields website, complete the chart and questions below. Write the three characteristics of a leader that you think are the most important. 1. 2. 3. Abraham Lincoln Jefferson Davis Ulysses S. Grant Robert E. Lee Union or Confederate? How did his leadership role change throughout the course of the war? How did he become a “national” leader? What was his major accomplishment(s) of the Civil War? What kind of impact did they have on their side/country? How could the war have been different if he didn’t exist? Now that you have dug deeper into the leadership of the four most familiar leaders of the Civil War, consider each man’s leadership during the war. Which leader do you think best meets the characteristics of a good leader and explain why? United States President Abraham Lincoln Biography from the American Battlefield Trust Abraham Lincoln, sixteenth President of the United States, was born near Hodgenville, Kentucky on February 12, 1809. His family moved to Indiana when he was seven and he grew up on the edge of the frontier. -

Zachary Taylor 1 Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor 1 Zachary Taylor Zachary Taylor 12th President of the United States In office [1] March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850 Vice President Millard Fillmore Preceded by James K. Polk Succeeded by Millard Fillmore Born November 24, 1784Barboursville, Virginia Died July 9, 1850 (aged 65)Washington, D.C. Nationality American Political party Whig Spouse(s) Margaret Smith Taylor Children Ann Mackall Taylor Sarah Knox Taylor Octavia Pannill Taylor Margaret Smith Taylor Mary Elizabeth (Taylor) Bliss Richard Taylor Occupation Soldier (General) Religion Episcopal Signature Military service Nickname(s) Old Rough and Ready Allegiance United States of America Service/branch United States Army Years of service 1808–1848 Rank Major General Zachary Taylor 2 Battles/wars War of 1812 Black Hawk War Second Seminole War Mexican–American War *Battle of Monterrey *Battle of Buena Vista Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President of the United States (1849-1850) and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass. Taylor was the last President to hold slaves while in office, and the last Whig to win a presidential election. Known as "Old Rough and Ready," Taylor had a forty-year military career in the United States Army, serving in the War of 1812, the Black Hawk War, and the Second Seminole War. He achieved fame leading American troops to victory in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Monterrey during the Mexican–American War. As president, Taylor angered many Southerners by taking a moderate stance on the issue of slavery. -

John Taylor Wood: Man of Action, Man of Honor

The Cape Fear Civil War Round Table John Taylor Wood: Man of Action, Man of Honor By Tim Winstead History 454 December 4, 2009 On July 20, 1904, a short obituary note appeared on page seven of the New York Times. It simply stated, "Captain John Taylor Wood, grandson of President Zachary Taylor and nephew of Jefferson Davis, died in Halifax, N.S. yesterday, seventy-four years old." The note also stated that Wood served as a United States Navy midshipman, fought in the Mexican War, served as a Confederate army colonel on the staff of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee's army, escaped the collapse of the Confederacy with General Breckinridge to Cuba, and was a resident of Halifax, Nova Scotia when he passed. In one paragraph, the obituary writer prepared the outline of the life of a man who participated in many of the major events of the American Civil War. John Taylor Wood's story was much more expansive and interwoven with the people and history of the Civil War era than the one paragraph credited to him by the Times. This paper examined the events in which Wood found himself immersed and sought to determine his role in those events. The main focus of the paper was Wood's exploits during his service to the Confederate States of America. His unique relationships with the leadership of the Confederacy ensured that he was close at hand when decisions were made which affected the outcome of the South's gamble for independence. Was John Taylor Wood the Forrest Gump of his day? Was it mere chance that Wood was at Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, at Drewry's Bluff on May 15, 1862, abroad the USS Satellite in August 1863, aboard the USS Underwriter at New Berne in February 1864, abroad the CSS Tallahassee in August 1864, or with Jefferson Davis on the "unfortunate day" in Georgia on May 10, 1865? Was it only his relationship with Jefferson Davis that saw Wood engaged in these varied events? This paper examined these questions and sought to establish that it was Wood's competence and daring that placed him at the aforementioned actions and not Jefferson Davis's nepotism. -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ). -

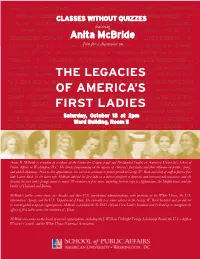

Classes Without Quizzes-Edited

MARTHA WAS H INGTON A BIGA IL A DA M S MARTHA JEFFERSON DOLLEY MADISON S S ELISZ WABETHO MONROE LSO UISA A D A M S RACHEL JAC KS O N H ANNA H VA N B UREN A N NA H A RRIS O N featuring L ETITI A T YLER JULIA T YLE R S A R AH P OLK MARG A RET TAY L OR AnBIitGaAIL FcILBL MrOREide J A N E PIER C E 11 12 H A RRIET L ANE MAR YJoin T ODDfor a discussion L INC OonL N E LIZ A J OHN S O N JULIA GRANT L U C Y H AY E S LUC RETIA GARFIELD ELLEN ARTHUR FRANCES CLEVELAND CAROLINE HARRISON 10 IDA MCKINLEY EDITH ROOSEVELT HELEN TAFT ELLEN WILSON photographers, presidential advisers, and social secretaries to tell the stories through “Legacies of America’s E DITH WILSON F LORENCE H ARDING GRACE COOLIDGE First Ladies conferences LOU HOOVER ELEANOR ROOSEVELT ELIZABETH “BESS”TRUMAN in American politics and MAMIE EISENHOWER JACQUELINE KENNEDY CLAUDIA “LADY for their support of this fascinating series.” history. No place else has the crucial role of presidential BIRD” JOHNSON PAT RICIA “PAT” N IXON E LIZABET H “ BETTY wives been so thoroughly and FORD ROSALYN C ARTER NANCY REAGAN BARBAR A BUSH entertainingly presented.” —Cokie Roberts, political H ILLARY R O DHAM C L INTON L AURA BUSH MICHELLE OBAMA “I cannot imagine a better way to promote understanding and interest in the experiences of commentator and author of Saturday, October 18 at 2pm MARTHA WASHINGTON ABIGAIL ADAMS MARTHA JEFFERSON Founding Mothers: The Women Ward Building, Room 5 Who Raised Our Nation and —Doris Kearns Goodwin, presidential historian DOLLEY MADISON E LIZABETH MONROE LOUISA ADAMS Ladies of Liberty: The Women Who Shaped Our Nation About Anita McBride Anita B. -

Varina Ann Banks Howell Davis (1.4.1.2.4.7.2) - First Lady of the Confederacy

Varina Ann Banks Howell Davis (1.4.1.2.4.7.2) - First Lady of the Confederacy This past November I attended my first D.A.R. meeting which celebrated Veterans Day with the local S.A. R. chapter here in Springfield Missouri. I was welcomed by mothers and daughters, descendants of American Revolutionary patriots, who were sharing stories about their colonial histories that intertwined with our own Robinett history. It began to dawn on me, an avid genealogist and fan of DNA studies, that a great deal of our own American story is carried not only down the Y DNA or male line, but it is preserved culturally and historically just as easily on the mother-daughter lines. Although genetically we cannot trace absolute matches this way within a surname, history does continue. As I look at my own daughter Chiara, I think of how this will be of value to her, and her family one day. So began my quest to learn more about our own D.A.R., daughters of Allen Robinett, or in this case of Allen and Margaret Symm Robinett. Not a lot has been published to date about A&M‘s first daughter, Susanna, but we do know that she married in England before coming to America Robert Ward and settled in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. There is extensive information available about the Ward families available on line. If you are interested to learn more about their roots try the Cecil County historical society. Annapolis Maryland is another location that needs extensive exploration…oh and by the way summer is a good time to visit, crab season you know. -

American First Ladies

AMERICAN FIRST LADIES Their Lives and Their Legacy edited by LEWIS L. GOULD GARLAND PUBLISHING, INC. NewYork S^London 1996 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction:The First Lady as Symbol and Institution Lewis L. Gould MarthaWashington 2 Patricia Brady Abigail Adams 16 Phyllis Lee Levin Dollej Madison 45 Holly Cowan Shulman Elizabeth Monroe 69 Julie K. Fix Louisa Adams 80 Lynn Hudson Parsons CONTENTS Anna Harrison 98 Nancy Beck Young LetitiaTyler 109 Melba Porter Hay Julia Tyler 111 Melba Porter Hay Sarah Polk 130 Jayne Crumpler DeFiore Margaret Taylor 145 Thomas H. Appleton Jr. Abigail Eillmore 154 Kristin Hoganson Jane Pierce 166 Debbie Mauldin Cottrell Mary Todd Lincoln 174 Jean H. Baker Eliza Johnson 191 Nancy Beck Young CONTENTS Julia Grant 202 John Y. Simon Lucy Webb Hayes 216 Olive Hoogenboom Lucretia Garfield 230 Allan Peskin Frances Folsom Cleveland 243 Sue Severn Caroline Scott Harrison 260 Charles W. Calhoun Ida Saxton McKinley 211 JohnJLeJfler Edith Kermit Roosevelt 294 Stacy A. Cordery Helen Herr on Toft 321 Stacy A. Cordery EllenAxsonWilson 340 Shelley Sallee CONTENTS Edith BollingWilson 355 Lewis L. Gould Florence Kling Harding 368 Carl Sferrazza Anthony Grace Goodhue Coolidge 384 Kiistie Miller Lou Henry Hoover 409 Debbie Mauldin Cottrell J Eleanor Roosevelt 422 Allida M. Black Bess Truman 449 Maurine H. Beasley Mamie Eisenhower 463 Martin M. Teasley Jacqueline Kennedy 416 Betty Boyd Caroli Lady Bird Johnson 496 Lewis L. Gould CONTENTS Patricia Nixon 520 Carl SJerrazza Anthony Betty Ford 536 John Pope Rosalynn Carter 556 Kathy B. Smith Nancy Reagan 583 James G. Benzejr. Barbara Bush 608 Myra Gutin Hillary Rodham Clinton 630 ^ Lewis L. -

The Forging of Civil War Memory and Reconciliation, 1865 – 1940

A Dissertation entitled “The Sinews of Memory:” The Forging of Civil War Memory and Reconciliation, 1865 – 1940 by Steven A. Bare Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History ___________________________________________ Dr. Kim E. Nielsen, Committee Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Ami Pflugrad-Jackisch, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Dr. Bruce Way, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Dr. Neil Reid, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Dr. Cyndee Gruden, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2019 Copyright 2019, Steven A. Bare This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of “The Sinews of Memory:” The Forging of Civil War Memory and Reconciliation, 1865 – 1940 by Steven A. Bare Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History The University of Toledo December 2018 “The Sinews of Memory:’ The Forging of Civil War Memory and Reconciliation, 1865 – 1940,” explores the creation of historical memory of the American Civil War and, its byproduct, reconciliation. Stakeholders in the historical memory formation of the war and reconciliation were varied and many. “The Sinews of Memory” argues reconciliation blossomed from the 1880s well into the twentieth-century due to myriad of historical forces in the United States starting with the end of the war leading up to World War II. The crafters of the war’s memory and reconciliation – veterans, women’s groups, public history institutions, governmental agents, and civic boosters – arrived at a collective memory of the war predicated on notions of race, manliness, nationalism, and patriotism. -

Zoom in on America American First Ladies the Office of the First Lady Did Not Formally Exist Until the Presidency of Jimmy Carter in the 1970S

September 2014 A Monthly Publication of the U.S. Consulate Krakow Volume X. Issue 119 f i r s t l a d i e s Jacqueline Kennedy (AP Photo) In this issue: American First Ladies Zoom in on America American First Ladies The Office of the First Lady did not formally exist until the presidency of Jimmy Carter in the 1970s. First Ladies have, however, played a vital role since the founding of the United States. There have been 49 First Ladies in the history of the United States, and each has left an imprint on the presidency. With the passing of time, the role of the first Lady has risen in prominence. Along with women’s emancipation and the equal rights movement, the role of the First Lady also has changed significantly. Below is a list of the women who acted as First Ladies since 1789. Not all of the First Ladies were wives of the presidents. In a few cases, U.S. presidents were widowers when they took office or became widowers during office. In such cases a female relative played the role of First Lady. THE FIRST LADY YEARS OF TENURE Martha Dandridge Custis Washington (1731-1802), wife of George Washington 1789 - 1797 Abigail Smith Adams (1744 - 1818), wife of John Adams 1797 - 1801 Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772 - 1836), daughter of Thomas Jefferson 1801 - 1809 Dolley Payne Todd Madison (1768 - 1849), wife of James Madison 1809 - 1817 Elizabeth Kortright Monroe (1768 - 1830), wife of James Monroe 1817 - 1825 Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams (1775 - 1852), wife of John Quincy Adams 1825 - 1829 Emily Donelson (1807 - 1836), niece of Andrew Jackson 1829 - 1834 Sarah Jackson (1803 - 1887), daughter-in-law of Andrew Jackson 1834 - 1837 Angelica Van Buren (1818 - 1877), daughter-in-law of Martin Van Buren 1839 - 1841 Anna Tuthill Symmes Harrison (1775 - 1864), wife of William Henry Harrison 1841 - 1841 Letitia Christian Tyler(1790 - 1842), wife of John Tyler 1841 - 1842 Priscilla Tyler (1816 - 1889), daughter-in-law of John Tyler 1842 - 1844 Julia Gardiner Tyler (1820 - 1889), wife of John Tyler 1844 -1845 Sarah Childress Polk (1803 - 1891), wife of James K. -

Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs: Educator, Artist, Author, Founder, and Civic Leader

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1994 Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs: Educator, Artist, Author, Founder, and Civic Leader Strong Carline Evone Williams Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Strong Carline Evone, "Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs: Educator, Artist, Author, Founder, and Civic Leader" (1994). Dissertations. 3477. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3477 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1994 Strong Carline Evone Williams LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO MARGARET TAYLOR GOSS BURROUGHS: EDUCATOR, ARTIST, AUTHOR, FOUNDER, AND CIVIC LEADER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND POLICY STUDIES BY CARLINE EVONE WILLIAMS STRONG CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 1994 Copyright by Carline Evone Williams Strong, 1994 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I began writing this dissertation, I was filled with feelings of vacillation and ambivalance. My directors, Dr. Steven Miller and Dr. Janis Fine, were instrumental in alleviating these concerns. Consequently, feelings of uncertanity were supplanted by encouragement, support and empathy. The professional expertise rendered by the other committee members Dr. Gerald Gutek and Dr. Joan Smith has been valued and appreciated. I want to acknowledge the unselfish support, through prayers and understanding, extended by my co-workers, friends and family.